Nearly a dozen fluorescent tubes are stacked upright in the corner of the gallery as though they are being prepared for installation or to be discarded. The bulbs glow with an uncanny, blue-green light. As I walk around the corner and pass in front of the bulbs, they go dark for a moment before re-illuminating after I continue forward. I realize this haphazard stack of fragile tubes is being externally lit by a projector. The artist Andy Graydon kept these bulbs from his former studio in Berlin (tubes manufactured in East Germany no longer fit new fixtures imported from the West after reunification) and from Minneapolis, where he collected bulbs as his studio building transitioned to LED fixtures, refashioning them as found sculptures for Free Verse (2008/2025).

Graydon’s Free Verse reminds me of Dan Flavin’s installations from the 1960s which were created with commercially available fluorescent light fixtures. Often arranged in geometric verticals or grids and architecturally situated, Flavin’s fixtures stand at attention, projecting a gaseous light out and into the gallery around it. In a 1967 essay, Mel Bochner described Flavin’s works, writing “the gaseous light . . . is indescribable except as space.” The space of the glass bulb holding the gases and the gallery space illuminated by the bulb’s eerie light. Because of the nature of the fluorescent bulbs, Flavin’s works were built to become obsolete. Flavin suggested that when the bulbs burned out, the work would go dark.

Graydon reverses this material obsolescence in Free Verse. As I gaze upon these externally-lit fluorescent tubes, I wonder, what happens to obsolescence when memory claims meaning over an object? When our memories project relevance onto an object? Talking about this trickless magic of the projected light, Graydon says, “In seeing the mechanism it reminds you how you want to see it lit up again, to come alive again.” And it’s true: Graydon’s projection rejects the uselessness of the burned out bulbs, calling forth the ghost past of these once functional objects, reminders of Graydon’s past studio spaces. Though it’s clear how it’s technically done, this immaterial projection passing into the frosted tubes is compelling—they stand silently, taking the light in, more metaphysical than scientific.

In an artist statement accompanying the exhibition, Graydon says, “In the language of acoustics, ‘early reflections’ are the first echoes of a sound that return to a listener… they give us an intuitive, often unconscious sense of the size and shape of the spaces we inhabit, as well as the position and movement of objects within them.” Richard Serra similarly described his attention to physical space in his massive steel sculptures: “Simply put, it is the difference in how you feel in a telephone booth and how you feel in a football stadium. There’s a way of controlling that difference in terms of a psychological response, which encompasses the need to reach out, touch, and experience that space.” Both artists sensitively attune their works to heighten the viewer’s conscious awareness of senses: space, light, distance, volume, sound.

I consider this attention to space as I move into a small, dark room, lit only by the ceiling mounted projector. Just as in Free Verse, discarded or defunct materials act as a site for projected light in Band Pass (altering my course) (2025). In this work, Graydon collaborated with the artist Katarina Burin on a hybrid work of sculpture and video. Burin sent Graydon over 200 pounds of detritus from her own studio for Graydon to arrange in the gallery. This pile of rubble contains hints of Burin’s studio process: wooden casting moulds, concrete, pink foam, plant roots and dry soil, and even the remains of a damaged sculpture by Burin.

Graydon projects a band of light that passes over the pile from one end to the other, never hitting the floor but only describing the physical materials’ edges as it traces the topographic rise and fall of rubble. The band of light reminds me of the running edge of embers after a hot fire or the bright bar of a scanner recording data. Graydon’s use of light illuminates and animates otherwise useless and defunct materials. This time the light is less uncanny and more investigative, even playful in a mystical or sci-fi kind of way, like a light scanner from the future or an alternate dimension, documenting the possibilities for reuse or reproduction. Occasionally the band of light disappears and gives way to the impression that the rubble is refracting light, like waves bending moonlight. But most of the time, a slow and careful viewer can align their body with the band of light so that it snaps into a single straight bar.

As I leave the dark space of Band Pass and move into the bright open main gallery, I can feel a deep rumble almost before I hear it. For Untitled (Plate Tectonics), an ongoing sound installation Graydon started in 2009, he made 11 sound recordings of the ambient room noise in visual art spaces that have been important to him: situations that illuminate the tension between what can be known through looking versus through listening. These recordings were cut to acetate ‘dubplate’ records, and for the installation’s first exhibition at PROGRAM, a space for art & architecture collaborations in Berlin, he made a 12th dubplate by recording the ambient noise of the installation itself running at PROGRAM. Since then, every showing of the work adds a record to this eccentric archive of sound that over time becomes a decaying map of its own movements through the world. Graydon describes the piece as “an auto-aggressive archive.” The acetate records grow in number with each showing, but they degrade in acoustic quality as they are played and re-recorded; the whole work is slowly becoming gray noise.

I know that I can select which records to play (alone or simultaneously) on four available turntables, but to handle and enliven them is also to weather them, hearing them in exchange for losing them. A painful bargain embedded in loss. Maybe a bit like the built-in obsolescence of Dan Flavin’s neon artwork. It’s a fraught decision, whether to play the records or not. No matter your own choice, other people will undoubtedly play the records and cause their decay. There is a palpable sense of our interdependence and fragile time-boundedness in Untitled (Plate Tectonics).

In contrast to the material degradation of the physical records, the auditory layering and built-up density of Untitled (Plate Tectonics) feels like an acoustic companion to Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theaters, a series of photographs of historic movie palaces and drive-in theaters. Sugimoto says the work began with a near-hallucinatory vision in which he imagined what would happen if he opened the shutter of a wide format camera for the duration of a film. Doing so, he captured an entire film in a single still image, gathering the density of light over time, with no single image from the film taking precedence. Graydon’s sound recordings similarly compress space into a single durational recording of sound and dislocate them from their original context; A recording of “Imageless: The Scientific Study and Experimental Treatment of an Ad Reinhardt Black Painting” at the Guggenheim plays simultaneously alongside recordings from The Museum of Chinese in America and The New Museum’s “Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st Century.” The records are like many years laid upon each other, many miles, and many memories, haunted with ambient out-of-time simultaneity.

Graydon has even connected the audio output of Untitled (Plate Tectonics) to the gallery building’s wood ceiling, walls and windows, as though this ghost sound can permeate the physical space, catching vibrations and reverberations as the gallery’s own structure–from window glass to lighting fixtures–syncopates with the bass frequencies on the records. There’s a consistent haunted quality and dislocation of senses or perception in these works. Like an invitation to a material or aesthetic synesthesia or confusion: hearing space, seeing sound.

In many works included in Graydon’s exhibition, “Early Reflections”, I feel my own consciousness mirrored and echoed back to me the more I examine and experience. Without some perceptual attention, I might walk by Free Verse without registering the projected light on the bulbs, the magic lost on me. As I spend time with Band Pass, I wait for the cyclical rhythm of the shimmering light in contrast to the broken bar of light, which I can play with and walk alongside to keep the illusion of a single line of light intact. I notice my own observation. My physical presence and sensory attention closes a loop with these works, my own experience in time rises to my attention in each passing moment. It’s a little ironic that to point to consciousness and be-ing, the formal strategy in Graydon’s work often includes re-production, distancing, or a species of phantasmagoria.

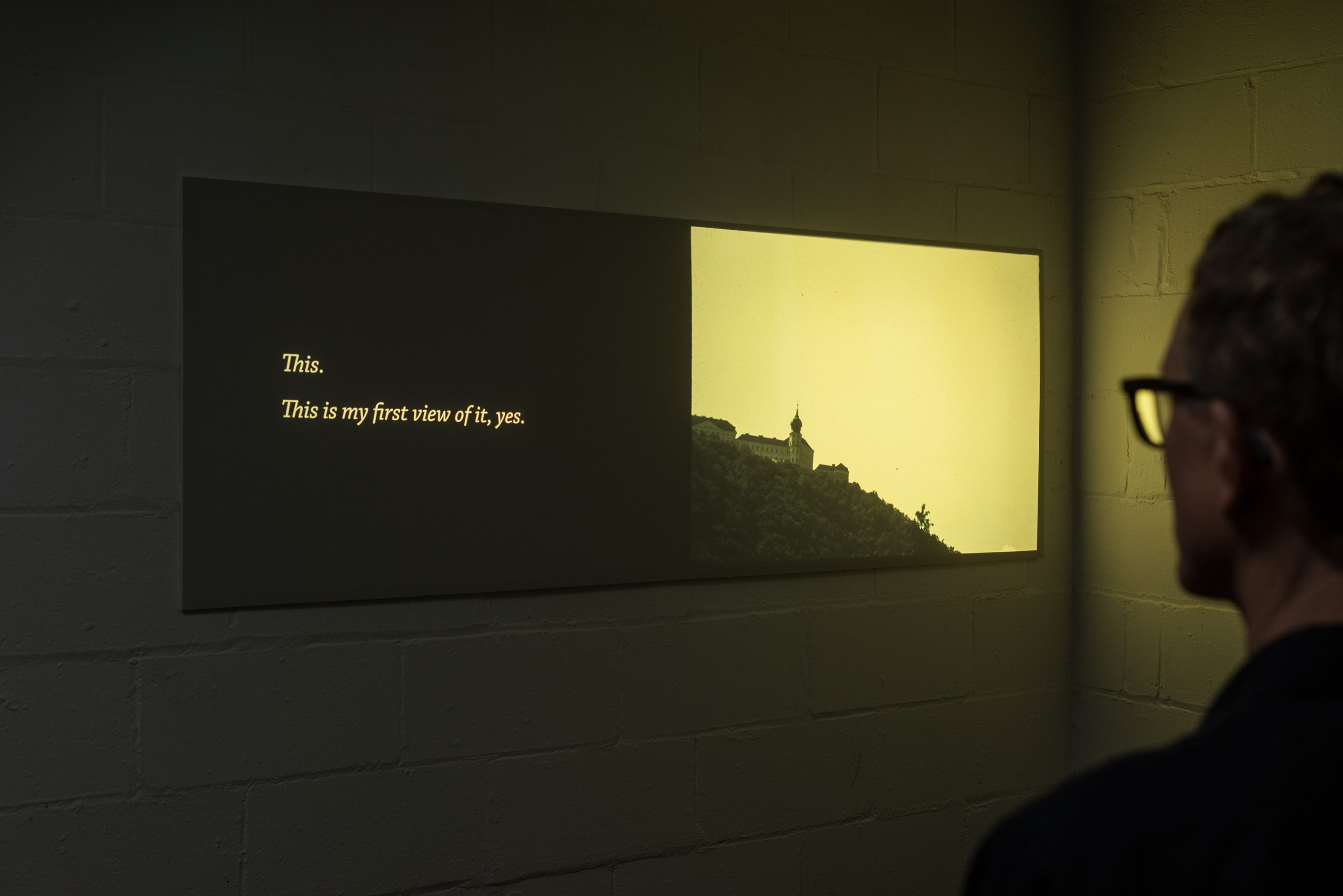

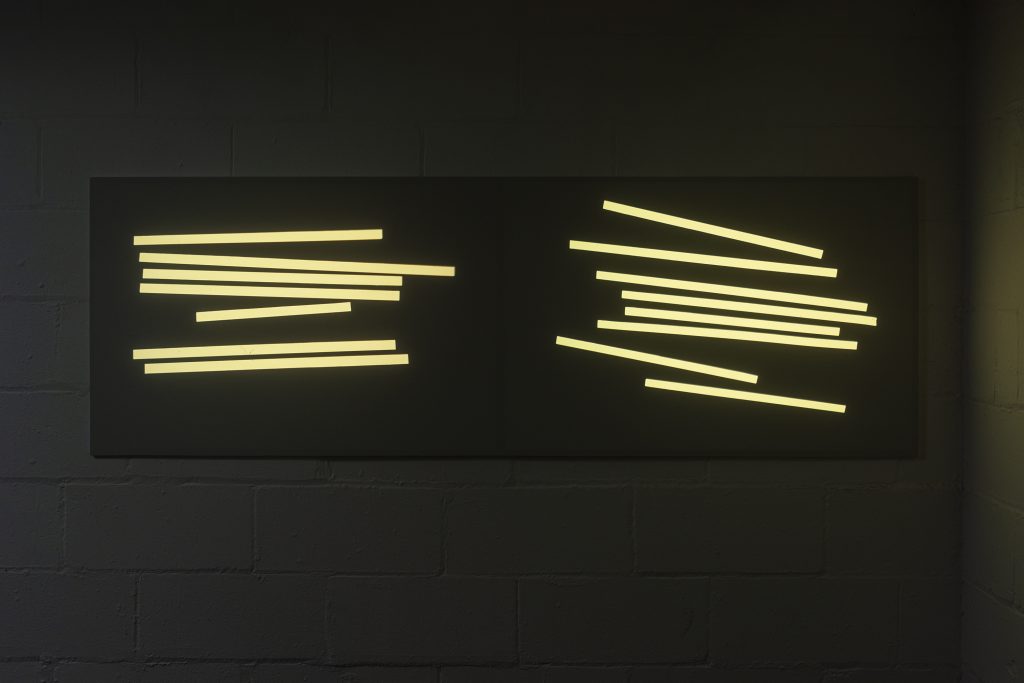

The shifting series of illusions, strange appearances, or dream-like visions described as phantasmagoria find concrete expression in A Universal Syntax (2024/2017), which includes two 35mm slide projectors programmed to run in sync. Though slides are generally outdated technology and most artists are no longer actively shooting with slide film, Graydon chose to shoot A Universal Syntax on Agfa Scala monochrome slide film, a rare black-and-white slide film that was discontinued in the early 2000s. The slides intermix images and text in the form of the transcript of a fictional interview with an ethnographer who narrates their discovery of a secret musical score composed by a monastic order which, when sung by the chorus, causes their monastery to disappear. Graydon’s choice to shoot on this particular brand of slide film (disappearing and no longer available) underscores the disappearance of the monastery and highlights this theme of obsolescence. The piece is scored only by the warm whir and click of the slide projectors as images appear and disappear in irregular succession.

Durational attention may be hard to maintain, but as the projectors perform the piece at varying speeds, a kind of visual cadence mesmerizes. I walked through the exhibit with Graydon and he described the contemporary monastery pictured as a “museum of itself” in which there are no longer any monks. Instead, it has become a tourist site and beer garden. So, what if it really did disappear? The slides click through this fictional experiment, slowly doling out the transcript of the interview in single phrases over many individual slides, interspersed with images of the monestary and its surroundings. I contemplate the myth of the secret musical score. When numerous slides with golden yellow horizontal bars appear, it’s easy to imagine them as the alluded to score itself, redacted or protected from causing further disappearances. These yellow bands recall other works in the exhibit, perhaps the bar of light in Band Pass, or the bulb projection in Free Verse. With no sound to Universal Syntax, there is no audible monks’ song to hear, but it’s easy to imagine one, as alluring, protective, or dangerous as it might be.

Throughout the show, Graydon lays out objects, images, words, and sounds with many web-like connections, like an archive to play with—the delight of wandering the library stacks and finding, with unexpected synchronicity, what you didn’t know you were looking for. These works (some made over decades, re-made, re-presented) suggest a kind of radical attention that leads to richness in spatial, cognitive, material and immaterial possibilities for being.

About the author: Amanda Hamilton is a painter and video artist from Southern CA who lives in Minneapolis, MN. She received her MFA in painting from Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA and has exhibited throughout the United States and attended numerous artist residencies including Vermont Studio Center, the James Castle House, and the Elizabeth Murray Artist Residency in upstate NY. She is committed to building community through teaching, residencies, and facilitating group gatherings of artists, writers and curators in the Twin Cities. Her work can be found at amandahamiltonart.com