I can still smell the fire on my clothes from the evening I spent at Roman Susan watching Ruby Que bend light while writing this essay. Normally, when a little sweat reignites the smoke in my clothes, the meaty and intense smell of the bonfire overwhelms me, but this lingering scent is more delicate and subtle. The sun set at precisely 4:33pm on this chilly January afternoon, although, for the audience, the sun had already disappeared behind a tall building. Que and their three improvisational partners for the evening’s performance, Ro Lundberg, Sam Scranton, and Sharon Udoh, gathered behind a small firepit on a sleek and charming three legged fire screen. The audience stood facing them and the gallery bundled up against the encroaching evening chill.

Distracted by the cold, I didn’t realize until a few minutes after the crowd had stood at attention that I was unsure if anyone was playing their instruments. Que held their flute to their lips and, while listening intently for music, I heard the rumbling crescendo of a passing airplane’s engine in unpredictable definition. I continued to strain my ears to listen for a faint note coming from one of the performers. My sonic world was completely filled with the crackling of the fire and the occasional afternoon robin call, both momentarily eclipsed by the grating sound of a motorist’s front bumper scraping a hump in the alley.

It wasn’t until the crowd clapped, queued by the performers lowering their instruments, that I understood what I just heard. I am familiar with John Cage’s 4:33.1 I have even performed it and always wondered what it would feel like as an audience member to experience the piece without prior knowledge of what was about to happen. By fortune of my obliviousness, I was able to experience the piece rather than willfully engaging in silence. Hyper attuned to my environment and slightly giddy from my novel John Cage encounter, I entered Roman Susan’s small interior.

Audience members patiently filled every available space in the gallery, sitting on the deep window sill and the ground on every side of the performers and standing on the entryway stairs like bleachers. Save for a few people in the south west corner, we avoided obscuring the largest wall in the gallery. This wall was flanked on either side by Ro Lundberg on bass and Sam Scranton sitting behind a small table of synthesizers and percussive oddities, with Sharon Udoh on Scranton’s left behind a keyboard. Que handed off their flute to Lauren Sudbrink in the audience, an impromptu addition to the ensemble. The last rays of weak sunlight vanished exponentially.

The ceiling-mounted projector illuminated the widest wall with a video of a carpeted corner below a large window meeting a white wall. I turned around and recognized the corner in the video stood behind me, a part of Roman Susan. Que had photographed the gallery for two days in August and then projected those photographs back onto the wall for the length of the exhibition, recreating the diminishing light after the sun had set and holding open hours during the night. I recognized the first images of this culminating performance as those that had comprised the night shift of the exhibition.

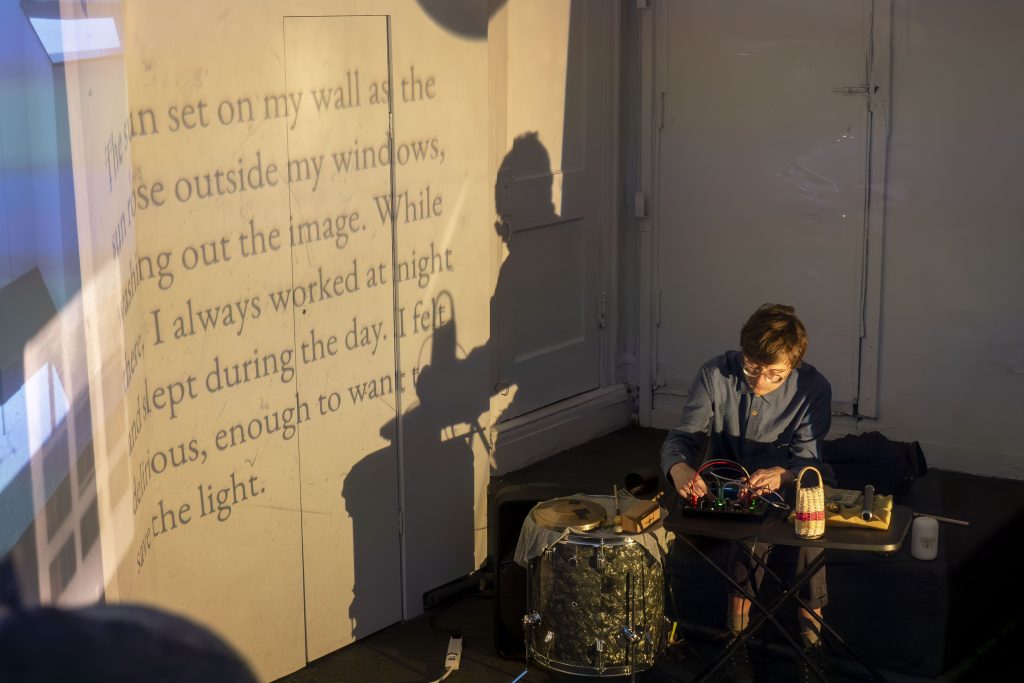

Each musician, on their own time but never out of place, together created a frantic yet pensive melody. Scranton, mallet in one hand, thumped a drum arrhythmically while adjusting his synthesizer with his other hand. Occasionally Udoh stood out with a jazzy melody that seemed to emulate from the center of a phrase. Que, crouched in the middle of the room, simultaneously managing a slide projector to their left on an AV cart and an overhead projector on the floor. With each click of the slide projector, a new image of Roman Susan’s interior gallery layered onto the wall—images of light, sharp corners, and unique shapes interacting with the architecture. My eyes worked to spatialize the slides of the gallery being projected onto the wall, to understand their relationship to the gallery itself. I didn’t want to miss anything and strained my attention to hold onto every detail.

The performers improvised steadily and gently lulling me into a hypnotic state where each image Que presented floated in and out of my awareness. The projections blended into each other overlapping and gently occluding the shadows as Que adjusted their positions. They twisted the slide projector in a slow sunset arch towards the floor and back again. On the bed of the overhead projector, they unrolled film and manipulated the light with prisms, sand timers, and their own hands, distorting the images as they projected them. I was focusing so intently that I did not notice Que standing up and starting their film projector. The zipping sound of film struggling to find its place alerted me to its presence and I turned to watch them gently guiding the film as it flicked and stuttered to life on the wall. Four scenes now overlapped and created a collage of windows, rays of light and hard edges. The sound of the film projector’s persistent fluttering lulled me into a meditative state.

Que used the overhead projector to concisely and factually recount other instances they had projected the light from a space back onto its own walls. Through the overhead projector scrawled in dry-erase marker on a piece of vellum: “The house I stayed in in upstate New York hadn’t been lived in for decades. At night, I was too anxious to sleep. The light became a lifeline. I shot two rolls of film there. They came back completely blank.”

I stewed in the images and the music, adrift in nostalgia and compassion for an anxious and sleepless Que, alone and haunted in upstate New York. More text, this time printed on vellum in a serif font, recalled their nocturnal projecting at a residency in Rockland, Maine. “The sun set on my wall as the sun rose outside my windows”. The slides simultaneously showed photos of a dark room with the shape of a paned window rendered in orange light.

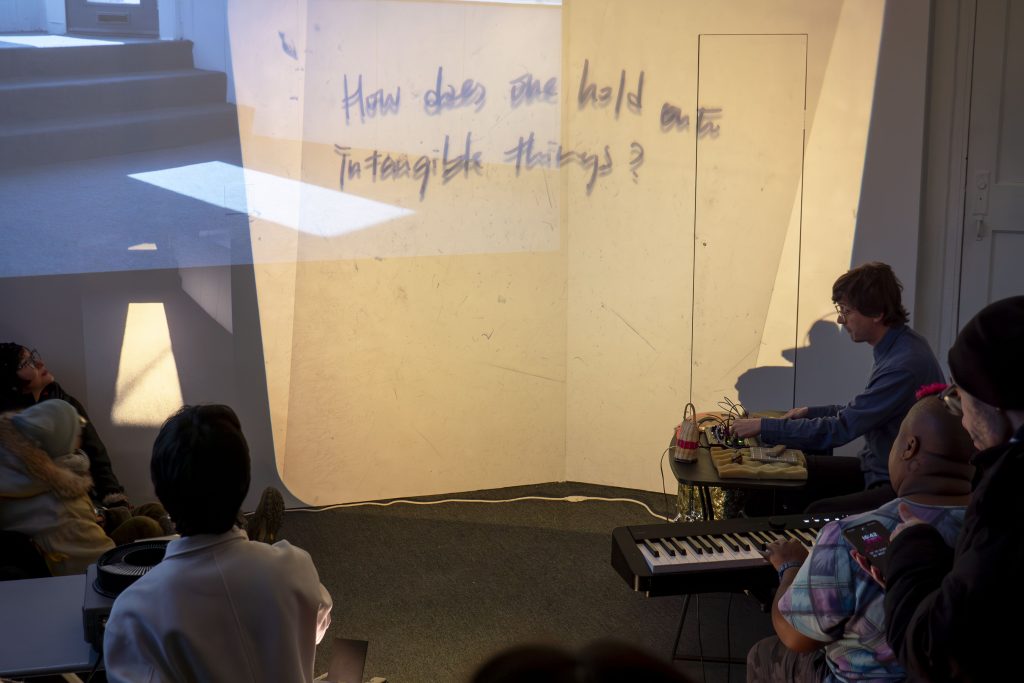

And then, abruptly: “How does one hold onto intangible things?” This question, rendered in varying opacity through the overhead, pulled me out of my trance.

Que’s desire to record the intangible evokes the feeling of sleepily closing your eyes in the morning and meditating on dreams to pretend you never woke up. Holding onto the image and playing it over and over again, a repetition to recreate a moment lost to time and perception. The setting sun, a reliable daily disappearance, often produces the same desire especially in the winter time when the day is so precious and the night so unyielding. But winter is Que’s favorite season, they rejoice in the cold, dark and fleeting weather and are not afraid of the setting sun.

In Reflections on Exile, Edward Said writes “Regard experiences as if they were about to disappear. What is it that anchors them in reality? What would you save of them? What would you give up? Only someone who has achieved independence and detachment, someone whose homeland is ‘sweet’ but whose circumstances makes it impossible to recapture that sweetness, can answer those questions.” As an immigrant and frequently travelling artist, Que is uniquely attuned to nostalgia for something you cannot hold or return to. They are attracted to the intangible, to light itself and its ability to poetically illustrate this position.

Que removed a suncatcher they had been dangling in front of the slide projector. The slides, crisp on the wall again, showed photos of hands—in the sun, casting shadows, in silhouette. Lundberg bowed rhythmically, bouncing under scattered keys as the sound of the projector blended in with Scranton’s scratching percussion. My thoughts wandered to a Tuesday in October. I was visiting Que in Bloomington, where they were temporarily living and working as a visiting artist at the Illinois State University.2 After lunch, Que took a few other artists and me to visit Eastland Mall which, like many across the country, had less foot traffic and was struggling to find retailers. Que referred to it as the “Dying Mall.”

As we wandered around the Dying Mall, they enthusiastically pointed out empty storefronts and vestiges of the sprawling building’s former patronage. We tried to make out the names of the former storefront’s ghostly signs and pondered the longevity of those that were left. One small corner of the mall was being rented out as studio space for grad students from the university. Though we were enamored with the potential of the space, we left slightly deflated, unable to escape the bleak mood it produced. What stuck with me was being able to see the edges of this world, these glimpses of what happens underneath the facade of a fabricated reality. When the psychology that is embedded in the architecture of public spaces that urges us to consume and reminds us that we are being watched breaks down the world begins to feel more uniform, more real. I felt a new level of understanding for Que’s desire to honor vestigial remnants and intangible things. When something, or someone, disappears there is not nothing, but their absence.

I returned to Que’s question—How does one hold onto intangible things? Que answers by observing, documenting, and recreating them, affording them care and adoration. By documenting the gradual, ever-changing quality of light as it illuminates a space, whether a temporary home, studio, or gallery, Que becomes a tender storyteller for the intangible.

The exhibition “Eveningnessless” was on view at Roman Susan from December 27, 2024 – January 5, 2025

Footnotes

- A modernist composition in which the performers are instructed not to play their instruments at all, often poised to do so for the duration of the performance (four minutes and thirty-three seconds as referred to in the title).

- A position which has, coincidentally, disappeared.

About the author: Zola Rollins (they/he) is an artist and writer living and working in Chicago. Their studio practice is grounded in interdisciplinary sculpture and also includes writing, bookbinding and performance. They are a founder of Switch-Hook projects, an itinerant artist-run curatorial and publishing project. He received his BFA from School of the Art Institute of Chicago in May of 2023.