This article is presented in conjunction with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art that seeks to expand narratives of American art with an emphasis on the city’s diverse and vibrant creative cultures and the stories they tell.

on the occasion of Ruth Duckworth: Life as a Unity *and her three large sculptures Spirit of Survival, Serenity, and Earth, Water, Sky

though innocent

of what is born

bits and pieces

but never the whole story

what we are

we are at the hands of the universe

to which we cling

precarious

random1

Dear Ruth,

Hello, from many moons away. I read somewhere that you enjoyed sending long letters to friends and students, so I thought I’d return the gift. While you don’t know me, you might remember the same vibrant enthusiasm from the tongues of your students or at the tips of their fingers, ready to pour themselves into making whatever preoccupied their aesthetic wonderings. And as I write this, I find myself with this same curious excitement. Curious because, in part, writing this letter is a Sisyphean task—a loving eulogy that will never receive a response.

Put differently, focusing on a letter back from you feels misplaced like trying to use Untitled (Mama Pot) as a container for water. This intimate work teaches me many lessons about the fallacy of closure. In lieu of utility, a jagged cleave pierces through it, and its constitution of use becomes less important than its biomimicry of fragmented volcanic or oceanic landforms. It may hold water for a little while like the way that a conch shell holds water—with majesty and mystery that shifts your notice from the singular to the plural. You give new meaning to hollowness. The integrity of closure is ambiguously porous, you continue to teach me this through the elliptical bodies of large and small works left in place of your physical absence.

On the second to last day of Virgo season, your retrospective opened at the Smart Museum of Art. Productivity and potential of all things fume the air. Your work hasn’t lived together like this since 2005, congratulations! They named it, Ruth Duckworth: Life as a Unity, after your proclamation “I think of life as unity. This includes mountains, mice, rocks, trees, women, and men. It’s all one big lump of clay.” The speculative coalescing of this statement, likens the experience of a mountain to that Of Mice and Men, suggesting the planetary scale of time that reverberates through the chambers of your heart.

The ungraspable cosmic tremor in your works offers a speculative lens of the mundane which attracts and disturbs me. The range of architectural attributes each vessel offers accentuates your desire to experiment and derive inspiration from materiality—both in your media, stoneware, and porcelain, and how it shows natural processes like topography, cloud formation, erosion, and mimicry. Your earthenware gives shape to impermanence and ambiguity—bending, beating, carving, and sculpting soil. Each action arcuates the beauty, mystery, and violence found in how the material is created and extracted. Persistently questioning your role as an artist, in our state of ecological disaster, uncovers a commitment to finding unexpected synchronicity in otherwise unalike parts. I admire this. Screaming hues of patina, reposed cathedral imagery, and geological ripplings hold together a rich vocabulary of forms adding dynamic registers to your visual language. From the more oracular pieces (e.g. Untitled, 2005) to the more sleek porcelain outputs (e.g. Untitled, 1992), immanent alchemy summons all of the works as they imbibe, collapse, and dissolve into one another. Another kind of Unity.

I find the refrain of your work to ruminate on exchanges of ideas, perspectives, and empathy. I wonder, what is the exchange between your work and your teaching practice? The otherwise and the unnoticed. You had an everlasting desire to learn and teach. As a practicing artist, educator, and learner, I believe in this same continuum—we all have something to teach and to learn. I hoped to learn more about the exchange between you and your students, as a site that informed, or possibly inspired, your output. With so much consideration of new, art historical framing of your work, your identity as a teacher was overshadowed. You once said that “large things interest you,” so I searched for all of the “large things” your hands made. Coincidentally, I learned that all of what you made in various locations in the state of Illinois lived on college campuses. Already interested in your devotion to education, I wanted to learn about your relationship to academia and the “large things” that followed in your path.

I began with Spirit of Survival (1998).

Evident in the name, there is a spiritual quality that emanates from this zoomorphic form. Spirit of Survival lives at the Lewis & Clark Community College in the Monticello Sculpture Gardens. Its materiality and placement refract the sunlight perfectly causing it to shine as a beacon. Metaphors of aviation and the idea of destiny take root in the abstract body articulation of the Spirit of Survival. The bronze giant is no longer meeting my gaze from a loving distance but is now towering over me with a dominion of quiet, looking beyond to a horizon that I can only speculate. Our two architectural bodies, two symbiotic bodies:

seeing,

meeting,

sensing,

eclipsing,

touching,

dwelling,

collecting,

slipping,

mimicking.

It wades in the grassland by the water with a heron-like head and an enclosed archway body made of hollow bronze. Its curvature mirrors the circumference of Martin Puryear’s work. A friend echoes this sentiment and I smile, having just read the forward he wrote about you in a tea-ring-stained, second-hand book on my kitchen table.

The sun has moved several paces to the West, I rest

on a shoal

a graceful, supple surrender overwhelms me

I begin to d i s a p p e a r

Under its shadow

Octavia Butler tells me that what you touch, touches you and Beatriz Santiago Muñoz says, “Sensing, experiencing the scale …. It is a matter of resolution, of detail and scale, of identification—an understanding experience not through a lens, or a text but through physical apperception.”

Is this the unity you imagined as a teacher? Understanding your students’ experiences through detail, scale, and relationality: touching and being touched? I wonder how they talk about your work during group tours, class visits, and lectures. Do they know that this sculpture monuments the egrets you observed during the 1993 Midwest Flood? Do they realize that egrets are communal creatures constantly rubbing up against each other and building nests en masse towering to scrape the clouds?

Spirit of Survival is encircled by the works of Richard Hunt and Magdalena Abakanowicz. I reflect on how that triumvirate feels like the friends who ventured with me to see your work. I relax, sensing that maybe we’ve made a unified composition of our own in Godfrey, IL, and that maybe this is the Unity you imagined.

I must say, generally, Unity is a prickly word for me. Its meaning feels unattainable, flattened, and neutralizing. A language that fails to give distinction and totalizes difference. As an educator, I often encourage students to lean into uncomfortable and complex wonderings, so I took my advice. During my ride on the 82 bus to visit Serenity at Northeastern Illinois University, I played a game:

I asked myself;

What Unity can I find on my bus ride from the Southside to the Northside?

I answered myself;

hands holding, baby on hip, shy smiles, “tell her I said hi”, the smells of hot grease, lemon pepper, unity park.

Serenity speaks the vocabulary of totems and anamorphism. Two schorl-colored figures sit on a podium—unassuming and in waiting. Punctuating the space above their heads are two divergent birds, one: a cool and tempered bald eagle replica and the other: a ubiquitous bird in flight. This work sits solemnly and exalted in the middle of a grassy field. Your animation of figures, at once imaginative and ancient, recast a human future that refracts non-human directives.

Is this where I find serenity? On the level of an egret’s nest? Or in the clouds like our avian friends?

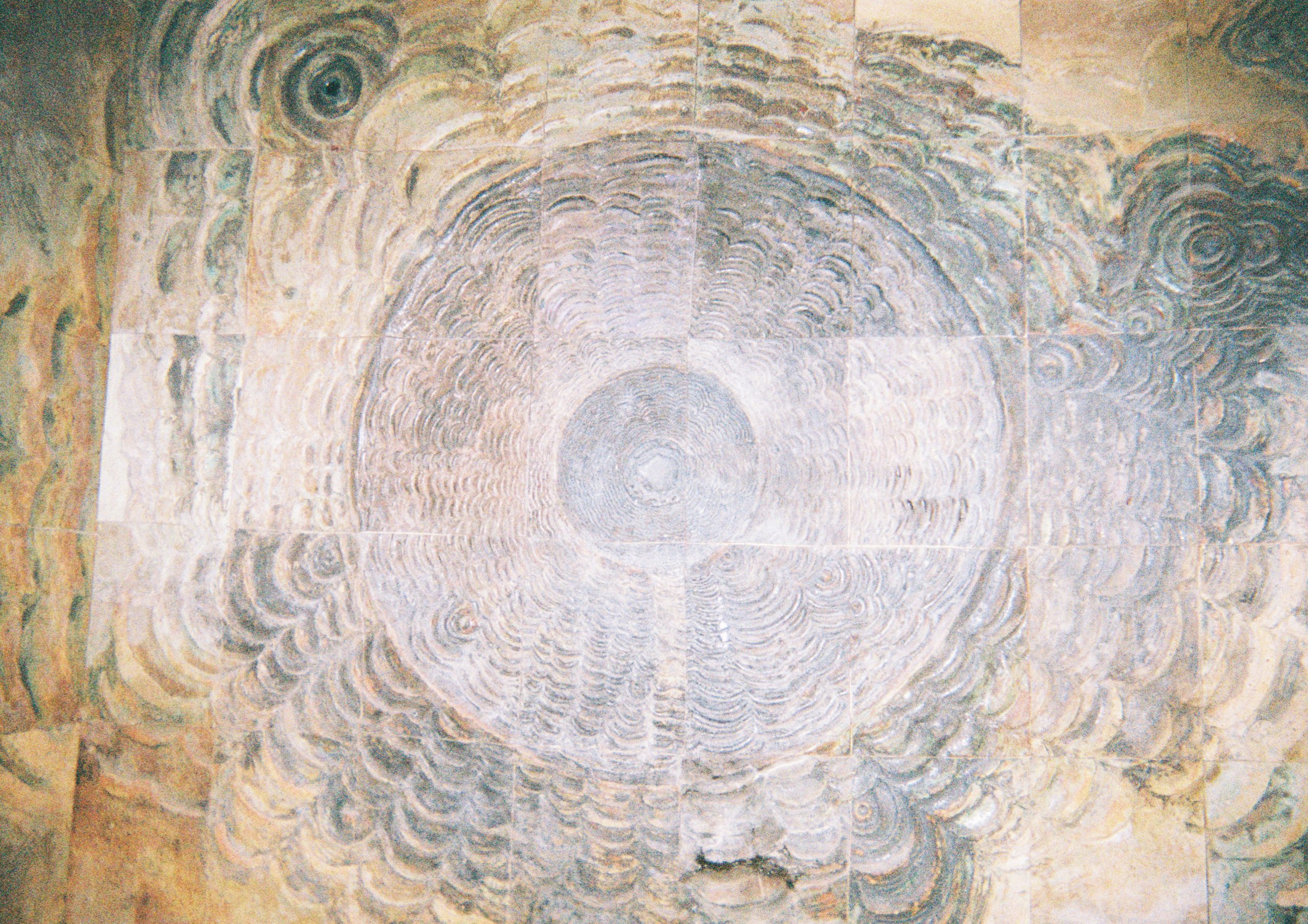

I end my journey in the vestibule of the Henry Hinds Laboratory for Geophysical Sciences on the campus of the University of Chicago. Going into the life-size maquette of Earth, Water, Sky feels like wandering into an active sinkhole, it vibrates with the sea of students rushing through it to get to their classes. I am subsumed under this turbulence. Do they know what they brush past? There is a sonic elemental expression that ripples and protrudes from the walls, reminding me of keloids or the insides of a whale where ambergris is made. A sweet surrender cocoons me as I think of being eight years old and traveling to Luray Caverns with my family of three. My fingers swept the walls as we walked, wanting to save every single grain of dirt under my fingernails.

I made sure to touch every surface then and touch every surface now. My fingerprints are shiny. I left some behind on Earth, Water, Sky. I hope you don’t mind.

I began this letter as a place to explore the belays of your work to your teaching practice, a burning question of dedication to education. I admire my initial vigor. Gloria Anzaldúa reminds me “You’re aiming not for a linear, logical structure of ideas but, instead, for an architectural body that supports and allows access to its innards.” And Ruth, you’ve shown me some ins and outs that aren’t necessarily congruent but importantly unified. I suppose that is the point. What will stay with me forever is the inherent vice of your public works. Each sculpture, though stout in build and presentation, has visible deterioration with whispers of entropy. Each one shows signs of weathering and survival, reflecting our collective temporal circularity.

Answering a question about your approach to craft, you said, “It is a temperamental material. it wants to lie down, you want it to stand up. I have to make it do what it doesn’t want to do. But there’s no other material that so effectively communicates both fragility and strength.” I realize that you’ve always chosen a bricolage path, one that stretches, expands, and rearranges a vast archive to show the apparitions of the land, to whatever end. You’ve resisted easy assembly for what seems like your entire life and I cannot help but think that this attitude must have seeped into your pedagogies. An attitude of fragility and strength.

Until again,

Isra

* * *

Ruth Duckworth: Life as a Unity is on view at the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago from September 21, 2023 – February 4, 2024. The permanent installation of Spirit of Survival is located at Lewis & Clark Community College in the Monticello Sculpture Gardens, Serenity at Northeastern Illinois University, and Earth, Water, Sky at the Henry Hinds Laboratory for Geophysical Sciences on the University of Chicago.

About the author & photographer: isra rene is a curator of care weaving webs of dreams tufted by our inherent connections of love, vulnerability, and care.