The slope of a hip, the swell of a breast, the sinewy muscles underneath the flesh; the human body is a form of art in and of itself. This is a sentiment that resonates across cultures, evidenced in how often the nude figure appears throughout history in art and literature. Painterly exploration of the human form is familiar terrain, but in How Far Between and Back at Monique Meloche Gallery, Brittney Leeanne Williams eschews references to traditional depictions (i.e. eurocentric, allegorical, white) choosing instead to push past the limits of the human body and portray them as fraught, abstracted, and entangled, grounding them firmly in the surreal contemporary.

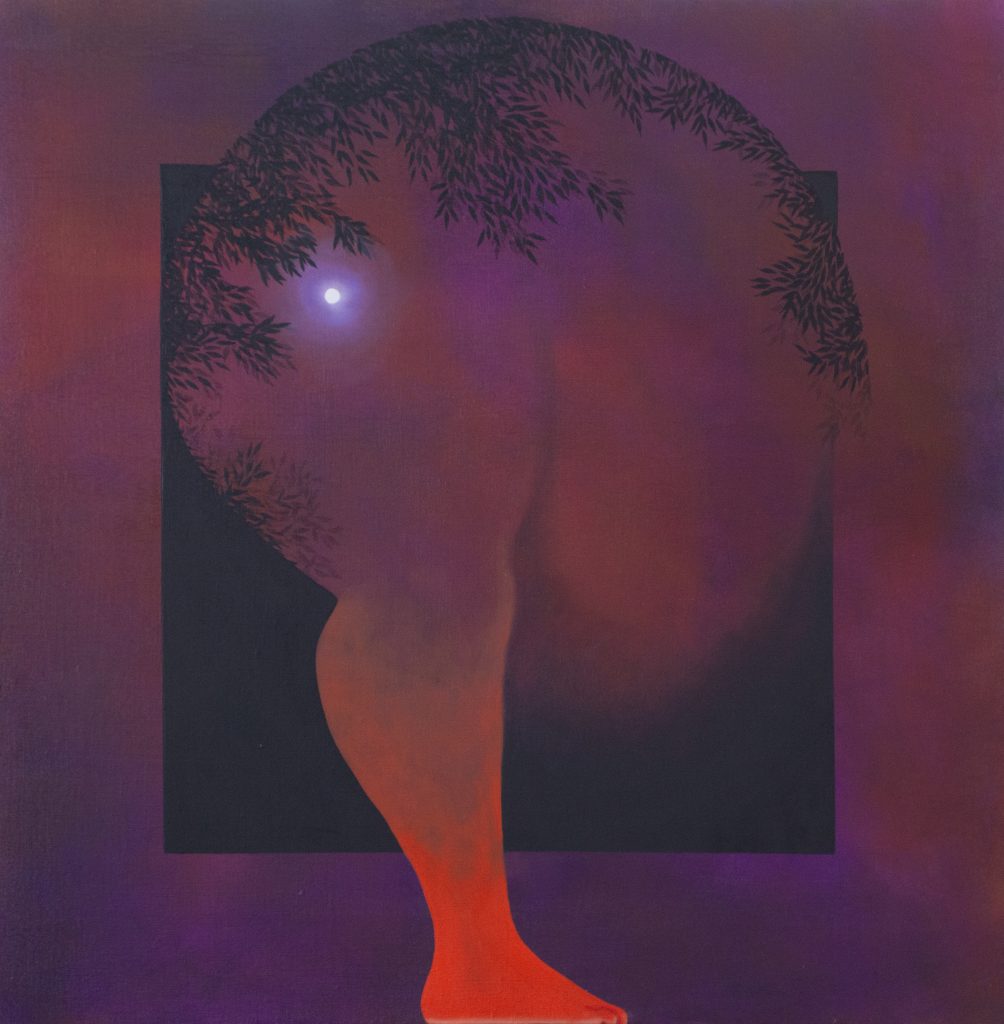

The show of seven works is a study of a range of bodies and their various parts set against hot landscapes and sharp geometric framing. Surrounded by tropical foliage, William’s female figures are vastly different from the classical depiction of the nude female form. With their generous rolls of flesh, William’s subjects more closely align with the bodies of everyday women. The women in her paintings carry a sense of heft that contradicts the westernized standard of beauty idealized in our visual media. She further distances her subjects from western tradition by not depicting them as leisurely or reclined, but instead as yielding to gravity, or perhaps some other unknown force that tugs them downward. Williams’ subjects are slouching, collapsed figures, and contorted tense muscular forms. The bodies on the canvas aren’t always obvious; Williams breaks them down so thoroughly that errant body parts appear across all of the works. Sometimes the form is lost among the other details, leaving you searching for the recognizable curvatures of flesh. Other times the bodies fold into themselves, expanding and filling the canvas. Her red-colored subjects are all unidentified, headless and faceless, mashed together and transformed. In some instances, they resemble slabs of skin pulled taut over muscle and fat, in others, they appear like plumes of searing red smoke or a flutter of red leaves. About the show, Williams writes simply, “each [piece] represents a multitude of women: the artist, the mother, the daughter.”

Drawing upon her personal experience, the artist pays homage to her childhood in southern California with the citrus fruit and barren Martian-like landscapes in her works. The hot colors used throughout the exhibition create a warmth that emanates from the paintings; a dark heat that recalls the kind of summer days when the setting sun hangs in the air long into the evening, leaving a lingering heat all night. I happened to see the show on a blazing 80 degrees day in late April, a rarity in Chicago during the spring. The high temperatures coupled with the burning reds, oranges, and yellows in the paintings, immediately transported me to summer, and all at once, the show felt almost too hot. Pacing the windowless room, moving from piece to piece, examining each work, and pulling from it as much detail as possible left me with the dizzying sensation that I was wandering through someone else’s fever dream.

People who think about art will always look for allusions to the Black experience in art by Black artists. Rightly so, because the context in which art is created is just as important as what its subject matter depicts. In the context of art history, brown figurative art, nude or otherwise, has not been afforded the same space as their white counterparts. But does this mean that Black figurative artists are required to speak to Blackness plainly and directly in their work? Brittney Leeanne Williams is a Black woman and yet the Blackness of her subjects here is not explicit. In some of her similar works [not included in the show], she explores Blackness with melanated skin and textured hair. However, in How Far Between and Back, without heads or faces, she removes ways of defining ethnic characteristics. And in place of brown skin, Williams colors her figures a scorching red. In some cases, specific details do allude to their potential Blackness. I noted the soles of their feet and how they’re a lighter color than the skin of the leg. If not a deliberate nod to Blackness by the artist, then this is the kind of detail that people like me (a Black person who looks for Blackness everywhere and thinks about art) are inclined to latch onto. But is that sliver of representation enough? It’s hard to say what enough would be because it implies that, at a certain point, there is such a thing as too much Blackness and also not enough Blackness. Ultimately, it depends on the audience and their expectations, and Williams leaves that undefined. Was that enough for my taste, no–but that’s just me.

After viewing the show, I was left not unsettled but questioning. Who are these subjects? What are these bodies trying to tell me? The women on the canvases are weighed down, collapsed. I turned to my own history and I see my late grandmother in these forms. Her body like the ones in the paintings bent over doubled in a sweltering Texas kitchen, stooped with age, but still serving her family up until the day she died. I see women I know and women I don’t know in these forms and I worry. I’m reminded that in a patriarchal society–one that demands sacrifice and subservience–womanhood, specifically Black womanhood, is often defined by what we’re able to endure. Our bodies are capable of enduring so much, and yet that doesn’t mean it doesn’t weigh us down and take its toll on us. Collectively we have been dealing with a profound amount of trauma over the last year, and beyond. We’re all experiencing burnout at extraordinary levels. These tired and conflicted forms are reminders that our bodies will give out from under us if we’re not careful. We need rest.

Brittney Leanne Williams: How Far Between and Back is on view at Monique Meloche Gallery from April 24 through June 12, 2021.

Featured image: An installation view of Brittney Leanne Williams: How Far Between and Back. Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery.

Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is an arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago, IL.