There’s this thing that happens sometimes when I close my eyes and focus on nothing. It’s not like the after-image that you often get when looking at an object for a long time, but something else entirely. I see daubs of light, tiny flecks of indiscernible colors that move and dance in the darkness. And frequently, there is an actual place, a room that has no apparent walls, but feels like I’m somewhere else than where I really am–an astral projection of a space for safety and reflection. This place, I believe, was made manifest when I entered the main gallery this summer at the Hyde Park Art Center (HPAC) to view Folayemi Wilson’s latest work Dark Matter: Celestial Objects as Messengers of Love in These Troubled Times.

I met Fo late last year during my stint in the Teaching Artist’s studio of HPAC. I had worked there since September 2016, and was encouraged to apply to be a resident. A couple months later, I was sharing the space with another teaching artist. Now, mind you, I am an illustrator and graphic designer, so much of my work is done digitally, and here I was, occupying this HUGE studio, mostly by myself, because my studio mate was rarely there. I often pondered about my place in such a space, at such an institution, and what it really looked like for me to be an “artist” there. Open studio days really consisted of me opening the doors and showing people my work on Instagram. I didn’t exactly feel like I belonged there because the work I was doing was digital, taking up space, ergo, unconventional.

I went into Fo’s studio during a Super Sunday, an open studio day where the public can come meet the artists. I walked in sheepishly, as I had read her bio outside her door a little while beforehand while walking by after work one day: “Artists Fo Wilson (Folayemi) fashions ceramic vessels and other slip-cast objects with various materials to create a fanciful environment using abstract furniture forms and audio to create a dynamic, celestial Afro-futuristic landscape.” I was completely enthralled with a tinge of intimidation. This is a REAL artist doing REAL work, I thought. I listened as she spoke to a patron about her work and her process: how she created her objects in a sink factory, how she glazed them and put them in a kiln, how she was doing this all under the cover of night. Unconventional. No paintbrush or canvas in sight like the stereotypical artist. A maker. A builder. Suddenly I didn’t feel like what I was doing was so weird, and I remembered, I could create whatever I wanted in the space I was occupying. I didn’t need to have giant canvases and 3-dimensional objects to be an artist. What was important, what was relevant to me, was the work. Simply occupying space was the work I was supposed to be doing there.

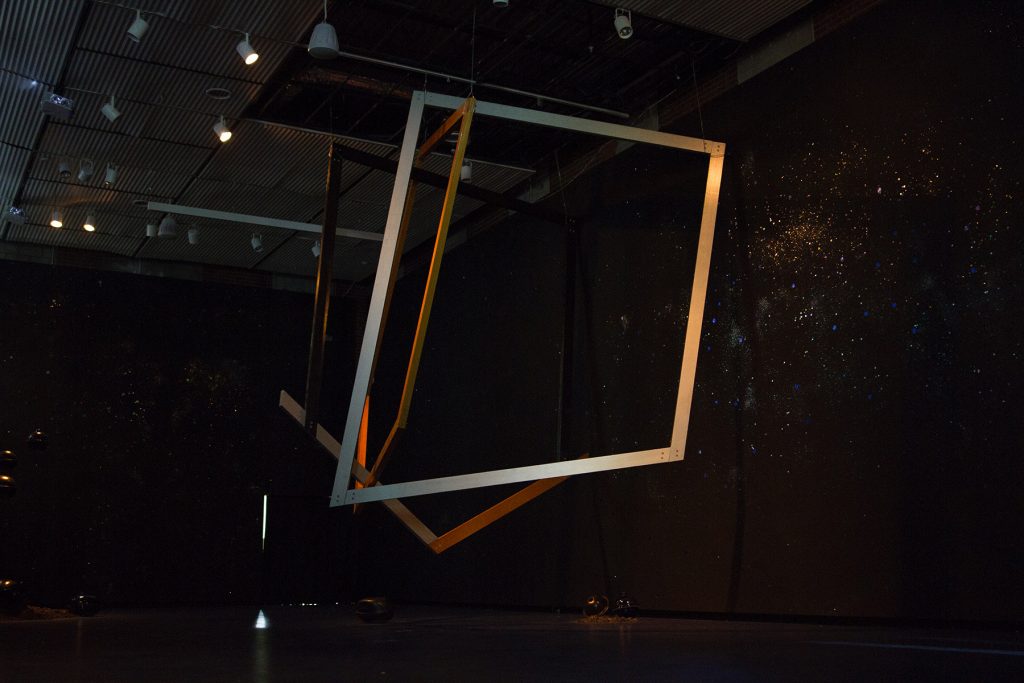

As I was prepping for a class or going to and fro, I snuck peeks here and there at Fo’s piece Dark Matter: Celestial Objects as Messengers of Love in These Troubled Times while it was being installed. The main gallery, which is an expansive 2,400 square feet and also possesses a catwalk, was transformed from walls of stark white to ones that were pitch black. The large windows that rest alongside the catwalk were covered with projection screens that showed NASA images of the sun and lunar surfaces. The floor was painted a deep shade of blue, creating a tension of sea meeting sky. And the glitter—the GLITTER!—with small hand-cut circles of clear film bursting through the darkness in flecks of iridescent color like stars. Ephemeral. Effective. And that was without the actual sculpted objects.

As the days went on, I watched the objects go in as well: glazed blue spheres in various sizes. Some hung low from the ceiling while others looked as though they had crash landed, begging the viewer to interact, all looking pregnant with information or gifts from across the sea of stars. The final pieces were the wooden frames hanging from the ceiling, representing the structure of the shotgun house, a style of house from West Africa occupied by African Americans after the Civil War in the American South, a reminder of a space many Black Americans occupied during the American Slave Trade and still occupy today.

For me, it invoked the theme of home, the place where we as humans belong. Home is a house, but it is also Earth, but is also the Universe. Home is safety and security. I believe Fo asks us, “If we don’t feel at home here in these troubled times, is space the next place for Black people to find comfort?” Of course Fo is not the first to ask this question, as Sun Ra, Ellen Gallagher and the writers she named the shotgun structure after, Zora Neale Hurston and Octavia Butler have asked it before. The exploration of space being the new frontier for Black Americans to experience home and safety from harm has been investigated across art platforms, but unlike other investigators of this topic, Fo brings these concepts down to Earth, in a physical space, where a community can explore these concepts together. Or, if they’re as lucky as I was, sneak in and be at peace by themselves. There were guided events like sound recordings, meditation workshops and a sound bath. I attended the meditation and sound bath event, and it was exactly what I expected, a still moment in a place that lent itself to peace and reflection. Instead of feeling like a gaping open space, it felt enclosed and warm. A safe space. A home.

When they finally dismantled the exhibit at the end of July, everyone who worked at HPAC was sad to see it go. We reflected often on how it made us feel and how the transformation of the space felt. There were so many stolen moments for quiet or contemplation. It was a welcoming place to hide in the midst of chaos. HPAC can get very busy during the summer, so it was a place to hide when I needed a breath. I personally was very sad to see it go, but what I was left with was a rush of inspiration. I had a moment when I stood in that room and thought about the ways I could transform a space to make people feel what I felt about my place in the world. A gallery always makes more sense to me when people are guided into an experience as opposed to eggshell colored walls and canvases. How could I make people feel at home in my work? How can I change their hearts to remember the sacredness of a place they’ve only visited once? Fo’s work left a profound impression on my own ideas about art in a space and how to have a wordless conversation about my identity with the people experiencing it.

Now when I close my eyes to see a safe space, I can see the gallery at the place I work, dark and transfigured. Not just a place of rumination but of revelation. Just like outer space, intangible and distant, but also a place of dreams.

Featured image: Installation view of “Dark Matter: Celestial Objects as Messengers of Love in These Troubled Times” by Folayemi Wilson at the Hyde Park Art Center. Catwalk with rotating NASA videos of the sun and moon. Photo by Michael Sullivan.

Teshika Silver is a freelance illustrator, designer, teaching artist and spiritual cultural worker spending time and living freely in Little Village, Chicago. Follow her work on Instagram @astratesh.