¡Sí, Se Puede! is on view at the Glass Curtain Gallery until November 4, 2017. The show features the work of Victor Alemán, William Estrada, River Kerstetter, Nicole Marroquin, Victoria Martinez, Gloria “Gloe” Talamantes, with offsite murals by Hector Duarte and Sam Kirk. Each of the artists took engaging approaches to working with documents from the UFW archives and I caught up with Meg Duguid, curator of the exhibition and Director of Exhibitions at Columbia College, to talk about how this manifested in each of the different pieces.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes: So my first question is what was the inspiration for the show?

Meg Duguid: This exhibition actually came about a little organically. We were approached by a partner of our office of Multicultural Affairs, now called the office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, who said that he might have access to the archives of Cesar Chavez and would we be interested in doing an exhibition. Long of it short, we said we would be interested in doing an exhibition, but we are a liberal arts college who focuses on Art & Design and media production and so we would be interested in putting together an exhibition that utilizes the Chavez-Huerta and UFW (United Farm Workers) archives as a site for production and that’s where the impetus kind of came from. How to merge this iconic and amazing history with contemporary art practice and the archive as site of production. It became a way to do that.

JPC: And so you felt it was important for it to become a creative engagement because the position of the school as a liberal arts school?

MD: Absolutely and the kind of creation of what our students do on an academic level.

MD: The artists were selected very, very carefully given their history with looking at archive history, passive resistance, and their kind of engagement with research. An interesting side note is, as we developed the project, all of the artists have this amazing dual practice as educators and artists, and those two things sort of fit in as one practice for the artists in the show. That became a really interesting kind of flashpoint, for lack of a better word for how the artists deal with their practice, but also for how the UFW dealt with its practice in terms of getting people on board for the boycott and its acts of resistance. So I feel like in a lot of ways, the artists sort of individually act in the way that the organization acted.

JPC: It seems like different artists engaged in different ways with the materials from the archive. What would you say the range to the approaches are?

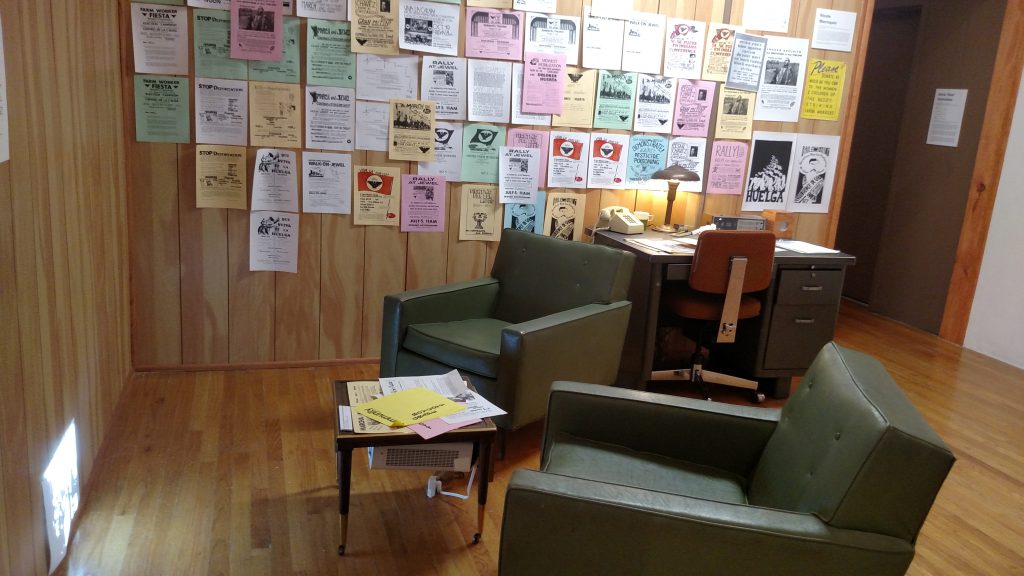

MD: The range to the approaches were really quite wide. So we had River Kerstetter who engaged in pieces of texts within the archive, literally quotes, and he letterpressed those quotes onto fabric and created a tablecloth as a point of conversation. And then William Estrada, who engaged with this really interesting aspect of the UFW. Every flier that the UFW put out was often a simultaneous call to action, while also being a call for collaboration. So often, the works, the posters, the fliers, the newsletters, would literally have these blanks where either individual offices could fill in certain information or individual organizers could fill in information, or people could write their stories back so that they could be used to help promote and advocate for the cause. That is something that seemed unique to that grassroots organizing of the UFW and it something that has since been utilized by other social activists. William Estrada engaged with that by taking an image or letter in the archives and only pulling out one of the taglines from the logo that says “To Love We Must Fight:” and then he left it blank. Within that blank you can you know get, “To Love We Must Fight Hate,” “To Love We Must Fight For Each Other.” You as the viewer can fill in the blank with markers. I think that was a really interesting engagement of something inherent in many of the fliers in the archive.

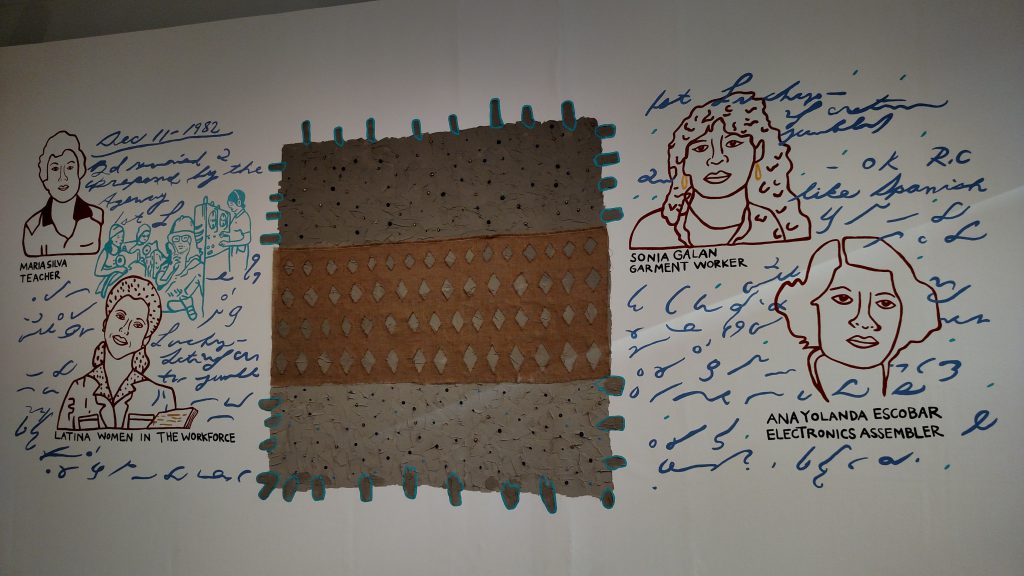

Lastly, Gloria “Gloe” Talamantes recreated a newsletter that was put out by the UFW, “El Malcriado,” and she recreated it as “La Malcriada.” And in Spanish, if you call someone a Malcriada, it does not always have the best of connotations. It usually means uneducated women or surly women and it is not true of its male counterpart, which is something that can be considered just fine and a point of pride. So she put out a female focused newsletter in which multiple people contributed articles. Interestingly enough, through this project, she found out that her father, Luis, actually worked in the fields of Texas and Arizona. So she interviewed him as her part of the newspaper about his experiences. And that is kind of an amazing piece of history that came out of that. That piece is located within a recreation of one of her murals. And that mural is located at 23rd St and Whipple and it is part of her Brown Walls project where she artists she invites paint over where graffiti blasters have painted walls brown. They become these acts of rebellion against the graffiti blasters. It runs throughout the show.

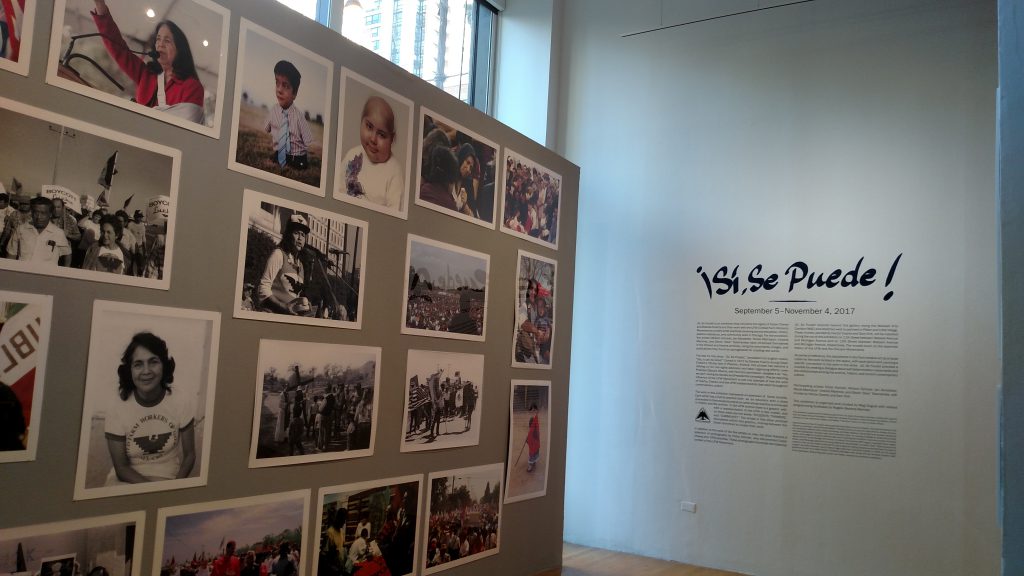

And of course when you walk in, there are these series of photos by Victor Alemán, who was the Cesar Chavez’s photographer and photographed UFW activities for over ten years in the 80s, so there is a section, I’d say of just around 30 of his photos that help create a historic context for the other work. And in the front, in the window space of the gallery are four or five documents that different artist worked with in the archive itself, so it acts as a codex for the entire show.

JPC: I saw in the copy that there are some murals being created in conjunction with the exhibition. Can you tell me a little bit more about those?

MD: Yes, and Sam Kirk’s mural is up. So I can give you images of that. And Hector Duarte’s mural is going up. Sam Kirk did a mural based on young Dolores Huerta. It’s called “The Seeds We Plant Today Determine Our Growth For Tomorrow” and in the mural there is a young Dolores Huerta with her hands raised and her hair comes out into this farmland that’s growing. It’s beautiful. The mural references classic muralism. It’s very referential to mural history, the history of the UFW, and the need for contemporary acts of resistance. And it also highlights female strength within it, which so often we see men taking the helm.

Hector Duarte will be installing in the third week of October. He’ll be installing a mural on 11th street and Michigan. It’s going to wrap into the alley and wrap around the first floor. It’s a fence that has a hole in it with butterflies coming through and the butterflies are symbols of migration and immigration. It’s very tied up in the need for immigration and a more accepting border.

JPC: My last question is what would you like people who are seeing the show, what kind of new perspective, or what you like your audience to take away from the show.

MD: I guess I want my audience to take a few things away from the show. I want them to take away from the show the need to know more. More about the UFW movement. More about Chicano art history. More about Chicano history in general. This is a really good question because no one has asked me. The need to know more is something that I want them to take away and I want them to have that. I guess I think about Hector Duarte’s mural kind of being about migration and immigration and I think about how little about immigration we have been taught, especially when it comes to Mexican and Central American immigration. Because we are responsible for that immigration. We brought people through in the bracero’s program to be migrant laborers and then sent people back or asked Mexico to repatriate them. We did that multiple times. The bracero program being the last of that time. And then we have turned around and punished people for coming to this country under the same programs that we ran. And those programs might be taught maybe in the Southwest. But they certainly weren’t taught here in my upbringing. Granted, it’s been a while since I was in school. And it seems to me, given all the conversation about immigration right now, it would be really nice to have a conversation about immigration, what it looks like, and how policies are a part of that.

I’m not sure that you would take that away from the show and each artist individually dealt with the subject matter so poetically, so personally, and so within keeping of their work that I guess I would really think that people could and should take away this idea that the personal is political and that politics is not separate from our daily acts and our daily living. That within that, it becomes a different interpretation of the world, and different interpretations of resistance and I hope that people would take away a point where they can find themselves within their own interpretation. Oddly enough, you’re the first person to ask that. I feel like I spent so long with each project and finding out how they relate, that I don’t have ONE thing for people to take away.

Featured Image: Mural Translation, 2017 and La Malcriada, 2017 by Gloria “Gloe” Talamantes. White and blue flowers with red centers bloom against a brown backdrop the color of graffiti-blasters’ paint. A pile of “La Malcriada” sits in front of the painting. Image by Rob Karlic.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.