A good girl can fight her way through a thousand troops;

A good horse can gallop into a myriad-man battle!

—Wilt Idema, Heroines of Jiangyong: Chinese Narrative Ballads in Women’s Script (2008)

“你来人间一趟,你要看看太阳,和心爱的人,一起走在街上。”

你们谈着梦想,翻越山川海洋,彼此脸庞有光,眼睛闪闪发亮。

Writing is private. Writing in a foreign language is even more so. Hidden Letters, a 2022 documentary directed by Violet Du Feng and Qing Zhao, dives into a little-known cultural heritage unique to Jiang Yong, Hunan Province in China. Also called the “Ant Script,” Nüshu (女书, or literally “women’s script”) is an exclusive writing system only learned, used, and taught among women.

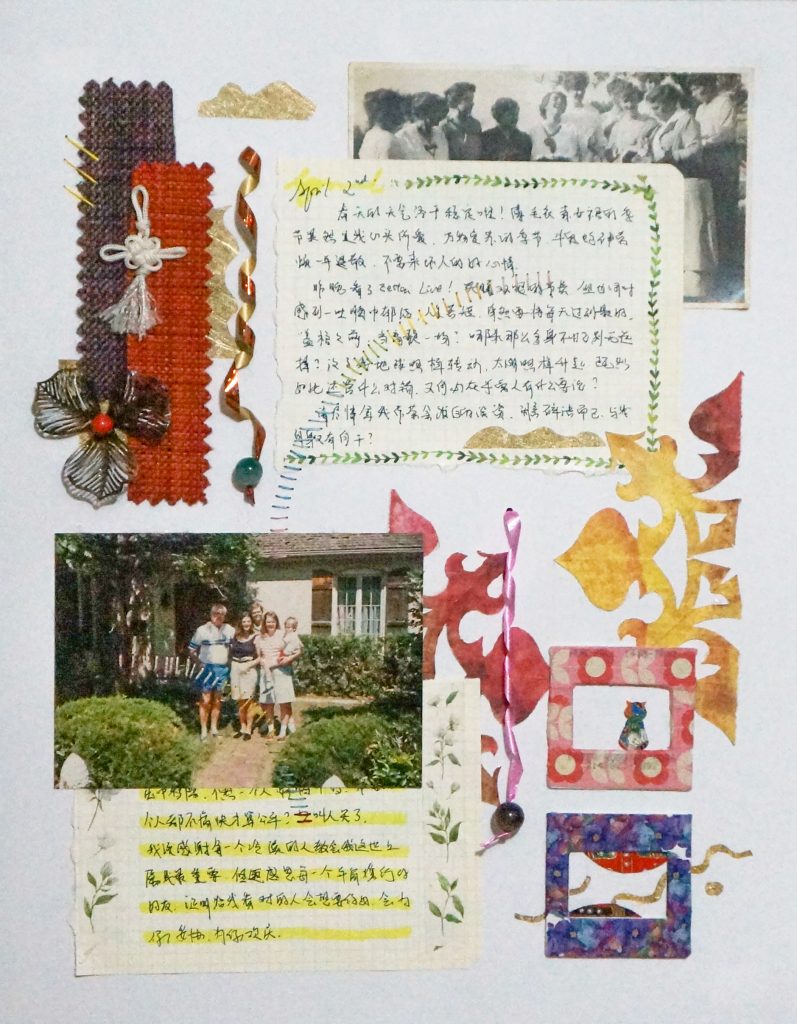

In the movie, two Chinese women embraced Nüshu culture in dramatically different ways, though stimulated by similar sentiments and resolutions. Hu Xin, one of the youngest nationally-recognized Nüshu inheritors, studied and practiced Nüshu in an attempt to preserve its original value as women’s private conversations with themselves and their “sisters,” but she finds the commercialization of Nüshu, though necessary, is troublesome because the essence of privacy, intimacy, and female perseverance gets lost in the mass production process. Meanwhile, Simu, a forwarding Shanghai performer and artist who incorporates Nüshu characters and poetry into her calligraphy and music, boldly merges contemporary feminism concepts, her personal journey as a woman artist in China, and her hopes for Chinese women’s future with Nüshu’s historic functionality as an exclusive communication system for women to connect with themselves while fostering a universal sisterhood.

Early research often forced a negative connotation upon Nüshu, considering the scripture a secret language that a revolutionary group used to overthrow China’s male authority; others regarded Nüshu as a tragic tombstone of generations of women who powerlessly withered into nothingness due to oppression and silencing. However, Nüshu writers were neither powerless and passive victims nor ambitious revolutionaries. While the system intended to objectify them by depriving them of all basic rights, keeping them at home like caged birds, and reducing their value to nothing but being a good wife and bearing children, these women maintained their independence and personality. They created a safe space to vent their pain and fear, validate their emotions, and discover their true selves while supporting each other throughout the arduous journey.

While Nüshu culture rarely prevails beyond its hometown, its essence as a language for the self has always been practiced by countless Chinese women, especially those residing in foreign countries. Even if two Nüshu users have never met, the shared script can serve as the tightest bond between the two souls.

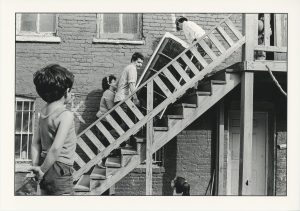

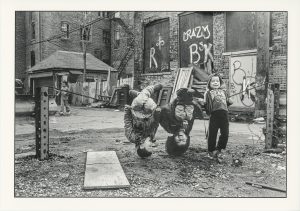

It is never easy to be a foreigner in the United States, let alone a Chinese woman artist in Kansas and Missouri. When people asked how life in China was, I often suggested that they “deduct ten years of technological and cultural progress from the United States.” What I didn’t mention was, ironically, that I’d applied the same time degradation to my time in Missouri and Kansas. These two states are indeed making progress in understanding the cultural diversity in communities, yet this progress is more scattered, slow, and superficial compared to other cities even within the midwest region, such as Chicago and Naperville. The mid-’60s stereotype where Asians were considered the model minority and treated with envy and scrutiny remains prevailing in the heartland. Asian women are still objectified as sexual icons (think the Dragon Lady) and are expected to be docile, obedient, and exotic. My black hair and yellow skin were enough for most to establish the expectation of someone smart, non-political, invisible, but hard-working. My classic look had brought me many advantages and kindness, but it was the same kindness that someone would give to their beloved pet or a parent’s adoration of their child when the kid tried to do something beyond their age, with a serious look, pretending to be an adult.

My voice mattered, but not in the same way others’ voices did. Suddenly, I remembered what another exchange student from my Shanghai college said during my first year at Washburn University: “This is not the America I wanted.”

来美国那么多年了,现实与理想仍然无法吻合。或许,成长过程中憧憬向往的那世界本就与现实不符。我曾想过,只要来到这个国度便能获得一直想要的尊重与自由。但其实并然。原来不论在哪里都会存在根深蒂固和食古不化的人,但在哪里也都会存在不甘愿就这样沉默下去的人。很多时候与人说着说着,我会清晰地感觉到对方逐渐变得漫不经心。他们的眼神飘忽、笑容敷衍,却还是维持着教科书般的礼貌。于是我学会了恰到好处地结束我们的对话,微笑、告别。如今的我能够坦然接收自己奉寻之理罕被彻底理解接收的现实,也能够在于理想颇有落差的现实之中寻找升华的可能。我永远都将是个外来者。是以与其与面红耳赤地矫正他人对自的认知,不如便这样抱元守一,走好自己的路。

“Then, why not turn to your own?” you might ask. However, while this collective mentality can be financially and professionally beneficial, it is often insufficient as an emotional support for Chinese women. Like the warm-hearted yet largely conservative rural population in the Midwest, the Chinese population shares similar characteristics while preserving other traits stemming from traditional Chinese gender expectations. The older Chinese men I turned to for guidance would give me fatherly advice based on how they believed a girl should behave. Meanwhile, my fellow females had more than once suggested that I should take sexual comments “as a compliment.” “Let the men look!” they said as they suggested to me: “Just settle down.” My outspokenness was to them “stirring up troubles” and not girl-like. Even my effort to spread cultural heritage in a fashion more relevant to what was going on in the community was greeted with indifference and dismissal—“Why bother explaining?” “Don’t be so serious.” I found myself stuck in a paradox: my lack of connection to a community urged me to continually reach out to other Chinese people in the area, especially Chinese women, whereas the responses I got were consistently oppressive, albeit spoken in a genuine, kind, and caring tone. The native Midwesterners only aggravated my sense of isolation. The local community functioned as a temporary emotional and cultural shelter yet failed to suffice my need for connection and support.

On the other hand, many Chinese women I know in the Midwest have internalized the classic Chinese gender stereotypes that a woman’s highest value is a good daughter, a submissive wife, and a sacrificial mother. Even for individuals who have stepped out of the domestic expectation and chosen to pursue professional development, compared to those I encountered in other parts of the United States, Chinese women in the Midwest tend to choose a career that glorifies their ancestry, such as business, medicine, law, etc. This subconscious internalization of racism has induced a mechanism of minimizing, devaluing, and denigrating one’s cultural heritage. Though it frequently operates without any awareness or intention of harm, internalizing racism, regardless, leads to intra-ethnic othering, self-depreciation, and corroborating existing systems of oppression.

I had exhausted my wits.

但如果能够那么轻而易举地就成长,人生也就不能称之为人生啦。怨恨着,后悔着,在黑夜深处抱着被子缩成一团嚎啕大哭的你真的很棒呀。为什么要在他人的眼中寻找自己的影子,镜子里的你虽然苍白虚弱,但也仍在努力地微笑着不是吗?要为自己感到骄傲啊。你无助地问着,到底还需要多久才会好起来,却又温柔地告诉某个人你可以给予你所有的时间,直到世界尽头。既然如此,为什么不将那样的体贴和包容也送给自己?你配得上所有最好的,就算现在不相信,也请不要忘记呀。

那些在无数个夜晚辗转反侧立下的誓言、那些用稚嫩声音嘶吼出的梦想、那些宛如年少赌气一般狠狠铭刻下的理念。我们曾意气飞扬地说要征服全世界。若是这样的光景永远无法实现,那么就让我们在终末的黑夜降临之前将自己燃烧殆尽,换千分之一秒的几率成为宇宙中明亮的超新星。

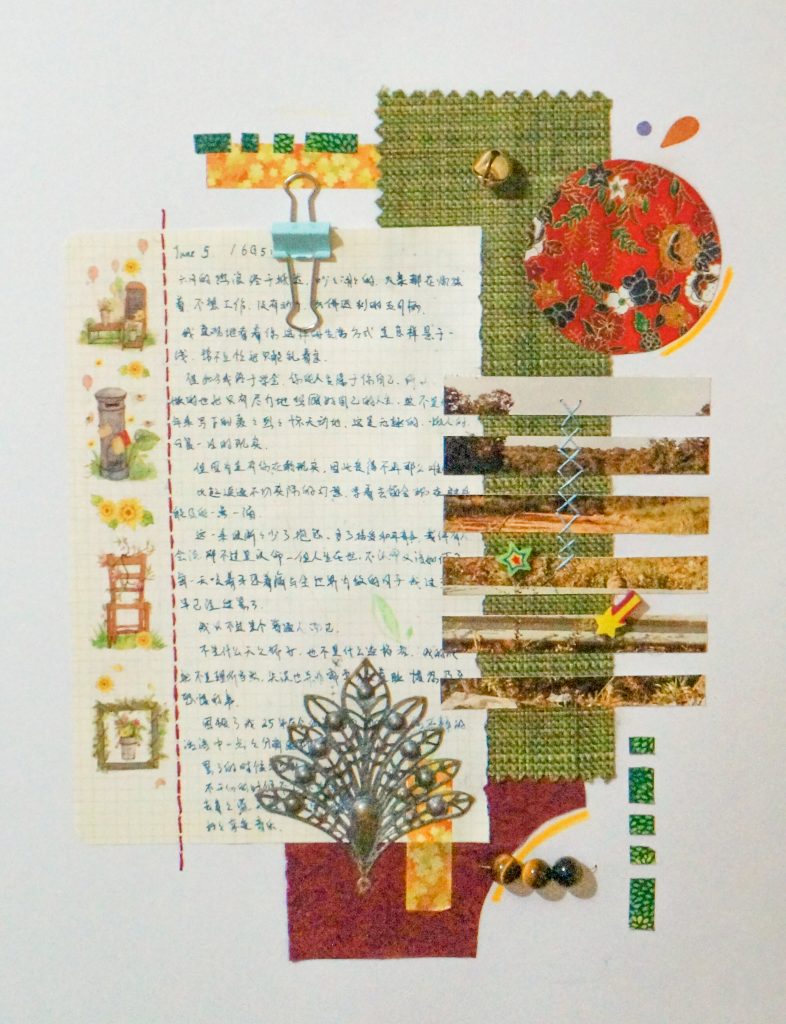

Hence, with too many unspoken thoughts and suppressed feelings, I found my peace and validation in written conversations with myself—prose, poetry, essays, written in my mother tongue. Nüshu was born because dreams were forbidden and cries were never heard; its exclusiveness provided the necessary privacy and security that allowed these women to walk themselves, sisters, and even daughters (Nüshu was often taught by the mother to the daughter), through hardship and dismay. Similarly, the Chinese language naturally creates an environment in an English-speaking nation, allowing me to sit with my most private thoughts, uncertain feelings, and honest vulnerabilities. However, without Nüshu’s exclusiveness, my writing has helped me foster a powerful sisterhood with other Chinese women. Some reside in other parts of the United States and aided in validating my feelings of loss, disconnection, and displacement; others live in the Midwest and have been waiting to communicate with someone other than themselves about their experience.

“我不确定小姐姐你会不会收到我的这封信,说不定你把我给忘了吧。我是17年那会儿跟你配对日记的妹子。当初小姐姐你突然间就不见了,等了好久都没见你回来写日记。之前搜你贴在主页的网址也搜不到了。之前我还看到来着,我记得你是一头橘红色短发来着,看着很凌厉。我也不知道小姐姐你在掌阅写的书叫什么,不然就去下面戳你。不知道你现在发生了什么,祝安好。如果小姐姐看到我这封信记得给我回啊,回什么都无所谓。总之我知道你还好好的就行了,也算放下我的一个执念。”

Hidden Letters opens with these lines: “To provide each other with hope so they continue to live, the women created a language men could not read. It was called Nüshu.” Similarly, Chinese women in the Midwest who failed to find their emotional and spiritual home locally have turned to their mother tongue for the same purpose: to create hope for each other and for ourselves. When writing in these scriptures illegible to “the others,” we can finally speak our minds fully and freely without fearing judgment or being bullied.

May it be Nüshu or any language and system we choose or conjure, ultimately, we are only trying to cheer ourselves up. While many believed the system was created to rebel, for me, Nüshu was the fascinating realization of what I imagined transcendental sisterhood and ultimate self-acceptance look like. As He Yanxin, one of the oldest Nüshu users, mentioned in the film, Nüshu was about sisterhood. Because every Chinese woman could use a sister connected by heart instead of blood or race. Until we find that person, we retreat to our bedroom, explore ourselves, and reconstruct our identities with private letters and intimate conversations with ourselves.

Listen.

It’s a sister’s gentle whisper: Continue to speak. Continue to think.

About the author: Xiao Faria daCunha is a practicing visual artist and an independent journalist covering what’s happening in the Midwest belt, focusing on lifestyle, art, and culture. Her visual art practice includes mixed-media illustration on paper, printmaking, and mixed-media collage. Xiao was the former Managing Editor for Urban Matter Chicago and her bylines have appeared in Chicago Reader, BlockClub, BRIDGE.CHICAGO, KCUR, The Pitch KC, and more. Xiao’s artistic and writing practice explores the intimate, vulnerable truth of the BIPOC, migrant, immigrant, and diaspora communities. She considers everything she does art journalism and aims to speak on behalf of those who haven’t been heard and shed light on what hasn’t been seen, whether it’s emotional, cultural, or societal. By weaving her personal experience with public narratives, Xiao creates emotional and engaging conversations to interrogate, challenge, and advance existing perceptions of women, Asian diasporas, and other immigration populations.