Children’s laughter bounced off the walls of the Co-Prosperity Sphere gallery as a group of about 40 people gathered for a “Day of Solidarity” on August 4 in support of an upcoming national prison strike. All afternoon, people filtered in and out as organizers from Milwaukee to Oaxaca spoke, supporting organizations sold t-shirts and zines to fund strikers’ commissary, volunteers at a letter-writing station matched attendees with incarcerated pen pals, and musicians performed.

The strike, set to begin August 21 and end September 9, was called for by Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, an incarcerated group of prisoner rights advocates. After a riot at Lee Correctional Facility in South Carolina left seven inmates dead in April of this year, the group decided that they could no longer wait for the ideal conditions for a strike, as these kinds of tragedies would keep happening unless prisoners worked together. In an August 11 statement, the group wrote,

“Prisoners understand they are being treated as animals. We know that our conditions are causing physical harm and deaths that could be avoided if prison policy makers actually gave a damn. Prisons in America are a warzone. Every day prisoners are harmed due to conditions of confinement.”

People in prisons, jails, and detention centers across the country are being encouraged to protest unsafe conditions and human rights violations by refusing to work, going on hunger strike, boycotting commissary and participating in sit-ins.

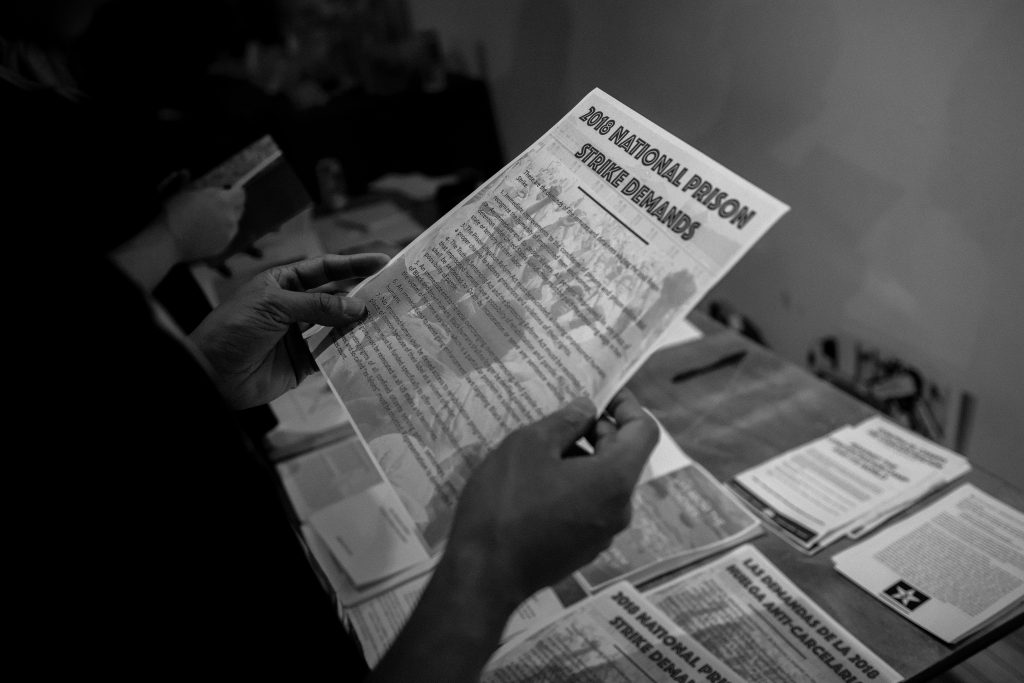

With this call, organizers on the inside put out something unprecedented: a list of national demands. “In the past, people were hesitant to put out national demands, because we know that every prisoner’s situation is different, and the difference from state to state and facility to facility is so broad,” explained Ben Turk, an organizer with A Fire Inside and Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC).

Their demands are:

- Immediate improvements to the conditions of prisons and prison policies that recognize the humanity of imprisoned men and women.

- An immediate end to prison slavery. All persons imprisoned in any place of detention under United States jurisdiction must be paid the prevailing wage in their state or territory for their labor.

- The Prison Litigation Reform Act must be rescinded, allowing imprisoned humans a proper channel to address grievances and violations of their rights.

- The Truth in Sentencing Act and the Sentencing Reform Act must be rescinded so that imprisoned humans have a possibility of rehabilitation and parole. No human shall be sentenced to Death by Incarceration or serve any sentence without the possibility of parole.

- An immediate end to the racial overcharging, over-sentencing, and parole denials of Black and brown humans. Black humans shall no longer be denied parole because the victim of the crime was white, which is a particular problem in southern states.

- An immediate end to racist gang enhancement laws targeting Black and brown humans.

- No imprisoned human shall be denied access to rehabilitation programs at their place of detention because of their label as a violent offender.

- State prisons must be funded specifically to offer more rehabilitation services.

- Pell grants must be reinstated in all US states and territories.

- The voting rights of all confined citizens serving prison sentences, pretrial detainees, and so-called “ex-felons” must be counted. Representation is demanded. All voices count.

The demands speak for themselves: Some are meant to address the well-documented racial disparities in the prison system, where black Americans are incarcerated at a rate five times higher than whites. Others deal with human rights and citizenship issues like voting rights. Central to this conversation is prison labor, a billion dollar industry that props up the prison system. Private companies enlist prison labor to produce items such as military accessories, braille textbooks and dental crowns. In California, more than 2,000 inmates, including over 58 juveniles, are fighting wildfires for $1 an hour. But the bulk of prison labor is funneled back into the prison itself. The mandatory work of inmate orderlies, clerks, plumbers, painters and groundskeepers creates a closed circuit where the prison’s existence is dependent on the conditions it creates.

Parita Shah, one of the event organizers and a Chicago General Defense Committee member, mentioned that the demand to rescind the Prison Litigation Reform Act is particularly important. The 1996 law makes it more difficult for prisoners to file lawsuits in federal court, because they must first exhaust all available prison administration grievance procedures. “Why would we not want prisoners to be able to complain if something bad is going on?” said Shah.

In conversation with organizers, two years come up again and again: 2010 and 2016, when the most widespread prison uprisings in recent memory took place. In 2010, communicating with smuggled cellphones, inmates across six prisons in Georgia launched a coordinated work stoppage, calling for better conditions and wages for their labor. After six days, the strike was called off amid reports of retaliation from administrators in the form of pepper spray, tear gas, and brutal beatings.

On September 9, 2016, the 45th anniversary of the 1971 Attica Uprising, dissent came to a head once again. The Free Alabama Movement, an inmates rights group, and IWOC, an initiative of the Industrial Workers of the World, coordinated the largest-ever prison strike in the U.S. An estimated 24,000-72,000 prisoners were involved in 24 states. Their objectives were to restore prisoners’ human rights, and to draw attention to the 13th amendment clause that abolished slavery—except for as punishment for a crime. The strike lasted several weeks.

The current call to action is heavy with these histories–the predetermined start and end dates commemorate, on August 21, the anniversary of black revolutionary and prison activist George Jackson’s murder, and the subsequent Attica Uprising on September 9.

Resistance is actually possible. The holds are beginning to slip away.

-George Jackson (1970)

Some of the key figures from earlier strikes are already facing what organizers say is a coordinated campaign of repression. Imam Siddique Abdullah Hasan, a 2016 organizer incarcerated in Ohio, just ended a week and a half long hunger strike after prison administrators took away his phone access to prevent him from being a spokesperson for the strike. Kevin “Rashid” Johnson, a prolific artist, New Afrikan Black Panther Party member, and IWOC organizer, is being kept in solitary confinement. Johnson was charged for “inciting a riot” January 10 after publishing an article about the Operation PUSH strikes in Florida the day before.

Though participating in this week’s strike comes with serious risks, so does everyday life when you’re incarcerated–talking back to a guard or standing up for yourself can also have consequences. “Prisoners are always resisting,” said Turk. “When there’s a call for a national strike, and a coordinated effort so that each individual’s participation can be part of a larger thing, then it’s more likely to be successful than if they take action by themselves.”

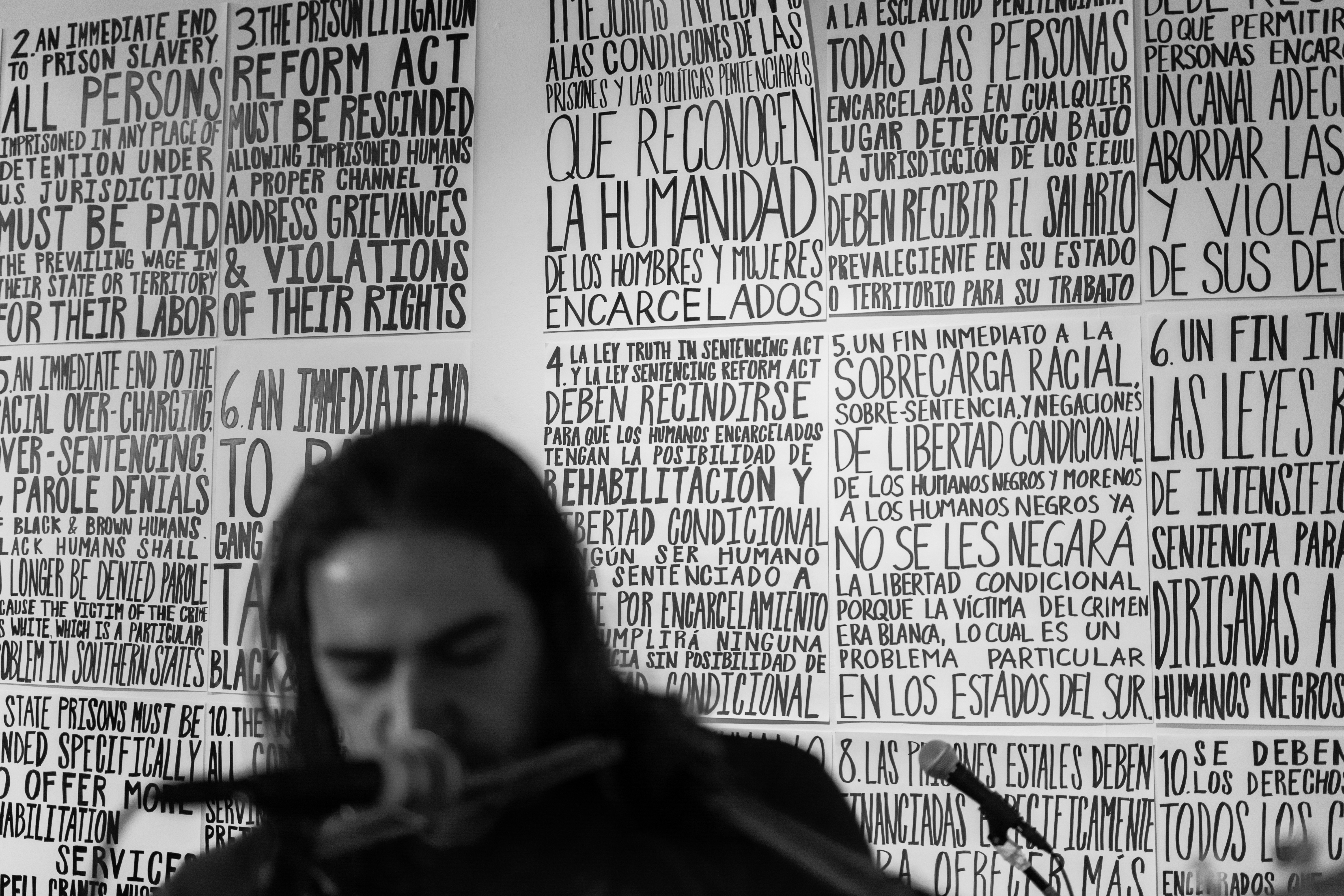

At Co-Prosperity Sphere, clipboards with yellow steno pad paper crammed with messages of support addressed to Hasan, Johnson, and others were passed around like holiday cards. The informal semicircle of chairs was arranged around a display of posters with the strike’s national demands written in block print in English and Spanish.

Coordinating actions across the inside/outside barrier and administration-mediated communication is an ongoing challenge. Letters and phone calls that mention the strike explicitly may be censored, or put the prisoner at risk for retaliation. For the last two weeks, organizers have held demonstrations in front of Cook County Jail, the Metropolitan Correctional Center, and the Juvenile Detention Center in attempts to get the word to people inside.

One of the most concrete ways that people support prisoners in the U.S. is through letter writing and forming pen pal relationships. For Turk, having a personal connection to and winning battles with people on the inside was a ruptural experience that altered the way he engaged with the world. Letters can also help prevent retaliation towards the recipient. “Letting prison administration know that people on the outside are watching is really important,” said Shah.

Organizers are hopeful that if enough people inside learn about and participate in the strike, the administration will be put in a position where they will have no choice but to concede to their demands. “This has the capacity to bankrupt not just correctional department budgets, but state budgets,” Turk said at the event.

“An interesting thing about the demands, generally, is that they are not specific demands that can be satisfied by prison administration,” said Turk. “Wardens can’t do these things–these are calls for changes on a national level, and national legislatures, and society in general. We live in a prison society, and these demands are calling for a change to that.”

_

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: Zach Nelson, Bad Water Sound, performs during the Day of Solidarity for the National Prison Strike at Co-Prosperity Sphere. Behind the musician, posters listing the strike’s demands hang in Spanish and English. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo.

Jordan Sarti is a writer and journalist in Chicago. Her writing has appeared in In These Times, HYSTERIA, Temporary Art Review and Slutist. Right now, she is thinking about body politics, carceral capitalism, and plants. In her spare time she invents increasingly intricate ways to rest.