Lawndale Pop Up Spot was one of the first projects that came to mind for Steven D. Booth when he and the other members of The Blackivists were thinking through who they would invite to be part of the project Diamond in the Back. Named after the song “Be Thankful for What You Got” by William DeVaughn, Diamond in the Back (DiTB) was dreamed up by Steven and fellow archivists Tracy Drake, Raquel Flores-Clemons, Erin Glasco, Skyla Hearn, and Stacie Williams as a way to deepen and expand their ongoing work to preserve the heritage, culture, and memories of Black people, especially those that intertwine with their own individual stories. Although Chicago has a deep history of documenting Black life through the work of scholars, curators, museums, libraries, historic publications, and other institutions, with DiTB, The Blackivists are focusing their attention on community-held knowledge and preservation styles while considering the expressed priorities of the people living these histories. With this project, they are offering a more elastic and non-extractive approach to preservation and its definitions.

That said, it’s clear why Lawndale Pop Up Spot would be part of the first cohort of projects for DiTB. Since its founding, Jonathan Kelley and Chelsea Ridley have been collaborating with neighbors and artists like Jay Simon to build a street-level community-run museum that seeks to shift what we understand museums to be and what they can potentially be to a neighborhood like North Lawndale. What does it look like when residents of all backgrounds, ages, and interests come together to celebrate the neighborhood’s history and put into words and images their hopes for its future? And what does archiving these efforts look like? Asking questions of how things are and how they could be is an inclination they all share.

The following conversation begins to address these questions, but, in all honesty, what you’re about to read is a love note to Chicago’s West Side, signed by Jay Simon, Jonathan Kelley, and Steven D. Booth.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

* * * *

Tempestt Hazel: Before we dive into talking specifically about this collaboration, I want to root the conversation in your own individual histories. Can each of you give a brief introduction of yourself? How would you introduce yourself to somebody who doesn’t already know you or doesn’t know the origins of your relationship to cultural preservation?

Jonathan Kelley: I’m originally from Denver. My family’s from the Midwest on both sides. My parents met in college, in the 60’s, in Iowa but I grew up farther West. I moved to Chicago, did some community organizing back in Colorado, and for a long time actually worked in the library field, which is where I met Steven [D. Booth]. A completely different life. I was very surprised to be meeting him…happily surprised. In the mid-2010s, I decided to change careers and go to graduate school [to study] museums. [It’s] a change in career, but there are definitely connections between librarian and museum worlds. I went to UIC and I met Chelsea Ridley, who would become the other co-founder of Lawndale Pop Up Spot. It was never clear what that collaboration would look like. But, from the beginning, we knew that we shared a lot of the same interests in terms of how museums could work on a smaller scale in service of community rather than solely being places of collection and exhibition, but really engaged more deeply in the process of community engagement and sustainable community-led building. Long story short, we opened the Lawndale Pop Up Spot in summer 2019. That year we met Jay Simon and decided that it would be really exciting to collaborate with him. So, we did that in 2020 and the project became Lawndale Living History.

TH: I don’t know who to pass it to next because Jonathan, your introduction brings in both Steven and Jay.

Steven D. Booth: I’ll chime in. I was born and raised in Chicago, on the West Side in Humboldt Park. I’d like to think that I’m probably one of very few Black Chicagoans who had a really varied Chicago experience in the sense that my family is pretty much from the North Side, Lincoln Park. But I went to school, high school, on the Southwest Side, and then my family church is in Bronzeville. So, I’d like to think that I’ve touched all areas of Chicago before I left to go to college in Atlanta. My background is in music and it’s through music that I…well, that archives found me. Let’s put it like that because I didn’t find [archives]. After undergrad, I went to Simmons College in Boston to get my Master’s in Library Science. Then, while working in DC for the National Archives, I met Jonathan through a scholarship that I applied for. This was at a point in my life that I would apply for any and everything. I would go on free trips and to conferences. It was a great experience connecting with Jonathan and being a part of that program. I moved back to Chicago five years ago, during a transition, and within the past five years, that’s when The Blackivists was founded, in 2018. It kind of started out as a joke, but quickly turned into something very real because we were finding that, individually, people were asking us for assistance. So, we thought [to ourselves], what would it look like for us to actually bring our experience together and help folks as a collective?

TH: How about you, Jay, how would you introduce yourself and your relationship to cultural preservation?

JS: I’m born and raised on the West Side in North Lawndale and I currently live in South Lawndale. I have the best of both worlds when it comes to Lawndale. My father, he was older, and from Mississippi. He came here when he was sixteen in the 1950’s. He migrated to the West Side and I guess because I had an older father, I was kind of rooted in wanting to know about history. My father was like a historian. He had old books and I would [randomly] grab them, read [a little bit] and it would pique my interest. Now, I am a professional photographer, videographer, and curator. In 2019, I got my first grant to do a photo exhibition, from the School of the Art Institute at Homan Square. My project was based around photographing fathers, it was called Father’s Lead. While a lot of my practice deals with changing the narrative of certain stories, of certain stereotypes, at the time I was a first-time father (my daughter had been born in 2016) and I really wanted to capture stories of fathers who were engaged in their children’s lives. I wanted to showcase that. My goal was to change the narrative of the deadbeat dad stereotype, particularly with Black, African American men. I wanted to showcase the beauty of how Black men really enjoy spending time with their children.

[Later], I did a lot of work with more organizations. One of those organizations was the Martin Luther King, Jr. Exhibit Center, which at the time was the director there was Alexis Young. I was working with her doing small projects and that’s when I met Jonathan Kelley. Jonathan approached me about doing a photo exhibition [at Lawndale Pop Up Spot] with photos that told the story of elders in the community. That really piqued my interest, again, because with me having an older father, I appreciate elderly wisdom. It was already on brand with me photographing fathers, and this would be a different side of the story that could be told. We were fortunate to get StoryCorps to collaborate with us, to capture the audio recordings of the elders and mentors.

The Lawndale Living History exhibit got a lot of attention and continued my desire to archive and tell people’s stories through a different lens. So, that’s where my work is — really grounded in archival [projects] and documenting. It comes from my past, you know, my mom did it. She has the photo books of our family and of my grandmother. My grandmother died when I was two, so that really inspired me to tell stories, to photograph, and document.

TH: I’ll go back to Steven. So, Diamond in the Back is a community archiving project and as part of the project each member of The Blackivists was able to choose who they wanted to work with. You’ve already mentioned your origins and relationship to the West Side, so there’s obviously just some West Side love in this, but I’m curious about why you chose Lawndale Pop Up Spot to be a part of your contribution to Diamond in the Back.

SDB: Yeah, that’s a great question. Of The Blackivists’ members, there are two of us that are from the West Side. When I moved back here in 2017, that’s really around the time that I started learning about Black Chicagoans on the West Side. It was interesting to see that even then, in 2017, that so much focus and attention has been on the Black Chicago experience on the South Side. While there were resources and information [about the West Side], it was very little. I have to credit Block Club Chicago because I think they’ve been doing a really good job of amplifying West Side stories, which is how I learned about Lawndale Pop Up Spot. I thought it would be a great collaboration. I remember reading the about page [on their website], but it never registered that this Jonathan Kelley was the same Jonathan Kelley that I knew from ALA [American Libraries Association]. When The Blackivists started thinking about groups, Lawndale Pop Up Spot was my top choice but I didn’t know necessarily what assistance they needed or if they needed anything at all. But it didn’t hurt to ask. So I cold-call emailed Jonathan, and he replied saying, “Hey, Steven!” [That’s when I realized we already knew one another.] There was already this connection and I didn’t know it. For The Blackivists, we try to partner with organizations that we have a personal connection with, to some degree, because we want to be as invested in the project as possible. With Lawndale Pop Up Spot, I absolutely knew, from the very beginning, that I had to snag it before Raquel did.

TH: On the flip side, Jonathan, I’m curious to hear what it was like on the receiving end of that email and getting a message from Steven.

JK: It was awesome. It was a blast from the past.

We call ourselves a community museum, but we’re certainly not a traditional museum in the sense that we don’t maintain physical collections of objects. We are an exhibition space, and we are very collaborative with the artists and curators that we work with. We also try to do a lot of public events in support of our exhibits and to be in support of the community. So [working with Steven and The Blackivists] felt right, it felt natural.

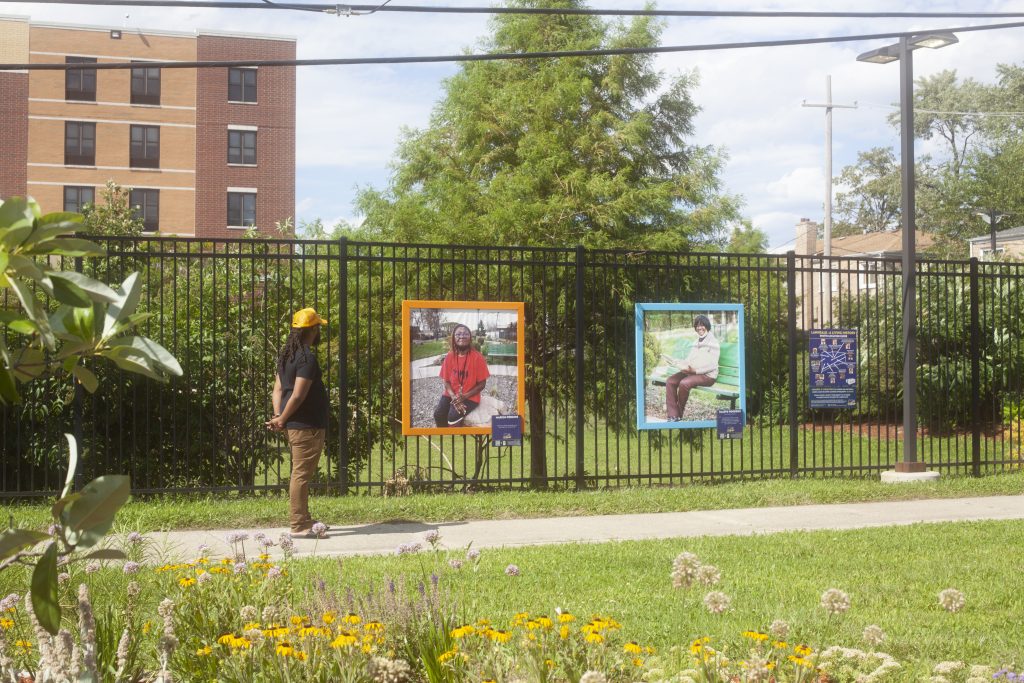

Going into 2020, we had plans to just have this be a short project. We had a couple of other exhibits that we planned on doing. Then, when the pandemic hit, we really had to change gears quickly, so we decided to do only one exhibit, an outdoor exhibit primarily. We had artifacts from the folks that were interviewed for the project and photographed. People wanted to come inside, [the exhibition space/shipping container] but we really wanted people to not have to go in an enclosed space during the shutdown. So, Jay had this idea of doing it in multiple spaces with our collaborators and organizations, a lot of which do community gardening. Even though we don’t collect artifacts, we do maintain our website as an archive with oral histories along with the photos and we will maintain that for as long as we will be around. But it all fell into place. For the exhibition, we were in need of additional funding for the framing of the photos, so the support from The Blackivists felt like it just fell into our laps. It felt sort of cosmic. It felt like a very beautiful and natural connection to be made.

JS: I’m really excited about the fact that we are working with Steven and [The Blackivists] and we’re able to expand on this work with archiving and documenting. Those twelve individuals were so honored that someone cared enough to document their story. The people we document, we call them living legends. It’s like a badge of honor. One of the living legends passed away, Sterling Tate. It meant a lot to me that I recorded him. When I found out that he passed, the [recording of him] just meant something completely different. Like, these were [some of] the last words that this man said and I captured it. It completely changed my mindset about documenting people’s lives.

TH: Diamond in the Back is a collaboration about exactly what you’re both saying, Jay and Jonathan. It is about communities being the caretakers and the keepers of their stories and being the ones preserving that history and culture. One of the things I find most interesting about this project is the range of meanings and ways this project defines cultural preservation and memory work. It offers a wide view of what that can look like, the shape that it can take, and how it can and needs to be flexible and adaptable to certain circumstances, geographies, and situations. Jonathan and Jay, what were the hurdles, if any, that you found once you started actually doing the preservation work? What were some of the challenges that came up?

JS: In terms of the challenges we faced, sometimes it was just scheduling.

TH: That’s real.

JS: We are dealing with seniors. That’s one thing I learned with my mom, when she was still alive — she was one of the living legends still alive during the project. Another challenge was identifying who we were going to interview because there are so many great people doing things in Lawndale and we wanted to make sure that we got people that were active and involved, that were engaged in the community, had history in the community, could talk about it, and that we wanted to give them their flowers. Also, not just elders but [other] community mentors, too. Community mentors just meant that they were in their late forties or early fifties, and we still wanted to give them the respect. But we felt like an elder was sixty-five [or older]. Again, one of those individuals was Sterling Tate. We didn’t know that a couple of months after we did this, he would end up passing away.

Again, a challenge was who to select. Figuring that out, for me, wasn’t just snapping a photo. It was [also or] more so about having a conversation with the individual to get to know them, to understand who they are, what landmarks in North Lawndale mean things to them, understanding their story, having them talk to you a few times. It was about selecting a location that we felt was best, and then the time according to everyone’s schedules. During that process, even with the challenges, and because Jonathan and I are both Aries, we were both determined to make things happen.

I learned that in challenges, there is beauty. It always works out the way it needs to and it sometimes even more than what we expect. We have one thing in our mind, then challenges come and it still turns out great.

JK: Yea, there were plenty of challenges. You know, neither Chelsea nor I are from North Lawndale, although Chelsea’s family does have West Side roots. She, herself, didn’t grow up in North Lawndale. We’ve always approached our work in North Lawndale with an understanding that we were invited in by a community stakeholder. We met a lot of people and have developed and nurtured a lot of relationships, but I’ve always understood myself to be something of a guest. When we conceived of this project, we really wanted it to be a thank you and a love letter to the folks who allowed us into their community, allowed us into their lives, allowed us to connect with work already being done in the community around sustainable community development. Developing that trust and being able to own up to mistakes along the way is always a challenge. It continues to be a challenge. Acknowledging mistakes and having the patience to work on things you might’ve fucked up is a challenge.

Another specific challenge was that in February of 2020, we had decided to structure this with a group of young people and we opened it up to students throughout the community, high school students, to participate as co-curators. We had already done our first exhibit with young people and that was one of the goals of our work — to be inclusive of community members that may be new to curation or exhibitions and to help build their skills.

We had a curriculum and partners. We got a number of people [to participate] and we were paying them. Then, the pandemic hit in the first month of what we were doing. We were only able to have a couple of sessions to build [relationships] because a lot of our students were coming in from other schools. We were just starting to meet at the library and were just trying to build up some I guess, or some sense of connection between all of us; hen the pandemic hit, Zoom was new, and online learning was brand new. So, [it was a challenge] trying to maintain that momentum of what we were aiming to accomplish and with this brand new challenge of students having new technology — if they even had great technology in their home to use to participate — and us not really knowing them and them not really knowing us.

We tried bringing in Peter T. Alter from the Chicago History Museum, we brought in Blanche Killingsworth from the North Lawndale Historical and Cultural Society, and we brought in Jay to teach photography. Maintaining [COVID-19 safety regulations] to create this exhibit was a lot. Some of our plans fell through and we didn’t want to expose the students or elders to COVID. Taking photos outside turned out to be a blessing because of the beautiful natural light and locations.

Another [blessing] was being clear about our expectations of the featured living legends. We were asking them not just to be part of an exhibit, but because these were such large photos and they were going to be in prominent places in North Lawndale, we were really asking them to be exposed — for lack of a better term— and also with the oral histories. We provided compensation, but we were asking people to be raw and personal. We wanted to make sure that they were sure of what we were asking of them and that they were okay with it.

TH: I think the next question is for Steven. A lot of what The Blackivists’ work allows for is self-determination for the groups that you work with — they are the ones making decisions about the histories and materials at every point of the process. It’s the type of collaboration that allows for learning from all sides. We can’t predict what the outcome of these partnerships will be, but I’m curious to know what impact you hope it will have, other than the actual archiving support.

SDB: Each group is so different and the initial conversation, I feel, is always an information session in the sense that we let them know that we value the work they are doing [and ask them what they need]. There is always shock that someone else sees or is able to see the impact of the work, but also shock that we [The Blackivists] want to support what they are actually doing. So, for me, one takeaway would be that organizations know just how valuable what they’re doing is and the need for it to continue. For The Blackivists, I think that’s really all we are trying to do, which is help organizations create whatever self-sustaining documentation program or archiving program that they can in hopes that it does live on beyond us — beyond The Blackivists, beyond the organization.

There’s a lot of relevance and a lot of importance in it, especially outside of traditional institutions like mainstream museums, libraries, and archives. In a city like Chicago, the Black experience, aspects of it, are not documented because those aspects are steeped in respectability politics. There are a lot of people, neighborhoods, and communities that you are not going to find at, let’s say, Newberry Library or Chicago History Museum, if you will. I think that’s what makes Diamond in the Back so dynamic, working with organizations like Lawndale Pop Up Spot, where you have people who are in and a part of that community doing that level of archiving or documentation work themselves, because they see the significance of it without needing an institution to say, “Oh, your stuff is important, let’s keep it here.” It’s always fascinating when you have, as Skyla [Hearn] likes to call them, archives-adjacent people on the ground doing their own work. There’s something really dynamic and significant about that level of grassroots work that happens. You get to keep it yourself and you get to dictate who uses it, who gets access and who gets to interact with it. There’s a lot of power in keeping it in the community versus giving it over to an institution. If nothing else, I just want the organizations to see the value in the work that they are doing.

JK: As somebody who doesn’t live in North Lawndale, but who’s heard a lot about and has seen some of the after effects of some of the Black exodus from the West Side of Chicago over the last several decades, I want to make sure [it’s known] that the archive that we were creating was a sort of living archive. These people have been in the neighborhood and have kept it vital for decades.

One of our projects is an Afrofuturism-connected project, called “Tectonic Black.” One of the ideas behind Afrofuturism is the radical notion that there are Black people in the future and that the future is Black or contains Blackness. I think that’s a specific challenge to the city of Chicago itself, the West Side and North Lawndale in particular…to recognize the current and incipient community that is steeped in history but has an incredible amount of potential. I’m not being as articulate as I’d like to be, but I’m trying to say that the Black community in North Lawndale is incredibly powerful and vibrant.

SDB: Jonathan, I love your answer. And it goes back to what Jay was talking about earlier: the significance of talking to people who live in the neighborhood. I remember growing up and there being plenty of elders on my block. As a thirty-something-year-old now, I wish they were still living and that I could ask them all the questions, just to know what their childhoods were like, their upbringing, and their Chicago experience. I think what makes Lawndale Pop Up Spot, especially this project, so beautiful is that you are capturing those conversations now and these people are now written into history. I think that’s so fascinating and it’s a really great model for how we can cultivate intergenerational conversations within neighborhoods. It would be really great to see more of that across the city.

JS: That’s a great point, Steven. One of the things that [didn’t happen because of the pandemic], we were going to do intergenerational conversation with the elders, community mentors, and the youth — and have a conversation with the Chicago History Museum. Steven, you are so right about seeing the conversation between generations. Having that is powerful, so hopefully we get a chance to continue that work and do something like that in the future.

TH: I think all of you said something about the future in some way, shape, or form, so speaking of the future, what is coming up for all of you, whether it is near future or far future?

JK: Lawndale Pop Up Spot is not bound by only being one thing or another, and we like to mix up our exhibits by having some art, something experiential, and some history. I’m really interested in a couple of historical projects, exhibits and explorations including one about the Art & Soul community art space that was opened up in the 1960s by the Conservative Vice Lords.

TH: Yes!

JK: We were brought into North Lawndale by Benneth Lee who had done an exhibit with Jane Addams Hull-House Museum around the Conservative Vice Lord experiment that included some panels and documentation from Art & Soul, but didn’t really get in super, super deep. I would love to see us as an heir to that model, but not quite in a lot of ways. We are in our Afrofuturism summer now, we’re doing a lot of exhibits and events exploring the notion of time and thinking of future and past as not being distinctive as we’d like to imagine. There are circular notions of time in different cosmologies. That’s been fascinating. Sojourner Zenobia has been leading that effort for us this summer. Then, this fall, we are collaborating with an architecture firm called Could Be Architecture on a sukkahs design project.

Sukkahs are structures created for the Jewish celebrations of Sukkot. They are temporary structures where people in the Old Testament would need a structure to stay in when they were in the harvest. Joseph Altuler came up with this idea of sukkahs that could be in service to community stakeholders, and because North Lawndale has a rich past Jewish history, much of the architecture in the community— especially the larger buildings — were Jewish synagogues, orphanages, or other community spaces. We decided to collaborate with them and teams of designers to do three sukkahs. Each will have a different home after they are done and they will be community designed.

One of our partners, Stone Temple Baptist Church, is going to have their sukkah be part of their historical museum of the church. So they will be bringing in their own archives and finding interesting ways to display them in this structure. There might be photos or maybe some video. Stone Temple is where Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke and where Mahalia Jackson sang [in 1966]. A lot of really notable figures have come through those doors, so it’s exciting to see how this project may connect with some of that historical work. Reshorna Fitzpatrick, the associate pastor there, has a passion for exploring and showing off history. That’s part of what our future holds.

JS: Right now, I’m working with the Lawndale Pop Up Spot, Stone Temple, Lincoln Park Zoo, and a youth council on a nature photography project. I’ll be working with fourteen to nineteen year-olds and co-facilitating with Jaeda Branch, the program lead from Lincoln Park Zoo, to teach how to tell a story through photographing nature and horticulture. When I photograph nature, it’s peaceful. It helps relieve my anxiety. It’s something that I look forward to. It’s pleasant. It’s serene. Plants are not like people: “can you get my good side? I look ugly.” They’re just in their natural state of beauty.

My goal, always, anytime I’m working with young people is for them to take hold of that. And maybe go to the park to take some photos [if their] anxiety is running high. Maybe they will just find interest in it as a hobby or career. Also, projected for 2023, is an event for an exhibit called Black Exodus. As Jonathan mentioned, my dad also used to talk about how before he migrated to the West Side, North Lawndale was filled with nothing but Jewish synagogues. In the morning, he would wake up for work and he would hear them in the temple worshiping. At that time, people migrated out of the neighborhood to other places and the city started changing. At one time, North Lawndale was a thriving business community and then the riots happened and all those businesses either moved away or they never reopened. It would be interesting to try to find the individuals that left to see why they left and if they heard the stories of [when] the Jewish and Black community were close. Another individual that I interviewed was Edwin Muldrow, the owner of Del-Kar Pharmacy, which is a pharmacy on 16th Street. It’s been in the community for over thirty years. Edwin’s father started Del-Kar, and his business partner was Jewish. He told us these stories of how a lot of Jewish people were working with Black people and things of that nature. When Jonathan said it would be really cool to see if we could find some of these people and get these stories, I really liked [the idea].

TH: Steven, I know the future of The Blackivists is another year of Diamond In the Back, but is there anything about the future of this project or other projects that you want to mention?

SDB: We are getting ready to resume our workshop series in the fall. Our workshop in September will be on grant writing for small collections and will be taught by Andrea Jackson Gavin from the Atlanta University Center at the [Robert W.] Woodruff Library. At the top of next year, we will have our two final programs, one on digital preservation and the other on activating the archive and how to engage the public with their material. Then, I think The Blackivists are just continuing to work with groups and trying to dream up what the next iteration of Diamond In the Back may look like and the next iteration of us as a collective.

TH: So, last question — a kind of love letter question: What is something that made you fall in love with the West Side or keeps you falling in love with the West Side?

JK: This is specific to North Lawndale and a complete matter of happenstance. Chelsea and I happened to be friends with a professor at UIC, they came to us with this project, and we just kind of fell into North Lawndale. But there’s something tangible in the air around this historical space, it’s also a space of possibility. Part of North Lawndale is called “holy city” and, to me, there really is something almost spiritual or magical about the space that we’re in. When I look back to six or seven years ago and where I was after the library world, I had no idea where my life was going or what direction it would take. I didn’t even know I would [end up] in Chicago, and I’d never set foot in North Lawndale to my knowledge until that point. Everything has felt like it has just fallen into place. It’s like walking down the street on the yellow brick road — bricks just keep appearing in front of me as I walk. I feel like Diana Ross in The Wiz. It’s not anything that I can put my finger on specifically, it’s just this feeling of the ever-present possibility and almost like the inevitability of the work that I’ve done so far.

JS: My love for the West Side and what draws me to the West Side is the whole family element. The whole concept and notion of the village, you know, how it takes a village to raise a child. I actually lived that growing up. If I did something, one of the neighbors would say something to me about it, tell my mother and tell me my father. I had to go through all of these different people who cared. I see that a lot. I see people having a good time with each other, no matter what their culture is. I see those things as an element of the West Side.

I also did a documentary project where I was photographing buildings that were personal landmarks to me or just in the neighborhood of North Lawndale. I photographed the building across the street from where I lived. I found out more about this history because I collaborated with an architecture photographer — I ended up finding out that it was one of the houses that Al Capone’s brother had. I used to sit on this porch all the time.

The West Side is like a family, North Lawndale especially because of the deep, rich history. I think that people who know the history, they take that on as a badge of honor, like pride. They galvanize around being from North Lawndale with such passion because they know the history, the people that were here and that lived here, that served here. Those are the things that keep me tied here: the people and the people I’m collaborating with. Everyone here shows me love, it’s like a family.

TH: Steven, what about you?

SDB: That’s a great question. For me, it would be the diversity of the West Side. I was fortunate to go to an elementary school that was Black, Puerto Rican, and Mexican, and we had a couple of Polish students as well. And that really informed my way of thinking and who I am now as an adult because I’ve always gravitated to culturally diverse neighborhoods. Being back and having this adult experience, I’m driving through the West Side and seeing how much things have changed or have not changed. One thing that has not changed is just the diversity of the West Side. I absolutely love that, especially after living in cities like [Washington] DC and Atlanta, and seeing how people and cultural heritage are being pushed out of these neighborhoods. But it seems like here, on the West Side, folks are not leaving and I absolutely love that.

TH: Anything we didn’t touch on that you would like to mention?

JK: I just want to send out a huge thank you to The Blackivists and the legends who sat down and agreed to share their lives with us, as an organization. It was a really big ask and the fact that they were enthusiastic about it, that’s a gift that I’ll never forget. I just want to give them a shout out. And, of course, Jay, who is a tremendous partner and we are excited to work with him whenever we can.

JS: I just want to say thank you, Tempestt, for getting us on the phone and asking us these questions. At least for me, sometimes it’s a reminder of the work that I have done and what I’m doing. I just get so caught up in the work that I don’t take a step back to have a conversation about the work. When someone comes in and asks questions, you can reflect and think, “wow, we did that in the pandemic! I completely forgot about all that.” Do you know what I mean? You’re not [reflecting on it] while still continuing to do it because you are in the work, right? Jonathan and I are very determined to make things happen. Our imaginations are big and then we have to scale it down.

JK: We really do. At one point we were going to project these images on the Sears Tower and we consulted with somebody like, “How do we do this?” And they were like, “you only have a thousand dollars, Jonathan…”

JS: And I love that. You know, Jonathan always pushes the envelope and I’m always willing to rise to the occasion and get it done. Obviously, you can tell that we enjoy this work. I enjoy documenting, telling people’s stories. Everyone has a story to tell, just not everyone has someone to [help them] tell it. So, anytime I am able to do it, it is always a pleasure. Thank you, Steven, for the work that you are doing and the collaboration work.

TH: Well, I just want to echo what Steven said earlier: you’re doing the work, we just want to uplift it. The work that I do wouldn’t exist without this kind of work, so I’m grateful to the three of you for everything that you do. Sixty wouldn’t exist without work like this, so thank you.

This interview is presented as part of Diamond in the Back: Excavating Chicago’s Black Cultural and Material Heritage, a two-year community archiving collaboration between Sixty and The Blackivists, a collective of trained Black archivists who prioritize Black cultural heritage preservation and memory work. Diamond in the Back is made possible through a wide range of resources, including support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

About the Author: Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com.

About the Photographer: Samantha Friend Cabrera is an artist and writer based in Chicago.