Featured Image: Hal Fischer Photographs: Seriality, Sexuality, Semiotics, installation at Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 2021. Photo by Julia Nucci Kelly. © Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

Good art exhibitions captivate me while I am in the museum itself. It can be the skillfulness of paint or an intriguing concept that engages me while I am in the space. But exceptional exhibitions leave a mark on me as a person so that it becomes impossible to view the world in the same way. This was the case with Krannert Art Museum’s exhibition Hal Fischer Photographs: Seriality, Sexuality, Semiotics, which provided me with the rare opportunity to ask important questions about my queer experience and my own role as an artist.

Though 40 years separate our work, Hal Fischer and I both use photography as an autoethnographic and conceptual art-making tool to express gay identity and sexuality. And while I acknowledge that Fischer’s work from the late 1970s centers on a White, able-bodied, cis-male perspective, his work still has an important legacy for a diverse range of LGBTQIA+ people and artists today.

Hal Fischer’s photographic career blossomed in San Francisco in the 1970s, a post-Stonewall and pre-HIV/AIDS era that has since gained legendary importance within queer communities. It was the era of the Gay Liberation Movement and some of the first openly LGBTQIA+ elected officials were voted into office during this time, including Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to hold office in California in 1978. Hal Fischer was making work in the epicenter of that movement, evident in a photograph of the artist standing next to none other than Harvey Milk himself during the signing for the photobook Gay Semiotics (1977). While walking through the Krannert Art Museum’s retrospective of his work, Hal Fischer Photographs: Seriality, Sexuality, Semiotics, it became clear that it is impossible to view the work today without the collective nostalgia of the “The Gay Seventies” (as is the title of Fischer’s 2019 photobook). For me and many other viewers, this nostalgia is for something that I was never even alive to experience.

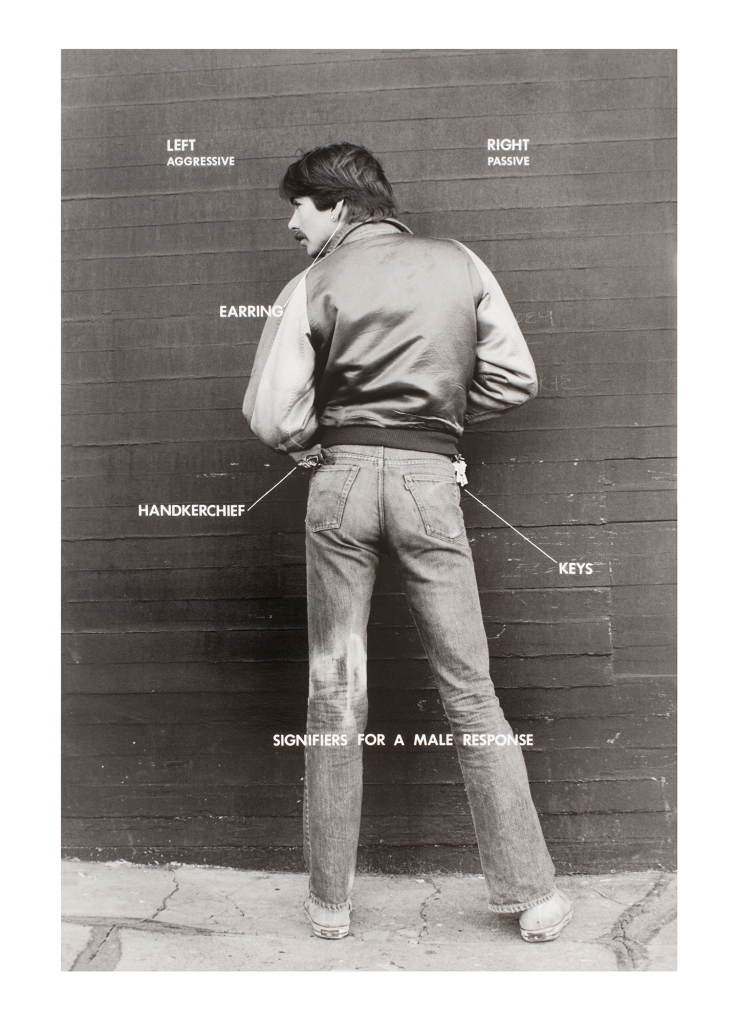

Image description: A black and white photograph of a White man standing outdoors on cement facing a dark brick wall, his head turned to the side in revealing his facial profile. He has long hair and a mustache and wears a bomber jacket, jeans, and canvas sneakers. Small white text within the image in all caps reads: SIGNIFIERS FOR A MALE RESPONSE. Additional text diagrams the image: LEFT AGGRESSIVE, RIGHT PASSIVE. And the figure’s earring, handkerchief, and keys are diagrammed with thin white lines and text.

Fischer’s most iconic and well-known work, Gay Semiotics (1977), depicts the various ways gay men signified their sexual preferences to one another and communicated nonverbally; from everyday clothing to elements of the BDSM community. The work calls attention to the object-ness of the photograph itself by placing text within the image, sometimes providing didactic context and in other instances diagramming the image. As Fischer’s website describes the series, the work is “proud, unapologetic, humorous, and purposefully banal.”

To its viewers over 40 years ago, I imagine that Gay Semiotics was powerfully subversive in its appropriation of the social sciences. It was a much different time in some ways (for instance; homosexuality was considered a diagnosable mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association in the 1970s). In addition to other conceptual readings, the work could have functioned back then as an affirmation of queer desire and ways of life, asserting that gay men deserved to be studied and understood without being pathologized. And while nostalgia saturates our encounter of the work today, it completely avoids seeming melancholy or sentimental. The historicization that inevitably happens whenever we take a photographic image seems intentionally heightened in the work. It is almost as if the work was made with our present-day nostalgia in mind, evident in visual cues taken from textbook images and the work of August Sander.

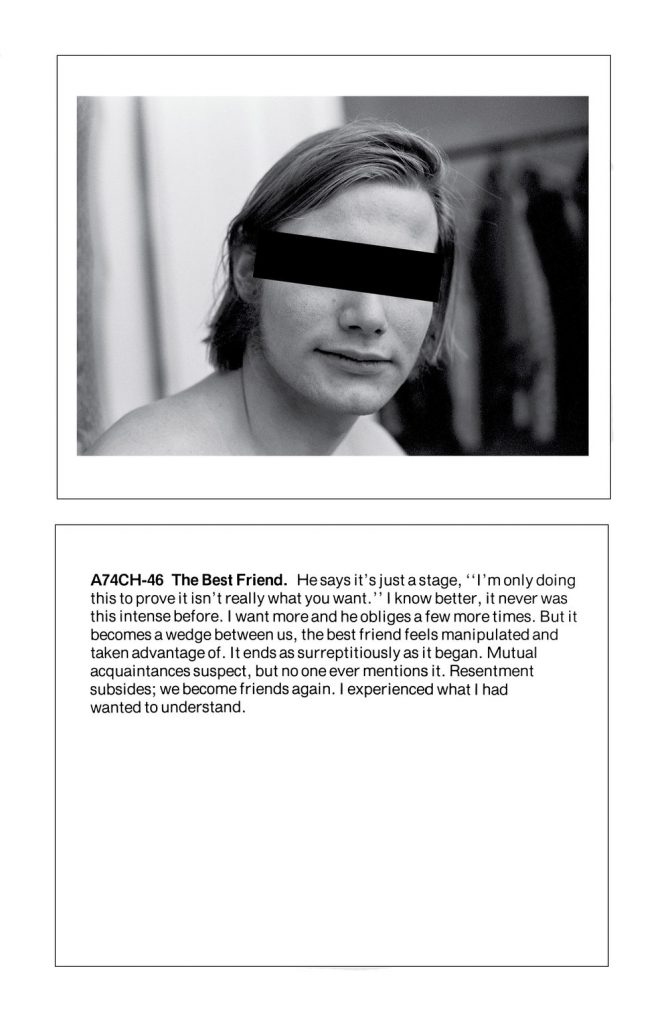

But it wasn’t Gay Semiotics that I saw the first time I viewed his work in person years ago, but his series Boy-Friends (1979). Ten framed black-and-white portraits of men accompany ten blocks of text underneath. Each block of text describes the relationship which Hal Fischer had with each of these men. In the corresponding portrait above, a black censorship bar is superimposed over their eyes. While Gay Semiotics plays on the impersonal scholarly distance of ethnographic research, Boy-Friends is undeniably deeply personal. The interactions described in the text range from casual one-night-stands, intimate friendships, and tumultuous romances.

Even though Boy-Friends describe interactions decades ago, I immediately identify with the transient nature of these gay interactions, as so many of these stories mirror my own even 40 years later. Now, just as back then, discovering one’s LGBTQIA+ identity can be freeing by no longer being bound by traditional heteronormative notions of family, relationships, or sex. But as a gay man, I’ve struggled with hetero-masculine societal expectations that lead many men I’ve interacted with to be closeted. In reading the text for images like A Traveler from Boston, The Punk Poet, and especially The Best Friend, I connect with the joy that I’ve received from similar ephemeral gay interactions and simultaneously feel sadness for those interactions which ended too soon. In this way, Boy-Friends is historically distant but also recognizably present.

In thin black outlines, two equal-sized boxes are placed vertically. Within the top box, there is a black and white photographic portrait of a young White man with long hair. His eyes are censored with a black bar. In the bottom box, the text reads: A74CH-46 The Best Friend. He says it’s just a stage, “I’m only doing this to prove it isn’t really what you want.” I know better, it never was this intense before. I want more and he obliges a few more times. But it becomes a wedge between us, the best friend feels manipulated and taken advantage of. It ends as surreptitiously as it began. Mutual acquaintances suspect, but no one ever mentions it. Resentment subsides; we become friends again. I experienced what I had wanted to understand.

When I first saw Hal Fischer’s Boy-Friends in 2019, the work brought me to tears. I didn’t cry because of sadness, it was the honest simplicity of the text which made my experiences feel shared and seen. Several of the photographs and text made me recall men from my experiences who I had almost forgotten about, through will or neglect. I couldn’t help but imagine what some of them would look like as photographs on this wall. While I was viewing these photographs in the exhibition, I overheard the artist explain the meaning of the alphanumeric code before each title (the second two numbers represent the year, and the following two letters indicate the location). The letters “CH” in the first image stand for Champaign, Illinois, where I’ve also met so many men, who come and go as they do in any college town.

In this exhibition, Hal Fischer’s largely unexhibited and unknown early work is put in context with his most celebrated photographs from 1977-1979. This inclusion is something that the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Krannert Art Museum is uniquely positioned to do, being where Fischer received a BFA in 1973. Although not all of these early works are captivating by themselves, they demonstrate years of developing the experimentation, formal skills, and interests that would later become his most notable work. The inclusion of his early photographs fills a large hole in the scholarship of his work and also reveals several remarkable gems in the process. As an artist, I found the early work to be an important reminder that I don’t need to be doing my best work at any given moment, as any work that I do will inform future pursuits. This aspect of the exhibition is extremely important for artists, and especially undergraduate viewers in this university museum setting. In fact, Fischer quipped “most photographers only have 3 good years.”

Fischer stopped making artwork around 1980 when he became more involved in writing and museum work. Afterward, his work remained largely unexhibited until 2011 when they were included in Under the Big Black Sun: California Art, 1974-81 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Since then, his work has been exhibited at MoMA, Fotomuseum Winterthur, and Art Basel, and has been included in an equally impressive list of group exhibitions internationally.

However, this exhibition is different. For the first time, scholars are paying close attention to his photographs, placing them within historical contexts and analyzing them in ways they’ve never been. I had the pleasure of attending a symposium that took place all day on Saturday, November 6th, 2021 organized by Dr. Tim Dean, James M. Benson Professor in English at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and the curator of the exhibition.

While discussing the exhibition with Tim Dean, it occurred to me how perfectly suited he is to curate this exhibition. Dean is most known for his book Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking (2009), which explores the taboo subject of unprotected gay sex. A common thread I saw between Dean and Fischer’s photographs is that both of their work exposes insider knowledge of gay male sexual experiences that have previously been guarded and closed off from larger society. It is something that I have also done with my work Webcam Aesthetics (2019-2021) which focuses on queer erotic webcamming. I naturally started to wonder why it is so important to talk about sexual experiences, given the risk often involved in doing so, to careers, communities, and those who may want to weaponize any information given about sexual minorities against them. Dean acknowledged this sentiment. He said, “I was writing about risk, but the very act of writing and publishing it had various kinds of risks involved.” But overall, he believes those risks are worth it:

“I think all of us benefit from the circulation of sexual knowledge, so that people have a sense that there’s not just one way to have a sex life. It is not just about getting married and reproducing, there is in fact a whole range of ways one might pursue and cultivate one’s sexuality.”

Tim Dean

The resurgence and renewed interest in Fischer’s work is taking place in a time that symposium speaker Peter Rehberg, Head of Collections and Archive at the Schwules Museum in Berlin, called the PrEP Generation, a return to the 1970s in terms of the queer communities’ sexual promiscuity and exploration. Additionally, the last decade has also seen LGBTQIA+ communities flourish online, even while these communities are simultaneously censored, harassed, and monetized. Many of these online communities are specifically dedicated to reclaiming and connecting with our histories, as evident in a slew of Instagram pages I follow such as @LesbianHerstoryArchives, @LGBT_History, @TheAidsMemorial, @Visual_AIDS, and @LeatherArchives. All this has made fertile ground for Hal Fischer’s comeback over the past ten years.

It was impressive and empowering to see the diversity of people engaging with Fischer’s work in a personal way. Most notable was Jacques J Rancourt’s beautiful short poem Crossed Signals, which was one of the winners of a competition seeking poetry that responds to Hal Fischer’s work. In its several short minutes, the poem brought tears to my eyes. Both this poem and another by Jeanette Lynes were printed as broadsides on a large square paper in the form of a handkerchief by Meanwhile… Letterpress, “a trans and queer owned and operated letterpress who seeks to collaboratively resist erasure through print culture” (from their Instagram page @meanwhileletterpress).

During the symposium, Maryam Kashani, an Assistant Professor of Asian American Studies at UIUC and also a Visiting Fellow at the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration, offered an important perspective as a filmmaker and anthropologist from the San Francisco Bay Area. Because of her familiarity with the Bay Area and its marginal communities, Kashani said she sees a “home for me, perhaps that was not made for me.” For Kashani, the element of humor in Fischer’s work undermines his role as an ethnographer and allows for her to enter the work even if she is excluded from it. Humor was also a theme that was touched on in the symposium by Terri Weissman, Associate Professor and Chair of Art History at UIUC. She was able to pick up on a Jewish sensibility to Fischer’s humor, which she believes is a reason why the work avoids seeming melancholy or sentimental even though evoking the nostalgia of the 70s before the HIV/AIDS crisis was detected.

I had such an affinity for Boy-Friends, that when the Krannert Art Museum hosted an event on Halloween of 2019, I dressed up inspired by the series complete with a black bar across my eyes. But I wasn’t the only one who felt a strong connection to his work. Without coordinating, one of my good friends in the Studio MFA program also happened to be dressed up and inspired by Gay Semiotics. Ultimately, Fischer’s work is about community, but it also creates community. As Tim Dean said in an interview, Hal Fischer’s work “documents a moment, but it is completely translatable to our present moment. You can embrace it, you can inhabit it, you can play on it today. The work has its ongoing life, and the way we think about it and talk about it now is a part of its ongoing life.”

Jake Foster (he, him) is a visual artist using photography, drawing, sculpture, performance, and net art to reflect on physical and digital spaces of queer sexual intimacy. Foster received an MFA in Studio Art at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2021, and a BA in Art at Rutgers University-Camden in 2017. He has had solo exhibitions at the Noyes Museum of Art at Stockton University and at The Delaware Contemporary in Wilmington, Delaware.