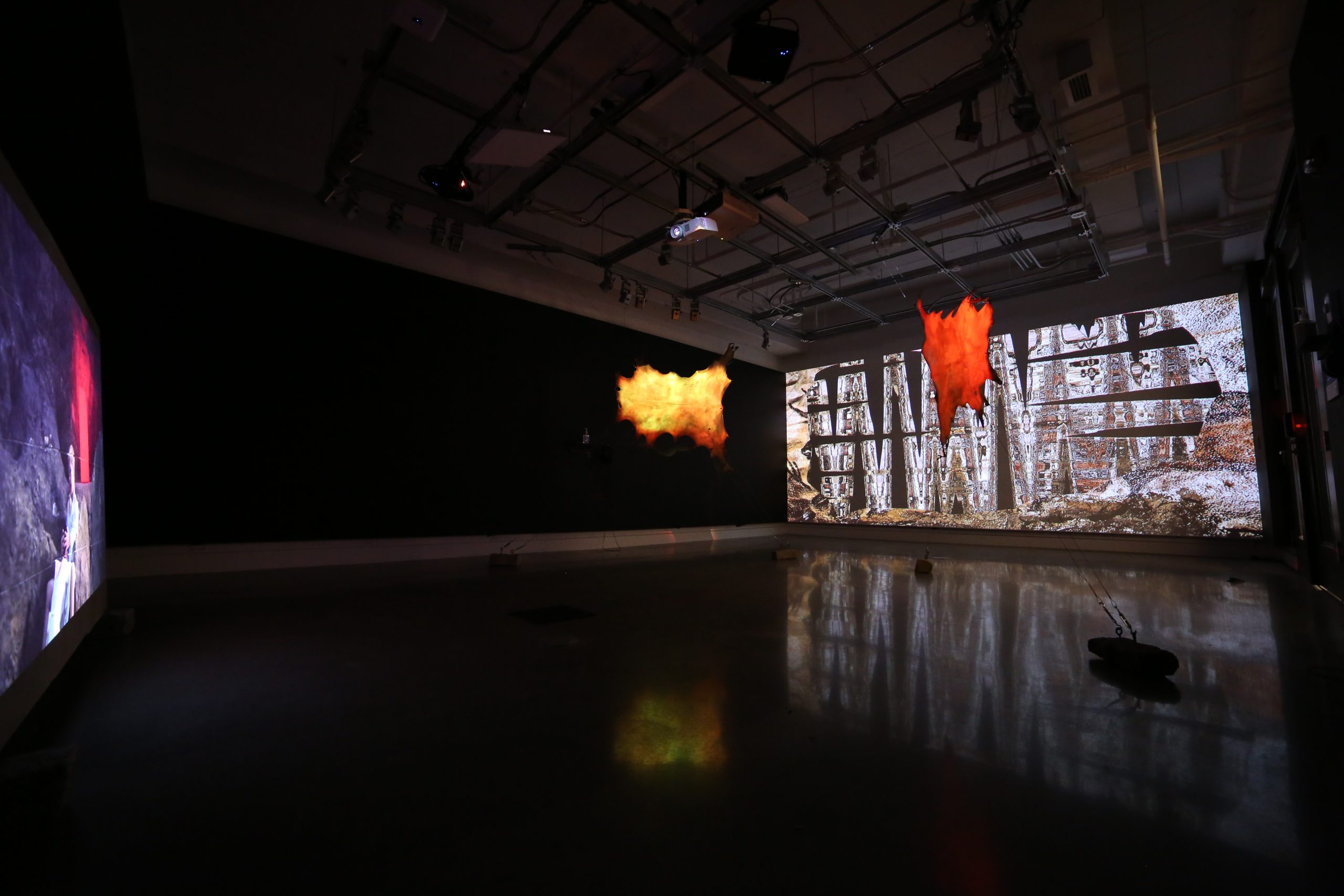

Featured Image: Exhibition view of a dark gallery in the center hangs two stretched animal pelts. A large image is projected on the back wall. Courtesy of Parinda Mai.

In elementary school, I had a teacher that could best be described as a born storyteller. Wide-eyed and utterly transfixed, I would watch the words fall out of her mouth as she shared story after story with our class. Drawing from various sources, her personal history, Greek mythology, the Old Testament, she would find a way to beautifully string her words together and retell an anecdote that would find a permanent home in my mind. I can recall some of the stories she shared with such rich clarity, I nearly forget the scene she painted didn’t happen to me. There are larger myths that are shared across cultures widely enough that they become a part of our collective memory. Humankind relies on storytelling to connect us with and inform us of our past. Whether it’s detailed recollections of groundbreaking historical events, or a grandmother passing on ancestral wisdom, storytelling shapes human history. Artist Parinda Mai investigates the Buddhist myth-folktale, Twelve Sisters, in the exhibition, 12 Kalpas from Terrestrial to Celestial and Everywhere in Between, at SITE 280 Gallery. If a perfectly executed resharing of a myth is captivating enough to hold attention and thematically powerful enough to burn a lasting image in a listener’s brain, then Mai’s exhibition is an exemplary visual investigation of such discourse. The exhibition is undeniably hypnotic in the combination of vivid digital projection, alluring moving images, and surprising mixed-media sculptural elements. 12 Kalpas from Terrestrial to Celestial and Everywhere in Between grapples with complex topics like gender identity and our relationship to our environment through the investigation of Twelve Sisters.

Upon entering the room, the viewer is immediately engulfed by the first digital projection, Dislocated History. Spanning the height and width of the gallery wall, the image created is reminiscent of an autopsy of a moth photographed through a kaleidoscope dripping with abstractions of gold and black. The projection is richly layered with distorted scraps of images. Close-up, nearly recognizable elements such as the jutting texture of a rock bed appear in the background. Stepping away, the projected image becomes cohesive through Mai’s smart use of pattern. Relying on the shape, color, and texture of the abstracted elements to create a pattern, a transfixing full image is the result. The title, Dislocated History, effectively encapsulates two prevalent topics in the work. “Dislocation” is a tricky concept to assign imagery to, but is successfully demonstrated by the act of piecing together the distorted elements that make up this projection. It’s human nature to try and make sense of visual material, and this projection, though abstract, provides just enough information to encourage the viewer to fill in the gaps. Like trying to remember the details of your childhood home, desperate to complete the image in your head, you will unavoidably embellish the fuzzy parts. The familiarity of the images in this piece feels like it’s a location the viewer should recognize, resulting in the frustrating inability to fully locate it. The other theme true to the title of this work is “history.” The projected image is similar to a geological diagram found in a textbook, or a warped archaic map. It is easy to get lost in the dichotomy of mentally placing your microscopic self into the map, or looking at the image as a landscape from deep within your memory.

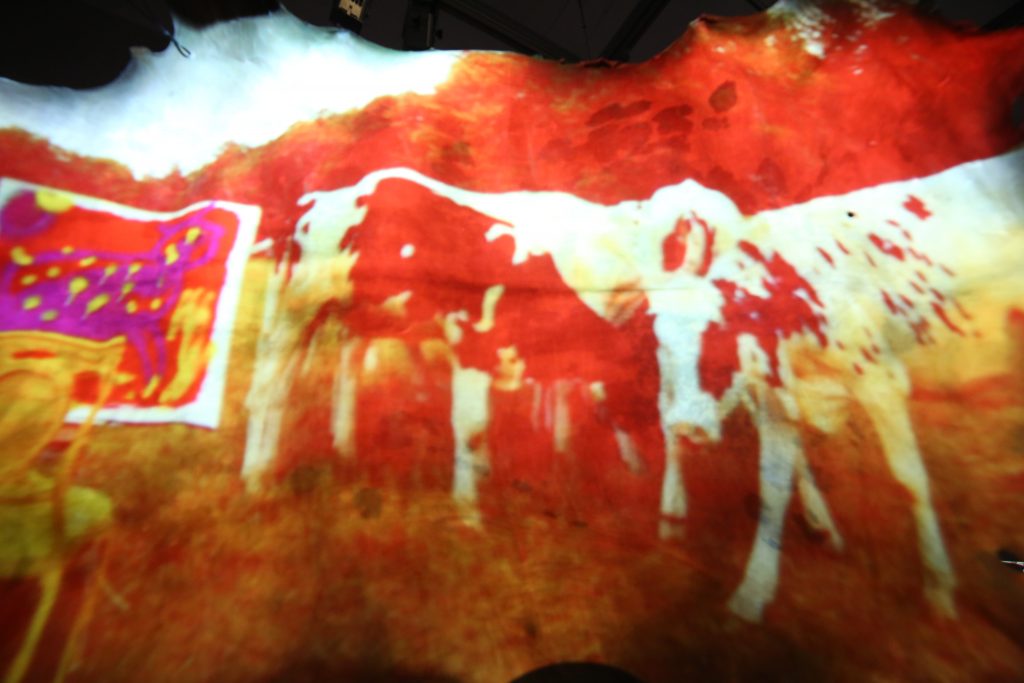

Gleefully Yours consists of a two-channel moving image projected onto cowhides. Stretched expansively by a subtle apparatus of wire, an illusion of floating, pancake thin animal remains explode from the surrounding dark unlit gallery space. The unfolding moving image of vibrating reds and yellows traps the viewer in place. Fascinating and increasingly unpredictable images tick by one after another, creating an inescapable desire to see what will appear next. A notable scene reveals a leaf-covered ground with a flickering fire, abstracted by the shape of a hand resting amongst the flame. The image begins to slowly recede towards a central vanishing point, as though the camera lens is zooming out. This creates a striking and disconcerted illusion of freefalling forcefully into the frame, like watching an ant succumb to quicksand. The effect of this illusion encourages the viewer to look outside of the moving image in order to reorient themselves.

In a truly pivotal frame, a herd of cows appears, casually grazing amongst themselves. The moment forces the viewer to consider the fact that this image is projected on the remains of one of these creatures. Mai’s ability to strategically reinforce notions of mortality, while not allowing death to become the weighted force of the exhibition, is a delicate and impressive feat. While looking at these living, hopeful, unknowing cows reflected on the fibers of a dead cow’s hide, sadness surrounding death doesn’t become the prominent thought. Rather, a more complex conversation about our relationship to nature, and nature’s relationship to technology is ignited. Even a staunch meat-eater can experience this visceral response, this moment is not propagandic, but rather an invitation to join Mai in an exploration and assuage with these complexities.

On the wall opposite of Dislocated History, sits a moving image piece on a screen propped up by two rocks. The video, A Beginning of Beginning, follows two people, dressed in crisp white linens, over the course of a silent journey. The duo stroll through a sharp, rocky landscape, periodically stopping to engage in the presence of one another, either in gentle touches, quick glances, or breaking from their walk to engage in sexual acts. For the majority of the piece, their faces reveal very little, as they remain stoic with each step. Towards the middle of the film, two figures are seen resting on a flat patch of soft, sand-colored ground. The figure on the right sits on their knees, takes off their top, and stoically remains in this statuesque position for several minutes. The figure on the left stretches out and begins to pantomime masturbation on their implied but unpresent penis. This moment reveals a stark contrast between the two figures. The figure on the right, either unallowed or uninterested in showing emotion, remains an object to the viewer’s gaze. The figure on the left is uninhibited by the viewer, completely enveloped in their own satisfaction. The gender binary is grappled within this dichotomy, though there are many ways to view exactly how. The figure on the right could be uninterested in the sexuality being introduced by the other figure, they could be finding their own satisfaction in their role as the onlooker, or they could be completely unphased by sexuality altogether. The exceptional performance by the left figure easily captivates the viewer, leaving the right figure unperceived. Every emotion that crosses the left figure’s mind is perceivable: frustration, satisfaction, exhaustion. The opposite is true for the figure on the right. It is the lack of clarity in the right figure’s emotions that introduces the larger conversation of gender, the binary, and sexuality.

Though there are only three pieces included in this exhibition, it is near impossible not to spend a significant amount of time within the space. A cross between an alternate reality and a familiar memory, 12 Kalpas from Terrestrial to Celestial and Everywhere in Between is spellbinding. Stepping between pieces is like sifting through the caverns of memory, bathing in the combination of comfortable familiarity and unnerving uncertainty. Mai’s relationship to the myth-folklore, Twelve Sisters, is felt through the apparent tender consideration in each decision made. The complex concepts of gender identity, the human relationship to nature, personal histories, and memory are deeply felt, considered, investigated, but never solved. 12 Kalpas from Terrestrial to Celestial and Everywhere in Between leaves the viewer to chew on these concepts well outside of the constraints of the gallery space. As I left, I felt l as if I was in a trance, utterly absorbed in the world Mai created. The hypnotizing, multifaceted pieces in the exhibition left me with a familiar feeling as if I just heard another engrossing story from my teacher. Storytelling encourages humankind to look to those that have walked before us, consider their experiences, and build upon them. These stories can shift in their shape, alter their content, and one day grow into something unexpected, like an unforgettable art exhibition.

Ally Fouts is an artist, designer, and writer living in Chicago. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Art, Media, and Design from DePaul University. More information surrounding her artistic practice can be found on her website.