At least a year before the opening of her newest show, I met Carris Adams in her capacity as an arts administrator. Adams works as the General Manager of Chicago Art Department, an organization that provides space, support, and opportunities for artists. As the first Core Critical Writing Fellow at CAD, I got to see Adams regularly organize a stream of events and exhibits but all the fellows, myself included, also knew about Adams’ work as a visual artist. Her work has been exhibited in various spaces in Chicago, Texas, and New York, including The Studio Museum of Harlem. We took a moment to meet near CAD and her studio at La Catrina Café to talk about her upcoming show.

Carris Adams’ solo exhibition Doubletalk is her first exhibition with Chicago’s Goldfinch Gallery. The exhibition will be on view from the opening reception on Saturday, May 11 until Saturday, June 22, and a conversation between Carris Adams and Jinn Bronwen-Lee will take place on June 8, 2 p.m.

Adams’ drawings create pressures and textures with graphite on paper to underscore the significance of signs. In our brief conversation, we spoke about how race and class impact some choices that are made in creating signs for businesses, but we also talked about the idea of a self-imposed/self-inflicted residency, balancing acts of self-care, going to the gym, rediscovering the joys of reading, Piggly Wiggly, and unexpected messages in invented spellings and decaying signs encountered in daily life.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tara Betts: Hello, Carris Adams. How are you today?

Carris Adams: I’m making it, I’m making it. How you doin’?

TB: I’m doin’ good. It feels warmed up once you say hello, even though we’ve already been talking…it changes, but I’m curious what was your process in getting started?

CA: My process in getting started in making the drawings? Well, Claudine Ise, the director of Goldfinch Gallery, we’ve been talking for a couple of years back and forth about getting a studio visit or something. We finally met in 2017, probably early 2018. I’d just left my position at Rebuild Foundation and I was taking some time off just to have my own like self-inflicted residency and I was just like, I’m just gonna have my own residency for a couple of months.

TB: Which is good, right?

CA: It was really great. I watched Game of Thrones for the first time, and so, you, know, I was just like, what is this, and I was like texting my best friend and I was like, they died! Did they really die?

TB: Are you keeping up with it now, still?

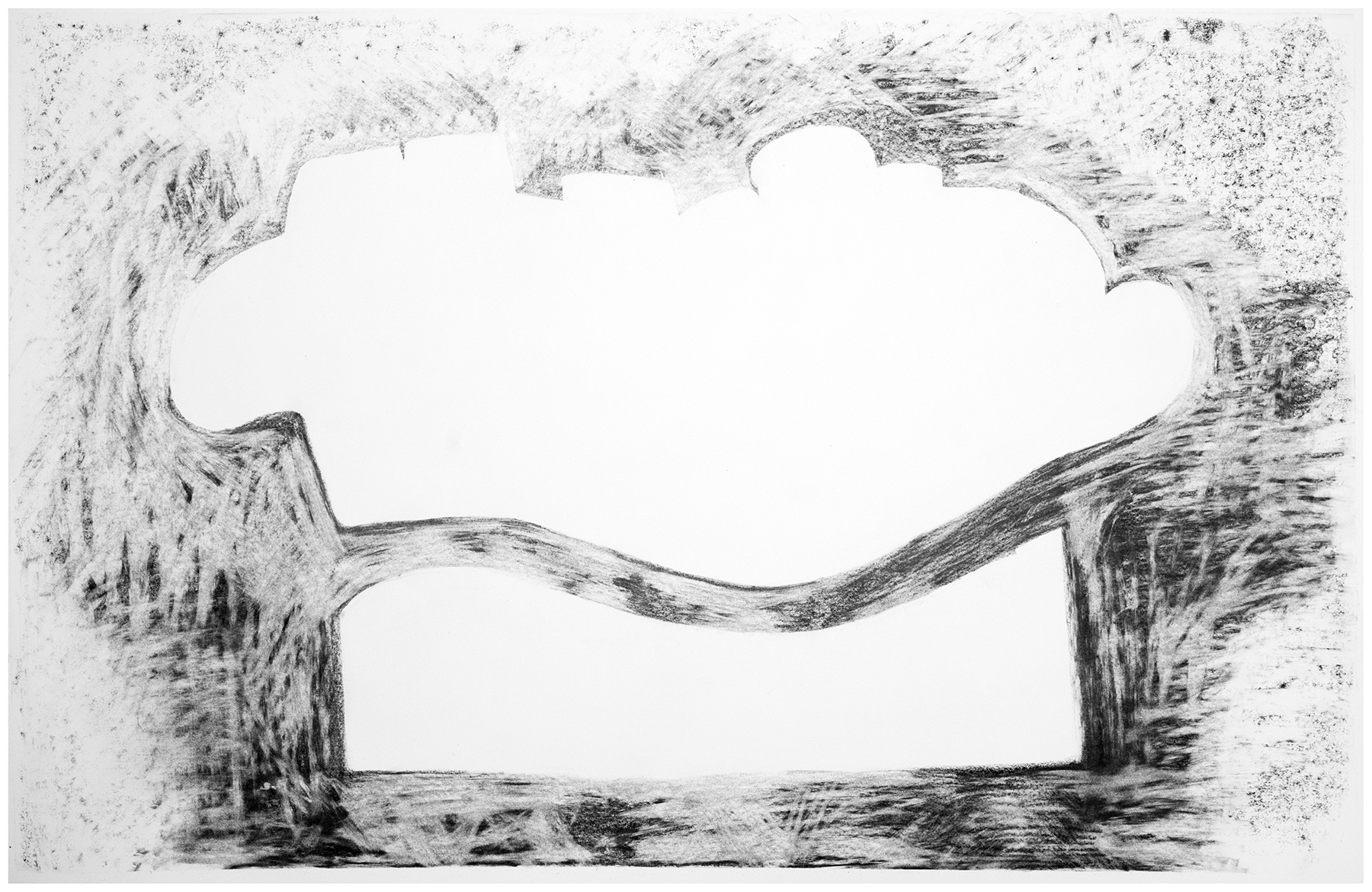

CA: Yeah, yeah, I’m already caught up. I’m all the way caught up. But it was just like I was watching In Living Color and Living Single, I would just go through all this stuff, and the drawings were happening. The drawings started to happen because even during that time, it was a self-inflicted residency. I just didn’t want to make paintings on canvas anymore. I was tired of it, and I really didn’t understand why we still did it. You know, it’s like almost 2020, and we’re spending a ton of money on canvas? It’s a long winded way of saying I just thought to back to a basic thing. And there are moments where you make a sketch for a painting, and the sketch is better than the painting, and you’re always trying to get the painting to look like what’s in the sketch. I just consciously decided that I didn’t want to do that, you know, and I’d just rather make the sketch into the larger drawing, and focus on drawing. In that same vein, drawing or using graphite as a legible material, I just thought to use it to make things like sign drawings that were glowing, you know, things that were kind of ambiguous. That’s all I thought about it. It wasn’t too much. I was just like, I have these couple months off. I can’t not make work. I can’t not have a job and not make work, you know. I need to utilize this time.

TB: Right, it’s a constant balancing act.

CA: Yeah, so I was going to the gym like a crazy person but it’s like, what else can I do in this time? My mind just really kept going back to these sketches I had made – these would be great drawings, so you should just make drawings.

TB: I think people sometimes think art is this process where you’re plotting out things like blueprints, and I don’t think it always works like that.

CA: Not at all, not at all. I think that a lot if it is way more intuitive and spontaneous than we’d like to believe. I do through the process of seeing something, taking a photo of it, maybe visiting it a couple times if I need to, as in that thing that I saw, and making a sketch, and then having – I really do think, oh, this is what it’s going to look like in the end, so that when I start I’m moving towards some kind of purpose. But then, that always changes and then I have to rethink. What are the formal qualities that are happening here that are going to influence what I wanted a viewer to think about or feel in the end? And so, it goes like that.

TB: I know I was thinkin’ a lot, too, like when I was lookin’ at the pieces that I previewed online, They remind me of when people do rubbings, like going to a cemetery and doing rubbings on headstones or signs because it has the indentations or the raised points. So, I was wondering how many of the sketches were based on actual signs? Or were there particular signs that got you started?

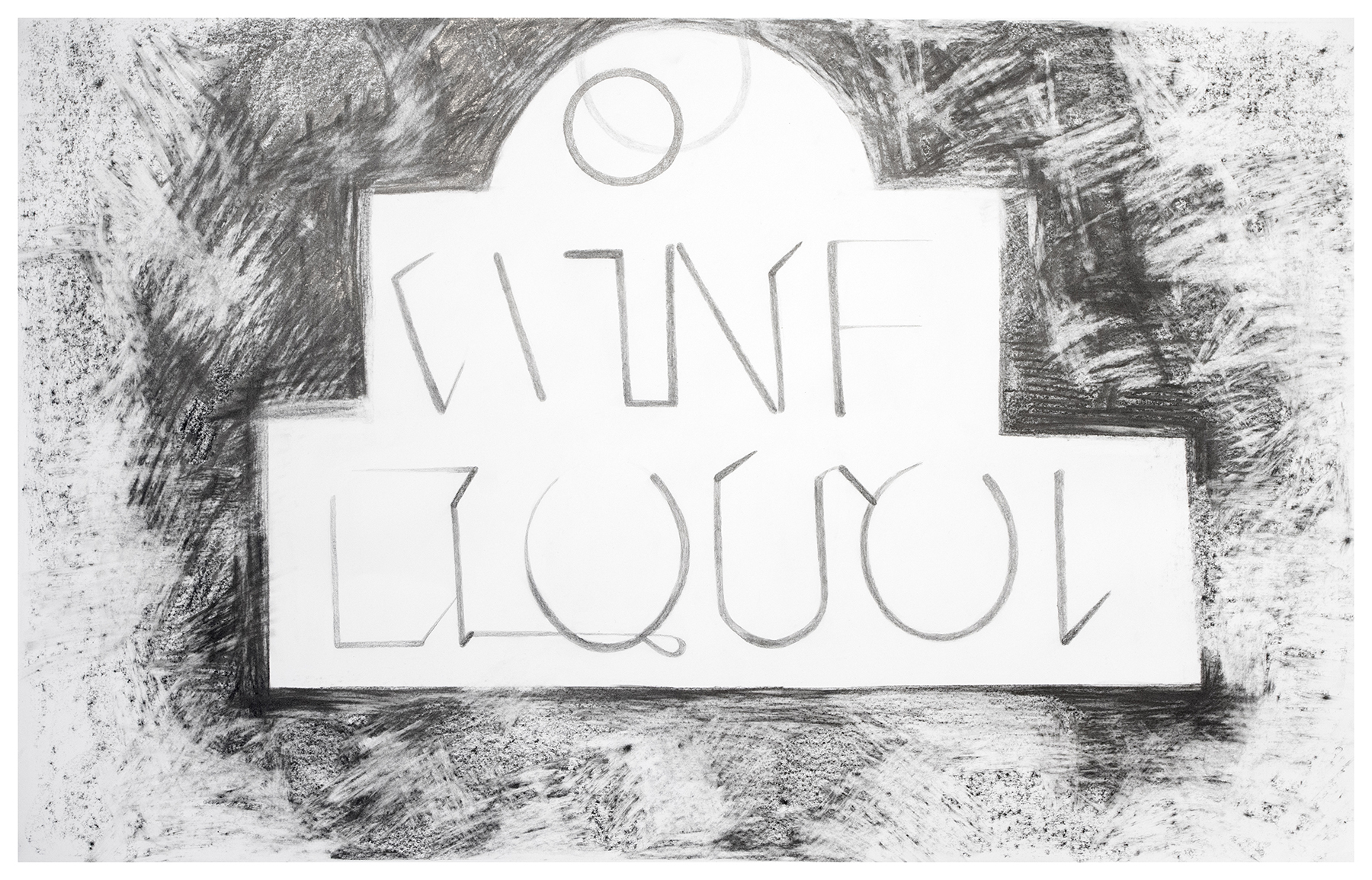

CA: They’re all based on something actual, so one of the first ones was a sign that I saw a couple years ago in Andersonville and it says: “wine liquors” and it’s a kind of art deco-style sign that doesn’t quite make sense, you know because of how it’s shaped? It’s old and that was one of the things that I liked about it. You can see the shadow of the neon that the light was casting but you couldn’t see the actual neon. If that makes sense, so you saw all these weird lines and this texture that was rotted away from it, but you couldn’t see the actual neon bulbs, and that was like maybe three or four years ago. And I had made a sketch of it, and I was like, oh that’s cool, but in my mind I kept thinking like, it can’t be that simple, you know? So I have to move beyond that in some way. And during that time off I was just like, well, you know, I’ll make these and we’ll just see what happens. And it was in that that I had started it, that was the first one, it is in the show. They’re all untitled, they’re part of series titled “Thick” but the works individually are untitled. So that one, as the first one anyway, I was using this graphite and I didn’t like the mark that I’d made so I tried to erase it. And that erased mark was better than the thing I had been doing. [laughter] So I was like, just keep erasing!

TB: [laughter] Right, and there were a couple of ‘em, I found myself thinking about how there’s just enough line to make out maybe a couple of letters in a lot of them. I was thinking about “Queen”?

CA: Yeah, there’s “Queen” where it’s very architectonic in that way.

TB: You see the “q” and the “n” but everything else is kind of amorphous. And I love that it makes your brain work to figure out what the words are, you know, and it’s funny how quickly your mind can jump to match that, or you’re trying to match it, you know?

CA: And that’s what I liked about it because I did that same jump when I saw that sign. I was it in Texas – have you ever been to Texas?

TB: Not in a very long time.

CA: Well, it’s still probably the same. [laughter] It’s still big and sprawling and the highways are like ten lanes, or something crazy, because they have to just take up all the space. And I was driving to visit a homegirl who just bought a house, and there’s Queen Beauty Supply – and it’s like this huge sign on a pole on a side of a highway that is kind of too much for that beauty supply store, you know it’s some beauty supply store, it’s not…

TB: I feel like I need to look up a picture of the actual sign now.

CA: I think it was on I-30 [laughter] and there’s some road called Jim-something, I can see it in my mind. It’s right across from like a Walmart, of course. It was huge. You’re going down this highway and there’s this big old pole up in the air, and it says “Queen,” but it was too bright, like someone hadn’t adjusted it properly. So you’re like, Queeeen, and all you saw was the “Queen” but the “Queen” was too bright and the “Beauty Supply” wasn’t lit at all.

TB: So, it’s in the dark.

CA: It’s in the dark screaming “Queen” to everybody else on the highway, across from the Walmart. And I was just like, oh, that’s interesting, then I sketched it out. When I was at her house, I did a little sketch for a second, and then you know that was a couple years ago, and I thought that would be a great drawing one day. [laughter]

TB: [laughter] I think it turned out all right.

CA: And I hadn’t made drawings like this – I had made one drawing like this with graphite and architectonic lettering in grad school, and it had taken so long because it was 120 inches long or something crazy that I never wanted to do it again unless I was really, really sure about what could fit that theme. And so, that’s how that style has started to come back up. And the “Queen” one is very much in line with that one. It was called “Almuflihi” and it was used in a project with Allison Glenn called “Messages in the Street”– that same kind of taking the lettering or the letters and kind of squishing them together, then making this kind of pitch, you know, kind of like a point.

TB: Right, kind of like a little tent or something.

CA: Yeah, just taking up space and each of those letters being some kind of idea of themselves and then everything else around it is whatever we want to make it.

TB: Right. I think we do that with language too, like I could picture people saying if they were going to go to that beauty supply store, they’re not gonna say all that. They’re going to say, “I’m goin’ to the Queen, what you need?” [laughter] So if you think of it that way, the signs kind of mirror the language, not just the language being a sign, you know?

CA: Yeah, they do. That’s one of the things that I like about signs. You start to point to class, and you sort of point to race and class. I don’t know if they can always be divided, but in places where the economic – let’s say like lower class, right, not middle class – things are very clear: it’s like “food and liquor,” you know, “fish.” Things are very much to the point. In that, if the language is to the point, it’s usually the art around it that gets a little bit more imaginative.

TB: Yeah, or more colorful, too.

CA: Or more colorful, yeah, like those crazy – I was always like, what’s with hot dogs here? People like hot dogs, like the Chicago dog.

TB: There’s nothing like Chicago-style hot dogs.

CA: Yeah, I moved here, I was like, what’s this about? You know, why are there pickles on it?

TB: And poppy seed buns.

CA: Yes, and buns. There’s just this whole thing, and it will say something like “Joe’s” and then this whole mural that he probably spent a ton of money on is about the hot dog. You know, about the idea that this is going to be the best place. And I love that, it’s like, why not? Everything else sucks.

TB: And then for Chicago, there’s always Harold’s Chicken – now lots of artists are doing signage like Harold’s Chicken.

CA: Yeah, I’ve done a few paintings, a few like Harold’s Chicken – the running man. I like the running man because it’s kind of a violent image if you think about it.

TB: It is! You’ve got the hatchet with the action lines of him running – behind the hatchet there’s action lines, and the chicken’s like, “I’m out!”

CA: Yeah, and it’s just like the kind of drawing that recalls a very specific time, you know. It’s very quick. You can tell he just had a friend do it, you know, and they turned into this whole thing, but it’s just a weird image. So, I’ve done a few paintings, it’s not in show but Claudine has them in the gallery, because I was also in love with this kind of glowing that’s in the graphite drawings. There’s a painting in the show, it’s a neon-like effect of lights and glowing, and the color associations with those things or the color play between them. So, a motion is suggested, something is beaming out light, or is accepting light, like in the chicken man paintings – he’s running, you know, those two-channel runs? It’s like a leg up and a leg down. When I was a kid I was fascinated by those because I was just like…

TB: The limbs in alternating positions…

CA: Yeah, I always wanted to know like how did that work, you know, [laughter] like how can I make that thing? I was always trying to do that.

TB: Right, and then just thinking about can you catch the locomotion of it correctly in a two-dimensional frame.

CA: Yeah, yeah, and just like go all out, just continue to be crazy with it. A few of those are in the space, they’re not necessarily in the show, but they’re around and they’re online. It’s a lot of light, I’m thinking about a lot of light and, of course, darkness because you can’t have one without the other.

TB: Especially if it’s just graphite, right? What were some of the challenges to work in that kind of constraint?

CA: One of them is probably like just finding the right paper that had the right tooth, you know, but because I’m an artist and we hoard materials, you know. I had the paper for a minute and just didn’t know. And I don’t think it’s anything special, it’s just a Stonehenge Printmaking Paper, a paper that I always liked since undergrad, so I just continued to buy it, you know? [laughter] But my hope is to move into vellum and these other papers that are more translucent, so that I can mark on the front and on the back and see what that does.

TB: Which would be cool because those papers kind of glow.

CA: Yeah, they have their own glow to ‘em, so that’s the next move. And I found someone that sells it, but like real vellum, and not like the sort of plastic, polyester vellum that you get at Blick, something a little bit more sturdy and archival. But the graphite is pretty simple, you know, there wasn’t anything that was too surprising. I think it was just about, it does require you to, if you are this kind of artist, you have to be sure about the mark that you’re about to make, or sure that when you erase it, you’re fine with what that’s gonna leave too. It’s not just gonna leave quietly, I think, so there’s that. So don’t get it on your hands and smudge it all around, little stuff like that, but it wasn’t anything unfamiliar. The painting, however, it’s a new turn, because it’s not on canvas. It’s on billboard vinyl. That’s its own kind of challenge because billboard vinyl isn’t porous at all because it’s supposed to be outside. I knew immediately that I would have to sand it and reapply my own ground to it to get the paint to stick to the surface, but even with that, it’s not a good material for painting thin layers. They just kind of move around. It doesn’t absorb anything. So, the first try of that painting was pretty bad. It’s like building a house and painting it at the same time. I just had to really learn what that material can do, so that’s been interesting.

TB: I’m wondering since you talked about Texas, where you’re from, I’m wondering about the transition from Texas to Chicago. How has that informed what you’re creating, if at all?

CA: It has, I’m sure. In Texas I was interested in these things, but it was a little too, I don’t know – myopic is definitely not the word because that’s the opposite of what I’m thinking of, or maybe it is – it was a little too pointed. If I was interested in the “Queen Beauty Supply,” if I was interested in the Food & Liquor, I was interested in objects inside of the thing, like those things that you only could get at those kinds of places. I remember there was a soda water that I liked that came in this really sleek blue bottle. I always felt so adult when I was drinking it as a kid because my aunts would drink it. It had strawberries on it, or something like that, and like pork skins. [laughter] And I knew I could only get those things at that store, you know, and that I could get my stupid ramen, and my brother would get a sandwich from the grill – I knew I could only get those things there. So I was always interested in the objects inside, and I wasn’t quite sure about it, but I always thought that thing was too simple, and so I put it away and made paintings while I was in Texas. So when I came to Chicago, I think I was just simply encouraged to work to go through that phase of looking at signage and looking at objects like great big sunflower seeds or Now & Laters, the purple ones. [laughter] I was encouraged to think about those objects as something to take home and how that’s colloquial in a lot of ways. It changed in that way; I think too, I think here just the congestion of everything – you have to look more, you have to look differently – I didn’t have a car when I first came here, so having to relearn my north from my south, where all these things are, and how specifically the lines of the neighborhoods are really hard. They click really fast, which is so telling of like class and accessibility. You can go under a bridge and you’re in this whole new place, you know, and how the language changes: when you’re in that space, the language of objects changes too, you know. All those things become unearthed a little bit more.

TB: So have you seen some signs where you see a really dramatic change from like some of the signs we’ve already been describing?

CA: Like something right next to each other?

TB: Right next to each other, or maybe something that’s just dramatically different from being so direct or being even like a Harold’s Chicken sign – how do they become more subtle, or just how does it just deviate from the other signs?

CA: I think they try to become more mysterious, you know, when I was off of Randolph somewhere and there’s this place called like “Art and Science” –

TB: The hair salon!

CA: The fucking hair salon. I didn’t even know that that was a hair salon.

TB: I get my hair cut there. [laughter] I go to the one in Wicker Park.

CA: But I didn’t know it was a hair salon. I was going to see Weirdo Workshop at City Winery. Walking down the street, you can tell. When I first moved here, no one had to tell me that used to be a meatpacking district – if you know what you’re looking for. it’s a meatpacking district. It’s a whole bunch of warehouses that spill out into the street, you know, that’s meat!

TB: That’s what the whole Fulton area was.

CA: Yeah, in New York, the old Meatpacking District has a very specific look? Oh, okay, this is what this is. You see old signage where’s it’s like “such and such meats” which is always kind of weird– “meats.” What kind of meats? What does that mean exactly? But you’ll see that next to like “Art and Science” where I was just like, Oh, what is this new initiative? [laughter] I thought it was something else, and I’m walking past, and I’m like, Oh, it’s a hair salon. [laughter] And nothing wrong with that, I’m sure –

TB: I’ve thought about that too! Like how their sign, there’s no scissors, there’s no pictures of hair styles, it’s very subdued, it’s like “A + S” on a little banner hanging on the outside, at least for the one I go to.

CA: Yeah, yeah, and I think there’s like atoms around a nucleus or something, and that’s why I was like, oooh! That’s another thing that’s happening in arts. It’s always happening where artists try to merge sciences and technology, and that’s why I was like, what’s that place? And it’s a hair salon. So things happen like that where they start to get a little too much. They try to get mysterious or sexy with the language, you know? Versus just being like “Hair Salon.” But I like hair salons. I have a painting that’s called “Miraculous Hair Salon” and it’s over in Chatham, and if it was just called “Miraculous,” I don’t know if I would know it was a hair salon but it’s the combination of the two. In the space, a predominantly black space – I’m pretty sure Chatham has to be 98% black, you know – there’s someone who’s claiming that as a miraculous space, that miracles happen here – I don’t know if that’s insulting to the client or not.

TB: Right, I’m thinking that could either be really flattering or really insulting.

CA: Yeah, it could totally be insulting, but then we do go to hair salons to feel better, you know. [laughter] We go to feel better.

TB: Yeah, I wanna feel like a miracle when I’m done. [laughter]

CA: Exactly, exactly. I like that feeling of walking into a place and being like, Oh, this feels good, and there’s a transformation that’s gonna happen here and that can be cool.

TB: But it’s interesting, it makes you think about how signs kind of document a certain feeling people want to have, but then also they can document the history of a place, too.

CA: Totally, a lot of the drawings in Doubletalk are silhouettes of something that’s no longer there. So that mystery that’s happening is this kind of mystery that can point to something like art and science if you want it to, you know, but I mean it to be a little more interior. You have to project onto it what you think it is or what you think it could be in that you’ll be creating your own space simultaneously while this thing doesn’t exist. There are so many places where things are gone, you know, because they have to move on to something else. And I think that’s hard for everybody. It’s also just like, well, is this the way that we live, you know?

TB: I think so, to some extent. But also it kind of says something about if there are certain signs that stay with us – what do we want to preserve and what do we want to hold onto, right?

CA: Mmm hmm, I have no idea.

TB: Was there any sign that you were definitely like, oh my god, I have to do this one?

CA: No, I don’t think so, I don’t think I thought about it like that – do I have to. I just knew that like it would happen. “Miraculous Hair Salon” was one of those where it was also just like the store sign window was also beautifully painted and someone took their time and they thought about it and it’s been there for a while, and it just had a nice feeling to it. There’s things that I see where I’m like, oh yeah, this is the painting. I haven’t seen anything that I haven’t made that I thought it’s a loss. Like Josephine Halvorson, who’s one of my favorite painters, there’s an article…she did write something that’s called like “The One That Got Away” and it was some kind of like crazy steel object that she had drove past that she wanted to go back and paint and when she went back it wasn’t there. There’s also a book – Lisa Lindvay who’s a photographer here mentioned it to me as well and it’s a book that like “photos that we never made” or “photos that got away,” something like that [Photographs Not Taken: A Collection of Photographers’ Essays edited by Will Steacy]. It’s a collection of essays by photographers, these images that they wanted to snap but they couldn’t, they didn’t do it for some reason, and that that thing stays on their mind forever.

TB: Yeah, I feel like that about poems sometimes.

CA: I figured y’all do.

TB: If you don’t write that phrase down when you saw that thing, then you’re gonna lose it. You were talking about the Miraculous Hair Salon, I keep thinking – I know it was on the south side but I cannot remember where – there was a hair salon called Preddi and Penk. [laughter]

CA: [laughter] But “Penk”?

TB: Yes, it’s spelled like: P-R-E-D-D-I and P-E-N-K – for a minute I was like, wait, what is – and then I thought, oh, it’s Pretty in Pink. One, nobody’s going to have that name, but you have to have a kind of particular attention to your dialect to even get it that that’s what’s happening. I was like, that’s smart! And it was literally like these pink cursive letters on the side like a professional sign, I was like, I’m sure whoever made this was like: “you sure you want this?” [laughter]

CA: [laughter] Yeah, “you sure you wanna do this?”

TB: But it makes sense.

CA: I love that because that kind of thing is you claiming the space, you know, claiming it as your own space, and a space for people whoever your audience is. We should be able to do that. I think I’m kind of over – and it sounds bad probably, I’m sure it sounds really bad – but it’s the same reason why people are like, “I’m not watching no more slave narrative movies,” you know? I’m kind of over talking about the shittiness of the world in this way, so what are the other ways in which I can reimagine something, or like point to how we project onto a thing. So like “Preddi and Penk”? Go ahead, you know! Do your thang. [laughter]

TB: Yeah, it feels kind of proud too, and there’s nothing wrong with that. I like that it kind of butts against like we have to be proper, even when we sit down and get our hair did, we have to be proper then, too? We have to be proper at breakfast? We have to be proper in the nail salon? [laughter]

CA: I think, in this day and age, we have seen that that doesn’t work.

TB: It doesn’t. And it’s kind of nice that even the signs can start to buck up against that kind of respectability.

CA: I think that’s awesome – go ahead, Preddi and Penk. [laughter]

TB: I’m gonna a check the spelling but I knew it was like “penk” was definitely p-e-n-k.

CA: And I love it because it’s like, you know, like you said, you have to have a certain dialect to get it but right when you said it I was like, Oh, it’s pink – “penk” is pink. [laughter] I haven’t seen it but someone told me of one that was like “Weaves and Tees,” and it was in Chatham somewhere. I was like, go ahead, do what you want.

TB: Everybody wants a nice new t-shirt and to get your hair nice and crisp.

CA: Yeah, and while I don’t always make paintings of things like that or things that we think of as like icons of blackness in that way, I think there’s another way of just putting something like in the space and letting you project onto that and you’re doing that same thing of recreating something, you know, if that makes sense.

TB: Yeah it does, now it makes me wonder what are some of the impressions that people have had of some of the signage that you’ve captured. What kind of questions or thoughts do they come to you with?

CA: Usually the only question is, “Is it real?” For the most part, no one’s seen these drawings so it’s very new, and the paintings are very new. In the other paintings, people always assume that thing doesn’t exist or they question whether it exists or if it’s something I made up.

TB: Why do they think you made it up, though?

CA: I have no idea. [laughter]

TB: Part of me wonders if it’s a particular audience that would think it’s made up or who’s more likely to believe it, or like, well, it could be across the spectrum.

CA: Yeah, it kind of is, it kind of goes everywhere, it hasn’t been like one particular group versus another or a demographic versus another. Mostly it’s just like: is it real? Where did you see it? One of the big misconceptions that people think that all my things come from black spaces, and that’s because I’m black, so they’re gonna assume that things come from black spaces.

TB: But where are some of the spaces that you have found that weren’t black that you thought were interesting? Cause when we are talking about “Art and Science,” we don’t know who owns that.

CA: No, we don’t know who owns that. I think there are places that you’ve called out like Chatham or Back of the Yards, but you know I’ve seen things in like Bridgeport which is historically anti-black.

TB: True.

CA: I live there and everyone kept telling me, “I can’t believe you live there!” And I didn’t understand why.

TB: Yeah, It used to be very anti-black, and now gentrification is like: “We want these buildings.”

CA: Yeah, I think people don’t have a choice. And the people that were there are dying and their kids don’t want to deal with it, and that’s the way of the world, you know, so they’re selling off their stuff. They just don’t have a choice because the city is also exploding in population, it’s growing so much that people can’t really be too picky. I’ve seen things in Bridgeport, one of the things was in Andersonville. I saw something else in downtown St. Louis, I saw something at a Piggly Wiggly in Mont Eagle, Tennessee.

TB: What is even on the Piggly Wiggly sign?

CA: A pig who’s got big eyes and a little hat, and then sometimes it’s his tail – it would be his tail on one end and his tail on the other. [laughter]

TB: See, I grew up in the era of Moo and Oink where you had the cow and pig in the commercial and they’re in the logo, but it’s just their heads and the logo.

CA: Yeah, that’s probably another set of small paintings, something weird one-off painting is that I just want to do something with Piggly Wiggly. [laughter] I love Piggly Wiggly, I don’t know why.

TB: And that’s a very Southern thing, too.

CA: I saw more up here in the Midwest than I’ve seen in Texas – I mean there are so many Walmarts in Texas.

TB: Really? See I’ve never seen a Piggly Wiggly in Illinois. Where they at?

CA: They’re here, they’re here. I saw ‘em here, I saw ‘em out in Wisconsin, I saw them in Tennessee too. I’m going to make a Piggly Wiggly painting – I just like the pig and I like how goofy he looks. The one in Tennessee, the eyes were inverted so the whites of the eyes were actually red so it looked like an evil Piggly Wiggly, and I was like, That’s a painting. It happened just like that, I was like, oooh!

TB: And it’s in all places where people love to be like, “I’m going to have bacon and eggs, meat and potatoes.”

CA: Yeah, like old farming towns and stuff. I love it. I was like, oh, I hear about these – let’s go inside! And it’s just a grocery store, but I bought a t-shirt and everything.

TB: I’m dead now.

CA: Mmm hmm, they have Piggly Wiggly t-shirts where he’s taking a selfie – it’s so cute.

TB: So they gotta anthropomorphize the pig.

CA: Yeah, get him up to date. He’s gotta catch up and see what the kids are doing. Some stuff is everywhere and sometimes I like things formally and that’s okay. Like with the Chicken King sign or even Miraculous Hair Salon, it was just an interest in why work in color? Or even the Piggly Wiggly, his inverted eyes. It can point to a whole bunch of things but it’s also just funny for what it is.

TB: I almost wonder if you can get the graphite effect with a colored pencil kind of thing – is it possible to do that?

CA: Sometimes there’s a colored graphite I’ve been experimenting with lately, but the colors are really dull. It is something on my mind so I bought these graphite sticks that were kind of expensive for what they were but they’re super soft and they’re kind of an olive green, a deep blue, a gray-blue, a light gray, and a brown – that was my first time seeing a colored graphite, not a colored pencil. It could probably be done, of course, but it just takes some experimenting. That is my next step, though, trying to add that colored graphite to is and see what happens.

TB: That would be fun because I’m thinking if you’re playing with the different papers and the different colors. It’s all the stuff you want to touch.

CA: You do want to touch it, but it’s also that colored graphite is way softer than a pencil so it’s flaky almost, almost like chalk, and that was surprising. So it will lend well to that on the paper, but in making a stark mark like a regular graphite pencil would, I’m not sure it would do.

TB: But the layering and the colors could be really cool. Do you kind of see that as one of your future directions or where do you think things should be headed after this show? Where do you dream of being headed after this show?

CA: [laughter] I dream to be in a fucking warm place, you know…Well, I’m probably going to continue. There’s still some more graphite drawings that I want to make in this vein. Things are gonna start moving away from legible language for a little bit so I’m excited about that, or like partial language – like the Checks Cashed place by my house, the c-h-e of “checks” has been out for months so only the c-k-s is lit, and only the c-s-h-e-d is lit for the “cashed,” and I love it. When I’m tired this happens where I’m trying to pronounce it, and I was like, cckss. [laughter] I swear there was one of my favorite things that I’ve seen and it was never going to be like a drawing or a painting, for no reason but it just wasn’t going to. It was a licence plate and it said: I LOVE GSUS. And I was so tired and I was like, “gisus”? “Geesus”? “Geeses”? [laughter] And by the time I figured out it was Jesus, when I tell you I laughed so hard, and I was so tired. Work was shitty. I was in a bad space, what I perceived to be a bad space – usually it’s fine – I called somebody immediately and I was like, oh my god, I just saw the greatest thing! Stuff like that where’s it’s slightly legible, I’ve been interested in. I’m going to continue these paintings on billboard vinyl, see where that goes for things that need to be painted but there’s a lot of drawings happening in the future. Even to some degree, moving into objects – objects also have language in them as a sign or signifier of something else, so experimenting with that a little bit. We’ll see though. I tried this and things ended up being drawings or paintings.

TB: You kind of encapsulated how things have kind of been experiments for you to see how it works, then you go, okay, this is what’s working. I’m also intrigued when you think about it, how many signs do we see, you know you talk about the letters going out, then there’s like a whole other language when those letters fall out. I can’t help it, my inner twelve-year-old just cracks up when it becomes a curse word or something, or it’s a dramatic misspelling, I just start cracking up! People are like, what’s so funny, and I’m like, the sign, the sign.

CA: Yeah, that’s the writer in you, too, so that’s always fun. So I chuckled cause I was like, cuks? But I ride past it every day, and I know that it’s the end of “checks” but still there’s something in my mind like, oh no, you need to pronounce that because it has to mean something else. So isolating those little moments – they may mean nothing, that’s fine by me.

TB: Was there anything on your playlist, reading list as you were creating?

CA: Have you read Thick yet?

TB: I have not read Thick: And Other Essays yet, I want to. Tressie McMillan Cottom?

CA: Yeah, I was reading two things at the same time while I was making these drawings: Tressie McMillan Cottom’s Thick, which is why the series is named Thick. When she talks…this kind of, the idea of thick research, you know, in school to have thick research is to have gone through it thoroughly, but then also like taking that same idea of thinking and moving through the world, that you have to move through it thickly. So that’s why I thought that would be an appropriate title for the series of those drawings. I was reading that which was really cool, and I’m always listening to something Roxane Gay has said, and I was reading Marlon James’ Black Leopard, Red Wolf because I just love his stuff, and it’s all very imaginative and out there and confusing and crazy. I don’t know if I was listening to – I can’t think of anything in particular I was listening to, I have so much music. But I’m definitely trying to read more; I used to read a lot before grad school.

TB: Yeah, grad school does something to your reading function.

CA: It does, and it kind of scars you as well. I’m not a good person to read for the sake of arguing a point, you know, like I’ll read something and it’s like, alright, that’s what they said. [laughter]

TB: Right, I like to think of it as in conversations where they have connections and associations with other texts.

CA: Yeah, and I had to learn to do that in grad school, that was really hard. So after grad school I didn’t read anything for like a year and the first thing I read was some shitty, shitty mystery novel by Janet Evanovich – I’ve been reading her books since I was in high school.

TB: But you know what, that is okay. [laughter]

CA: They’re so bad! They’re so predictable, but it was this entry into getting back into reading so I’ve been trying to read more.

TB: I think you need it still because post-graduate school or if you’ve went through this big inculcation/indoctrination, you need to put that to the side and process what happened, and rest. But you still want to be actively engaged, so that totally makes sense. I’m like, let me go read some self-help books and look at SARK or read erotica…something that’s not forcing me to be on or super intellectual.

CA: Grad school was a big learning curve because I had gone to UT Austin for undergrad. It took me like seven years to get through undergrad because I had to work to pay for it. So, it was like on one year, off one year, on one year, off one year, so it took forever. UT Austin at the time wasn’t invested in any kind of art theory or art philosophy even. So, when I got to grad school, I was having to read all these people that everyone else in the room had read, so it’s like, I gotta first say their names correctly [laughter] Just like, Saussure…

TB: And bless you for getting through it.

CA: I got through it, it was hard but I got through it. But doing that kind of catch up was so traumatic that the first thing I read at the end of all that was Janet Evanovich. I got into some Junot Díaz and started to get back into some other things, but it was hard – I’m still coming out of it. And it weird, I didn’t think it would take that long, but it’s totally taking that long on top of work and stuff.

TB: Well, I think it takes at least a year for every two years of graduate school. That’s my equation.

CA: I’ll take that because I graduated in 2015, so it hasn’t been that long. I’ve done a lot but it’s hard to remember. I’m always kind of runnin’ so I’m not good at being present in the moment enough to see the thing, I’m constantly having to think about the next thing which is also anxiety, about survival. I’ve met very few black people, and I say black people specifically because I don’t think “people of color” is inclusive to some kind of like – I don’t think we’re all on the same side all the time –

TB: Yeah, and also, too, in Chicago, when we look at the employment rates for black people and how they’re going low, low, low, low, low, and then they’re going, “Why are black people leaving the city?” And I’m like, job – it would be nice to have a job.

CA: For sure, and we – you and I and several people that we’ve met – have bought into that kind of system of getting an education or whatever that’s put us ideally or symbolically in another class bracket. But paycheck-wise, we are not.

TB: You’re still scrambling.

CA: All to say that I haven’t met any black person, especially a black woman, who isn’t constantly thinking about the thing she has to be right now and the thing she has to do tomorrow, and the thing for next year, you know? My friends and I, we talk about it all the time, like, how do we do this? How do we stay present and think of all the stuff. And reading helps.

TB: Reading always helps because then I can unplug from everybody else –

CA: You’re going to be able to do that at your residency.

TB: Yay! The thing I’ve admired about seeing you at CAD (Chicago Art Department) is that you go and you work out regularly. I’m like, I need to get to that level – I can walk for a good thirty to forty-five minutes, beyond that, I need some work. What has been successful for you as an artist, particularly as a black person, as a woman, in Chicago, in terms of trying to shoot for balance? Do you have any basic steps that you want to give other creative people who might be in your position?

CA: Asha Veal and I were just talking about this yesterday – she’s a curator and educator in the city – we were just talking about this yesterday. I don’t have anything; I think if I did I probably would be in a better mental state. [laughter] What has helped is for one, knowing – it sucks to be a person and to know all the things that are stacked against you, like I can only imagine our parents and our grandparents who knew that they could do more but that the system wasn’t set up to enable them to do so, which has to really suck. So in that, you and I are not special, it’s just been our circumstance that we have been able to do a little bit more. So I try to keep that in mind as much as possible. Mentally or even emotionally, making work helps. If I’m not making work, I’m a pretty awful person. I go to the gym way too much, and it’s really to exhaust my mind.

TB: But it does alleviate anxiety, too. And that’s part of the reason why I’ve even walking, you know, because I know I need to burn some of that energy.

CA: Going to gym, having great friends around – I think too I’ve been fortunate to show and to show consistently and I don’t know if there is a secret to that or what, but I just try to make my work. I’ve said it often, I’m never worried about the paintings or the drawings, I’m never worried about making things – I’m always concerned about my livelihood, you know? [laughter]

TB: That’s the big question all the time.

CA: Because if that doesn’t exist then I can’t do the other things. In that those things are always mine, and I try to stay comfortable in the fact that this could be the highest point that I ever make it as an artist, and I have to be okay with that, you know? So now what?

TB: I also think you may be doing what you’re doing for a really long time, or you have big, high points in the road, and you’ve got ebbs and flows, and that’s okay.

CA: Yeah, and I think, you know, I’m young, I just got out of grad school a couple years ago, and I’m trying to model my practice after painters that were great mentors to me. Albeit, all of them are men, I don’t know why, but they were. And the art market, there’s that as well, and who succeeds and who doesn’t, there is that patriarchy.

TB: And also who supports them in their success, right?

CA: Yeah, so that’s its own thing. I was just like, I just have to do what I’m gonna do, and leave it at that. It’s still hard, but it’s this is where I am right now. [laughter]

TB: And that’s a doable thing, it’s not an impossible thing. Some days it’s easier than others.

CA: Yeah, I guess that’s a good way to describe it. Some days, it’s just easier than others. For the work, I’m just not concerned about it because I know I’ll make it. I know that I will make my objects. I know that they’ll be with me forever maybe, but they’ll be made. [laughter] It’s about the other things that can get worrisome and from there I just try to keep pushing. I think I have to be aware. I’m super aware that if someone’s asking me to hold their hand through the thing, it’s because I’m blacker than them, whether they know it or not, you know? And female and cis. And I have to be, like most people I know have to be super cognizant of that kind of double consciousness for lack of a better term, which is exhausting, but I constantly have to be aware that. Okay, this person is asking me to do xyz because I’m a black woman.

TB: And sometimes you gotta say no.

CA: That’s what I mean, so if you can see that, then you can say no to it. And saying no may harm you, quote unquote, however you think about harm, but then, who cares, who gives a shit. [laughter]

TB: And sometimes, is the “no” worth an opportunity? Is the “no” worth it to preserve your sanity, that’s really the question.

CA: Exactly, so Asha, the reason we were talking about this, she’s teaching a class at SAIC, and it’s supposed to be women in arts administration or something like that, with an emphasis on women of color, as broad as that can be. She was going to bring up curators, and administrators, and educators, and all these people to talk about their experience and how they got through it, and I’m willing to bet that most all of them are going to have something to say about not being listened to or heard, but then getting to the place where they are and how they leverage that. For me, one of those is just saying no. I would rather not – like most recently, someone wanted to write about my work and they didn’t know how to talk about it, like the thing that they sent me was very off, then having to sit down and being like, goddamn, I have to do this for you, you know? [laughter]

TB: Well, I hope I haven’t made this one difficult.

CA: Not at all, Tara Betts. [laughter]

TB: Which is funny because I’m just now reading art critics on art theory. Frankly, the extent of my understanding of art theory is videos by Henny Yungman, Art Thoughtz? Some of those are really smart when you really know what he’s talking about, and they’re hilarious. But that’s the most art theory I’ve probably had exposure to aside from recent reading.

CA: No, that’s fine, but I think poetry and fiction, those things are all cousins. I think you can talk about those all with the same qualities – the texture of something, it’s all image-making. I’ve seen you read a poem – your hair was long –

TB: Oh, that must have been a long time ago. [laughter]

CA: Your hair was long and you were wearing some red at the Promontory – it was The Breakbeat Poets thing.

TB: Oh, I had on my Wu-Tang shirt. It’s a reproduction of the shirts worn in Raekwon’s “Ice Cream” video, so it has the big red “W” on it.

CA: I remember the crowd was going crazy, and I was there because Krista [Franklin] was reading from that book, and we were teaching together. I’ve always been a fan of poetry. I’ve been a fan of Roger [Bonair-Agard] before I knew who Roger was… So I’m pretty sure it that you’re in that other book that I have too, I just didn’t know it, but the way that people talk about your work, and the way you have with presenting it and it moving a crowd – this is the same.

TB: Thank you.

CA: The thing’s with poetry, especially when you’re having to read it, it’s kind of ephemeral, it moves through space and kind of disappears or something until it’s printed, that’s always fun.

TB: I think that’s why I gravitate towards print. It’s not just because I studied journalism. It’s why I like interviewing people. By doing the print, I know it’s going to have a lifetime beyond saying it, and I’m not a person who bounces all over all the time being performative. If I’m in the poem, I’m feeling it but I’m not going to be overly demonstrative.

CA: That was funny too, because at that reading I remember – what’s his name now, he had the locks, he edited the book?

TB: Quraysh. It was Quraysh Lansana, Kevin Coval, and Nate Marshall who edited the book.

CA: I remember him introducing you in that way. He said, “She don’t do this often, so we gotta do it.” And I remember your hair was long.

TB: It’s been a little while, yeah, and I’d just finished the Ph.D.

CA: I remember them saying something like you weren’t here. You were in New York.

TB: It was, it was a rough time because speaking of that idea of balance, after I finished my Ph.D. and a number of losses, I still wonder how I made it through that? People think you just keep soldiering on. I’m like, no, you need therapy, acupuncture, some meditation, walks, and listening to affirmations where they teach you you’re the soft baby chick – whatever you need to do. [laughter]

CA: [laughter] The soft baby chick is just holding you like, it’s gonna be fine.

TB: “You are precious, you are loved; everything will be okay!”

CA: That’s like a different kind of gray area where you see everything that is happening in front of you. But all of those gray areas, I think being an artist, you are in a perpetual gray area, and some days are just harder than others, some years are just harder than others. And in that, you may have to go to the gym too much, or just do whatever is you need to do to not lose your shit. So this last year in Chicago, that’s why people haven’t seen me out anywhere – I’ll go see a show but I don’t go to openings – I can’t deal with any more energy other than mine right now, or than I have to for work or something like that, that’s as much as I’ve got to deal with.

TB: Or even as a poet, I find myself going to select literary events, but I don’t want to go out to a variety of things. I wanna go see Avengers: Endgame. I wanna go bowling, or I wanna go for a walk, and do normal human stuff. That kind of balance is important.

CA: It is, I haven’t seen Endgame yet, and that was one of the things where I’m like, maybe tomorrow, I’ve been thinking about it as that kind of therapeutic thing. I wanna go in the middle of the day. [laughter]

TB: Yes, you wanna wear your soft pants.

CA: Yes, I almost was gonna put on sweatpants this morning, like I’ll go in the middle of day, be my old lady self with my little blanket, [laughter] and just leave me be, let me watch these three hours…I need to be prepared to sit there for three hours. I’ve tried all the things…to stay as balanced as possible.

TB: And that’s good to know. I think a lot of artists want that reminder which was why I asked.

CA: I heard someone say, “Take the meat and spit out the bones.”

TB: Yes, I’ve heard it, I don’t know who said it.

CA: Yeah, someone’s just like, “Take the meat, spit out the bones, honey, so I’m gonna say it – do what you want.” [laughter]

TB: Yeah, but that’s what you do, right? You cast out the stuff you don’t need.

CA: The thing is like I’m learning that that’s just a constant thing and what I’m try to do is be one of those Zen people…where you can say, okay, this is happening and I’m going to be fine. [laughter]

Featured Image: Untitled, 2018. Graphite on paper, 30″ X 40″. Photo by Jasmine Clark. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tara Betts is the author of Break the Habit and Arc & Hue as well as the chapbooks 7 x 7: kwansabas and THE GREATEST!: An Homage to Muhammad Ali. Her interviews and features have appeared in publications such as Hello Giggles, Mosaic Magazine, NYLON, The Source, and Poetry magazine. She is part of the MFA faculty at Chicago State University and Stonecoast – University of Southern Maine. When she’s not teaching, Tara works with dedicated teams at Another Chicago Magazine and The Langston Hughes Review as Poetry Editor. She also hosts author chats at the Seminary Co-Op bookstores in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood.

Tara Betts is the author of Break the Habit and Arc & Hue as well as the chapbooks 7 x 7: kwansabas and THE GREATEST!: An Homage to Muhammad Ali. Her interviews and features have appeared in publications such as Hello Giggles, Mosaic Magazine, NYLON, The Source, and Poetry magazine. She is part of the MFA faculty at Chicago State University and Stonecoast – University of Southern Maine. When she’s not teaching, Tara works with dedicated teams at Another Chicago Magazine and The Langston Hughes Review as Poetry Editor. She also hosts author chats at the Seminary Co-Op bookstores in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood.