“…historically, we were seldom invited to participate in the discourse, even when we were its topic.”

—Toni Morrison, The Site of Memory

In one of my all-time favorite talks by Toni Morrison she speaks about what she calls the “interior life” of Black folks, also known as the distinctly Black experiences, thoughts, and emotions that oftentimes go unseen by the rest of the world and are usually excluded from historical narratives. She goes into depth about how this is usually an intentional omission, particularly from the narratives of those enslaved during the 18th and 19th centuries, because those stories were usually constructed or edited by white people, or intended to be read by white audiences. The concern was that if those readers really knew what Black people thought or went through, they might not be able to handle it. As a result, the interior thoughts and more monstrous accounts of that period were glossed over or given a “veil,” a covering that Ms. Morrison worked to remove through her novels. She explains that, “the absence of the interior life, the deliberate excising of it from the records that the slaves themselves told, is precisely the problem in the discourse that proceeded without us.”

Today, as we settle into a swelling movement that is annotated by relentless public access to people’s internal thoughts and a growing level of fragility in response to grisly elements of Black Life revealed, there are still experiences and personal accounts from those at the center of the fight for Black liberation that struggle to be seen.

Brayla Stone, Dominique Fells, Riah Milton, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Nina Pop, Oluwatoyin Salau, and the list goes on.

Testimony is an earnest attempt to address this by offering and archiving a series of essays, interviews, and first-person accounts of the interior lives and exterior experiences of Black trans, Black women, Black femme, and Black non-binary artists.

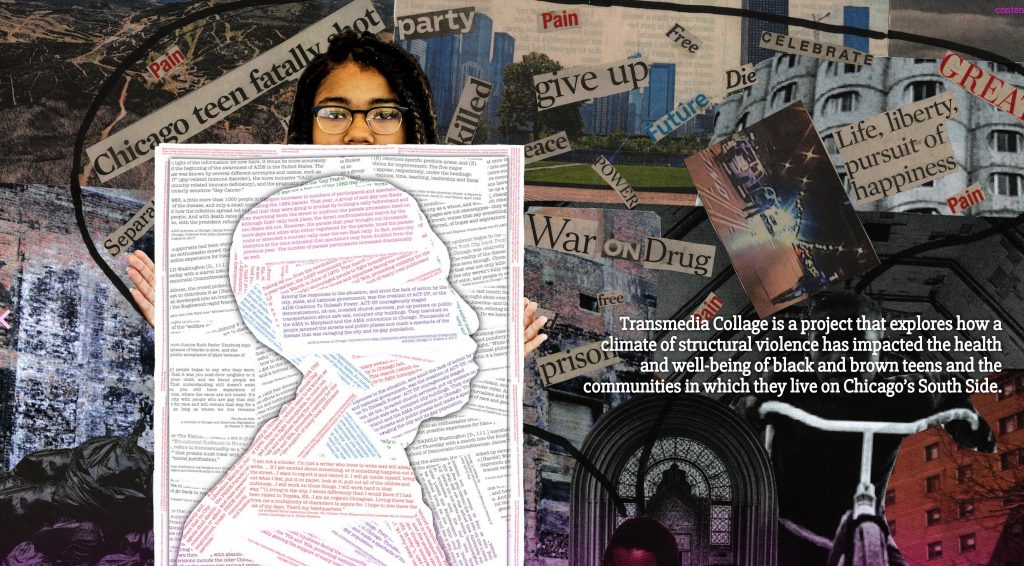

A few weeks ago I spoke with Ireashia M. Bennett, a Black queer new media artist from Suitland, Maryland who now calls Chicago home. Their work takes the form of photography, multimedia essays, short documentaries, and experimental films that poetically harness and affirm Black queer disabled perspectives and realities. In our time together, we discussed the importance of a clear and unapologetic artistic intention in this moment, the need for more tenderness, and how there’s a Nina Simone song for all occasions.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tempestt Hazel: This is a strange time to be having a conversation, but I think that it is an opportunity for reflection. We’re in a special kind of moment and also a complicated time for film and photography, all of the documentary art forms. So, I would like to start there, with your work, and hear from you about what is on your mind in relation to your practice right now, and how you define practice.

Ireashia M. Bennett: I am a photographer. I love documentary photography and portraiture. And I am a filmmaker who does a lot of work around Black queer realities and experiences. I’ve done work that centers around trauma and healing from trauma, because I feel like—as is the case with any artist—whatever I’m dealing with at any point, that’s what the work is about. And I feel like trauma in my family is so deep and layered, like in any family. Sometimes it feels overwhelming. I’ve been doing this type of film and photography work for about five or six years. And my ultimate goal is just to be a dope-ass filmmaker and to make films that are accurate depictions of Black diasporic life, along with all of our joys.

I just received the Spark grant (from Chicago Artists Coalition)…

TH: Congratulations!

IMB: Thank you! I’m also interested in DJing as a form of storytelling, so I’ve been teaching myself DJing as well. The next phase of my artistry is to combine visuals with DJing sets to create a cohesive collage-esque work of art that speaks to a narrative, feeling, or experience. I think this moment—the pandemic and uprising—has encouraged me to define more concretely the ideologies and frameworks that drive my work. In the past, I kind of knew but didn’t really know how to communicate my political thoughts. But now it feels necessary to let people know up front what I’m about. I’m all for Black Trans rights. There’s no room for vagueness right now.

I’ve been reading many books and learning more about prison abolition. I’ve been trying to think about what my place is in this work of uprooting and dismantling racial oppression and gender oppression and systemic violence. And my role as a storyteller and visual artist is to make sure that these frameworks and ideologies are accessible, and to use film as a means to make sure all people understand [these ideas]. So, you don’t necessarily have to read Angela Davis to know what prison abolition is.

Another thing that’s been coming up is the fact that I knew before this moment that I believed in prison abolition but because I didn’t have the background and didn’t take polysci classes or read all the books, I wondered if I was really this radical. Is my politic really that radical? Is it an elitist thing? The thing that’s [communicated] in academia and sometimes organizing culture is that if you don’t have all the words or all the language, then you don’t really know. And my way of breaking that down is to use film, which is more accessible I think, and to use visual art to communicate and translate.

TH: There’s so much you said there that I want to dive into. First, I want to go back to what you said about how you use film and storytelling as a way to make different ideas more accessible. I think that’s so important. And I’m really excited about the different interpretations of these ideas and the ways that art can be used as an educational tool—which it always is.

I also want to speak to your other point. I don’t think you need to necessarily read the books or take the classes in order to know what you believe. Though, of course, reading and learning is important. I, too, feel the same way. I’ve read some but definitely haven’t read all the books. All the definitive texts. But, I think about how I’ve internalized my understanding of abolition and liberation right now and over time. And I think about the moments of incredible joy as we’re seeing things move to this new place. And while a lot of things are weird and messed up, we’re at a place where all of us who are feeling this and seeing these ideas put into motion. Many more people are feeling like this is our time, and that we’re arriving at this place of possibility—we haven’t arrived, but we’re getting somewhere in a way that we haven’t in a very long time. Wherever you’re arriving at these ideas from, I think all of us have to continue to find our footing in this movement, whatever our footing may be. There are so many ways to be Black in this moment—in all moments. And what you’re saying about finding your place as a storyteller and finding your role is important. I can’t speak for everyone, but I know I’ve been doing the same thing and working to find my footing. To find what my role is, and a role that makes me feel good while recongnizing that there’s a need to be impactful and also listening to what is needed. Navigating both of those things is necessary.

So, then how did you get to a point of clarity in knowing your role at this time, as a storyteller?

IMB: Really, it’s just FOMO—of not being able to protest in the streets and knowing that we’re in a pandemic and I am still very much so immunocompromised. I can’t be marching in the streets and showing up physically. As a person with chronic illness, when I supported artists or exhibitions, I couldn’t always be there physically. So, this moment I have to work through my shame and guilt of not being able to show up physically to protest. [Instead] I’ve been sitting down and talking with my friends, and asking “What can we do?” What makes sense for me? What is natural for me? How can I incorporate a sharper and more focused political framework on what I already do so that I can be more pointed and clear on what my position is and how I want my work to exist in this world. So, yea. FOMO.

TH: That’s the truth.

IMB: There’s so many different types of work to do. I also feel like protesting is glamorous—to be able to say, “I was there!” And [as a photographer] I always want to have that photo. But that’s not a myth, but….

TH: Romanticized, maybe?

IMB: Yea, romanticizing what this moment looks like.

TH: I was trying to think about how to bring this into a conversation, but I really want to thank you because you’re the reason I ended up re-starting and reading Heavy–because about a month or so ago you mentioned you were reading it and Thick. And I realized that this would be the exact right book for me to read right now. I bring it up because there is a line in the book that said something about not romanticizing the revolution or movement, which stuck with me. So, what you’re talking about is really something for us all to think about. We need to make sure we don’t get lost in feelings of inadequacy because everyone has a part to play. We just have to make the effort to identify it. I really appreciate you saying that because I’ve been struggling with that right now as well. And similarly, me not being able to be in the streets makes me feel some kind of way—there is guilt and shame with that. There’s a desire to support my people and the things they’re organizing. But there’s also something nice about coming to the realization of what my lane is and what I can contribute, which is just as important as everything else. Because this moment isn’t about hierarchies. It’s about getting the work done.

IMB: Right! There are people feeding people. There are artists painting the boarded up buildings with murals. There are so many ways to bring joy into this moment and to not get overcome by grief.

TH: I want to ask you another process question. Can you talk more about the language that you use and how you refine the language? What was the motivation for starting to do that work to better articulate your intentions? And where were you at before coming to that realization?

IMB: Before, I wanted to do visual art that celebrates Blackness—and everyone says that. It’s not a very [specific] thing. And I’m at the point now where I want to make something meaningful for those who are disabled, chronically ill, Trans, elderly, Southern. I want to create work that isn’t universally felt, but understood in different ways. I’m still forming the language around my work. I want to be mindful [of the fact] that my audience isn’t all Black people. It’s my grandma. It’s my mom and younger siblings. I want to make sure that when I create work that they can understand it. That’s really important to me. I’m not doing conceptual, abstract work that doesn’t have a specific tangibility to the lives of everyday Black folk.

Also, I want my work to reflect the messiness of trying to unlearn white supremacy, anti-blackness, and fat phobia or ableism. And do it in a way that isn’t shaming. We all have internalized anti-blackness and it’s a process to unlearn it everyday.

I came to this moment because I want to stand for something. I want to make sure I know why I do what I do and what I do this for. When I remember that—when I know what my work is grounded in—I can move with so much clarity and it feels like I’m not trying to be everything to everyone. Instead, I’m talking about the things that people don’t want to talk about, like trauma, familial sexual abuse, fat phobia, and desirability politics. I want to talk about those things in a way that is emotive, soft, tender, complex, and hard. And doing it through film, audio, voice, music, and collage. Blackness isn’t one thing. It’s an amalgamation of many things. Of generations. Of so much. There’s no one way of being Black. Growing up Black American, we [are told] to be a respectable Black and [pull ourselves up by the] bootstraps. But now we’re even trying to eradicate those ideas.

I also want to bring more tenderness into the world. You know? I want people to look at a photo of mine and feel held. Or walk away from one of my films and feel seen. I want to bring my empathy and care into the work I do. And I think that’s radical. Black women, femmes, Black Trans women—we need tenderness. The world wants to break us down and literally kill us. We deserve to be held in so many different ways.

TH: Who does work that has the kind of tenderness you’re talking about.

IMB: Ja’Tovia Gary, Tiona Nekkia McClodden. Music wise, Frank Ocean. Alice Coletrane…

TH: You’ve also been thinking about these immersive experiences that combine sound and visuals. And when I think about some of the most transformative experiences I’ve had, they’ve been multi-sensory experiences that you can just lose yourself in. It makes sense that you would be going in this direction.

IMB: …another song that keeps haunting me is Nina Simone’s version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” It’s instrumental. That song takes me places.

TH: It’s almost like any Nina will take you all the places. To me, she’s one of those timeless artists. The power and clarity of her as an artist and as a person gives her a kind of perpetual relevance. She will always be relevant, for the rest of history.

IMB: And the emotional range of her discography is mind-blowing. There’s a Nina song for every mood. Feeling melancholy, Nina got you. Feeling angry as hell, Nina got you. Feeling like you want to fuck, Nina got you. I can’t stop singing her praises.

TH: I want to shift the conversation and ask you a question that’s basic, but is also one of the most complicated questions people are asking right now: How are you doing? How are you doing spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and politically?

IMB: That is the question. My mood changes every week. When the pandemic started, I was consumed by loneliness. It was so hard to do anything. Not knowing when I was going to see my friends next or what is happening in the world. I was feeling tired, lonely, and sad. But I was also shaming myself for feeling these ways in the middle of a pandemic. So, that was all of March and April.

But I’ve been committing myself to spiritual practices like meditation—even if it’s just 10 minutes a day, in front of my ancestral altar. Meditating, talking to them, cursing them out if I need to. Telling them where I’m at. Because I live alone, I don’t have anyone around me to call on when I’m sad. I also feel self-conscious for being needy sometimes. My ancestors are there for me. And my loneliness has really diminished since I’ve been doing that every morning. I’ve been sitting with them, bringing them coffee, talking shit with them—it’s been so good. It has shifted something in me. It reminds me that I’m never alone or walking this earth devoid of another presence around me.

I’ve also been able to show up for myself in ways that I hadn’t been before, because not only do I have to, but I want to. Before March I was thinking of all the ways I need to show up for people emotionally or physically. Show up at my job. Now, I’m thinking about what I need each day and what makes me feel good. What does my body feel like? It’s been filling me up.

I still have my lonely days and days when I’m angry or listless or overwhelmed as fuck. But it’s not debilitating anymore. And I’m proud of that.

TH: Loneliness isn’t something that you get over and it’s done. It’s a constant battle. But when you feel like you hit a nice point in that battle or some success in that battle, it’s definitely worth celebrating. Because a lot of people don’t find success in that battle or don’t even know that’s a battle they’re fighting.

But what you said about being needy. I don’t want to necessarily ask you to unpack that unless you want to, but that is something that I definitely identify with. I’ve been wondering lately where we can be vulnerable or needy. Needy even has a negative connotation to it, so is it even the right word to use? What does it mean for us to just need other people? Human nature is to want to be around people. And, to me, that’s what’s the most exciting part about right now. Folks are seeing racist actions and harmful thinking exposed, and the racist things they aren’t aware that even they do.

What I’m unraveling are the different ways that I’ve internalized white supremacist, capitalist, or other ways of thinking that have caused me to feel certain ways, usually negative ways, about things that should be considered natural and human. Like being needy. What does that mean? And by whose definition are we considered needy? Because we, in fact, need one another. We need our ancestors. We need these things. And for me, unraveling some of those things has been the lesson. That has been part of the work that I need to do: to release the shame that has been placed on our human qualities and natural ways of thinking. To release myself from these very cold and corporate ways of thinking, and not compromise what I know in my body to be true, which is that sensitivity and intuition is a strength. Vulnerability is a strength. These are the qualities that allow us to bring our full selves into a space. Especially in a time when the idea of “bringing our full selves” into a space has been co-opted. Almost no one in those spaces, especially what are considered professional spaces, actually want you to do that.

You and I are both at white institutions with long histories. I don’t think they actually want us to bring our whole, full selves into their spaces.

I say that all to say that unpacking how we define ideas like neediness internally versus externally, whether for ourselves as individuals, our professional selves, or within our communities is something I’m interested in. And getting to a place where we’re not telling ourselves, even in quiet and subtle ways, that this is the wrong way to respond. So, I find it interesting that you said that.

IMB: Thank you for going back to that. I think I was referring to being codependent and being so reliant on another person that I don’t have a sense of self. But I do think part of my embarrassment around this is that people are seeing me in these vulnerable ways. Like having an anxious spiral. In April, I started reaching out to the people I trust with my fullest feelings and asking them to send me love and affirmations when I have a really bad day where I’m still in bed at 1pm.

I’m starting to realize that me being “needy” is just me needing people. It’s not codependence or relying too much on anyone.

I mean, this is some unprecedented shit…

TH: That’s the word of the year…unprecedented.

IMB: Everyday I’m like, “What’s about to happen today?” Because I know something’s about to pop off. No day is normal now.

My friends and I have been talking about the fears, shames, and insecurities we’re shedding because they just hold us back and hinder us. I’m looking forward to what 2021 or 2022 will bring. There are going to be so many people showing up more authentically, being more honest, and showing up more because fuck fear.

TH: Do you think the world is ready for that?

IMB: They have no choice.

TH: It’s true, it’s coming. You either accept it or you don’t. You might not be ready, but you have to accept it.

IMB: I also think some of the people who are older and enjoy how things have been, they won’t be ready. Saturn is going to be in return. This is a time of change. Change is coming, change is here. I’m here for it.

I’m also learning how much friends and community matter to me. I can rely on people to show up, check in on me, and make sure I’m good. To go get groceries. Care work has to show up. Love has to be tangible right now. Anyone who is not giving love and you don’t feel that love, I can’t show up for that. I don’t want friendships built on pleasantries, or performance, or clout. I don’t want friendships with people who can’t show up for me. Not that you can’t have acquaintances, but you need real people in your life. I’m learning what that means for me.

TH: That’s so essential. And recognizing that our friendships may shift and change a lot right now is important, too. Some people might reveal themselves to not be the right people for this movement or the future moments we’re creating for ourselves. And that’s okay. Some old friendships may be dusted off and recharged right now. And that’s okay, too. Like you said, change is happening.

So, I feel compelled to ask this question because of the ways that Black women, Black Trans women, Black femmes have often been made to feel invisible to the world outside of ourselves, especially our experiences as they relate to this reckoning of anti-blackness, systemic racism, and daily racism that we have to deal with. Also, I feel the need to ask because of the ways Breonna Taylor’s story or other stories of Black women and femmes take a back seat or have to fight for visibility in people’s consciousness. Every time a Black woman or Black Trans woman is killed, I feel some kind of way about what feels like a fight for visibility. A fight to be seen. Recently, I’ve had several moments where I’ve wondered about how we can do things differently now and not repeat what we hear about often when it comes to the movements of the 60s and 70s where women’s stories, names, and contributions were neglected or erased from the accounts of those movements. Uncovering those histories has required decades of excavation—usually by other Black women.

So, I must ask: in a time that has a very revolutionary energy to it, what do you feel your testimony is? What is it that you have to say or that you want people to know about you and your experiences, right now.

IMB: That’s a heavy question. I’ve always felt invisible in this world. I’ve always felt ignored and invisible because of being fat, being disabled, not being smart enough, radical enough…or just enough. Society has told me that this is true. So, that’s something I’m still unlearning and I think this moment is validating the ways that Black, Trans, and nonbinary folks are ignored, diminished, and invisible—even to our own people, right? And that’s what hurts me most. We can be on the front lines. We can be organizing these massive rallys and we can be raising money. But they still forget our names. They still forget the harm and violence [done to us]. We’re still an afterthought. And it feels like such a betrayal.

I don’t know how to heal that or fix that, but this moment is revealing to me that it’s important to reach out to the people who see me as a human, as a being. They see me as a real-ass person with real-ass problems. Someone who needs to be held and supported. I’m so used to putting that support and care out into the world [rather than receiving it]. I’m also remembering how to reserve my energy. When there’s chaos you want to be there and absorb all the information, but there are also moments when we need to prioritize rest in real ways. That’s something I’m still learning to do.

I want the world to know that I exist, that I deserve joy and success and love and tenderness. I want people to know me.

TH: What do you hope that will lead to?

IMB: I hope that will lead to everyone feeling that they have a place. Not just in movement work, but in everyday community. “You belong here, you are welcome here. You are seen here. You are held here.”

There have been so many times that I’ve walked into a space and my body has tensed up. And I want people to walk into a space and feel like they can just relax. I hope I can make spaces like that. I hope I can make spaces where people can feel seen and feel held. With my work or just with me as a person.

TH: That’s beautiful. Any final thoughts you want to share?

IMB: Black Trans Lives Matter. We been here, we are here. We will forever be here. Black queer folks. I just love us so much and love everything about who we are. We create experiences. How we walk, how we talk. The cadence of our voice and the culture and communities we create. Black Trans and queer people are here to stay.

Featured Image: Film still from Sweetness, a vignette film that highlights the simple acts of love which often go overlooked. The still features a medium shot of Ireashia sitting in a chair wearing a jean romper as their grandmother moisturizes their scalp. Their gaze is looking beyond the camera. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Tempestt Hazel is a curator, writer, artist advocate, and co-founder of Sixty Inches From Center. Find more of her work at tempestthazel.com. Photo by Brian Guido.