Read this essay in Mandarin here.

“We are lesbians from China, none of us have a great relationship with our moms,” I said.

“No, we probably have bad relationships with our dads more,” someone replied.

“No, babe, we don’t have dads.”

As a group of lesbians reflected on our families at Linye Jiang’s art opening at 4th Ward Project Space on Sep 14, we all laughed. We’d been talking about our families, and without anyone prompting us, we kept using the same words: “和他们不太熟” meaning we’re not really familiar with them. As we kept talking, it became clear the absence was more specific than that.

The phrase echoes across diaspora communities, in different languages, in different contexts, but always with that same careful distance: 和他们不太熟. We use it about aunts and uncles we see at weddings, about cousins who moved away, about grandparents from another era. Mostly, we use it about our fathers.

Isn’t this a familiar pattern for Chinese lesbians? He might be there physically -though not guaranteed. But we have never had a full conversation. We do not call, they do not call us. We might send them sporadic pictures of ourselves pretending that we do not have the piercings, tattoos, or hair colors that we choose to have. When we actually do talk, we do not learn about each other’s private lives.

Some glimpse of his life might be gained, not through him, but through our moms digging up childhood pictures (of which we have no memories). Maybe then, we talk about our separate lives a little, but only a little. We use codes and euphemisms to feel more comfortable, reserved, and Chinese. And maybe he comments on how we are so grown and successful now, he’d never imagined that we are even doing better than he ever did. And then we go on our separate ways and live our separate lives.

This pattern repeats across families, across generations. Silence becomes a survival strategy, when families learn to love through gaps and gestures, when entire communities practice the same careful not-knowing. While walking through this exhibit we’re looking at how power shapes intimacy and how history fragments connection.

What Is Not There

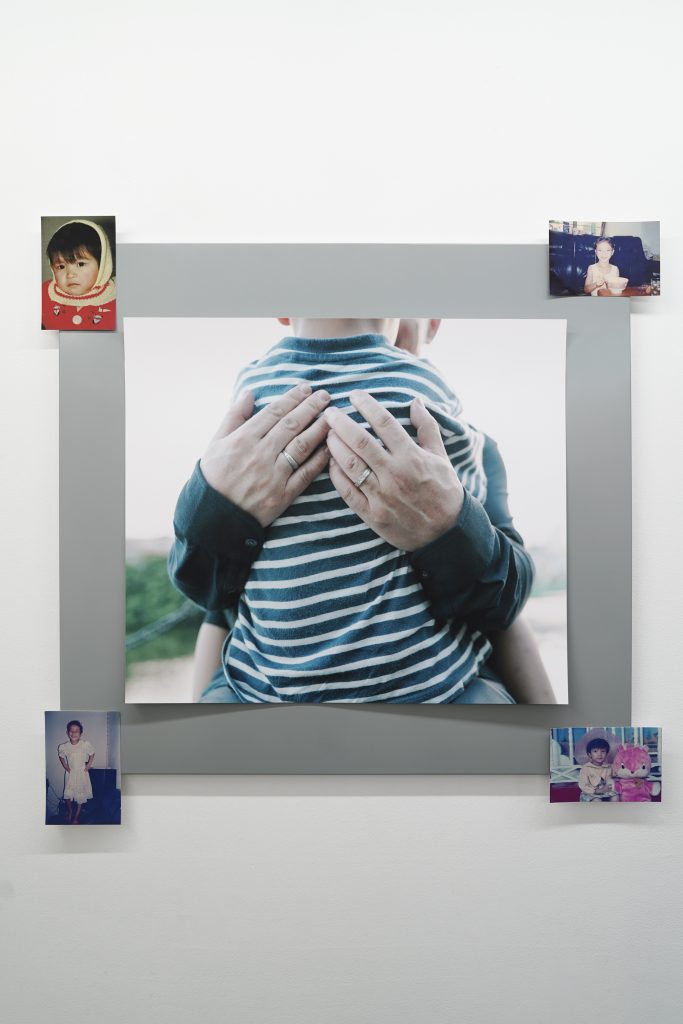

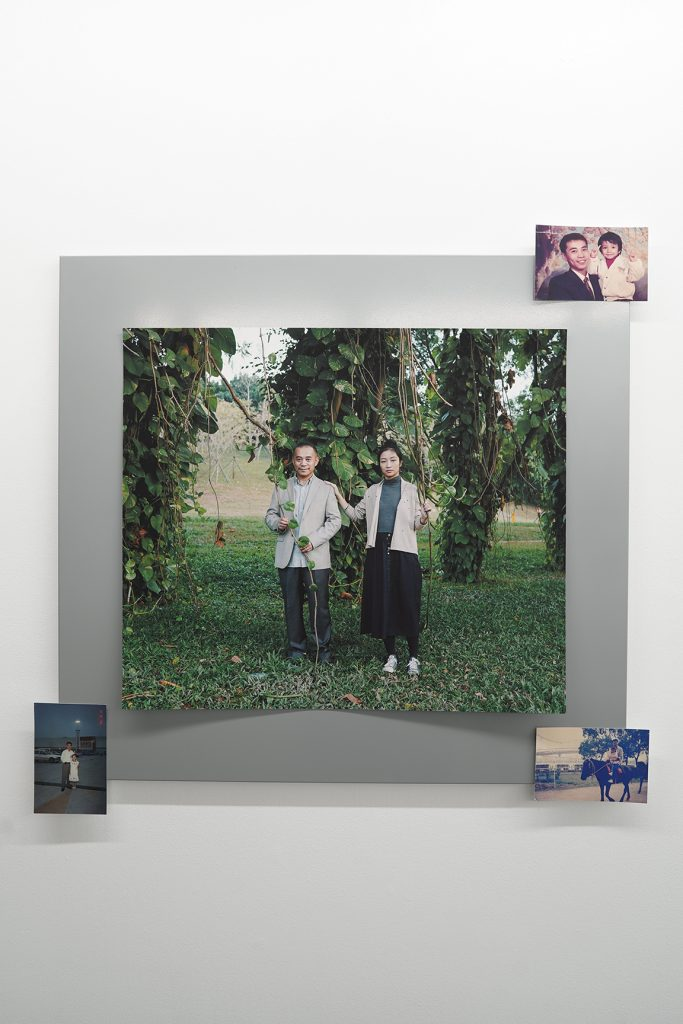

This conversation kept coming back to me as I stood in Linye’s show. Her practice centers on archival inkjet prints mounted with magnetic tape on metal boards – a technique that makes family photographs feel both preserved and precarious, permanent yet moveable. The magnetic mounting allows images to be rearranged, removed, reconsidered – mirroring the work of memory itself.

Some hang alone on metal boards. Others are layered with her own larger photographs from 2018 and 2019, creating a dialogue between then and now, between the child she was and the artist she became. There’s young Linye, happy and outgoing and beautiful next to her parents. There’s her son Shun with his grandfather, three generations on one board. History repeating but different. There are photos of her dad and mom together. One can assume: Isn’t this the picture-perfect family?

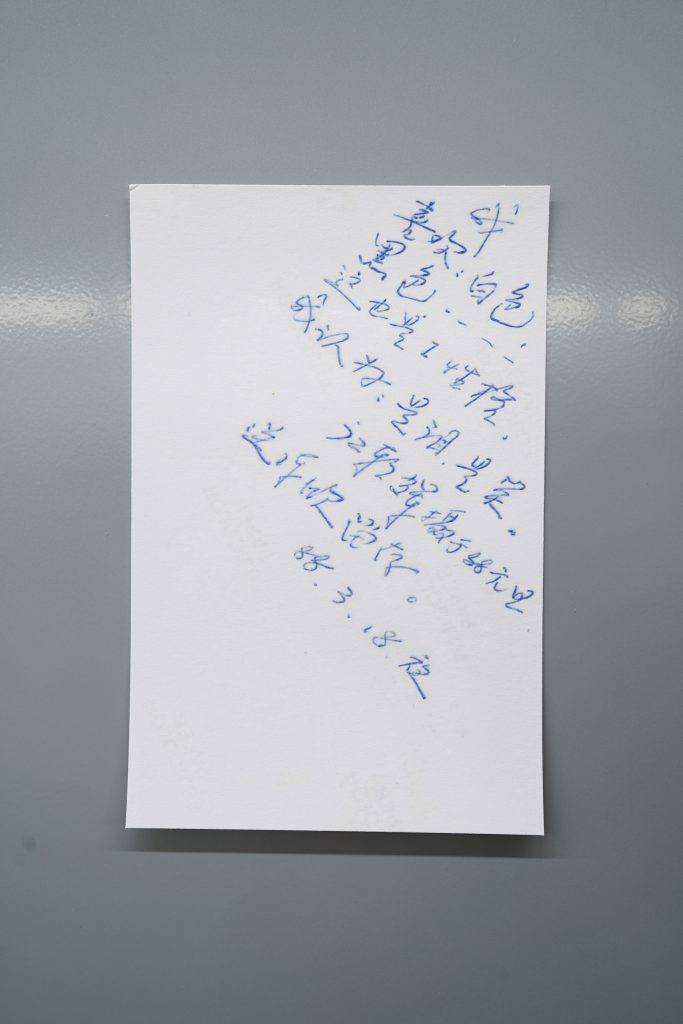

But then you notice something else: on the back of her father’s 1988 portrait, a handwritten note that her father wrote to his brother-in-law Chen Xin, “I Like: color white / Black … / This is also I personality / I think it is tears, it is laughter / Jiang Chaohui, photographed on New Year’s Day, 1988 / For Chen Xin to keep / March 18, 1988, night.” The intimacy startles. Poetic, vulnerable, addressed to another man, meant to be kept. This note would have remained hidden, pressed against the back of a photograph in storage, if Linye hadn’t turned everything over, examined every surface. The exhibition makes you wonder: what else is written on the backs of things? What other intimacies are archived in reverse, meant only for specific eyes, preserved by accident?

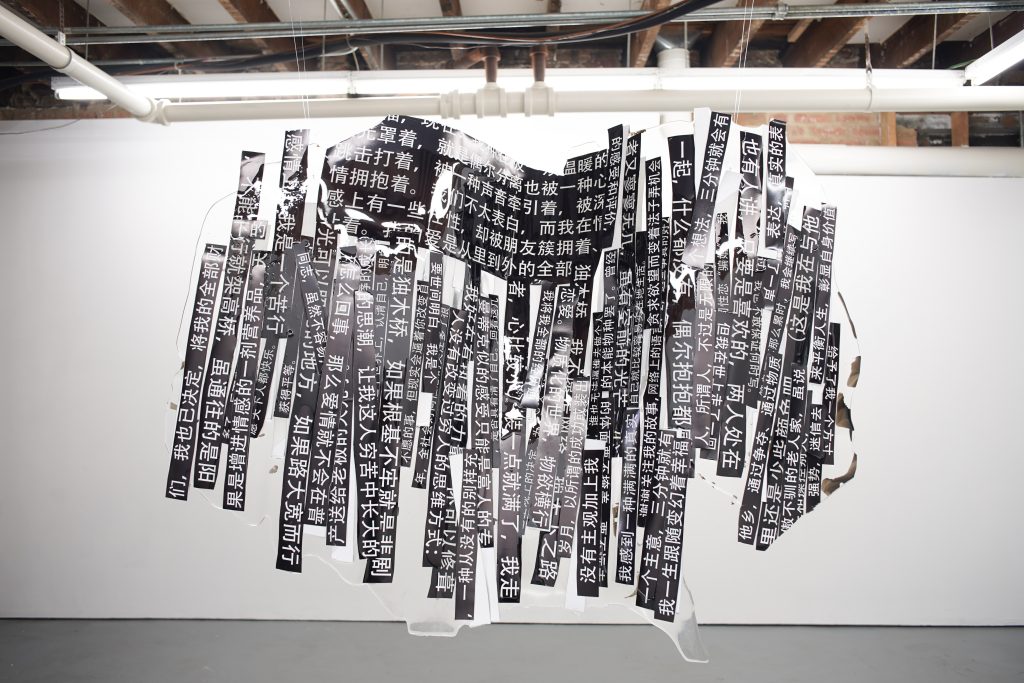

Hanging in the middle of the show is a sculpture titled, Excerpts from my father’s novel Shenzhen Story: my boss and I, made from prints embedded in resin, made from pieces of her dad’s ten-year online novel – an anonymous life as a gay man that she discovered at fourteen but could only confront him about years later, as an adult living in Chicago. That’s what this show is really about: what is not there.

In those fragments of his writing, he writes so beautifully about gratitude for strangers who listen, about the tenderness he feels for his anonymous readers. He writes crudely, unfiltered and urgent in his desire. He writes in pain, opening his wounds sustained from the struggle of his desires, his felt stigma, and his hopes that his country would change in his favor. He is a full human there in the pieces, especially as he writes “谁也无法逼谁去做个人” meaning no one can force anyone to be a decent man.

In Linye’s family, the wife gets the “respectable” husband. Brother-in-law gets something intimate enough to write by hand, something worth preserving on the back of a photograph. Anonymous online community gets his raw queer desire and pain. Does the daughter get the full human? We do not know.

The careful distribution of his different selves also speaks to larger forces at work. The forum where he published his work for ten years, where he gained so much admiration and love from a community of which his daughter was not allowed to know, was shut down suddenly in 2017. “因不可抗力” – due to unmovable forces. That’s how the forum announcement read. 不可抗力. Unmovable forces.

天涯社区 “一路同行”(“Fellow Travelers” – the 同 doubles as both “together” and 同志 “gay”) had been running since 1999. Eighteen years of queer stories, emotions, and literature. Welcoming novels, essays, poetry, and personal writing, the announcement had said. Overnight they sent a message out to its users, “Please save your personal data yourself. Thank you to all moderators and users for years of hard work.”

If there were no archives to preserve his work, it would simply no longer exist. Linye’s sculpture is rescue work as much as it is art. It hangs in the center of her show because it has to. These clippings of sentences that touched her are all that remains of that entire community. Personal family secrets and state censorship work the same way: they disappear queer voices, make love invisible, turn intimacy into archaeology.

Anonymous, Named

Both Linye and her sister found their father’s writing separately, by accident. Linye found it on the family PC when she was fourteen. Her sister, twelve years younger, found his Blued app on his phone. The methods of discovery shifted with technology, but the pattern remained: this, is how queer knowledge gets passed down when direct transmission is impossible, through digital archaeology, through stumbling across what parents thought they had hidden well enough.

Two generations both scavenge, but in different ways. He wrote anonymously online, building community through coded stories and careful distance. She makes art under her own name, exhibits in galleries, talks publicly about queerness. Not sure which one is louder. Not even sure why it would be a competition.

I Like: / color white / Black … / This is also I personality / I think it is tears, it is laughter / Jiang Chaohui, photographed on New Year’s Day, 1988 / For Chen Xin to keep / March 18, 1988, night. Photo by Linye Jiang.

Maybe that’s the wrong question. Maybe the question is, “what different historical moments make it possible?” He came of age when being seen meant being endangered. She grew up when being invisible meant being erased. Different forms of courage, different possibilities for voice, different relationships to risk and safety. These are two registers of possibility. His words carried through an underground forum. Hers hang on the walls of a Chicago gallery. Both are acts of survival. Both are incomplete without the other.

We don’t know if the daughter gets his full humanity. But she inherits his methods. The exhibition strips away explanatory text, leaving you to discover connections the way she had to discover her father’s writing: through careful attention, through noticing what doesn’t quite fit. Both father and daughter work through fragments, through what can be said obliquely rather than directly. He published chapters of his novel online over ten years, allowing meaning to gather slowly in an anonymous forum. She arranges and rearranges family photographs across metal boards, letting viewers assemble their own understanding of what happened in this family. Both work with the same dualities in visual and written form. Presence and absence, what’s shown and what’s hidden, the image and its reverse side.

She tried since she was young, tried so hard to be free from her family that felt wrong and constricting somehow. She knew she was queer since she was young. She talks about queerness. There is a sense of her that is so similar in artistry to her dad, but so different from him. The parallel is almost too perfect: two queer artists in the same family, creating work about desire and identity, but separated by language, by generation, by the impossibility of direct conversation.

Family, Chosen Family

I met Linye this past May through pure chance. I left a note at a queer art show in Chicago about how the work made me feel: about absence, about searching for each other in spaces not made for us, about the particular loneliness of being queer, Chinese, and here. She saw it, posted it on Chinese social media site Rednote, and I happened to see her post immediately. That note pulled us into each other’s lives. Since then, we have become friends, talking about our shared identity.

None of this is easy or straightforward. She didn’t have conversations with her dad around queerness until she started taking pictures for this project. The camera gave permission to look at him differently. She began photographing him in 2018 documenting him with her son, with herself as an adult, she’s not trying to capture who he was in those old family photos. She’s investigating who he is, who he might have always been underneath the performance of father and husband.

Photography, for her, is a form of sustained attention that conversation cannot quite provide. Through the lens, she can study him without the weight of expectation, without the scripts they’ve both been following. At her opening reception, art also became the bridge for community formation that biology had failed to provide.

When we, as lesbians started talking about family, we realized we were all using the same phrase: 和他们不太熟. When I mentioned this conversation to Linye later, she pushed back. That’s not how she’d describe her relationship with her father. It’s more complicated. He’s attentive to her, even if he didn’t always take her art seriously. His shift came from seeing her commitment to her practice over time.

Now they can talk about queerness, but under a professional guise, detached and critical, through discussion of art and creation. It’s safe to talk about queerness when it’s about artistic process rather than lived experience. She wanted me to see how much care she put into creating this show, care that extends to how she sees him, how she presents him in her work.

Like him, she’s looking for connections and community. She offers her family story on display so that other people can show up and relate. She shows us: here we have a contemporary Chinese queer family. Not quite the kind of queer you might think, but queer in every atom and every interaction. It was hidden, but it was also obvious. It is painful, it is awkward, and like the unframed photos on the wall, it is a work in progress, but it is also true.

Unmovable Forces, Fragile Archives

When I visited the exhibition again, Linye was taking documentation photos. Both of us engaged in different forms of preservation. She told me how these family pictures had been stored in her mother’s childhood home, never displayed in either of their lives. Linye took pictures of the pictures and re-printed them so they would forever look like how she found them: faded old photographs from a happy-presenting family that no longer exists, memories that she cannot remember but that evidently were there nonetheless.

This is one of the interesting things about archiving and preserving: without these pictures being found, Linye would never have noticed the note her dad left for his brother-in-law. She would never have remembered that there might have been happy memories from the first family she grew up in. She would not have had the questions about what family is and how she wants her family to look. She would not have had this show.

The preservation work is urgent because it is so fragile. The forum where her dad published – 天涯社区 “一路同行” – had eighteen years of queer stories, and then it was gone. Unmovable forces. 不可抗力. Personal archives stored in childhood homes, browser histories on family computers, handwritten notes hidden behind photographs – these are the places where queer genealogies survive, or don’t.

Scavenging becomes a method of survival, but also a way of building alternative family structures. The sculpture hanging in the center of Linye’s show is a collaboration between father and daughter who could never directly connect. She chose sentences from his writing that touched her, fragments that helped her understand both him and herself. There, in that sculptural arrangement, they finally have a candid conversation.

She is what state media called 生活西化的女儿 – a daughter living a Westernized life. China News used this phrase to describe Stephanie Hsu’s character in Everything Everywhere All at Once, avoiding the word lesbian. She left. She is now the diaspora. From here, she can see him not as the father who failed to understand her, but as a full human struggling with the same unmovable forces that shaped her own departure.

What does it mean to truly see our parents as full humans? What does it give us, and what does it cost? In an Asian household, being seen, being accepted, being understood, being respected, being loved – these are different things. I do not know what he gets from his daughter, or what he wanted from her. But I know what she offers: acceptance across impossible distances.

We don’t have dads, but here, through fragments, we scavenge what we can. The sculpture hangs in the center of the gallery: pieces of his words, chosen by her hands, a collaboration across silence, a preservation of what would otherwise be lost to unmovable forces. This is what it looks like when queer people create family through art, when absence becomes a form of presence, when scavenging becomes a method of love.

. . .

Linye Jiang presented Scavenger Hunt at 4th Ward Project Space September 14 – October 19, 2025

About the Author: Reo Wang (she/her) is a queer Chinese immigrant, competitive boxer, and PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota, currently based in Chicago. Her research focuses on LGBTQ+ youth, educational contexts, and intersectional experiences among queer people of color. She writes about art as a way to understand the intersections of identity, diaspora, and intergenerational communication. Her friendship with artist Linye Jiang began when she left a note at a queer art show expressing how the work made her feel, a moment that taught her how art creates the connections that traditional structures often fail to provide.