“All art is quite useless.”—Oscar Wilde

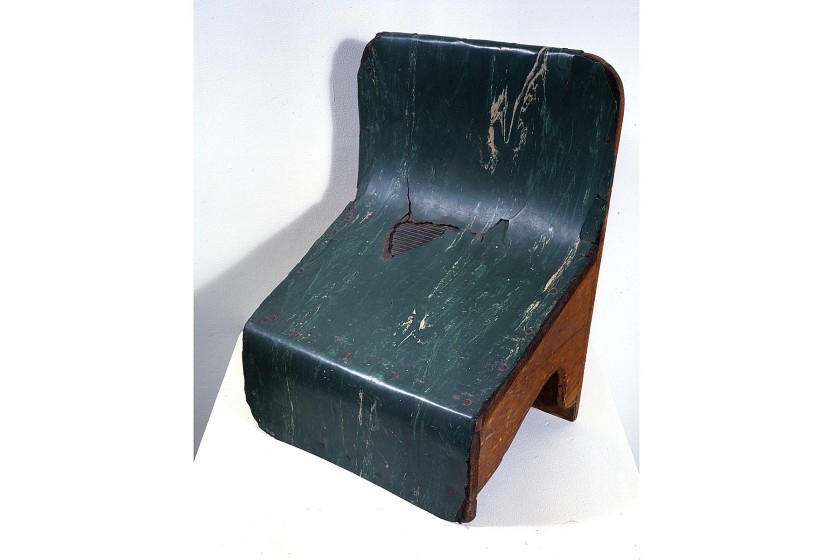

You can’t really step on a slanted step. The Slant Step’s so-called “step” inclines at a 45 degree angle, too steep for a foothold. It is an object that teases utility, like Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined tea-cup, or Marcel Duchamp’s inverted urinal. What is it for? Nobody could figure that out, and that’s the point. It is an inside joke: a found object whose elusive purpose made for a compelling and enduring art mystery. It is an invitation, a riddle, a call for response.

As legend goes, William T. Wiley found the Slant Step in a San Francisco thrift shop for fifty cents in the Sixties and bought it as a gift for his student—the artist Bruce Nauman, who went on to cast molds in homage. With time it became an object of fixation for a funk art movement of Bay Area artists and poets, culminating in a group show, The Slant Step Show, at Berkeley Gallery in 1966. When Richard Serra stole the Slant Step from that show and brought it to New York, this wayward object transcended its purely regional interest to art historians (file under: Dada, ready-made, defamiliarization, irreverent art).

/

I can’t place when or where I first learned of the Slant Step, but conceptual minimalist artist Gordon Hall’s book OVER-BELIEFS led me back to it. Oh right—that thing, I think. I feel myself pulled back into its magnetic field. Is this blood memory, my sense of unearned familiarity with an object I have never seen in person? I find out about a new edition of the long out-of-print Slant Step Book, published by Verge Art Center, with a companion book teasing out its slanted line of influence on contemporary artists. I chase down a review copy from the publisher.

Turn to page one. Turns out I’m not the only one who remembers it as “that thing”:

Interviewer: What’s the name of that store again?

Nauman: The Mount Carmel Salvage Shop, on Lovell St.

Interviewer: How long ago was that, that you guys found that thing?

The Slant Step doesn’t go by name until a page later. Instead, it is addressed by its place of origin; or at least, where it was found. I count four instances of the demonstrative “that.” “That” is deictic; its frame of reference is context-dependent. Deictics can be a convenient class of words: relative, condensed, and flexible. But they are also prone to ambiguity. As a place-holder word, “that” is open enough to net in anything, but loose enough that it might slip back out again. So, what is “that thing” we’re describing? It is “so ambiguous as to be infinitely suggestive,” Artforum wrote after the group show.

/

Ambiguity is my jam. I swarm towards irresolvability; the blur and whirr of a nonbinary politics. Down with “either/or,” up with “both/and.” Ambiguity is ambidextrous: on the one hand, and on the other. It’s (at least) double sense, refusing to resolve one way or another. Not to be mistaken for vagueness; ambiguity makes room for specificity but wavers beyond decidability, so that one must hold its multiple possibilities at once.

Gordon Hall’s essay for Verge’s book draws out a queer politics of slow reading, delayed assumptions in the name of avoided identification. “It makes me want to see it as more than one thing at once, or as many different things in quick succession. Looking to the Slant Step as a teacher, I want to learn what it seems to already know—I can’t always know what I am looking at.” In the polyvalence of the Slant Step, Hall finds resonance with transgender rights, including the legislative hullabaloo around inclusive bathroom access.

The connections Hall draws between minimal sculpture and gender politics are in conversation with David Getsy’s book Abstract Bodies, a book which applies the lens of transgender studies to art history to attend to the shifting morphology of Sixties sculptures by non-transgender artists. Getsy approaches these objects with a trans* vocabulary of ambiguity, plurality, and non-fixedness, observing how “abstracted bodies facilitate capacities for seeing the human otherwise.”

/

Q: What do you do with an apparently useless object?

A: Learn from it.

For years, the Slant Step sat in the front of Frank Owen’s classroom at Sacramento State as a model for students to draw from. Pedagogic usefulness of uselessness (try that for a koan).

Another Gordon Hall essay “Object Lessons” outlines an inquisitive approach to objects: “What is this object trying to teach me?” or, as they rephrase their own question, “What does this object-body want my flesh-body to understand as a result of our encounter?”

/

When I went to the opening for Hall’s solo show Uselessness at Document, the first sculpture I saw through the crowded door was a small coral pink box. Aha, a tool box! I thought. But wait, why am I so hasty to call this a “tool box”? Tools, by definition useful, would be out of place in an exhibit of uselessness. Less useful is an art object that looks like a box but is in fact empty and just for show.

[ All shell and surface ] [ filling up three-dimensional space ] [ 12 x 18 x 11 inches ] [ not unlike Warhol’s Brillo boxes ]. I came closer. Tried to empty my preconceptions. Slow down my reading. Okay. Close reading of Closed Box with Painted Top. The sculpture’s lid is “closed.” Does it come off? Could there be something stuffed inside, contained or hidden away? Maybe we call it a “tool box” anyway, a tool box of or for uselessness. What are the conceptual tools of uselessness?

/

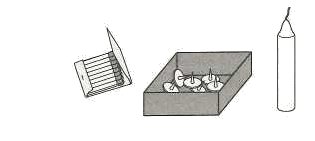

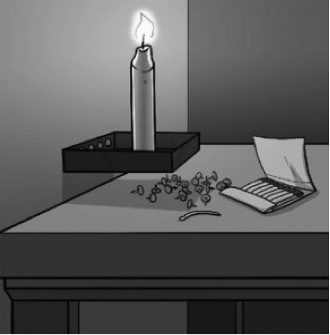

Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias in how we apprehend objects only according to their “intended” use. Let’s say I give you a box of tacks and a candle: can you attach the candle to the wall without dripping wax?

When the psychologist Karl Duncker posed the so-called Candle Problem, only a minority of his experiment participants recognized the potential of the box which was holding the tacks as a makeshift candleholder. Over-literal usage: most participants could not mentally separate the box of tacks = a box + tacks.

But of course, that is a rather limited example. The box still has the same verb (holding). There are so many other ways an object can be hacked or creatively abused for other purposes. Break out of the box: how many alternative uses can you come up with for that box?

/

Near Closed Box with Painted Top is another deceptively useful/useless sculpture: Shim (White). Shim! A name that shimmies, that shimmers, halfway between “she” and “him.” So much imagination in a name for a tool with a pedestrian purpose: a shim is a thin tapered surface for leveling and transportation. Hall’s slanted sculpture draws attention to the manual labor of art transportation and installation, especially in proximity to the pink seeming-toolbox. Stains (orange-red splotches, “spills” interrupting white monochrome) verge on telling histories of such potential use. Carrying things around can be useful. Is the business of making, transporting, displaying, and/or selling art objects “useful”?

/

The annals of the Slant Step’s zigzag history of usage. Not just generating knock-off tributes, but also speculative functions:

- “Probably an old shoe shine stand,” William T. Wiley mused. Fifty years later, Terry Berlier’s drawing Interruption (2019) sketches out this possibility, a tied shoe hovering above two Slant Steps.

- Bruce Naumann used it as a footrest as he slouched in his chair. “It’s perfect. You can put your feet on Slant Step and then you can lean back in the chair.”

- Aay Preston-Myint’s mixed media response makes a glory hole out of the Slant Step. His title doubles as artist statement—Initial Notes on Slant Step: 1. Slant Step slipping into the black (glory)hole of its own spotlight 2. An object with dubious purpose and provenance can only/always be a pervertible (2019)

- Angela Willets’ response Artist’s Body-based Research: Slant Step as Mirror (2019) reimagines the Slant Step as a multi-surface vanity.

- The organizer of the Slant Step Show, a poet named William Witherup, declared it was meant to be a squatty potty.

A psychologist would applaud these artists’ resourcefulness. Given the wide range of possibilities, I was disappointed to discover that the Slant Step’s original coterie seemed to agree upon (e) a squatty potty as the probable usage. I want to flush this hypothesis out of my mind. Why should the Slant Step be “fixed” within a framework of functionality? To dwell in resourceful usefulness is not the same as to admire uselessness. What I relish about the Slant Step is its strangeness, its irreducibility. I don’t want to insist on making use of it.

/

Unproductivity has a sexual overtone to it. Consider Ross Gay’s essay Loitering Is Delightful: “Loitering, as you know, means fucking off, or doing jack shit, or jacking off, and given that two of those three terms have sexual connotations, it’s no great imaginative leap to know that it is a repressed and repressive (sexual and otherwise) culture, at least, that invented and criminalized the concept.”

The work in Uselessness is unquestionably erotic in charge. In their book Over-Beliefs, Hall acknowledges and foregrounds this dimension of their art: “There is also an erotics in the way that I (and the viewer, I hope) relate to the objects—a bodily relationship that aims to produce intimate, hard-to-recognize body feelings. I came to sculpture through being a dancer, and so I make the objects with my body and then figure out what to do with them using my own and other people’s bodies.”

To my mind, the most overtly sexual sculpture in the exhibit is Turned Hanging Bar (Beige). A lesson in orientation: inverting can be a mode of perverting, as Duchamp’s readymade Fountain taught the art world. This upside down hanging-bar, if we are to take the title at face value, is a visual abberation as the only object in the room above my eye sight, and its bulbous ridges suggest anal beads.

Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology, reapproaching the “orientation” in sexual orientation: understanding perception of objects, as exposing their social relation to us as subjects. Ahmed points out the origin of “queer” from the Indo-European word for “twist,” as an inverted re-direction of sexual desire. A turn, a re-orientation away from the straight lines of compulsory heterosexuality.

/

Perhaps what I am trying to do here is to make a tower out of slant steps, scaling upwards but impossible to climb. Working against gravity, like crawling up a long slide. This is what essay-writing feels like so much of the time. Exertion. A struggle to attain clarity; to name my feelings. But so much of what I am trying to articulate feels out of reach.

I think it’s telling how low to the ground Gordon Hall’s exhibit is. I need to lower my vision. Verticality isn’t helpful right now. I’ll stop making stacks. There is too much I am trying to contain, but maybe the inevitable spill is more interesting. So I’ll try instead to think of horizontal relations: to constellate the objects, ideas, and feelings which are around and in me.

Scanning across the room, one sees sibling pieces calling out to each other. Object kinship. Most immediately apparent are the two Three-Part Stools, further identified as (Grey, White, Pink) and (Cream, Beige, Green). Both are miniature towers of three monochrome blocks, each lower rung successfully smaller so that when viewed from directly above, you can’t see the sublayers. They are approximately the same size and are similarly banged up, with slight punctures and scratches almost as if they were found objects. Textures that touch up, colors, heights, form: the makeup of this queer family. Each is still one-of-a-kind, but through their relatedness, they are not alone. This is a politics of care.

/

I love the parentheses in the sculpture titles, a careful and caring detail. The parenthetical subtitles call attention to the surface of the objects: the primacy of color or material. What they are made of, how they appear to the eye. For instance Three-Part Stool (Cream, Beige, Green) or Kneeling Object III (Poplar). An approach to nomenclature rooted in minimal, observational description. Oscillation between minor and major / a metonymic identifier like Oedipus’s swollen ankle / an entanglement of bodily part and name.

Parentheticals can easily be cast aside, but their curled frames also elevate its inner riches. The parenthetical steps foot in a room where it maybe wasn’t invited and casts a long shadow, shifting our understanding of what we previously attended to.

Coming back to our examples, function is still implied by names like “stool” or “kneeling”—but even these are defamiliarized. A “three-part stool” is at most one-third useful; less in a gallery context where one cannot sit on it. And “kneeling object” invokes a question of animacy: is the object kneeling or is it made for a user to kneel on? (If one were to kneel on it: what for, and how? What kind of knee play is invoked?)

/

I’m interested in how Bay Area’s Slant Step history touches up with Gordon Hall’s exhibit in Chicago. The particularity of regionalism and how it can hook up with expansiveness. So when I finish the Slant Step Book, I make a second trip back to Document.

Hall’s minimal sculptures interrogate the possibilities of form without function. All of the work in the exhibit reward sustained close attention and careful reading. Defamiliarized miniatures that border familiar identities. On first reading, I am so tempted to give in to the instinct to name and classify (tool box, water fountain basin), but Hall asks for a more generous, transformational way of viewing. Queering the way we see, embracing both their specificity and ambiguity.

Gordon Hall originally presented the sculptures shown in Uselessness within the suggestive context of performances at the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art. Deconstructing the show over Thai food next door, my friends expressed their disappointment that Document did not carry over these performances at the opening. On the other hand, however, I was drawn in by the mysteriousness of the objects and the suggestive potentiality of their unknown-to-me performance histories: the space this left for my imagination.

/

Here I sit on the floor, meditatively considering Sitting (Brick Object) (III).

A low stooped object, saddle-like. My mind rushes in two directions simultaneously: chimney, chair. Why not both = chimney chair. A visual portmanteau, two everyday objects defamiliarized by association. I’ve sat on roofs before, and I suppose on the roof a chimney could be a seat, though brick is not the most commodious surface for durational sitting. Now I am both inside and outside; I do not object. The porousness of perception: this brick object invites me to inhabit space differently.

My mind wanders associatively to various rooftops I have known and loved: memories of sneaking out through the window of my friend’s dorm room to the roof overlooking the police station parking lot… other rooftops around campus we weren’t supposed to be on but a friend with a copy of a janitorial key (nicknamed “Mr. Go”) provided illicit access to… another vine-ridden rooftop I hosted poetry readings on…

I’m interested in how Hall’s sculptures touch me, and how I touch them. Chiasmic entanglement of reciprocal touch as a “flesh” between us, to invoke Maurice Merleau-Ponty. I am provoked: I feel something stir in me, I feel my teeming undercurrents make contact with the cells around me. Tuning into what Kathleen Stewart calls “the resonance in things,” those “little worlds of identity and desire.” Encounter is a two-way street: in seeing up close, I am seen; in touching, I am touched.

/

Journalists regard with suspicion writers with a “slant.” I profess a secret admiration for slants. A slant angle dreams against the grain of the object, abandoning consideration of its original intent in favor of a willful creative re-reading which slopes towards more personal purposes. The logic of slant reading is asymptotic, working its way closer to the target but never quite brushing. The origin is unknown, unapproachable; instead, I plot my own desire line, which is at best a slant rhyme and at worst a misreading. Not an identification of the object, but an identification between the viewer and the viewed.

Eventually, close reading tilts toward “too-close reading,” a psychoanalytic deep end. To be sure: overinvestment might be a recipe for falling flat on one’s face. I risk making the art about me, which is useless to anyone else reading this art review. In trying to find personal closure through close reading, I don’t mean to close off the work’s other potentialities. I want my own sense of closeness to Hall’s work to open up additional pathways for an abundance of accretional meanings and responses, both useful and useless. Art is maximally charged, reaching out in generative ways for viewers to make what they will of it. This is, I suspect, the slanted crux of Hall’s OVER-BELIEFS —not to be “over” belief, but overly committed to the power of beliefs in shaping materiality.

Featured image: Installation view of Gordon Hall’s Chicago exhibit USELESSNESS, courtesy Document Gallery.

Noa/h Fields is a genderqueer poet and teaching artist. They have written for Filthy Dreams, Telekom Electronic Beats, Anomalous Press, and Scapi Magazine, among other publications. Their first poetry book WITH is out from Ghost City Press. They are fond of techno and avocados.