Featured Image: Cecilia Beaven sits in a gallery in front of three of her large yellow and black paintings, which are included in the show “Dream” at Hyde Park Art Center. Cecilia sits in a chair, looking off to the side. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Para leer esto en español, haga clic aquí.

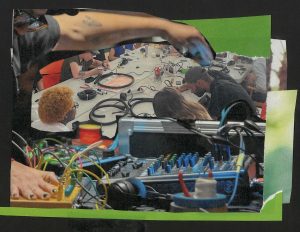

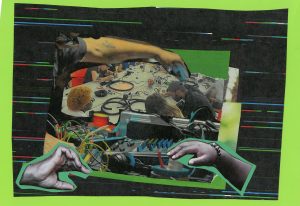

When I walked into Cecilia Beaven’s Hyde Park Art Center studio last fall, I was struck with an immediate feeling of déjà vu. Curious and hoping to understand why, I moved slowly through the space, looking around at her comics, illustrations, weavings, and the animation looping on a small screen in the center of the room. When my eyes came to her paintings and small ceramic sculptures, I remembered immediately: in the earliest weeks of 2020, I saw Cecilia’s work at Plomo Gallery in Mexico City and, not only had I seen her work, but I’d spent hours sitting with it and falling far into the allegorical containers she had created. I was pulled by her ability to make work that offered mystery, wonder, humor, and vulnerability through breadcrumbs that have been loosened from autobiographical and ancestral stories.

As you can imagine, our studio visit covered a lot of ground. We discussed international comic artists, Nickelodeon cartoons, and our experiences as the youngest of the siblings in our families. We talked about how even though her practice moves across mediums fluidly, that doesn’t stop her from running into occasional learning curves. We shared our thoughts on the weight and limitations of labels and how we shake them off or shape them. We went even further, talking about the ways that labels change in different geographies and social contexts, and how disorienting race can be for those who immigrate to the United States. After re-reading this interview, I remembered the strength of the draw that her work had on me when I first saw it two years ago. Then, I thought about how impressed and inspired my pre-teen Saturday morning cartoons-loving self would be after seeing work like this and hearing Cecilia’s story.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tempestt Hazel: I’d like to start with an introduction. How would you describe yourself as an artist?

Cecilia Beaven: As an artist, I define myself as a maximalist and a playful artist. I’m Mexican, and that comes into my art as well. I love storytelling, mythology, and fables. I was trained as a painter, but I do multidisciplinary work. I have a desire to create and do images in different mediums and materialities.

TH: To step outside of your practice for one second. We’re transitioning into a new year and you’re also coming to the end of this residency at Hyde Park Art Center. What’s at top of mind for you right now since this tends to be a time of reflection?

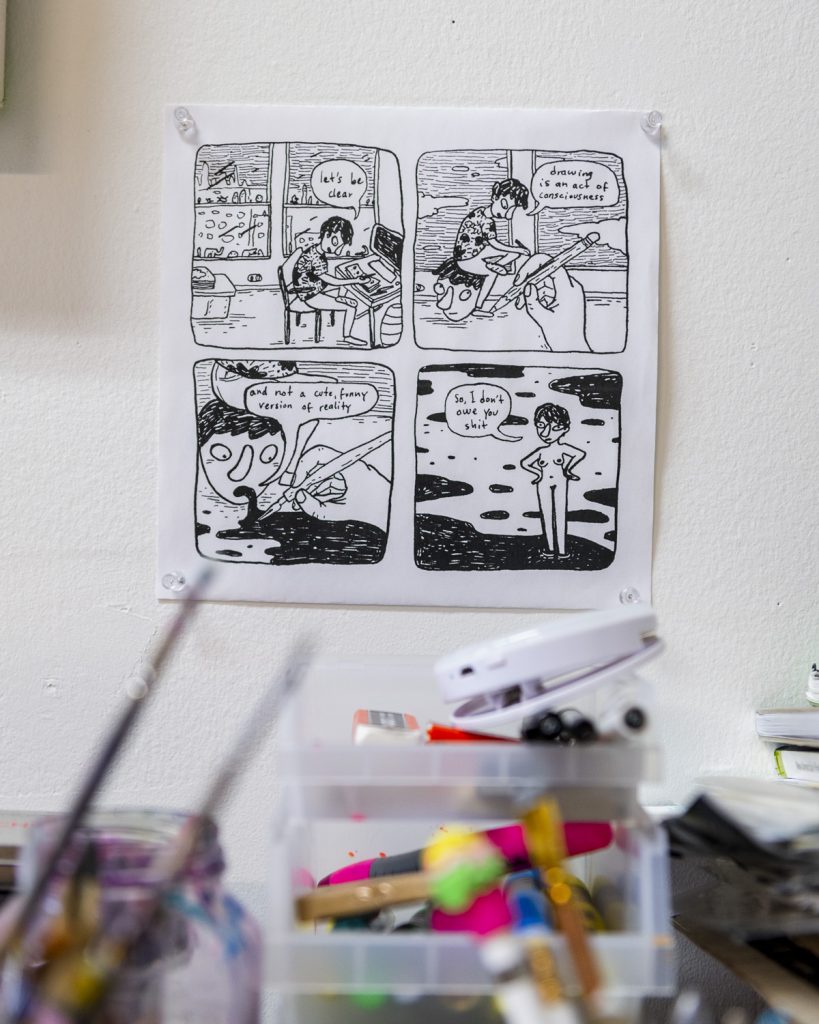

CB: My first feeling is of gratefulness for the space. I truly loved it and it exceeded my expectations. It was amazing. And getting to know everyone at the Art Center — very nice and good-hearted people. When I think about personal goals, it’s funny because I started with a very defined idea of what I would do this year. I can get distracted and jump from one thing to another, so I was worried that would happen. But I surprised myself by doing work that I didn’t anticipate and didn’t end up doing the work I thought I’d do at the beginning of the year. That’s funny. I thought I’d do a lot of comics — which I think I told to you last time you were here. I didn’t get there and I think that was a lesson to learn this year: making comics is super time-consuming and I need to be more committed to that project without having other projects on the side. So, hopefully in the new year!

But I’ve been translating the language of the comics into other forms, which is something I didn’t anticipate. The paintings I’m working on, which will be part of [Hyde Park Art Center’s Dream] show downstairs, sparked from what I was thinking of in the comics. So, the comics turned into something else. The mosaics also follow that logic. I was thinking about what it would mean to make a physical comic where the animals were tiles. I was surprised by how the projects changed.

I was able to make use of the space. I was really happy and the view made me happy [laughs]. It was a good experience overall.

TH: Do you have any rituals you do around this time of year?

CB: Yea! Something that we used to do in our family, in Mexico, is we would write our wishes for the next year on a piece of paper. You can write twelve.

TH: That’s a lot! I don’t know if I could think up twelve wishes.

CB: It’s actually not a lot! When you start writing you realize that you need more. So, when you’re a kid, you do wishes, but [when you get older] you think of them as goals — you have to be the one to make them come true. Then, you have to fold the paper twelve times and hide it somewhere. It’s something that I still do on the last day of the year. I think it’s just a good moment to reflect and get new objectives for the new year.

I also try to plan out what I want throughout the year, but on loose terms. I also don’t want to be too demanding of myself and set expectations that I cannot fulfill.

TH: You spoke about family, and when I look at your work I see so many different things. One of the things I appreciate is how you insert yourself into your work. It’s subtle but also clear. I’m curious about if your family shows up in a similarly subtle way.

CB: Not really. Recently, through the comics, I’ve been including them a little more. But the comics are more autobiographical. My family appears because they’re part of my life, but they don’t play the same role that I do in my artwork. [Their presence] is more literal.

One of the projects that I started this year that was really hard to continue because it took a lot of time and emotional energy, was a comic about growing up in Mexico. It focuses on my dad and his weird relationship with my mom. So, I started to draw my dad repeatedly, which is something I’ve never done before. When I was in art school in Mexico for my BFA, I did a series of portraits of him, but, since then, I don’t think I’ve drawn him. So, [drawing him now] was new and fun — I started to see him as a character in my world. I was thinking about his different profiles, angles: how he looks walking or sitting down, how he looks when he’s crying. It’s a nice way to understand a person and try to think from their persona.

TH: As you were describing that, I started to think about how there’s a difference between feeling like you know the people in your life and their mannerisms, but then how that might change when you study them. Through that process, was there something that revealed itself to you about him that was unexpected?

CB: It was definitely emotional. When I drew him crying — and I’ve only seen him cry once in my life — drawing him in that moment made me cry. I don’t know if anything revealed itself though.

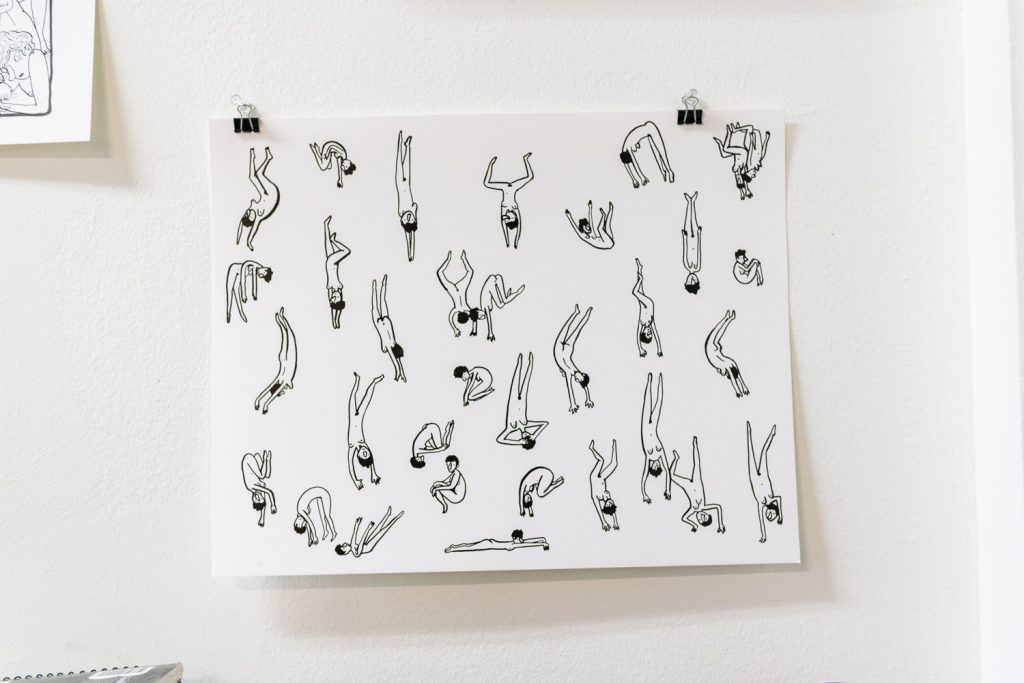

TH: When inserting yourself into your work, what’s the motivation?

CB: I’ve been doing this for a long time — trying to see myself as a character who can belong to the worlds that I draw, paint, or sculpt. It started as a game, to be playful and draw myself as a funny character — something different than a self-portrait. I also love cartoons and graphic novels. So thinking of my drawings as characters felt good and felt right. I started to reflect on what it meant to look at myself from outside. Whenever I drew myself, it meant that, metaphorically, I had some distance from myself. It allowed me to be more introspective, and even to be more mindful of how I look and how I look with different emotions. I can be more mindful of how my body feels and how that affects how I look. It can be realistic and unrealistic. Like the tiles, some of the poses are unrealistic but they reflect how things feel inside of me. Then, I really got interested in how insightful I could be and reflective of myself and my life — the happiness and absurdity of just being alive. How joyful, weird, and nonsensical it can be.

TH: That’s real. You’re inspired by graphic novels and it’s impossible not to see that in your work. What are some of your favorites?

CB: I have so many! I love Chris Ware who is from Chicago. The first two graphic novels I got fascinated by in college was Epileptic by David Beauchard, who is a French author. Then Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware I think those two made a really big impression on me — I’d never seen that format of graphic novel. I’d seen comics and even independent comics weren’t really a thing in Mexico. I’d seen commercial comics, and I liked them, but I didn’t feel a strong passion for them. But those [graphic novels] blew my mind.

Some other authors I love right now are Power Paola, a [Colombian-Ecuadorian] author and a strong figure in Latin America. I love Jim Woodring from the U.S., and Emill Ferris, (her work is more recent but she’s an SAIC alumni.) Michael DeForge, he’s a Canadian author and I really love his work. He has such unique figuration and stories.

TH: I’m curious about your relationship to telling stories and where it all began. I realize that there’s probably a difference between when you first remember it coming into your life and when it became a part of your practice, but what made you learn to love storytelling?

CB: Well, the love for stories started with cartoons when I was a kid. And movies. When I was a kid, my mother ran a video rental store, and this was before Blockbuster came to Mexico. It was a Mexican company and went out of business when Blockbuster came. She ran this business and that meant I had access to hundreds of movies. I’m the youngest of three sisters, by far. The oldest is fourteen years older, and the other is six years older. I think my parents were tired of raising kids [when I was born].

TH: I’m the youngest of six, so I know that feeling!

CB: So all the rules that applied to my sisters didn’t exist for me. I could watch any movie I wanted — horror or anything!

TH: You’re speaking my experience!

CB: Yes, I watched so many things. And I loved it. I loved how you can tell stories with images. Then, I watched cartoons compulsively, Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network, all of it. I also knew stories through my family. My grandma would sing children’s songs that were stories and my mom would read to me at night sometimes. I was surrounded by fiction. It was a nice way of existing in the world.

I incorporated it into my work once I started drawing myself a little after college.

TH: Then there’s the mythology you incorporate in your work. You’re not necessarily trying to tell specific stories of mythology that are widely told or widely known, but you’re incorporating elements of those stories in your work. Can you talk more about that?

CB: I love mythology as part of storytelling. I love it in general and am interested in learning about myths from different places, times, and cultures. Even when I’m traveling, that’s something I like to research about where I am — what were the first stories told about that place? Following that logic, in Mexico City, where I’m from, the original stories and first stories were told by the Aztec people before the Spaniards came. Even though there’s a lot of pride in Mexico, at least recently, to show indigenous roots, these stories [still] aren’t that well known. Which is sad. The mythology that we all have has more to do with Catholic myths than all the stories we were told way before then. So, I’ve enjoyed reading about that mythology and knowing more about it — the visual codes they used for the writing. That’s something that I take as inspiration into my work. But, like you said, it’s not to tell a specific story but to reflect on this time and this place. Also what it means to think about mythology that’s so old. And it forces me to think about the mythologies we have right now that we don’t even see because we just exist in the world. [We also] think it is what it is, but we forget that we made the rules and it’s a game we’re playing. There’s a game board.

Mythologies are a way of understanding the world and explaining the world to yourself. Right now we have many different ways of understanding the world and explaining it to ourselves, and that’s what our mythology is. If someone were to look at it a thousand years from now, it would look like a naive mythology — which is the same thing that happens to us when we look at old mythologies and they look like folktales or naive mythology. But we are humans, we keep changing, and we try to explain the world somehow. And we sometimes have to put some fiction into that. So, that reminds me that this is still a game. We’re playing roles that we set on ourselves — and that allows me to look outward.

TH: On the point of us making the rules… I was listening to one conversation that you did for Lit & Luz Festival, and I was drawn to something you said about how you do and don’t identify — the decisions you make around the labels that are placed on you. It made me think about how, for me, there are labels that I know are inherent and are just on me because I am who I am. But, at the same time, how I choose to talk about myself from one moment to the next can change and I can decide to drop those labels, because as you said, we make the rules — we have that capability to a certain extent, at least. On the Lit & Luz panel, you were talking about that.

I wonder what you think about us all having the power to define ourselves and decide what we want to do with the labels — ones placed on us and ones we inherited. Right now, exercising that power can be challenging against the backdrop of today’s social climates. It’s hard to hold onto more nuanced ways of identifying ourselves when the arts and the world often want to be able to pull out and highlight the most useful pieces to them — or, we, ourselves, strategically pull them out when we want or need to.

You make work that explores openness and freedom. All that said, my question is how do you maintain that openness and freedom within your work under today’s context and the times we’re living in?

CB: That’s a great question. It’s challenging. On one hand, I know that these categories apply to me and define me in several ways. But also, the negative part is that my culture can get reduced — my personality too. So, I try to play in between those places. I show affiliation with my cultural identity, my presence here as an immigrant, or whatever. I try to take that, be honest about it, and think about it — but also try hard not to fall into the cliches that are expected of me, especially in the United States.

For me, that’s a new way of thinking about myself, since I came to Chicago in 2017. Before that, I was a Mexican in Mexico, so I wasn’t thinking about being Mexican, it was just my reality. Mexico is way less diverse than the U.S. Coming here, seeing how diverse it was, but also divided: that was new and surprising for me. I had so many key moments that revealed that I was in a new reality. People started asking me if I felt out of place. It made me say, “Whoa, now that you say that…I guess I do.” [laughs]

TH: It’s like, “Wait…do I? Hm, actually yes, yes I do…”

CB: Someone asked me where I lived, and I said Gold Coast. I didn’t even know what it was, I just found a place that was affordable and close to school. And then, later, I realized what Gold Coast was. And a girl asked me, “Why do you live there? Why don’t you live in Pilsen, that’s where the Mexicans are…” There were so many key moments. All of a sudden I was a “person of color.” I’d never thought about that term before. We didn’t use it in Mexico. Of course, we distinguish color, but we don’t use that term.

So, I was like, “wow, I’m a person of color.” I started learning about all of these categories and expectations. I want to play with them and be controversial with them.

TH: Has it become a new factor that you’ve had to wrestle with in your practice and your work?

CB: Absolutely. When I was in Mexico, I didn’t have all of this in mind. I wasn’t really thinking about how people would read my work because I assumed we were sharing a cultural background and understanding. But when I came here [for school], it became clear that I didn’t share a cultural background with hardly anybody. And if I did something that looked “too Mexican,” it would disappoint some people or attract some people for the wrong reasons. I think I changed my style when I came here. Maybe a little bit.

TH: How would you describe that change?

CB: Well, like these paintings […] are an example of that. I was trying to incorporate mythology and think about the myths that come from the Aztec culture, but also creating some ambiguity around them so that they don’t look like they come from an immediate or specific place. They still keep elements that talk about Mexico, but in other ways than the imagery — like the colors or the masks. These are decisions I made while living here. I wanted to leave things a little more open so that everybody can feel welcomed and invited to look with curiosity. They can add their own ideas, narratives, and interpretations. I want people to feel included, welcomed, and curious. If my work can do that, then I’m happy with that change. Maybe some of the work I was doing in Mexico was constricted in that sense, and it would be harder to see [these things] outside of Mexico.

TH: I don’t want to make a total generalization, but I think the majority of people in the world have encountered things like comics and cartoons. And your use of color draws me in. That, combined with the figures and characters you create, opens things up for interpretation in incredible ways. But there’s something grown about your work…

CB: …like a dark aspect? Yes, I love playing with the contradiction between the playfulness and darker places. It’s introspective and psychological.

TH: Also, the feminine energy in it seems important. I can see how that could maybe just be because of that connection to you as a person — and many of the characters in your work are you. Other than the parts embedded in the work that are a reflection of yourself, are there other feminine energies harnessed in your work?

CB: Mexico is very misogynistic, very machista. The main mythologies — both Aztec and Catholic — are misogynistic. I think it’s interesting to flip that and think about other ways that things can be. In my family, the women figures were very important. But my dad too. I have two sisters, and we, with my mom, would spend time with my great aunt and aunt. I grew up surrounded by women. Those were the people I truly admired and wanted to follow. There’s a lot to say about that. There are also so many women doing work that’s trying to compensate for the imbalance of art history. I’m just trying to do my part on the team.

TH: I love how you don’t limit yourself with the mediums you explore. What I find so beautiful is that you take the stories that you’re telling about these characters who are consistent and recurring, and you translate them into other formats. What moves and motivates you to explore a different medium?

CB: First is curiosity: just to try out a new material and see what possibilities it offers visually, aesthetically, conceptually, or metaphorically. I love using my hands and different materialities give me different experiences. I can’t decide on one. And I love combining things whenever I can, especially when I install work. I love having a sculpture combined with paintings, or a projection over a painting. I like playing with formats and multimedia things.

I could be doing a little drawing, and I could start thinking that this particular drawing could be a great ceramic sculpture. I can see its format, size, and glazes. Then, the glazes could get me thinking about painting. I jump whenever it feels right. I like seeing the parts as one organism. The short answer is that it’s just me being playful and maximalist.

TH: I’m going to try and name them all. You started with drawing, which is related to the comics, then there’s the paintings, then ceramics, and murals, and the animations — which are also related to the drawings. Which of these had the steepest learning curve for you?

CB: I guess the animation. It’s time-consuming, which is why it’s so powerful to look at animation because you can really tell the effort and the hours that went into just a few seconds of animation. You almost feel guilty blinking when you’re watching it because you know you’re missing someone’s hours of work. I don’t understand how people ever look away! You’ve got to pay attention. [laughs]

Drawing is the easiest. It’s what I started doing when I was a kid. It’s my happy place and comfort zone. Murals are challenging — not exactly hard, but physically challenging. You’re using your body in different ways, climbing ladders and scaffolding. You have to be adventurous.

TH: When I see your murals, I think about the difference between how these characters show up in the space of your studio, a website, or gallery space, or classroom. But do you think about your work differently when it’s out in the world, in outdoor public space and out in the wild?

CB: …where it’s more accessible. Yea, I love it. My family isn’t a family of artists and I didn’t grow up in particularly artistic environments, even though my family is really supportive. So accessibility is something that I care about a lot. I like the clean walls of galleries, but I don’t like the snobbish aura of galleries and how so many people don’t go because they don’t feel welcomed. So, murals and comics share a more democratic approach to the public, which I love. Muralism is also a big tradition in Mexico that I grew up seeing and admiring.

TH: When it comes to the comics and the graphic novel — which sounds like it’s a kind of autobiography — what is your writing process?

CB: I try to do both things at the same time through my sketchbooks. I write a little, draw a little, sometimes write a lot. But I keep them together, I try to keep text as part of my visual diaries. Then, when I want to tell a story I think about an idea, loosely write what it is, make some drawings, then I continue to make the writing better and more precise. Then, I begin to plan how many panels are needed to tell these stories and what size they need to be and where the text and drawings go. When I put everything together I then have to put it in a cohesive format. It’s tough to tell stories that make sense. I love the challenge, but it’s not my most natural talent.

TH: I’m really excited to see the final piece. Your comics and animations remind me of some of my favorite filmmakers who make stories at the edges of reality — strange and stretched nonfictions. Your work attempts to break those walls. There are a lot of children in my life and your work reminds me of my time with them. It’s not that your work is childlike, but rather it’s more honest about and more fully reflective of how the world actually is. It’s exciting to think about the playfulness and blending of fiction and nonfiction in your work — it’s the type of space we need much more of.

CB: That’s good to hear because it’s hard and takes time. It’s good to know that other people are interested and think it’s a necessary project. It’s necessary in order to keep going.

TH: Continuing with the aspirational piece and with no guilt towards what wasn’t accomplished in 2021, what do you see for yourself in this new year? What do you hope for?

CB: I hope to focus on the graphic novel project. I have a very good start but I want to guarantee some time to work on it. It’s something that I need to do and that will be healing for myself and other women who have experienced similar machista environments.

I also want to keep coming to ceramic workshops here [at Hyde Park Art Center]. Also teaching, I hope to keep doing that forever. And, of course, finding other residencies.

TH: I’m curious about your teaching and what it’s like teaching right now. Without pushing past any thresholds of trust for your students, what has the experience in the classroom been for you during this time? That can be when it comes to what the students are making or the conversations happening in the space.

CB: It’s been great to be in a space to share and hear fresh ideas. As teachers, we’re there trying to guide them but also to learn from them. You have to be careful that you’re guiding them and not erasing their innovation. I love seeing how they grow and understand things, then incorporate it into their work. I love seeing how things get refined. In art school, people grow so much — it’s amazing to see from the outside.

I also think about myself when I was that age and at that time in my life. I remember how it feels and how exciting it was. It’s so cute to see them in that moment, realizing things about themselves and them in their professional world.

TH: Is there anything you bring into your teaching practice that was informed by how you were taught?

CB: Yes, but also some things that are informed by what I wish I had been taught and wasn’t. I try to make my class focused on different expressions, countries, cultures — as little focused on Western art history as possible. I try to give as broad of a scope as I can. Sometimes that means doing a lot of research and not taking for granted what I learned and what I was taught was important. The work is worth it. I also teach what I found valuable in my own education.

TH: I hear that. A lot of the reason Sixty was started was because of the art that we weren’t learning about or seeing in our education. So, what’s on your studio playlist?

CB: I was just talking about this with a friend. Listen — we were sharing our playlist highlights. It turns out I listen to The Avalanches the most.

TH: Really!? I love The Avalanches! And they have great music videos. I think I still have one of their physical CDs from a long, long time ago.

CB: It’s interesting, innovative, and weird. I like playful music. Animal Collective, some things in Spanish that my parents used to listen to. It depends on my mood.

TH: And my last question is an archive-related one. You have so much work in different forms. Two million years from now, if this planet is around, and people are digging and find work of yours, what do you hope they would find?

CB: Probably one of the ceramic sculptures because those might be really misleading. Maybe they would think, “Oh, this is an ancient culture of people wearing the skins of animals.” They would come up with different interpretations and probably wouldn’t think that it’s just an artist being playful.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Matt Austin.