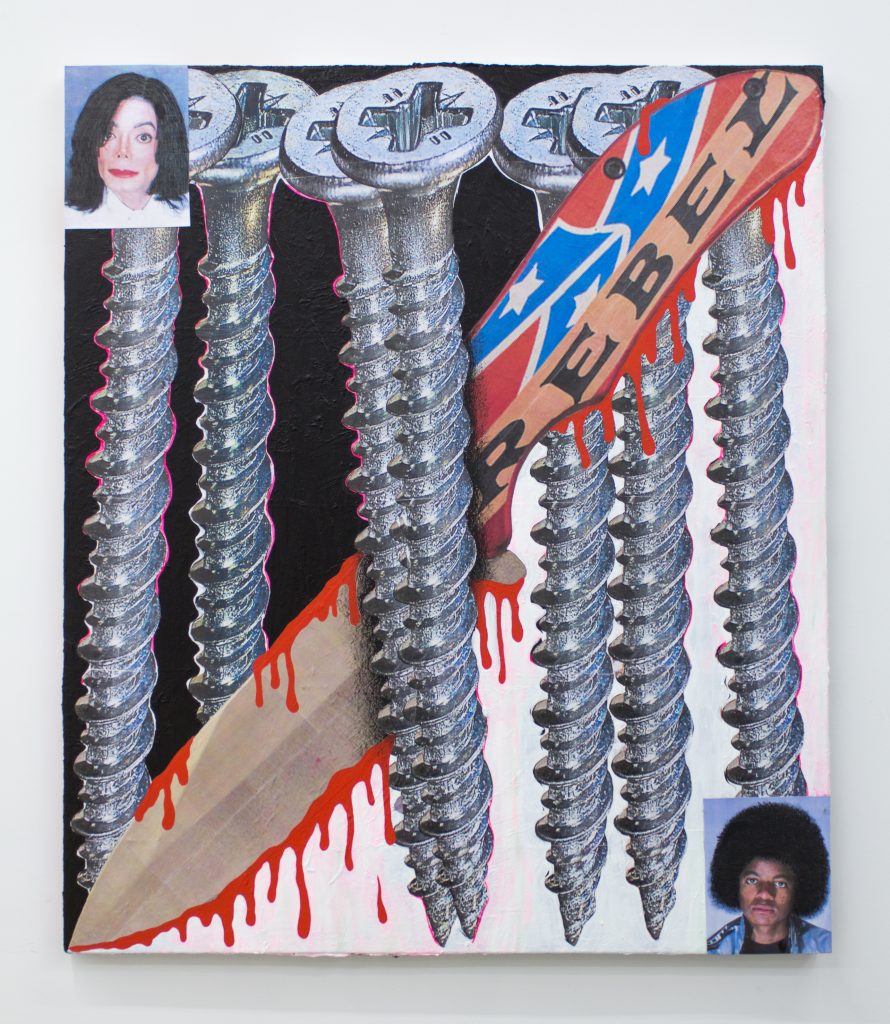

Cameron Spratley’s abrasive artworks wield mechanisms of prejudice against themselves. Famous and invented protagonists populate his canvases, enmeshed in morbid tags, raunchy ads, and biting lyrics. From Michael Jackson to Dale Earnhardt Sr., Spratley selects celebrity subjects engulfed in tragedy and controversy not to lament, but rather to evoke monocultural moments. His work compresses time like the walls of subway stations, with layered declarations of shared simulacra and common turf. Spratley tags, tattoos, sprays, stains, and fissures the surface of his work in a disruptive mark-making that renders ephemeral techniques with permanence.

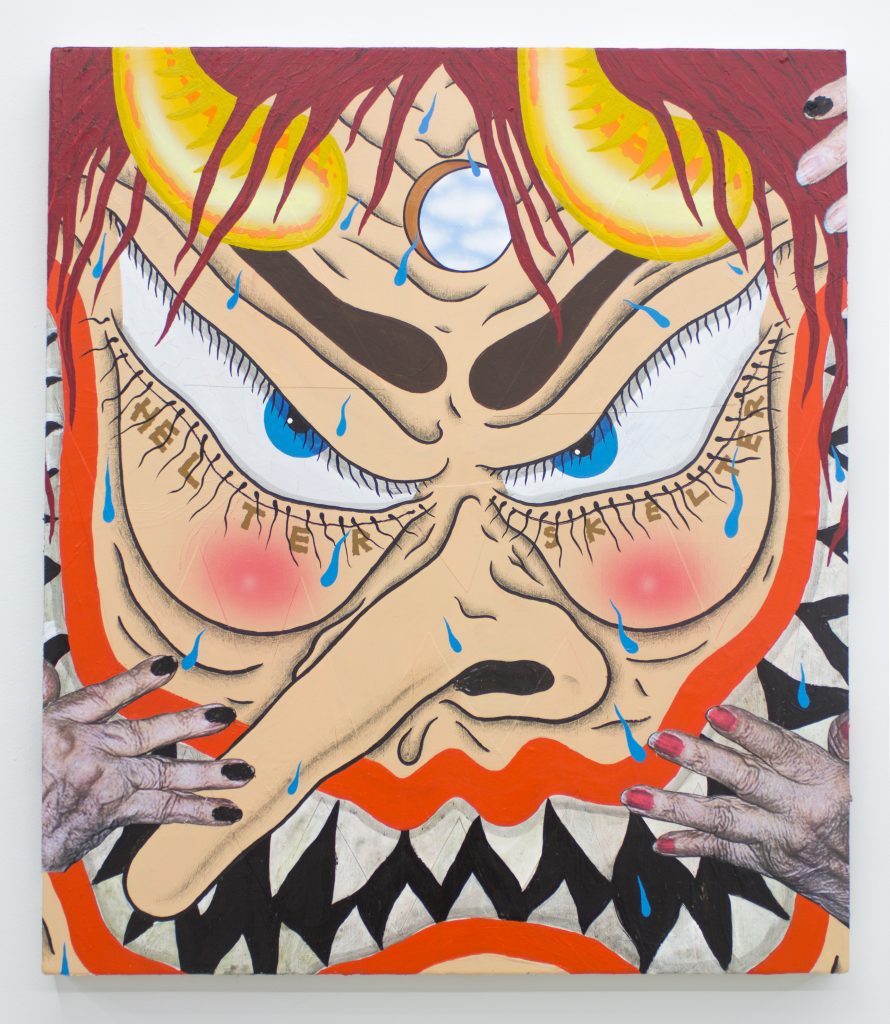

While at first they may come off as irreverent, Spratley’s artworks are effigies to the anxiety, vitality, and complexity of being young and Black in the United States. As objects, his paintings serve as vessels for distress in a moment when a nation plagued with systemic racism confronts complicity and reckons for justice. Spratley’s work is challenging. He asks viewers to untangle visuals and text, like “NO AIRBAGS / WE DIE LIKE MEN” and “LIFE SENTENCE”, a forced investment that requires deliberate deciphering and devotion. Signatures, inscriptions, painted barbed wire and chain link engage the sides of his canvases. The cartoonish faces of his Devils series are punctuated by the naturalism of two hands, reinforcing the corporeal quality of the canvas in a manner that links the process of its viewings to the building of human relations. Despite the confidence of his application of paint, Spratley’s work is steeped in vulnerability. On the occasion of his latest exhibition 730 at M. LeBlanc in Chicago, we spoke about emo rap, Chuckie, cancel culture, and self-defense.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jack Radley: Let’s talk about your show 730 up through August 29.

Cameron Spratley: I guess it’s not super common, but “730” is rap slang that I’ve picked up on for a long time—it is basically a synonym for “crazy.” I’ve always had this idea that the work speaks to the schizophrenic nature of being young and Black in America. That’s how the Devils [series] started, too. They’re based on this sense of evil that I was feeling, not following me in particular, but bubbling up in the world. Not saying I predicted anything, but I think it was a feeling a lot of people might have had at the same time. During quarantine, I was looking at all these paintings from after the Black Plague—they were filled with evil and death, themes that I am already attracted to. Each of the works is a quasi self-portrait, all from January forward.

JR: Your Devils have distinct identities—from different forehead markings to tattoos, each with a different skin hue. What goes into making a Devil painting?

CS: All of those Devils have a different starting point. There’s Blacula, which references blackface, blackness, or the Black horror movie of the same name. The reference point of the tan one, Once Upon a Time, was Chuckie, and then I started thinking about Charles Manson and Helter Skelter, which is why it says that under the eyes.

What they consistently reference most often are Japanese masks, some of which are meant to ward off evil spirits. But the figures themselves are evil spirits. They also represent African masks that are used to talk to spirits. I think they all represent a different feeling.

JR: The duality of the Devils—evil, but on your side—reinforces that there is no pure good or pure evil, something I understand throughout all of your imagery. One of the most satisfying aspects of your work is that it must be untangled; you layer text and visuals at different levels of legibility and scale to be unpacked.

CS: I used to work in a lot of art galleries and art handling. It was kind of a bummer at the end of the day because I would end up walking past abstract paintings that all looked the same. I just want to make work that I can look at forever and my friends [can] always find something different in. I use text and image interchangeably, like a rebus — like a riddle that you have to say out loud. There really is no one answer to what the paintings are about, but I like it because it tells me a lot about a person when they tell me what they think it’s about

JR: You situate your work within street culture — can you talk about this influence and what “street culture” means to you?

CS: In terms of street culture, I think about how people dress, the things they say, their music, the way people act in different communities when you’re actually there. I always think about this statistic where within the first five seconds of seeing somebody, you form a predetermined judgment of them, based on stereotypes. It obviously takes you getting to know the person to break some of those down. That was also the point in the Devils where they’re meant to be extremely scary or unsettling at first, then you start to break them down, and you feel a closer connection to them. Then you learn that they’re actually supposed to ward off bad luck.

JR: In addition to the Devils, a lot of your works are comprised of celebrities—from Michael Jackson to the Zodiac Killer to Dale Earnheardt Sr.—a lot of whom are tangled up in tragedies. How do you select a celebrity subject?

CS: My favorite thing is anything pop culture: music, fashion, whatever. My guilty pleasures are reading The Shade Room or Worldstar or scrolling through Instagram. I really hate when I have to educate somebody on a topic that they’re not familiar with, so it’s easier most of the time to use somebody like Michael Jackson or Dale Eardnardt because their story and their connection to specific cultures are almost in everyone’s mind because of how much of a household name they are. As opposed to making paintings with somebody like Tay-K, who’s a young rapper, that’s when I find a lot of pushback because people think it’s a found image of a random kid.

JR: That’s on them if they don’t get the references. But to your point, with these other figures to whom everyone has pre-existing connections, it definitely makes the paintings more universal. But these predeterminations are complex. I’m thinking of Michael Jackson, he’s Black and he’s white. He’s a music legend and a child sexual abuser, depending on how the media wants to portray him.

CS: I was really afraid when I made that painting because it’s abrasive to me, and I’m the one who made it.

JR: That abrasiveness is part of the strength of your work, but I understand how—especially in the age of cancel culture—you’d wonder if there’s any reference or subject that’s off the table.

CS: A lot of stuff is off the table. I’m not trying to be provocative just to use shock value; there’s a lot of stuff that does scare me and I have to put it off for a little bit before I use it. The hard part about working with celebrities—with the cancel culture that’s pretty recent—is that if you’re planning a show that’s four months out, it becomes out of your control if something comes up in the media. Do you want to take responsibility for what they did? I haven’t figured out how I feel about that yet.

JR: Considering the work is so provocative, it might be unexpected to read it through the lens of self-defense and self-care. I’d love to hear more about this.

CS: I’ve been thinking about these themes for a long time. Violence against the state is really just self defense. I’m obsessed with the Black Panthers and the way their movement worked—to me, I feel like the best thing you can possibly do is defend yourself with the threat of violence but never actually go through with the violence.

I like to say that the work’s not personal, but it all comes from personal places. I think about when I’m walking through a bad neighborhood on my way to the studio vs. when I’m in the Loop downtown. Sometimes I’ll wear this orange Carhartt vest, it’s a weird thing because defending yourself can also just be, like, making sure you don’t fit the description: if you wear anything specific, I feel like that’s self defense. I don’t really just mean guns or violence.

JR: You can also read code-switching through your imagery, which often holds positions on opposite ends of the spectrum of public opinion. It’s almost like these icons are enacting that twoness themselves.

CS: I think I’m getting better at that. I used to be more angry, now I’m getting closer to what I mean by a violent painting, or a painting that promotes self-defense.

JR: I know 730 taps into the influence of rap music, and you also make poetry. Your paintings read like poems; every time you look at them, you get something different out of them. You start to internalize the lyrics, the different motifs in your paintings.

CS: I’m an art history nerd, but I’m also a big hip hop nerd. The thing that I think is the most closely related thing to my paintings is this new era of rap music: emo rap. Like Lil Peep or when XXX[Tentacion] does acoustic songs, not covers, or that new RMR song Rascal that’s country rap—relating these two cultures together, because they’re actually pretty much the same. I love it because it’s all coming together but it used to just make you a weird Black kid if you were the kid who skateboarded. That Dale Earnhardt painting is my acoustic rap song.

Cameron Spratley’s solo exhibition 730 was on view at M. LeBlanc gallery in Chicago from June 13–August 29, 2020.

Featured image: Installation view of Cameron Spratley’s exhibition 730 at M. LeBlanc. The image shows a view of the gallery space at an angle, with several paintings from Spratley’s series Devils.

Jack Radley is an artist, writer, and curator. His writings have appeared in Artsy, Berlin Art Link, Boston Art Review, Cultured, Hyperallergic, Northwestern Art Review, and Temporary Art Review, among others. He is currently based in Brooklyn.