To fully grasp the dual exhibitions of What is Seen and Unseen: Mapping South Asian American Art in Chicago at the South Asia Institute, visitors must go back. I mean — literally! New York-based artist and curator of the survey, Shelly Bahl, orients the viewer to begin in the back gallery. From there, a fork in the road appears: Shadows Dance Within the Archives and Are Shadow Bodies Electric? The former exhibition traces the chronology of Desi artistic practice in Chicago to now and the latter illuminates shadows.

The exhibitions, when viewed in parallel, follow each other like shadows. On one side, the curtained, multi-generational persistence of Chicago’s South Asian art scene—in no way a secret—is shared. It challenges beliefs that even life-long locals may have held; Desi art culture wasn’t, and isn’t, only created on Devon Avenue in the West Ridge. To the contrary, it’s been everywhere and anywhere. And we see that tradition continuing today. By merging social, local, and immigration history with art history, the survey contextualizes the flourishing and critically unseen local art communities. Through ephemera, wall text, artwork, and archival video, both presentations display these communities’ enduring vitality in Chicago, which gained momentum in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Intuitively, Shadows Dance Within the Archives drew me in. The foregrounding wall panel explicated Chicago’s art history of the subcontinent starting with the 1893 Columbian Exposition—an unfortunately orientalizing introduction from the period. From there, spotlit cases of migration trends to the US with the concurrent creative pursuits tell the story of how Chicago South Asian art communities developed. Woven into those threads early on were familiar names like poet and writer Rabindranath Tagore, and polymath Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Paired with ephemera from the early 1900s, the section affirms: yes, we were, in fact, here this long ago. However, with colonialism, it’s imperative to note that most of these early artists came from privileged backgrounds, with access to stellar education within the colonial metropole.

On the other hand, Shadows Dance Within the Archives picks up and carries the historical arc into the midcentury, starting with Lala Rukh’s early work. Rukh, the Chicago-educated founder of Women’s Action Forum and Pakistani artist, was born less than a year after the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan. Her work melds the worlds between pre-and-post independent South Asia in the ‘70s. Her painting Untitled (1976) underlines how amorphous and far-reaching participating in a diaspora can truly be. She took her training from the US back to Pakistan, bringing a piece of Chicago with her. Rukh’s work alludes to intergenerational arts development following monumental shifts in domestic policy in the US. For example, The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 led to an influx of South Asians into America. Most of these immigrants, however, were working professionals who wouldn’t self-identify as “full-time” artists. Part of the motivation for this was survival. The mindset, among the parents of my generation, is “You can do this for fun, but not a job.” That doesn’t mean they don’t create for themselves . For instance, children were enrolled in kathak and tabla classes, taught to sew, and learned calligraphy from elders who moonlighted as artistic instructors. As such, they patronized the arts to the point of having a social and public foothold in the city and it reached a critical mass about 25 years after, albeit in the shadows.

The proof of these glimmers in the shadows is on the wall at South Asia Institute—flyers for Bharatanatyam performances, radio shows, and qawwalis. Notably, the show highlights Mukul Roy, who immigrated to the US in the 1970s. A former homemaker turned successful photojournalist, her moments of recognition blossomed in the 1990s.

Shadows Dance Within the Archives, further in to the exhibition, tracks trends from the 2000s to the present. The Art Institute of Chicago, SAIC, and The Chicago Cultural Center were platforms for minimalist Zarina Hashmi and sculptor Indira Freitas Johnson, whose Buddha heads pepper the city’s public spaces. Latest archival entries include the initiative born from the COVID-era Spaceshift Collective, a community of local artists, and the latest Shamiana Project which is “an immersive, multi-sensory public art installation and community gathering space in the South Asian hub of Devon Avenue.”

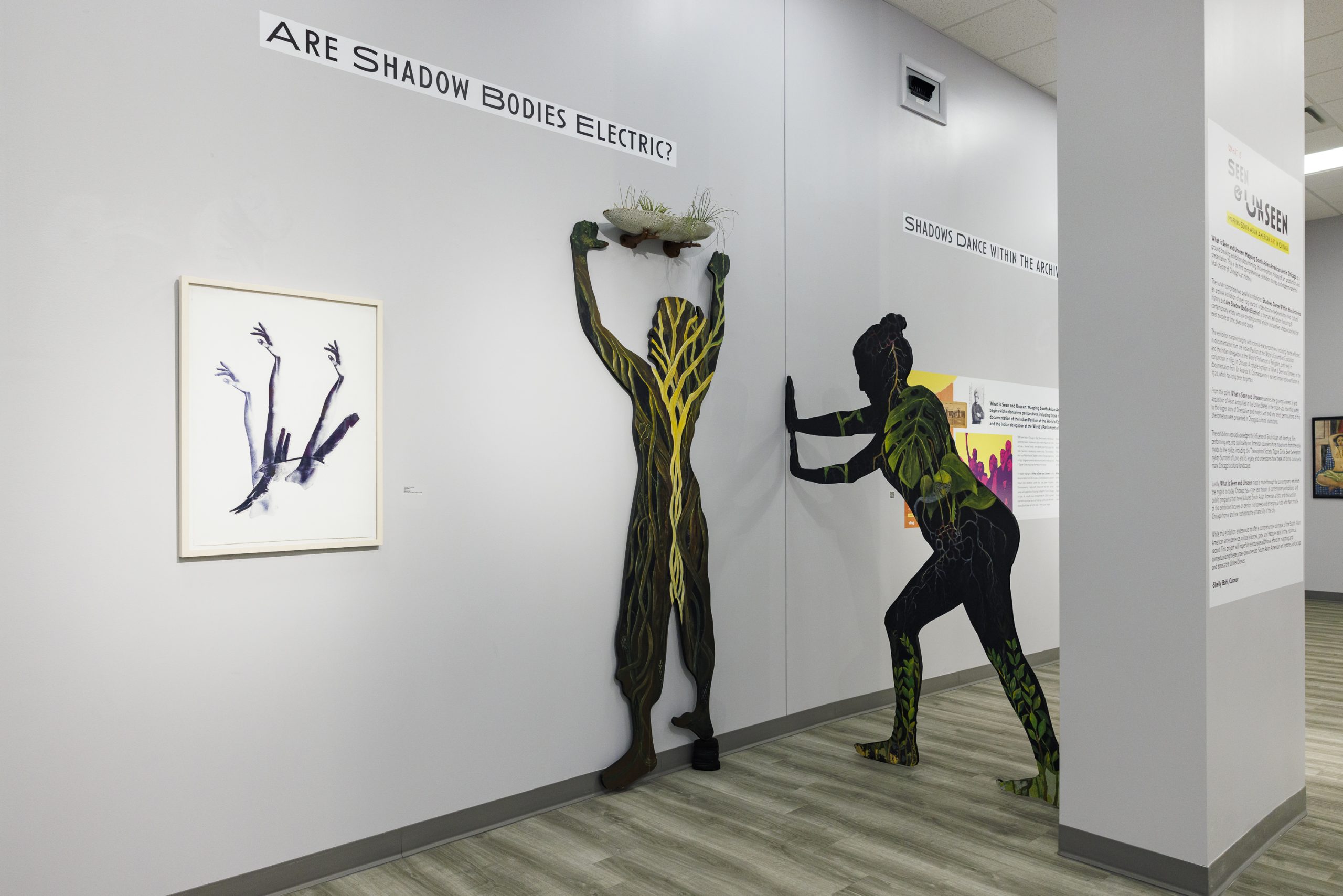

Looking through Shadows Dance Within the Archives is eye-catching to a South Asian, well-aware of this art scene, its machinations, and how deeply embedded South Asian artists have been in the city’s history. Are Shadow Bodies Electric? illuminates that dark, overlooked (by the mainstream) corner a bit more. Artists Brendan Fernandes, Tulika Ladsariya, Amay Kataria, Tara Asgar, and Sabba S. Elahi amplify how the work—and lives—of South Asian creatives persisted in the shadows.

Tulika Ladsariya’s Invisible Labor series depicts laborious femme figures. Aside from the lush verdant gardens within their silhouettes that laid down roots for survival, their identities remain anonymous. Often that silent, anonymous thriving is within subdued, day-to-day experiences. Elahi’s 2018 series, the suspect is my son, is a slice-of-life embroidered documentation of her experiences in motherhood. Distant, fish-eye perspectives capture snow angels, moments of feeding her infant, and necessary escapades for grocery shopping, making the mundane sublime through consecrated vignettes.

The role family has in fostering creative growth echoes across the exhibitions’ fork with Amay Kataria’s MomI’mSafe, a COVID-era multimedia piece that centers Kataria’s virtual body through a livestream from his Chicago-based studio. In the video, the viewer, originally intended to be Kataria’s mother during the pandemic, is regularly updated with a sign expressing “Mom, I’m safe.” Messages sent to Kataria via the livestream project are printed on thermal paper and pinned around the screen. Among the messages are “happy morning, stay happy, stay blessed, papa” and “hello amay, still working. had your dinner? love you, mom.” The project itself highlights the expression of love in parental concern, the need to be connected to our families, and how those two inform artistic practice.

Another powerful work is Asgar’s Canadian Visa Refusal which addresses immigration in the West, in many ways mirroring processes from the waves of immigration after the 1960s. Brendan Fernandes’s video work, Authority Inside, is a first-person documentation of dance within a vault that houses an archive of African masks. Through the rapid movements within the vault, the video interrogates the coloniality of museum archives, touching on the legacy that brought the Indian Pavilion to the Columbian Exposition in 1893 and the orientalism that informed it. My only wish was for Are Shadow Bodies Electric? to include more artists to allow for more parallels to be drawn. But the metaphoric mimicry of a shadow persisted.

When stepping back and gazing at the fork, it is as if the intersection whispers, “Can you see me?” But, you know, whether you see them or not, that they will continue to create.

What is Seen and Unseen: Mapping South Asian American Art In Chicago runs from May 18th, 2024 to October 27th, 2024 at the South Asia Institute, 1925 S Michigan Avenue. What is Seen and Unseen is presented as part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaborative initiative organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art. The exhibition is among more than 35 Art Design Chicago exhibitions opening throughout this year that highlight Chicago’s unique artistic heritage and creative communities.

About the author: Saadia Pervaiz is a visual artist and writer based in Chicago, IL. Her writing focuses on South Asian art and history, including diasporic South Asian art movements, nationalism, the South Asian female form, and gender.