This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago Now, an initiative funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art that amplifies the voices of Chicago’s diverse creatives, past and present, and explores the essential role they play in shaping the now. The following interview followed a talk by Lori Waxman on June 10, 2022, presented by Red Line Service, an organization that creates cultural programming by and for Chicagoans with a lived experience of homelessness.

There is an intrinsic value in the written word; newspapers and books project an authority that other forms of media don’t have. Published reviews that interpret and critique visual culture draw attention to art, artists, galleries, and museums. That media coverage provides a certain validation for the artist or institution who is then in turn able to create and show more work. With her project “60 wrd/min art critic”, Chicago art critic, historian, and professor Lori Waxman shows us how the niche relationship between artist and critic can be used to bolster social ties in the greater community outside of the insular art world. At Weinberg/Newton Gallery in partnership with Art Design Chicago and Red Line Service, Waxman delivered a lecture contextualizing her project by defining social art and showing us how artists over the years have used their art to engage with society and specific communities.

Jen Torwudzo-Stroh: In your own words, tell us about your project “60 word/min art critic”.

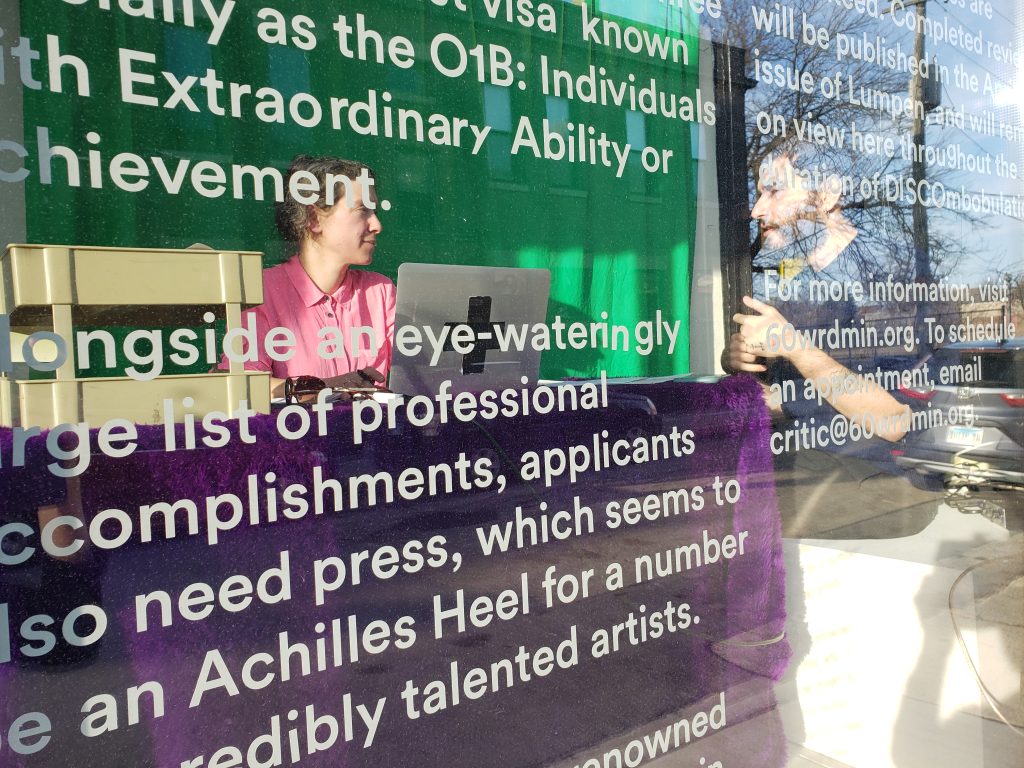

Lori Waxman: In its basic general format, I go to a town with an art scene that is not on the national or international art map [unlike cities like New York or London]. There, I set up shop in an art space that hosts me for three days, and I write around 10 reviews a day. I write a review for anybody locally who wants one, space and time permitting. The only prerequisite I have is that, if somebody wants a review, they must be okay with participating in the public aspect of the performance. In exchange, they get a formal, thoughtful review. All of these reviews are then published after the fact in a local publication.

The public aspect of the performance is that my space is open to the public while I’m writing the reviews. I may be in a storefront window, so it can be very public. In addition, the computer that I’m typing on is hooked up to a screen monitor or projector so that the writing process itself is visible in real-time, making the process itself public in a way that writing normally isn’t.

JTS: What part of the project do you consider art? Is it the process, the product, or both?

LW: It’s very much a hybrid, as a whole. If I were to break it down, I would say the artsier aspects of it are in the performance. It’s performative art, it’s the theatricalization of art criticism. I’m making it public by doing it on a stage.

By art criticism, I mean the writing as well as the person, the art critic. What do they look like? What are they doing when they’re performing art criticism? What does that process look like? The art criticism part is the actual piece of writing, it’s the formal critical thinking and writing.

JTS: Did you consider yourself an artist before this project?

LW: I don’t consider myself an artist. I’m an art critic and historian who is doing a project that’s a little out there. It’s a hybrid project, so it involves identities that are not really my own. I write, which is creative, but it’s not visual art. I’m not a creative writer. I only write art history.

JTS: Do you see criticism as a creative outlet for you?

LW: Oh, I do for sure! But I’m an art critic specifically—visual art and the creative aspect of what I do are not comparable. It’s a totally other thing. I think there is a creative aspect to what I do, but it’s not the dominant quality, nor the dominant purpose of it. To a greater or lesser extent, my writing is satisfying to me as a creative endeavor—but not entirely. Critical art writing is quite specific and purposeful, and it’s a critical act more than a creative act. But I think when that’s done well it has aspects of creativity involved. For me, I think it’s more of a critical release, the completion of thought. I realize that the only way I have to complete thoughts about art is if I write about it.

JTS: How does that reflect in this project?

LW: It doesn’t. This performance project is a thing unto itself. In many ways, it’s the opposite of my regular acts of criticism because I don’t choose what I’m writing about. And I have a different responsibility that I feel toward the artist participants. It just feels like an entirely different agreement and has a very different purpose.

JTS: What inspired you to do this project?

LW: I’ve been doing these since 2005. The inspiration was from my day job at the time, which I loved. I worked in publishing at Distributed Art Publishers, which was an amazing art book publishing and distribution house in New York. My job was two-part: I was the managing editor for our small roster of publications, and I wrote all of our catalog copy. This was back in the day when they printed the catalog in addition to having it online. I wrote all the catalog copy for all of these books, many of which did not even exist yet. They ranged from a few words to 400 words in length, and I got really good at doing them. I took a lot of pride in making them, and I developed a certain skill set for brief, art-related writing that was also not total BS.

I was doing that and at the same time I was freelance art reviewing, trying to make it as an art critic. My boyfriend, who I’m now married to, was an emerging artist at the time. All of his friends were emerging artists, some had just gotten their MFAs, and they were like, “How do we get reviews? What is this weird opaque process that is so important to making it [as an artist]?”

So I had this idea—what if I flip the system? What if I just write reviews for anybody who wants one, but they’re shorter? It was a total experiment—it was never meant to be a long-term thing. I lived in New York at the time and that’s where I did it. I later moved to Chicago and I did it again at a Mess Hall in Rogers Park, a space that doesn’t exist anymore but was important at the time. Then, someone who had been involved with Mess Hall and had moved back home to Knoxville, Tennessee heard about the project and called me up out of the blue. They said, “I have an idea, what if you came and did it in Knoxville? We have a lot of artists, but we don’t even have an art critic.”

I said, “OK! Sure?” We did it in a storefront space that he was running and it was mind-blowing. People were lined up out the door to get a review. They wanted one so badly, because there was no feedback whatsoever. There were super devoted artists at all skill levels—people who have been working in their backyards for 20 years. It was wild.

JTS: The project has existed in many iterations over time. How does that context change how you work?

LW: It doesn’t really change how I work. The two things I think are very critical elements of the performance is being in an off-the-grid place regarding the art world and the transparency of the writing process, projecting the writing somehow. It’s way more interesting in off-the-grid places. I do it where it makes sense in terms of trying to reach beyond the system where there are needs not being met by practicing artists. The project has a certain register that it can only have in such places.

JTS: Do you still get editorial gratification out of this project?

LW: Yes, absolutely. It’s kind of wild. It doesn’t happen very often in my regular job as a critic—I don’t get a lot of feedback. But my writing process is very immediate when I’m doing it as part of the performance.

It keeps me on my toes, but it’s very sensitive because you’re really dealing with human beings, you’re giving them feedback. People have all kinds of reasons for making art, especially when they’re not making it as a professional in a big city. One time, these parents brought in their son who has autism and who’s an abstract painter—and he’s a good abstract painter. He and his parents sort of sat there while I was writing. I took great care with it and then they read it afterwards in the space I was working. I’m watching and the mother starts to cry. They were tears of relief and appreciation of having their son’s work validated in a certain way. For me, as a person who has this skillset and the cultural credibility to do that, it’s mind blowing. That’s rare, but it’s happened a couple of times. All kinds of gratification can happen for me personally that just aren’t a part of my regular job as an art critic.

JTS: Why is social art important right now at this moment? Why did you choose to talk about social art in your lecture at Weinberg/Newton Gallery and why did we need to hear about it?

LW: It’s a crossing point between what Red Line Service is doing and what I’m doing in this project. Social art is a very important art form today, so it made sense to try and give a little bit of history on it. More generally, I would say [I chose to talk about social art] because we live in an increasingly digitized world and nobody actually socializes. We have lost so many social aspects of everyday life, so it has become something symbolic or something with symbolic potential. What else is art making than harnessing the symbolic potential of color and form?

There is no humanism for art criticism to harness—there never was. It has not ever been that kind of thing. I’m doing an experiment that I think fits with this larger movement toward understanding social relations as something increasingly bereft in daily life. There’s something for artists to work with suddenly because they’ve lost the meaning they’ve always had. It’s not so much a direct correlation to harnessing something that has been lost from art criticism, but doing what I do as an art critic and noticing that a certain amount of socializing is just missing, period. I can make some interesting use of that. I can bring that in.

The desire to engage with society is something that is innate in us. Whether we’re doctors, chefs, or teachers, those of us who are driven by a desire to contribute to society will find a way to do it regardless of our profession or skills. Covid-19 has amplified our need to connect; presented with unprecedented turmoil and sudden isolation, many of us asked how we can contribute to and connect with our community. Social art is made for moments like this because it reminds us that we’re all connected in some way.

About the Author: Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is an arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago, IL.

About the Illustrator: Kiki Lechuga-Dupont is a multidisciplinary artist based in Evanston, Illinois. She’s inspired by visual memory and its capacity for emotion and perspective. Though her body of work ranges in subject matter and style, she strives to design pieces that evoke a sense of wonder and mindfulness. When she’s not working, she’s tasting teas, collecting cookbooks, and exploring new drawing techniques. Photo by Matt Austin.