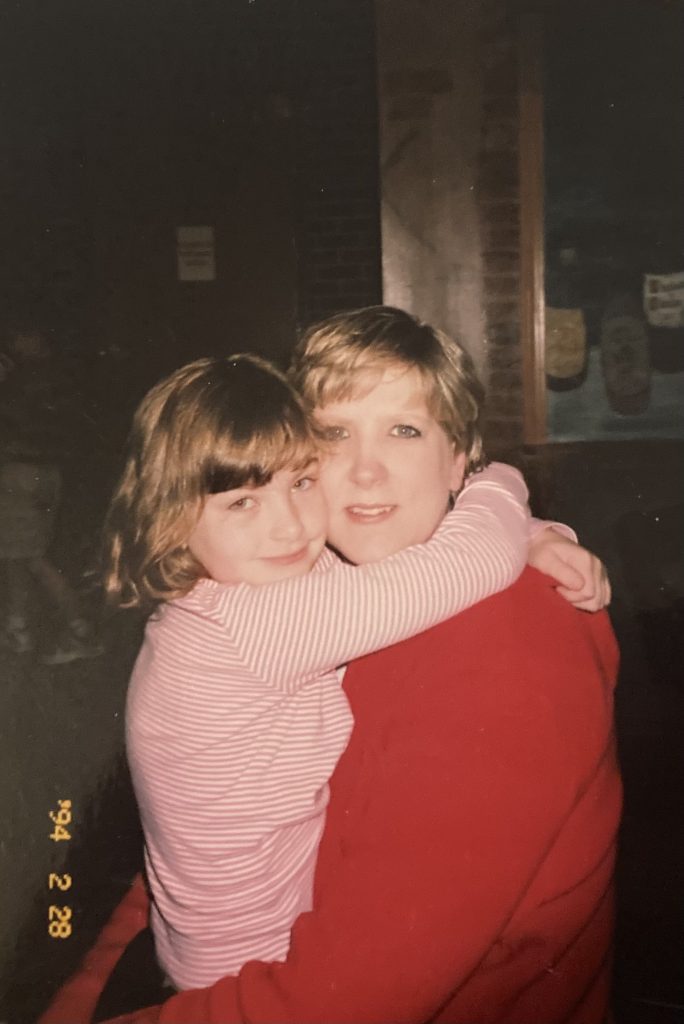

As a young mother, Gretchen felt perfection each time one of her newborns was placed on her chest for the first time. We were driving to pick up my little sister from homecoming when we discussed this, fifteen years after she last held one of her babies to her chest in the hospital. Listening to her speak, I doubted I could ever feel that way. On that drive, she told me how everything matched up when she had her children. And that, as a mother, she never felt alone. In the passenger seat next to her, I silently recalled every time she wanted to have a few minutes alone. If she felt elation at having my siblings and me as company, did it pain her to ask us for these minutes every now and again? For nearly twenty-two years, I have hoped she would fill her few spare moments focusing on her needs. For her motherhood has always taken center, so as I looked at her from the seat beside her, I hoped that during the times she hid away from us she made room for her old writing habit or the meditation I saw her do once.

Two years before my mother’s first child, the artist Anne Charlotte Robertson finished Five Year Diary, a documentation of her day-to-day life on film. Although actually spanning from 1981-1997, Robertson’s video diary made a masterclass of confessional art by showing it all, including the boring have-to moments that her audience was able to relate to. She details constant cooking all the while fixating on her weight in a direct style. She flashes clips of her trips through the park topped with spiraling ramblings, close to intrusive thoughts. A starring focus of this work, her mental illness is never edited into romanticization. Bottles of medication proved to be crucial objects throughout the film. Her work depicted the times of having to move forward in spite of the aching.

Where my mom would have to bat away kids bothering her with nonsense, Robertson was able to construct a life of creativity all her own. Robertson was born twenty years before my mother. She came of age as a creative during second-wave feminism, which allowed a push towards female creators. Somehow, though, many women got lost in the shuffle without the right encouragement or connections. Like my mother, they settled into the home with art on the side. They lost out on art school for any number of reasons, from disapproval to insecurity. They shied away from putting anything else before their home. Robertson’s passion for documenting drove her undistracted by motherhood and childrearing.

Amidst the supposed ideal of making oneself an artwork, Robertson faced her own sort of discouragement outside of a brain that sometimes wanted to shut down. Along with mental illness trying to derail her practice, she also dealt with a complex relationship with her mother. Much of her film is set in the home shared between them in Framingham, Massachusetts. In this time of fragile mental health, her mother is both needed and complicated. Robertson matter-of-factly characterizes her relationship with her mother in an interview in 1990 with Scott MacDonald. Robertson relies on her mother for transportation and mental health guidance while also fully appreciating her comforting presence as they watch movies. Family also made a sore spot in her life. She lost her three-year-old niece with the aftermath being her stay at a mental health facility. At certain points in her diary, she sighs at the thought of being unmarried. A woman so sharp in her creativity doesn’t always shun herself away to such devotion. Relationships crowd both the artists and the wives.

I make it an hour and a half into the film before I start to contemplate Robertson’s motives. In her films dating back to the 1970’s, she always pronounced her role as the star, her musings taking center stage. On my nightstand, I have piled notebooks of confessions. Some I share with a therapist, and others I idealize about putting on film for my loved ones to watch after I die. I close my screen and daydream about a career like Robertson’s. Her style of communicating reminds me of Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water. That memoir allowed me a few weeks of living my mess like the main character in a story. Aspiring to be like Robertson seemed a feasible goal for a young woman who was told that she has what it takes to be at the center. I can tape the waves that try to sink me, using the camera given to me by Gretchen.

As Robertson basked in the attention she received as the work of art herself in the late 90s, my mother held tight to baby Olivia, her firstborn. Decades ago, Mom found solace in Dare Wright’s children’s book, The Lonely Doll. I can imagine her holding Olivia and vowing that this baby would never hide away into darker material to feel seen. In the world of children’s literature animals can talk, and they give sage advice. The clumsy can still win by the end of the story, the winners can still learn.

Robertson by 2001 was worthy of a Guggenheim Fellowship. Fellows of the previous year did include a memoirist in John Russell as well as other notable filmmakers like Robertson, such as Bill Morrison and David Riker. In a sense, their male focus of living in a world wide open to them personally and artistically diverged from her films’ internal monologues as a woman. Her diaries contrasted bare honesty with opulent length, at once a sketch and a painting. Compared to a memoir or a traditional film, her hours-long work could be excessive, but the fellowship cemented her diary as an empathy device to examine a female artist in her practice, persisting.

Mom says you don’t plan another child thirteen months after the first. Like her own maternal response, I was a happy surprise too. My birth required a breathing mask, rushing, and extra days in the nursery. Held in for too long, I gave trouble to us both. On the birthing bed, Mom’s hurt fell away. Her annoyance that her husband requested a specific doctor ceased.

She was being looked after.

We think it’ll be okay.

Her numb lower half lay as just a body opposing a mind astray. Comfort has always looked different to Gretchen, barely of herself.

With one woman hospitalized, her soul floating far from her, a history of women remained behind her. The conversations surrounding Robertson tended to return to the belief that women artists are navel-gazers. Debate swirled over whether they were all vain or could somehow be lessened. Sylvia Plath crafted an identity in the confessional poetry movement. She gave the movement its definition despite the idea that the poet Robert Lowell pioneered it. Another writer, Mary Karr gave a female perspective to the 90s memoir boom. Her book The Liar’s Club made an excellent companion on the shelf to Angela’s Ashes, a work written by a male contemporary. Robertson arrived between both. Her work of over thirty hours of her pulling herself up from mental illness each day made known that women as the focus can move beyond gratuitous into a necessary understanding. Female confessional artists shape an experience.

Gretchen’s diary didn’t win fellowships, and neither did her poems. They were reserved for her daughters to feel loved after reading many years later. Olivia and I needed and needed and needed. We rolled about, cried for formula, and grabbed for pacifiers. After each cry or each grab, she must have put us down to describe us in her journal. I think of babies now as all the same. I conjured up my mother’s mind to ponder what she could write other than “Gab laughed, Liv cried”.

Robertson never had children, although she imagined the possibility often through her diary. All material came from a day in her life with creativity at the forefront. Children never ran into frame sobbing about a scrape. No child was shoved onscreen to present a worm they found in the backyard. Little Robertsons speeding through her films may have detracted from the centering of a woman stuck in her mind. In this way, Five Year Diary could be the quintessential Mako Mori Test film, with the only growth coming from the subject herself.

Mom notes how I grasp everything having to do with elephants. She must have lit up after years of wondering when her children would gain interests outside of Sesame Street. From thereafter, every elephant plush or documentary became her key purchase or viewing for the afternoon. She loved elephants before me, but I nudged her to put effort into her appreciation.

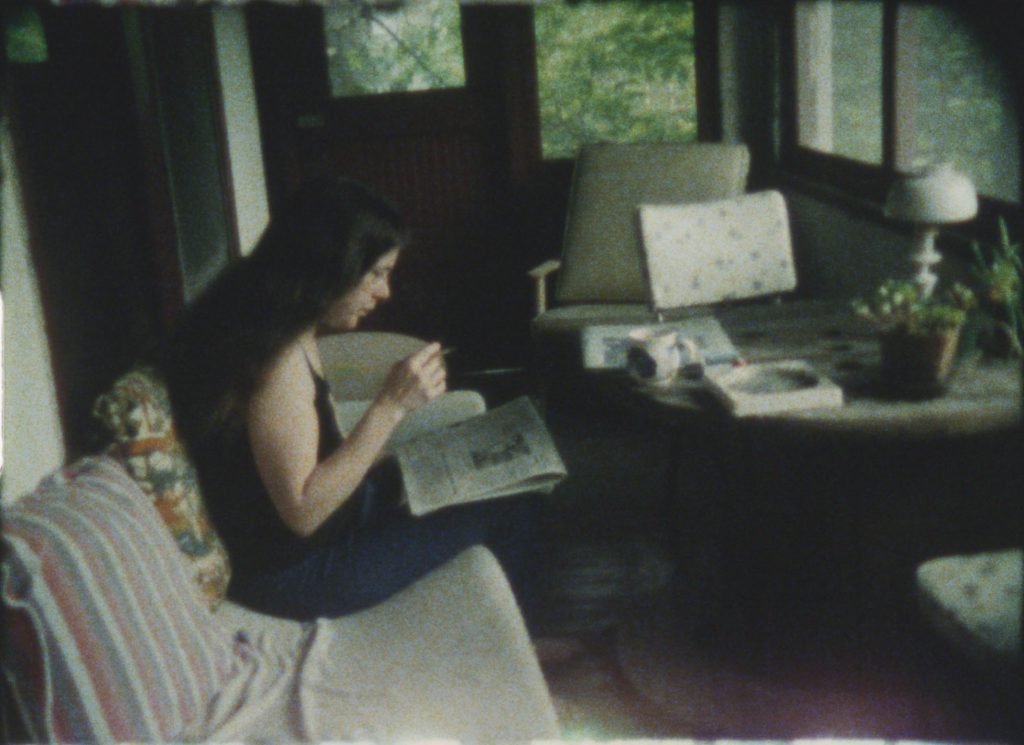

Image: Still image from Melon Patches, or Reasons to Go On Living. A young woman is seated on a couch in a small sitting room. On her lap is a newspaper that she reads intently. Courtesy of the Anne Charlotte Robertson Collection, Harvard Film Archive, Harvard University.

Despite depression pushing its way to the front of Robertson’s life, her interest in gardening took hold. Her film made in the midst of making Five Year Diary, 1994’s Melon Patches, or Reasons to Go On Living featured her delight in cultivation. It’s a more optimistic piece, Robertson relishes everything. She eats melons with those she loves and stands back to marvel at her progress. I watch this happy for her. I watch this and I’m reminded of the life my mom could have had if we didn’t come first. She recounted a painting she made years ago that turned out looking lewd without much double take.

Sometimes Mom would hand us objects like pipe cleaners, buttons, and pom-poms and tell us to make art only using those. We pasted them on printer paper to make big-headed people or pink dogs. Mom asked us for our analysis for each piece.

It’s cute

It’s funny

I like bunnies

I like purple

Ask Robertson her motivations and she’d say she was a diarist since childhood. Ask her why gardening and she might say that it soothes her or brings mindfulness. She must have sat at panels to speak on personal art giving out these answers. But none of us ever thought to ask my mom why an abstract painting on the canvas. How did you feel when your pride soured, as you realized the work looked like a penis? Her art has since become patronage for her daughters’ hobbyist paintings.

Like Robertson’s films, my mother’s notebooks could’ve advanced a more humane world. Does every young woman say that about her mother’s thoughts? Robertson made her guts and glory the stars, the depression, the creativity, the gardening, the everyday. My mom made her offspring the lead of her story for so long. Every time she tells me a story, I try to take it back to her time as a young woman in Chicago. She went to clubs, worked a solid job, and dated weirdos, all of the things young women do. She tends to accept that course in the conversation, too. She smiles and goes on to share how she had unsteady confidence then. She wanted love but could carry on with other feelings. Her children make her feel less alone. Her children annoy her and share adoration all around and spark ideas in her. I am certain she could get along with that in her own way.

Our mothers have to make their way, then they can get their fellowships. These fellowships grant a new path. Unlike throughout Robertson’s career, there is hardly any acclaim for those who chose a life of child-rearing and caregiving. Motherhood is lovely and gross. Gretchen kept diaries before kids drew on nights in fog. I consume my mother’s stories by imagining them as poems, a contrast to the chaos I think of her life with us. In vague depictions, the men from the past had no faces, just tropes. The sadness feels a little too sharp to me now. Everything she says of pain in her twenties cautions me of the tiredness to come. In the same way, I feel stagnant, my mom in her twenties feels ever-moving. Her city is no longer a haven for questioning. We drive there from the suburbs for Macy’s at Christmas. For some reason, the same baby our mothers clean up is the same one that gives them their new poetry. Her children contemplate whether this new mode was all worth it for her. Wondering whether your mother could have been the next great diarist is a purgatory that dissipates when she finally lets you read her words. Her descriptions of me are not locked away in the Harvard Film Archive. Her whole point was never to have love stored away.

About the Author: Gabrielle Lynch is a writer based in Illinois. Her work focuses on mental health, culture, and family. Oftentimes, this comes with a personal lean. She has written for 14 East Magazine and Talk Death. Her personal essay on her autism experience won a League for Innovation in the Community College award. You can find her at gabriellelynch.squarespace.com