In Greek mythology, Andromeda was a princess like many before her, achingly beautiful, conspicuously silent, and waiting to be rescued. In her young life, her beauty had been her foil; her mother, Queen Cassiopeia, boasted that her daughter was more beautiful than the Nereids, the daughters of Poseidon. When the Queen’s blasphemous words got back to the beautiful sea nymphs the enraged Nereids demanded justice from their father, the god of the sea. Justice came swiftly in the form of a wild sea beast that ravaged the coastline of the princess’ kingdom. The ruler of that kingdom, King Cepheus, concluded that the only way to appease the angry sea god would be to sacrifice his precious daughter to the monster. And so poor, beautiful Andromeda was chained naked and shivering to a rock in the ocean to meet her fate. When the hero Perseus flew over in his winged sandals, he first saw her on the rock and mistook her for a marble statue. Entranced by her beauty, the hero and demigod swooped down, murdered the beast, rescued the princess, and made her his bride. Artist’s depictions of the mythological Andromeda are often of an unclothed, fair beauty with flowing hair, cowering on the edge of a rock. But, her parents King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia reigned over Aethiopia, which in ancient times meant “burnt faces.” The term became a stand-in name for faraway lands and is the origin for the name of the modern African country Ethiopia. Therefore, Andromeda, a woman who was so beautiful that she offended a god and captivated a hero, was most likely Black, or at the very least, was brown.

The whitewashing of Andromeda illustrates the tension between white supremacist beauty standards and art. The key to understanding this tension lies in Andromeda’s nudity. Her beautiful, vulnerable nakedness is how she appears at the climax of the story, and it’s what made Perseus fall instantly in love. Humans have always been fascinated with their own nude form. Our ancient ancestors carved naked figures into rock walls and crafted fertility totems of lush blossoming pregnancies. In fine art, the nude figure appears frequently, the nakedness often used as an exploration of beauty, or a celebration of strength. It is typically seen as a classic, respected, traditional subject matter in the canon of art history. But the nude bodies seen most often in museums as paintings and sculptures only pay tribute to a specific kind of beauty. An online search of famous nude art brings list after list containing art history’s greatest hits. There’s The Sleeping Venus by Titian from the 16th century, which is believed to be the first western painting of a reclining nude. And there’s Édouard Manet’s nude Olympia, who in the 19th century ushered in modern art by gazing back at the viewer non-allegorically. And Pablo Piccasso’s deconstructed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, whose abstracted bodies appear in the 20th century and mark Picacasso’s foray into cubism. Across subject matter and genre, the most celebrated and canonized nude figures in the canon of art are white women.

Western art’s exaltation of white femininity has made the nude figure in fine art almost completely synonymous with whiteness. One notable exception is Portrait of a Negress or recently retitled Portrait of a Black Woman, a painting by Marie-Guillemine Benoist. The painting portrays a seated young woman with deep brown skin. She’s robed in a white garment that is draped below her shoulder and gathered at her waist, exposing her bare chest. Her hair is covered by a white turban and a single hoop earring dangles from her right ear. The painting debuted alongside other contemporary portraits at the Lourve in 1800 and the response was immediately negative. One critic famously disparaged it as “noirceur” or “black stain”. On the other occasions when brown women appear naked in western art history, they’re likely to be shown as slaves or oddities. The cruel depictions of Saartjie Baartman, a Black South African woman more commonly known as the Hottentot Venus who came to prominence in 19th century Europe as a sideshow attraction, show the legacy of the brown nude as an ethnic caricature, hypersexualized to the point of pornographic, and wholly different from the soft classical portrayal of white nude figures. With the artistic emphasis on their differences rather than their humanity, the brown nude has been denied any opportunity to be seen as delicate or sensual and historically only been allowed to exist as an unequal other to its white counterpart. For more evidence look no further than the term ‘nude’ and how it became explicitly divorced from brown. Crayons, make-up, bandaids, pantyhose, each item borrowed the term nude and used it to mean white, peach, caucasian. In other words, not brown. The concept that nude beauty equals whiteness is so culturally ingrained that as far back as the 14th century, in order for artists to make sense of the story of the beautiful nude Andromeda, she would have to be white despite being from a kingdom in Africa.

They say that the past is prologue. If the nude in art is meant to celebrate the human form and historically it has done so by completely ignoring non-white figures, what becomes of the brown nude in contemporary art today? Because of its detractors, the brown nude in art has never been able to exist as it is: an exploration of the beauty of brown women. Contemporary artists who portray nude brown women with love and dignity are pushing back against a society that decided that brown women, unclothed or otherwise, could not be beautiful. Not only are these artists adding to the narrative, but they are doing it in a way that gives autonomy to the subject. These are not the nudes of the past; they’re complex, bold, and in control. These undeniable works are commanding space in a centuries-long discourse that has until recently excluded them both as subject matter and as artists.

New York-based artist Bianca Nemelc rejects society and all of its negative characterizations of brown women and places her gorgeous brown nudes in a solitary, tropical paradise. The faceless brown women in Bianca’s images are alone and unbothered. Their identities stripped away, her figures are removed from society and devoid of its pressure. In their private moments of paradise, the subjects are indifferent to the viewer. Nemelc reduces the bodies of her subjects to curvaceous shapes, rounded bellies, and buttocks, two ovals become breasts with perfect twin circles as areolas and smaller darker brown circles as nipples. Each abstracted woman is comfortable in their brown skin and happy in their abundance. Their brownness complemented by the bright colors of their surroundings. Reds, oranges, and yellows serve as backdrops to the buoyant abstract figures. The history of Black women’s body sovereignty has been a fraught one. But on Nemelc’s canvases, that’s all gone, and each woman is afforded a private moment of complete comfort.

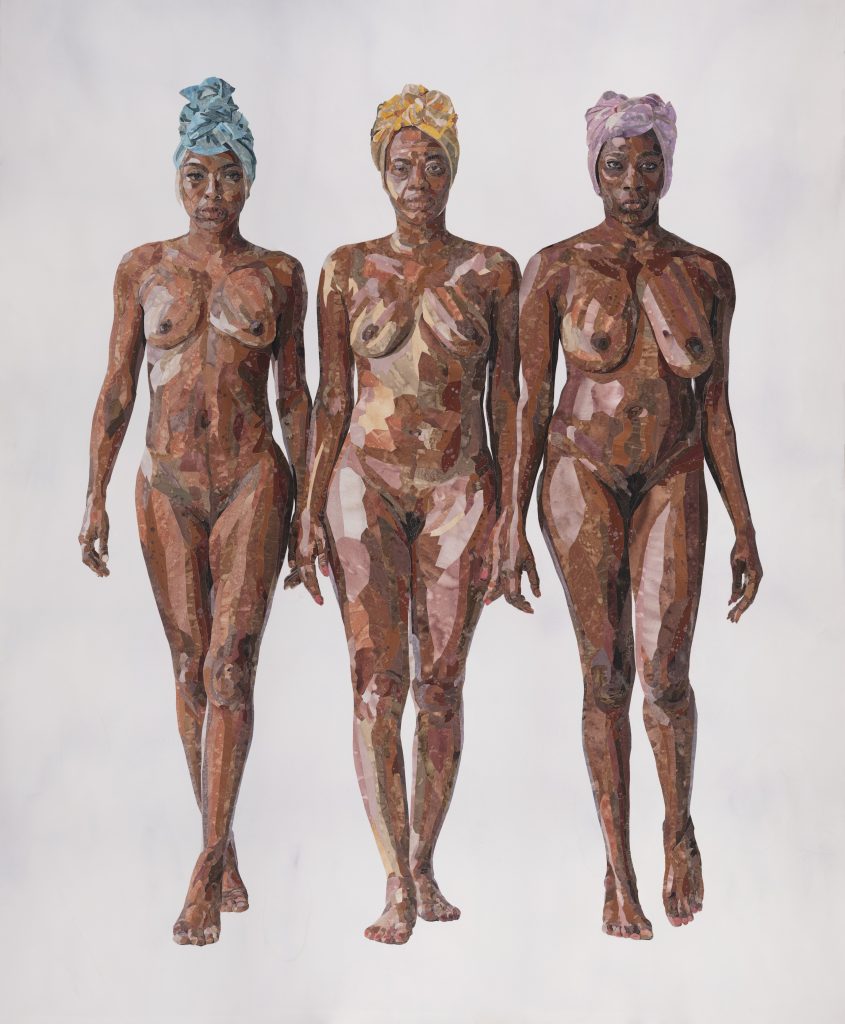

Capturing the tones and hues in brown skin can be challenging. Shades of brown can be made by combining red, yellow, and black pigments, or by combining orange and black. Los Angeles-based portrait artist YoYo Lander mimics the color mixing process through collage to create the brown skin of her subjects. Her technique of layering strips of dyed watercolor paper celebrates the variety of colors present in brown skin. Lander’s subjects are more than brown, they’re the spectrum of color. In their skin, they have whites, yellows, pinks, and greens. Like their layered skin, her subjects are portrayed as nuanced and emotional. The Black women in her work contain multitudes as she captures their moments of humanity. The collaging effect makes the figures seem both delicate and strong at the same time. Whether it’s three Black women walking together as a unit of strength, or a single Black woman wrapped in a sheet with her head cradled in her arm, each portrait is more than the sum of its parts. They’re pensive and sleeping, their hair is wrapped in turbans or pulled together in twists. Her painstaking attention to details gives the women full identities. These aren’t anonymous models, they’re women who get their nails done and wrap their hair at night. They’re the Black and brown women in our everyday lives.

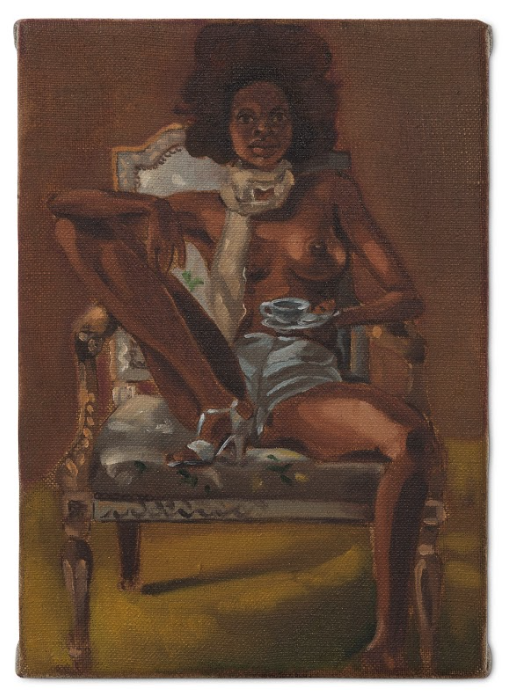

The brown figures on Somaya Critchlow’s small canvases pose an uncomfortable question: who is sexualizing this body? These subjects aren’t like the languid wispy nudes of yore. With their full lips and broad noses, Critchlow’s women are unapologetically brown and neither passive nor subtle. They have buxom bodies with round hips and large breasts with nipples that protrude like chocolate kisses. They are active and self-assured with complete autonomy over their bodies, yet playful and campy with their massive wigs and various costumes. Even when her subjects are clothed, their bodies are on full display. At first blush, Critchlow’s exaggerated figures appear very sexual, especially in a society that has been taught to treat brown women’s bodies as sexual playgrounds. But on the contrary, the women stare back at the viewer, not alluringly, but defiantly, almost with a smirk. They’re in on the joke. Critchlow’s figures do whatever they want, wear whatever they want, they’re over the top but uninterested in anyone’s opinion; a tribute to the self-contained black women.

Black skin and red lips have been hallmarks of racist caricatures of Black people for centuries. South African artist Zandile Tshabalala flips that notion on its head and the effect is arresting. For Tshabalala, the blackness of her subjects is unequivocal. Their skin is a sultry, inky black that contrasts against their bright cherry red lips. Their elongated, voluptuous figures are not only beautiful but confidently sexual. You’ll find them nude luxuriating in bed or among nature gazing at the viewer with lidded, come hither, eyes. But unlike offensive portrayals of the past, these Black women own their sexuality. The women in Tshabalala’s paintings are inviting, but more importantly, they are clearly fine on their own. Tshabalala’s paintings boldly refute the perceptions of Black women as undesirable yet hypersexual and take back the sexual agency that has long been denied to women of color.

Representation matters and Black figurative painters are on the rise. In the wake of the 2020 protests against racial injustice, the art industry rushed to bring more Black portrait artists (who in turn create work portraying the Black figure) into the mainstream. At a time when it was desperately needed, Grace Lynne Haynes, Kerry James Marshall, Jordan Casteel, Amy Sherald, all had their paintings of Black women grace magazine covers in 2020. Each cover was a unique tribute to Black femininity, and as more instances of Black women as dignified subject matter reach the mainstream, a unique opportunity is created for Black women to wrest back their narrative. The lovingly crafted images of nude Black women created by Somaya Critchlow, YoYo Lander, Bianca Nemelc, and Zandile Tshabalala all exist in contrast to the racist and harmful stereotypes that proliferate through our culture. However, after centuries of damaging imagery, it will take time and effort to course-correct that narrative. Until then, the brown nude will always live at the intersection of the politics of beauty, the politics of race, and the politics of femininity–never fully existing in any.

Featured image: Deep Water and Drowning Are Not The Same Thing by YoYo Lander, 2019. The mixed-media piece shows a nude woman with brown skin sitting with her head in her arms. She wears a red head wrap and sits on blue sheets. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is a arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago IL.