My friendship with Leah Ke Yi Zheng (Instagram) started rather serendipitously. She was a stranger sitting next to me at a communal table inside Intelligentsia Coffee on East Randolph Street. I somehow initiated a conversation, and that was how we became friends, without knowing that we would soon both join the graduate program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; I would study art history and she, painting and drawing.

As a curator, I cherish a personal conversation with my artist friends in which we also chat about life––sometimes a bizarre dream from the night before or favorite foods from our hometowns. But in the grand scheme of things, art reflects our lives. Over the years, Leah has come to use Painting to pose a variety of formal and personal inquiries about objecthood, perception, and the nature of difference. Despite a transformation in styles and subjects, her paintings continue to mirror their maker’s personality: calm, contemplative, but uncompromising and fearless. Coinciding with Leah’s two-person show with David Hartt, Memory’s Great Vertigo at Paris London Hong Kong, this interview marks the first English-language coverage to spotlight the artist’s career. I hope it serves as an intimate frame, which crops the things she would like to show (and hide from) you into a distinct work of art.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Nicky Ni: I still remember the first time I saw your paintings. One of them reminded me of a still life by Chinese painter Chang Yu (1896–1966). How do you think your interests have matured over the years? How did graduate school help you paint, if it did at all?

Leah Ke Yi Zheng: Yes, those were my pre-SAIC paintings, back when I was a law school drop-out. It feels like a lifetime ago. I loved Chang Yu’s works for their reflection of literati painters’ interests, the reserved and complex emotions and sensibilities. I took a wandering path through a lot of experimentation and exploration in the beginning. Graduate school didn’t teach me how to paint, but it did strengthen my knowledge of Western artistic traditions and contemporary art. And I worked with Gaylen Gerber, which was essential. There was a period of time when I would do more intensive research on artists such as Fra Angelico, Francis Picabia, Rosemarie Trockel, Ad Reinhardt, Blinky Palermo, and Sherrie Levine. But now I’m taking a more instinctive approach, trying to find a balance between reading and looking, relying more on my perceptual acuity and other, more nebulous senses.

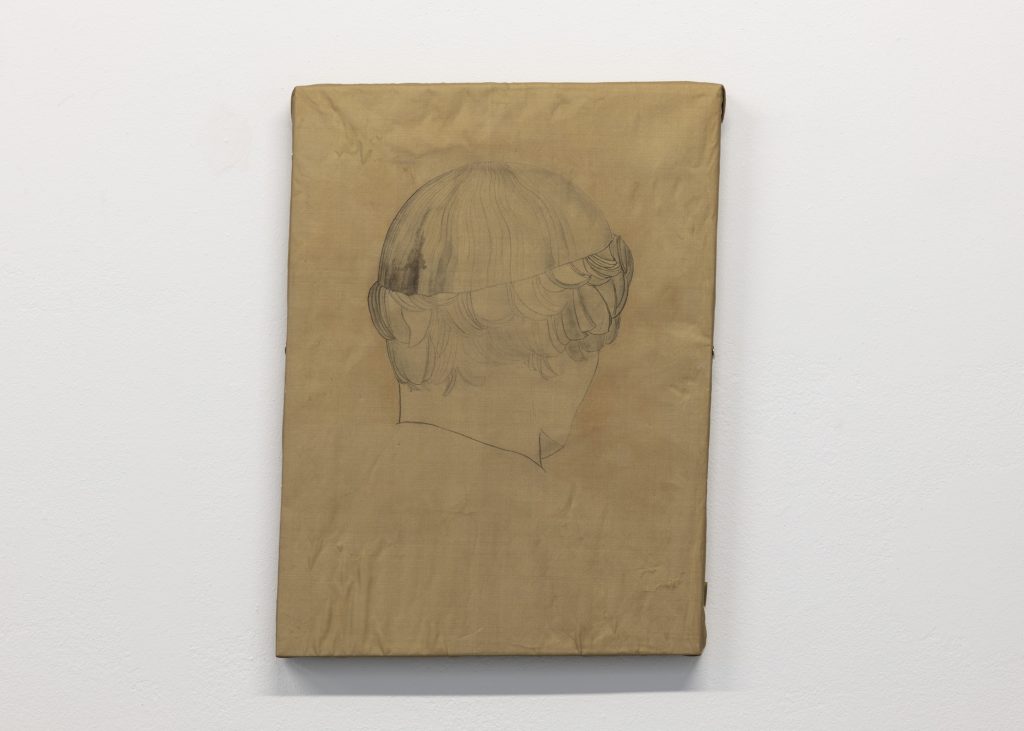

NN: Speaking of mentorship, I remember you mention your childhood art teacher and your early training in ink painting and calligraphy. I don’t want to reduce your more recent silk paintings to a product that comes out of this lineage of Chinese traditional paintings, but I do suspect that this background has nurtured your sensibility with materiality: lightness, translucency, folds, creases, and texture.

LKYZ: My childhood art teacher trained me in painting techniques and how to study ancient Chinese paintings. Our relationship was like an apprenticeship that lasted a long time—I studied with her from when I was four and a half years old until I left my hometown Wuyishan for college. We met frequently at her studio: in some years, three to four days a week; in other years, due to the heavy workload from school, just during the summer break. But it was a continuous thirteen years of dissecting images and building my own aesthetics.

My paintings branch off from the lineage of Chinese traditional paintings—it’s important for me to receive but also move beyond the influence of history. I use the same materials and techniques that a Chinese painter from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907 AD–960 AD) would use, but I turn the scroll painting and its flatness into an object. I have inherited a precision in hand movement from my childhood practices. And silk is a seemingly delicate but strong and finicky material; it feels like skin. This might be an exaggeration, but it is a bit like walking on a tightrope for me when I paint. That is not even important, I need to maintain a state where my intention, my mind and my hand can sync up and I can reach a place that has within it a sense of infinity. I’d also like to think of my paintings in relation to a fresco: my materials are water based, and when I paint, they’re absorbed into the fabric. It is very similar to how the paint is immersed into the wall of a fresco. And the whole wall becomes the painting.

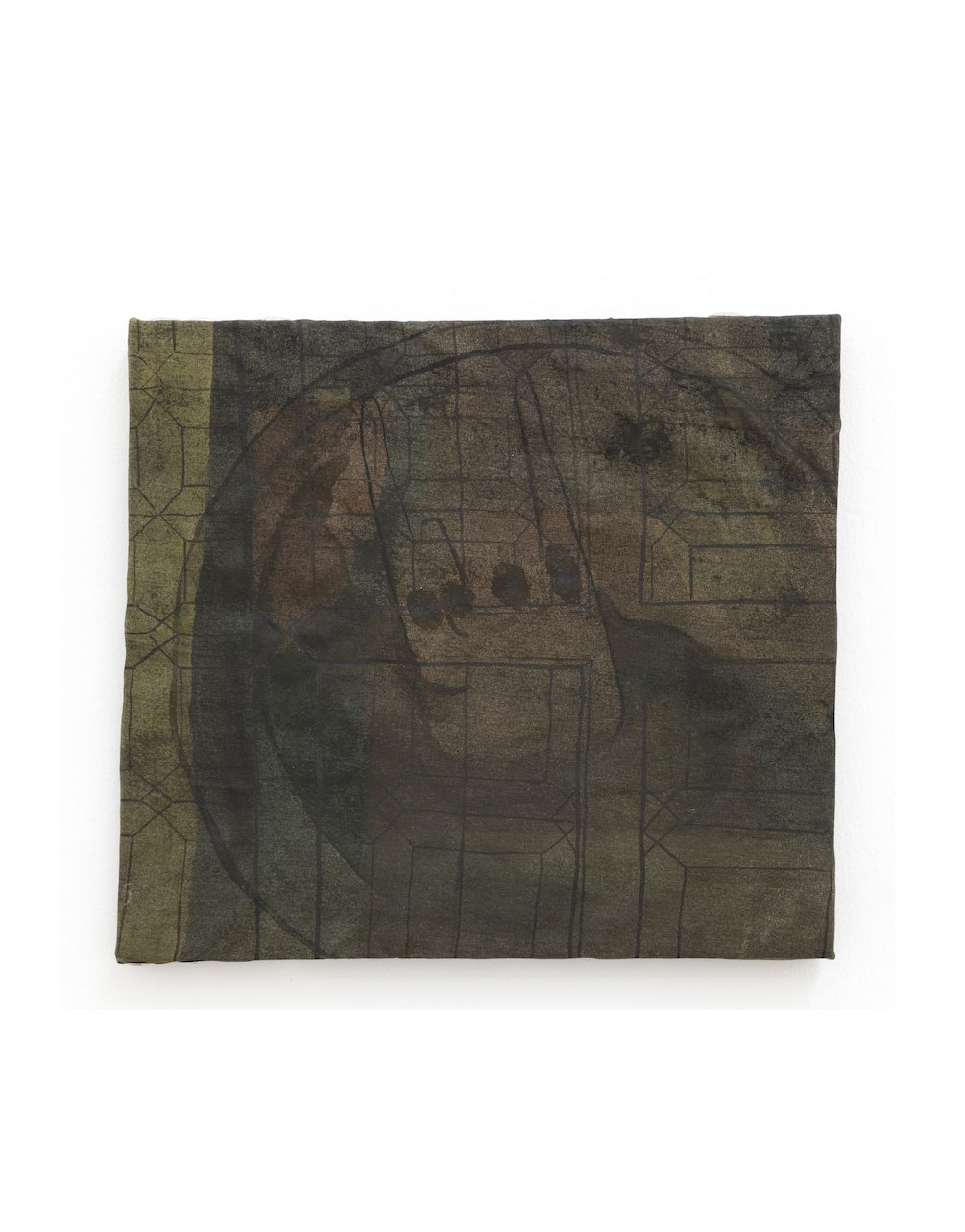

NN: I like how you mention fresco also as a way to negotiate the boundary of a painted surface, which is what I observe in your other body of work, the “Framework” series. I find it intriguing that you would use a CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine to make subtly oblique wood boards, the peripheries of which resemble an artist’s frame. You then apply paint directly onto these “wood sculptures.” How did these works come about?

LKYZ: Yes, I am very interested in the idea of “boundary” and try to approach it as a material to work with. Animals use various ways to set boundaries; people set boundaries to define a country, something to demarcate one thing from its surroundings; even an event has a temporal boundary. As Wittgenstein says, boundaries of our language are the boundaries of our world.

I started to conceptualize the “Framework” series when I visited the Frick Collection [in New York City]. I encountered a 13-century icon painting of Mary and Jesus done by a team of anonymous artists. It was an engaged framework––the painting and the frame are of the same piece of wood––and the piece as a whole touched me deeply. At the time, I started taking classes on using the CNC machine at SAIC. So I slowly developed this idea and made my first double-sided wood painting six months later. Both the “Frameworks” and the silk paintings are slightly oblique; they exemplify my attempt to destabilize the infrastructure of a painting, deviating just enough from the norm, but not enough to break the balance. And this balance is an uncanny one; it’s based on irregularities and aporia.

NN: Double-sidedness seems to be another primary focus of yours. You have hinged a painting perpendicularly onto the wall before, exposing both sides; however, most of the time, these double-sided wall pieces are conventionally hung, with one side shown and the other hidden. Also with the translucent silk material, you flirt with what is seen and what is known but only imagined, like a door ajar. What’s this fascination with having something hidden?

LKYZ: I like how you describe it as a door ajar. There is a psychological darkness to the nature of double-sidedness: we all have to work with absence. It’s like a two-headed snake, two bodies in one, two complete totalities, a multiplicity. But there is a barrier that prevents you from seeing both sides at once. My double-sided works are intended to live with this absence and challenge the viewer to embrace the frustration that this barrier causes. I hope my works can carve out a quiet and private space for the viewers to look and imagine, and make space for independent thinking, as our contemporary lives are so saturated with other people’s ideas and influences. I value the private moment in which one can truly be oneself.

NN: Your works currently on view at Paris London Hong Kong continue to investigate the intimacy of looking, through their more modest scale and further abstraction. How do you feel about this exhibition?

LKYZ: I was very excited when Jason Pickleman invited me to show my four paintings alongside David Hartt’s diptych. Small paintings are delicate and private expressions; I like to make small paintings for their uninterrupted process of making. It’s like fixing a watch, done with a complete understanding of the object. The wrist and hand movements can be very precise. And this precision emphasizes the magnitude of small decisions and details. Jason Pickleman, the curator of the show, describes the show as a “mind closet,” which I really appreciate.

NN: I also enjoyed the show greatly. Thank you so much for sharing your stories and allowing us to peek at what’s behind the enchanting and absorbing works of yours!

Leah Ke Yi Zheng’s work is on view through April 10th in Memory’s Great Vertigo with the work of David Hartt at Paris London Hong Kong in Chicago. Make an appointment here.

Featured Image: Leah Ke Yi Zheng pictured seated on a chair in a studio space with hung paintings, works in progress, and paint-splattered floors. Photo by Danny Bredar.

Nicky Ni is a curator and writer based in Chicago. She was co-founder of LITHIUM (2017-19), a Pilsen-based gallery dedicated to time-based art. LITHIUM then became TNL (aka. The Neu Lithium, Facebook/Instagram), an online editorial and curatorial platform for time-based and media art. Additionally, she has curated exhibitions or screenings at Conversations at the Edge, Mana Contemporary (Chicago), Museum of Contemporary Photography, SITE Galleries, among others. Photo by: Guanyu Xu.