Pharmacy receipts leave behind a record of bodily care. When Katz Tepper stumbled across the artist Roger Brown’s receipts for HIV medications floating amidst his sketchbooks, these interpolations, more so than Brown’s art, were the punctum. For Tepper, a queer and chronically ill artist, the receipts lingered as material traces of care for the artist’s body falling apart, providing context for the work, but also contact with the artist’s life as lived: “The pharmacy receipts in the sketchbooks are an extension of a body’s boundlessness, and the sketches themselves: bodily deposits.”

An extension of boundlessness: like the thin scrap of paper I hold in my hand after picking up another vial of estrogen, my body is fragile too, a relational archive of evolving needs. I mean this materially and not abstractly; impressions of time and place mark my body as vulnerable and contingent on care. So that the paper trail and paraphernalia of a personal medical record, like doctor’s notes, patient journals, and scrips, outline a narrative account of the self as dependent. The role of the patient—who is expected to remain acceptant and, yes, patient, even when tested and beset by Kafkaesque delays and difficulties—is hardly passive. Yet the patient is too rarely regarded as authoritative, least of all as an author in an account of emergency and emergence.

A crip perspective recenters the patient as an expert by necessity of their own body and condition. Look to the example of ACT UP, a coalition of AIDS activists who took matters into their own hands in the face of neglect, learning the ins and outs of the epidemic in real-time and pushing back on the slow-acting FDA and pharmaceutical companies in an effort to keep themselves or loved ones alive. The urgency of survival pushed against a building sense of powerlessness in waiting for care while wading in medical bills, or navigating the insurance runaround. Some of us cannot afford to be patient; we’re on a different timeline.

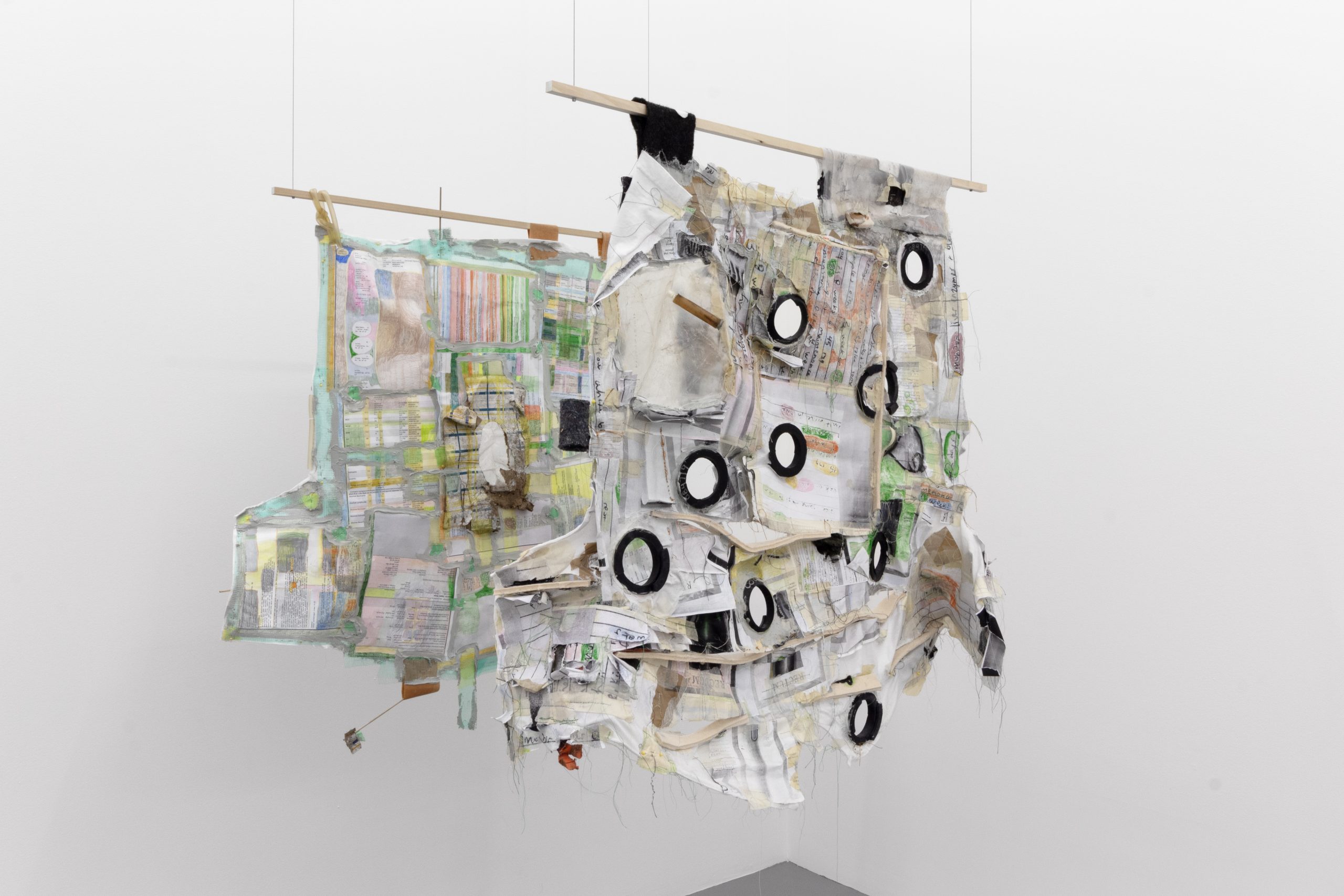

Pharmacy Receipts, Tepper’s solo show at Prairie gallery in Chicago, is expansive and ecological in how it draws on a diversity of materials to leave a record of trans and crip embodiment in ritualistic relationship to time. The body of work includes window-like assemblages with foraged materials collaged on stretched and deconstructed plain white t-shirts, many hung inverted. Ghostly in their flattened corporeality, Tepper’s torso-shaped make-shift archives testify to fragility and chronic pain, navigate risk and protection, and hold on while on hold. Within their depths: detail-rich portals, which hold and suture together fragile and precarious ephemera, including personal medical records and waste, construction materials, and detritus in pouches and holes resembling a double-sided game of Operation.

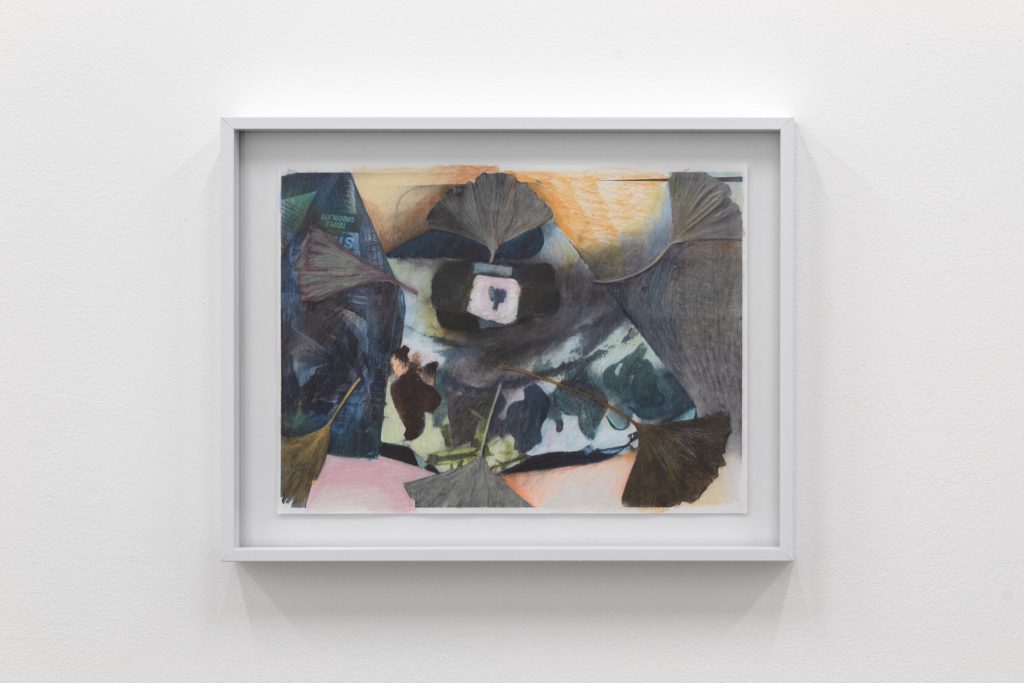

Tepper’s human-sized art invites the viewer to keep company with and stay present for the shapeshifting animacies in all manner of unexpected natural and synthetic materials; the brimming inventories of Tepper’s material lists feels like skimming poetry: alcohol swabs with pareidolic angel blood stains, volcanic rock, ginkgo leaves, “kid’s jacket remnant with metal zipper,” suppository inserters, Ricola cough drop wrappers (calling to mind Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s diminishing candy piles), “upholstery foam ripped up by dog,” cicada shell, fishing line, seeds, and dirty envelops, among other miscellany.

Walking up to the opening and peering through the windows, my friend ABC excitedly exclaimed that the exhibit looked like something else. The expression was idiomatic, he quickly clarified—but the phrase stuck with me as I sat with the self-contained semiotic interplay in this shapeshifting and highly specific body of work, which adaptively works in whatever’s found on hand into an interrelated ecosystem. Something else: what was the y to the x, where would the metaphor go, what reference carried in mind? From Tepper’s exhibit text: “This world has required us to be hard, and yet—deep time reveals that rocks are extremely squishy.” The bounds and boundaries of our bodies are slipperier than they first appear.

including tape, silicon caulk, thread, quilting pins, Ziploc bags, run-over cardboard boxes, eroded journal pages, alcohol swabs, seeds, cicada shells, Ricola wrappers, sanding sponge, binder clips, etc. Image courtesy of Prairie, Chicago.

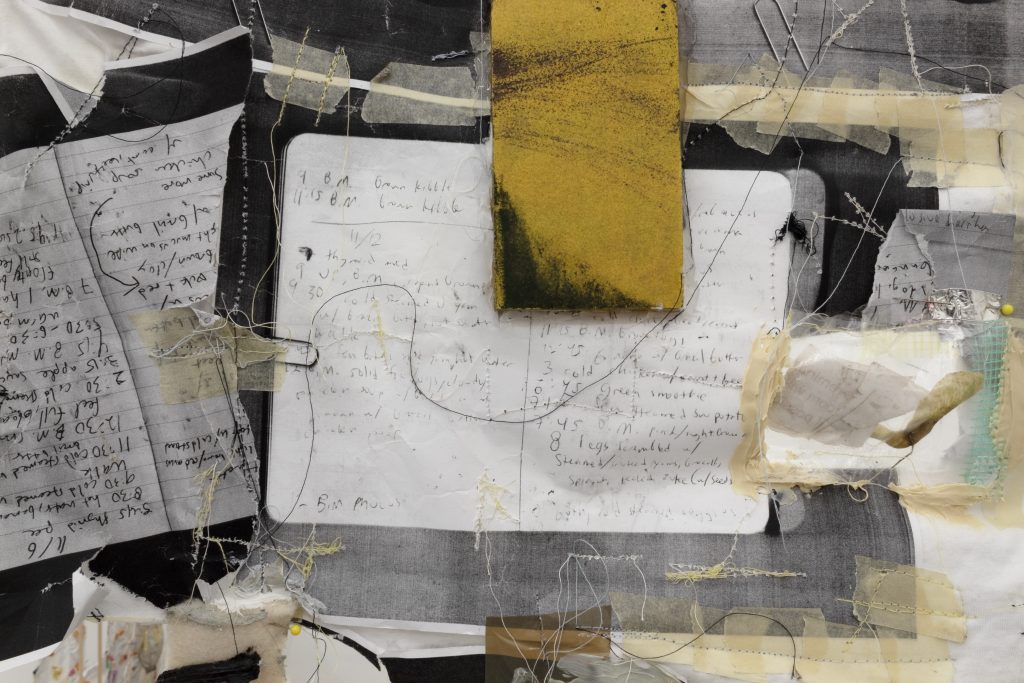

All sorts of methods of flow and disruption, through various techniques and technologies of seams, sutures, adhesion, visual and textual puns. Body humor galore; for instance, the glory-hole-like orifices of silicon rubber plumbing gaskets or the improvised catheter with a crushed water bottle and PVC tube and a delicious dabble of yellow, which my doctor pointed out when we walked through the show together. Eddies of textures blurring nature and man-made medical records: an emphasis on forms of excess, seepage. Things in their ipseity, outside of their use-value, feature as patterns and textures, such as scans of paper clips. These xerox scans, unlike medical scans, gesture towards zines and the bodily autonomy of punk culture, which disavows expertise and privileges subjective and communal experiences. While the shirts in the show function as canvases rather than wearables, there is a clear through line to Tepper’s DIY practice of making and gifting t-shirts for other trans people.

In A Shared Language Shirt (me, dad, and B.), the “shared language” of the title is the synonymous handwriting of Tepper, his father, and his research subject, Beverly Buchanon—another disabled artist from Georgia, who also went to the same local pharmacy. The blurred penmanship creates an uncanny effect of time travel across a palimpsest of xeroxed calendars and journals from various decades, which are collaged and sutured in various orientations, laid on a grid while simultaneously disrupting the linear thrust of the modernist grid (with its ableist logic of the capitalist grind). Instead, the layering emphasizes lineage and relation, porousness as a point of identification. Here is an alchemical grammar for articulating the fluid materiality of time on a bodily level, as it moves between and beyond specific people and places.

A meditative patience is encouraged and rewarded in deep diving into the obsessive and unbounded qualities of Tepper’s art. In slowing down, there is an ecstatic form of witness that verges on collaboration, meeting the sacred interdependence of things and bodies as precious and precarious. The less bounded dribble of drug time and chronic pain out of the catheter into the deep time of a geological record—what else to call this experience but an encounter with the sublime?

About the author: Noa Micaela Fields is a trans poet with hearing aids. She is the author of the poetry book E, forthcoming from Nightboat Books. She lives in Chicago, where she frequently organizes poetry readings, makes zines, and goes out dancing. www.noamicaelafields.com