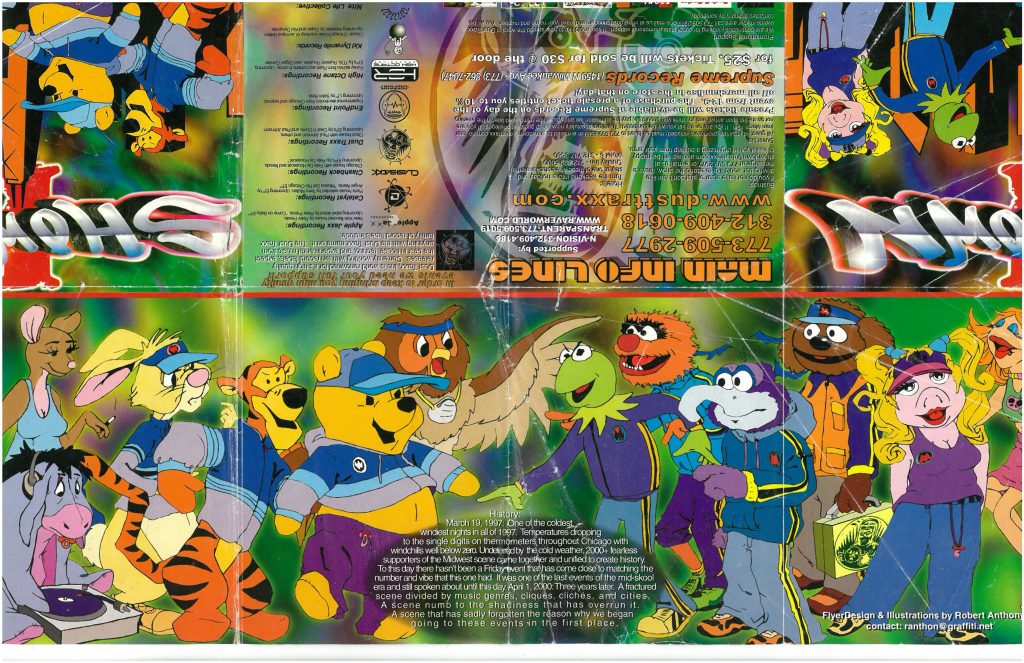

Featured Image: Front of a scanned folded rave flyer from April 1, 2000. Multicolored- mostly green Tie-dye background with various texts in different typefaces about ticket information, promotion teams, DJ line up (Steve Bicknell, Rush, Mousse T. Paul Johnson, Acetate, Dan Efex, Phil Freeart, Mark Almaria, Halo, Gant Garrard, Ed Rush, Optical, Andy C, DJ M.F. The DJs are categorized on the flyer by genres: Techno, House, and Drum n’ Bass. Midwest is a category of its own on the flyer. 2 Animation characters are pictured above each genre to suggest a duel. Animation characters such as Miss Piggy, Kermit the Frog, Winnie the Pooh, Tiger, and various members from sesame street, dressed in popular colorful rave gear from that time such a baggy cargo pants, tracksuits, baby pacifiers, and baseball caps. The colors of the clothing range from purple, various shades of blue, neon green, orange, and red. The recognizable animated characters are rendered closely to their original colors. Example: Winnie the Pooh is still yellow and Miss Piggy remains pale pink. A few of the animated characters are posed in front of an animated adaptation of the Chicago skyline with the Willis Tower is the most legible. Courtesy of Kay.

EXTENDED BREAKDOWN(s) is a series of interviews and prose unearthing niche, often undocumented histories within Chicago’s dissipating nightlife (pre-pandemic). In this iteration, Jared Brown talks to multidisciplinary artist and DJ All the Way Kay.

All the Way Kay is a multidisciplinary artist born and currently based in Chicago. They’re currently a resident DJ at Beauty Bar, Emporium, The Ace Hotel, E3 Radio, and Vocalo Radio. They hold a BFA from Columbia College Chicago. Follow Kay on Instagram and Twitter.

EXTENDED BREAKDOWNS

by Jared Brown

whispering waves tickle the back of a crown with her tongues like a summer dynast

two cavities

then

one

just rush–

Suck the colors (in),

Smell the ecstasy,

Smoke a square.

the children;

the dolls;

the selectors;

the wanderers;

the dreamers;

the girls;

the misfits;

the outkasts;

the drug dealers;

everyone blurred out

Commune under a navy (sometimes wine-colored) disguise

something for your mind + your body + your soul

everyday of your life

loops leverage a Movement

Rhythm can be the apex of divine data

Admire the stranger searching for a place they belong

Look at your reflection in the disco ball

Then, say hello to the ghosts that can only be seen there

Blow kisses to a downtempo diva

People stopped caring about their origins 3 blends ago

Ooontz oontz could never do the bass palpable justice

****

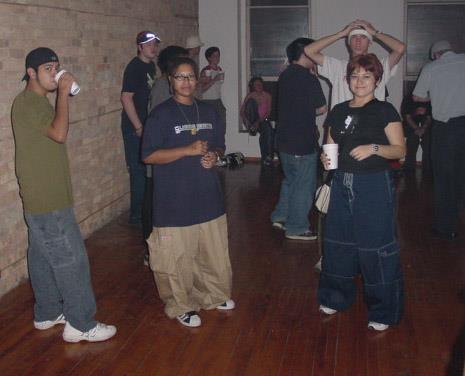

Kay: Belmont rocks was the spot for two essentially queer communities: one [was] the rave community because everybody there was just doing whatever, but also the Black gay kids would go to Belmont rocks at night.

Jared Brown: To play?

Kay: Yes, because we would all get kicked off of the block. So, everybody would walk down [to the rocks]. Have you ever been to Rainbow Beach on a Sunday night during the summertime?

JB: I have not.

Kay: All the Black gay kids had to move that way. So I haven’t really visited since they tore up the lot and then closed it down, because it has been closed for so long. I would go to Foster and hang out for a while, but you don’t see none of that anymore, especially since there are no parties like that.

JB: And when you talk about getting kicked off the strip…was it super racialized? Were white kids allowed to kick it after the club?

Kay: Well…I would say that mainly white kids didn’t necessarily congregate in the same ways. Like, a lot of the times those kids coming down this way– raves would be all in the northwest suburbs. They were really coming down here because they don’t get to see it *this* way. There were a lot of Black kids on Belmont. A lot of them were mingling with the working girls. So a lot of the times all of them would get pushed or pigeon holed–

JB: –because everyone is ki’ing outside.

Kay: Right, exactly. Shop owners didn’t give a fuck about left or right. They wanted everybody off the block.

JB: I see.

Kay: A Lot of the working girls back then didn’t have nowhere to go. This being their only friendly identified neighborhood, a lot of these girls were sleeping in gangways…I mean, same shit as now.

JB: Was there dancing at the Belmont rocks?

Kay: There was because there was always music being played and there were always tapes being passed around.

JB: What was on a tape at that point?

Kay: So, if you were lucky–if somebody did a hot set at a party that night or the weekend before–somebody had a tape of it at some point. In the same respect as when my older cousins were going to the warehouse…you were lucky if you could walk up to Frankie and ask him to dub a tape for you from that night. I had tapes from sets five, ten years older than I had ever been going to raves because people would come and be blasting music and if you asked who it was, somebody was always nice enough to give you something. Like, every time I went to a rave I’d end up with a handful of bracelets or a hoodie off someone’s back, or someone was trying to feed you or take care of you–but they would also give you music or keepsakes. I would go meet kids from the suburbs to pre-party before the party and they would always have something for you, like a Christmas card. It was a very inviting and appreciative group of people. They didn’t give a fuck about color, honestly. They were just happy to see you: “Oh you going to the party?”; “I like your outfit,”; “Who you wanna ride with?”.

JB: Can you think of a song of that time that capsules what you were just describing?

Kay: That’s definitely hard…Paul Johnson – get get down. Burned us to death…we loved it so much and we played it so damn much. I can still hear it occasionally at the club. I’m sure I could make you a whole mix of rave tracks that really inspired me to dig more. Some of my favorite DJs were disco DJs. We called it disco house–or really the DJ would play the disco at an extra 10/15 bpms. Even though it was under the guise of house, it was really just extremely sped-up disco. Or sometimes they would edit it or find fast disco. If you really dig into disco there’s some crazy fast stuff, like 135 bpm. That’s kind of fast whereas house is 125 bpm.

JB: 135 is clubby.

Kay: Hell yeah. I don’t know how we was dancing that fast either. I can’t move my feet that fast no more.

JB: You were saying you can still listen to a song now even though y’all use to play it out.

Kay: I think the memories of those times really overshadow anything…I mean, I didn’t really have any negative experiences whatsoever during that time, but the memories that I have make it so that the music doesn’t necessarily play it out. And also, it’s almost under-appreciated again? So it’s not like I can go out and expect to hear it. If someone were to pull some of those rave tracks out, it would have to be intentional.

JB: I would love for you to pull those out. You were talking about disco and bpms and it made me think about parts in disco songs like the extended version, the extended breakdown.

Kay: The 12 inch edit!

JB: The 12 inch edit!

Kay: Yes, the whole thing. You talking about the eight minute version…

JB: That breakdown moment where it’s much longer so you have a moment to connect…

Kay: …a moment to go to church almost.

JB: Yes! Where you really open up!

Kay: And it’s really where the song is to me, or where the heart of the song is. It’s not just in the chorus or the rest of the song. But it’s really that… it could be almost 30 minutes of ‘we going for it’ or could be an opportunity for maybe some less outspoken instruments to shine or just giving an opportunity for people behind you to show you what they got, too. Those usually end up being the most sampled sections of the songs, too. But it’s so awesome to see people get creative and almost in a minimalist fashion, because it’s not every piece of the song being put together. It’s just this little bit.

JB: Is there a song that emulates that for you?

Kay: loving is really my game by brainstorm. Have you seen Noah’s Arc?

JB: Yeah.

Kay: The song where they’re all dancing on stage together.

JB: In the drag show?

Kay: Yeah. That breakdown in that song.

JB: Yeah yeah yeah! I love the music in that show. I love Patrick Ian Polk.

Kay: I do, too. Is he part producer on…?

JB: P Valley?

Kay: Yes.

JB: I think so. I know he’s involved. I’m super bad with titles.

Kay: Totally.

JB: noah’s arc was important.

Kay: It was very important. I didn’t know I needed stuff like that until it was gone.

JB: When you were at raves, how important was it for you to see who was doing the sound?

Kay: I think for the most part, the DJ was always within arms reach. But you come with a certain amount of respect ahead of time to know not to bug them. I definitely grew up looking from afar. That’s probably what inspired me the most to stand there and watch them. Quite a few of the DJs that are my favorite are very soft spoken behind the tables as far as movement.

JB: They’re not super theatrical.

Kay: Right. They’re not all over the place, they’re not dancing on tables. For me personally as a DJ, one of my favorite things is discovering what your favorite DJ’s move is when they in they pocket. Like when I’m in my bag, what do I do? Like some DJs just move this one leg, some DJs clap their hands. But everybody has a very specific movement when you can tell that they’re in their groove, and it’s exciting to have a DJ invite you into the booth and you really see them get into that because, now, their energy being transferred into you.

JB: Who is someone that really left you in awe after you saw them?

Kay: Derrick Carter. Not only did Derrick Carter invite me into the booth without asking, [but also] this man is playing songs, leaving the deck, going to get me cocktails, and taking care of me in a way that gave me a new appreciation for the entire set up. Not just being invited to play and listen to music, but also…

JB: …setting the precedent for how you want to treat other people.

Kay: Exactly—being supportive of people that come to support you because there’s so much privilege with being a DJ. It’s not fair to not share that with the people that come to see you play, especially now because it takes so much to get up and leave the house.

JB: Totally.

Kay: So not only do I want to show you a good time and want you to hear good music and come dance, but I want you to know that you’re welcome here. I want you to stay. I want you to hang out with me. Because if you’re having a good time, I’m going to keep turning it up. I’ve never been disrespected or put off by a DJ, especially one that I admire.

JB: If you could dance with anyone right now, who would it be? What’s the sound? What’s the vibe?

Kay: The pandemic took a Janet Jackson concert from me and I’d really like that back. Other than that, I’ve been tapped out of that because I welcomed the break. I really love and miss DJing, but when you’ve been doing it for so long, sometimes you want to get back into other things that used to excite you. I’m interested in either tapping into what the DJs I love are doing besides DJing, or how they incorporate their other passions into that as well. So, like, DJs that make art or anything. I want to see people mix it up!

Jared Brown is an interdisciplinary artist born in Chicago. In past work, Jared broadcasted audio and text-based work through the radio (CENTRAL AIR RADIO, 88.5 FM), in live DJ sets, and on social media. They consider themselves a data thief, understanding this role from John Akomfrah’s description of the data thief as a figure that does not belong to the past or present. As a data thief, Jared Brown makes archeological digs for fragments of Black American subculture, history, and technology. Jared repurposes these fragments in audio, text, and video to investigate the relationship between history and digital, immaterial space. Jared Brown holds a BFA in video from the Maryland Institute College of Art and moved back to Chicago in 2016 in order to make and share work that directly relates to their personal history. Follow Jared Brown on Instagram or on Twitter.