In December 2017, Tempestt Hazel, a founding editor of Sixty Inches From Center, wrote an essay titled “A Case, Cosign, and Roll Call for Women of Color in the Arts.” Rooted in weariness but ending with practical strategies for the inclusion of Women of Color (WoC) in the arts, the article uses the appointment of Julie Rodrigues Widholm as Director and Chief Curator at the DePaul Art Museum as an example of “stealthily building women into the fabric without writing it on the wall, and as if it was the mission all along.” It then goes on to call out the then-upcoming exhibition Out of Easy Reach curated by Allison M. Glenn, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, as another example that promotes this particular method of inclusivity. Glenn’s exhibition combines the forces of arts practitioners and administrators (including Rodrigues Widholm) working primarily across the city of Chicago to present 24 female-identifying Black and Latinx artists who use abstraction “as a tool to explore histories both personal and universal, with a focus in mapping, migration, archives, landscape, vernacular culture, language, and the body.” It is a prime example of what can be achieved when WoC take the lead and their efforts are bolstered by institutional support.

Recently opening across three Chicago venues (the DePaul Art Museum, Gallery 400 at UIC, and the Stony Island Arts Bank), Out of Easy Reach is the brainchild of Glenn and Kellie Romany (Artist Advisor to the exhibition) and was heavily supported from its genesis by activist and collector Dedrea Gray who coordinated individual giving. The catalyst for this expansive project was an “Are you seeing this?” moment of quiet solidarity between WoC as described in Hazel’s essay. Glenn, Romany, and Caroline Kent (an artist included in the show) were at the 2013 Black Artists Retreat watching a reenactment of the 1969 conversation The Black Artist in America: A Symposium when participant Maren Hassinger (also presented in the exhibition) questioned why she and another female participant were sharing a microphone and the male actors each had their own. “[We] just looked at each other and were like, “Oh, this is an interesting moment,” recalled Romany. From there, Romany describes conversations between herself and Glenn (and eventually, Gray) as focusing on the “importance of having a moment” for WoC that evolved into “showing the diversity of what Women of Color do within the framework of abstraction.”

In her article, Hazel calls for the need to follow up on those “side-eye”- inducing experiences through finding ways to “call out these problematic instances” and “demand that the people running things do better from now on.” Glenn, Romany, Gray, and the incredible team they assembled (including Mia Lopez, Julie Rodrigues Widholm, Lorelei Stewart, and Theaster Gates) did one better by claiming the power to run things themselves and established this cross-institutional collaboration centered on elevating the voices of WoC as they explore themes like migration, technology, identity, and politics from a non-body- centric perspective. Though figurative work by artists like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and Jordan Casteel is also very much “having a moment,” Glenn hopes the focus on abstraction builds upon the work of the Black Arts Movement that “pushed towards positive imagery and positive representation” to “allowing for a bit of freedom within that space, allowing for a bit of innovation.” Glenn’s curatorial methodology includes a deep dive into previous examinations of abstraction and Blackness occurring throughout the past 40 years (like April Kingsley’s 1980 exhibition Afro- American Abstraction) as well as the use of Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality and Édouard Glissant’s interpretation of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of the rhizome to construct the theoretical scaffolding supporting the work of the 24 artists presented in Out of Easy Reach.

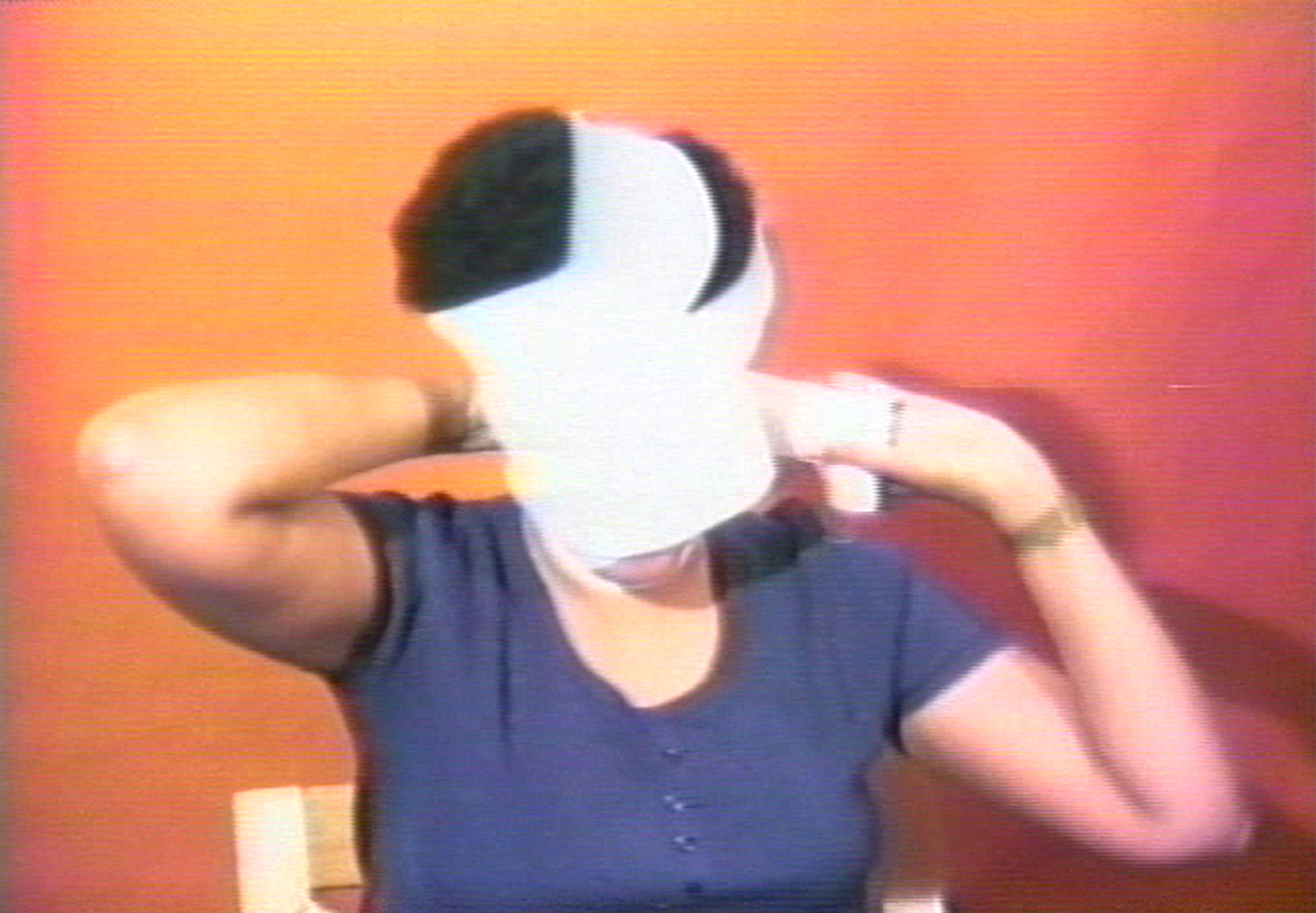

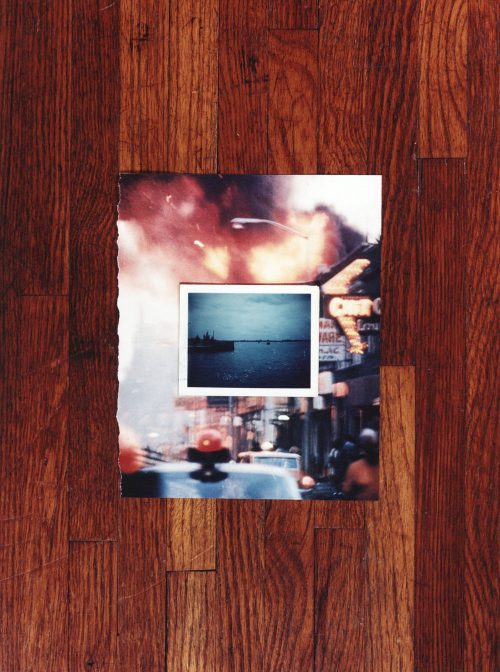

The exhibition’s foundation is formed using seminal pieces like Howardena Pindell’s “Free, White and 21” (1980) as well as work by other established practitioners like Hassinger, Candida Alvarez, and Barbara Chase-Riboud. Starting in 1980 and moving forward, the exhibition includes emerging artists working across the spectrum of practice and experience. The exhibition provides equal attention to the breadth of practice presented, from Romany’s ceramic discs filled with pooled, congealed paint (seemingly birthed rather than sculpted) that are intended for intimate, physical engagement with the viewer to Torkwase Dyson’s works on paper that use the architecture of oppression to form a new language that considers People of Color as they traverse both urban and rural land marred by hostility and systemic racism. Through this heterogeneity of media and topical exploration, Glenn provides the viewer with myriad entry points and fosters opportunities for further investigation. Taking the “moment” that she and her collaborators established, Glenn transfers the responsibility to the audience –scholars, curators, gallerists, etc. – to provide future moments for WoC and other artists deserving of the construction of space for their work.

An unfortunate number of Americans (especially White liberals) expect to reap the benefits of the labor that WoC do to create a more just and equitable society – for example, the 98 percent of Black women that cast their vote for decency in the 2017 Alabama Special Election Senate race. However, like Maya Francis states in her DAME article, “Black women are not here to save you.” While Glenn and her teammates have created a platform for female-identifying Black and Latinx artists that intricately interweaves politics, creative practice, and a theoretical framework deeply engaged with history, what they have actually so generously provided is an opportunity – and not just for WoC or PoC – to take up the labor that will continue to shift the art historical canon towards a multiplicity of voices that more accurately represents who is doing the work and who has been doing the work all along.

Out of Easy Reach is on view at the DePaul Art Museum, Gallery 400 at UIC, and the Stony Island Arts Bank until August 5, 2018. It will then travel to Grunwald Gallery at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana where it will be on view from August 24 to October 4, 2018.

Featured Image: Torkwase Dyson’s hieroglyphic gouache and pen drawings are presented together as Untitled (Hypershape) (2017) and are flanked by Yvette Mayorga’s Monument 4 (2015) and Monument 5 (2015). Mayorga’s seemingly celebratory sculptures critique the pursuit of the American Dream through tempting the viewer with luscious layers of frosting to find plaster underneath. Courtesy of Gallery 400 at UIC.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Annalise Flynn-Taylor is a curator, writer, and art historian based in Chicago. She is the Director of Exhibitions for ART WORKS Projects, a nonprofit organization that uses art to advocate for human rights issues around the world. Her work focuses on practices that expand the definition of art making and intersect with social justice.

Annalise Flynn-Taylor is a curator, writer, and art historian based in Chicago. She is the Director of Exhibitions for ART WORKS Projects, a nonprofit organization that uses art to advocate for human rights issues around the world. Her work focuses on practices that expand the definition of art making and intersect with social justice.