Within Circles & Ciphers‘ programming, Community Peace Circle is a long established institution in both the neighborhood of Rogers Park and the city of Chicago. This space represents my earliest interaction with the organization and provided me with a foundational understanding of circle facilitation. Circles & Ciphers presently offers four types of circles on a weekly or biweekly basis to accommodate a range of different social and gender identities: Young Men’s, Women of Color, Freestyle, and Community.

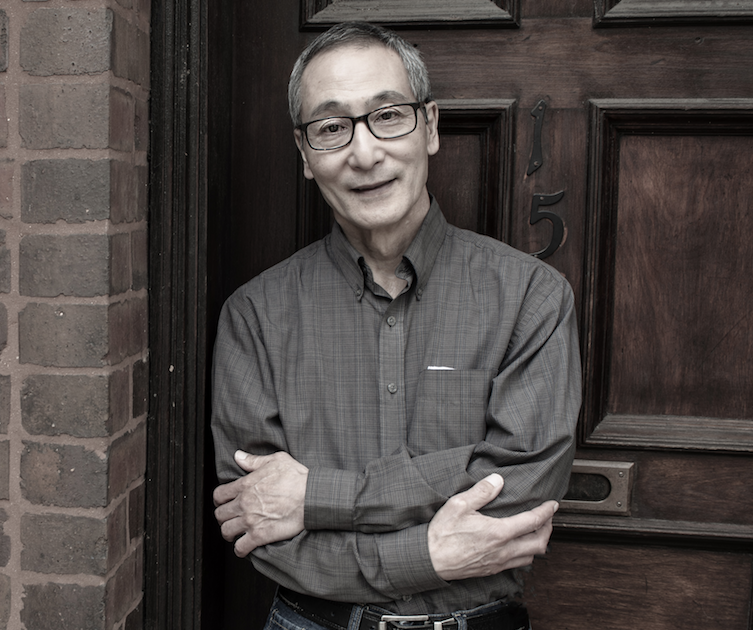

Community Peace Circle offers a flexible format which caters to the broadest range of identities and ages allowing these groups to interact and share space with one another. In order to further understand the types of people who give shape and meaning to the Community Peace Circle, I wanted to interview attendees to see what drew them into the space and what keeps them returning. This interview was conducted with Steve Serikaku, a local resident of Edgewater who is also involved with several social justice efforts that align with his Unitarian Universalist faith doctrine.

Mike Strode: How are you involved with Circles & Ciphers?

Steve Serikaku: I’m a fairly regular member and have been for at least two years. And I love this place. [laughs] I love this circle.

MS: And how did you come to be engaged with this particular circle?

SS: So I heard about it from some activist friends that live in Rogers Park. And I live one neighborhood over, in Edgewater, and I thought I’d check it out. And I was really pleased – the format, the sharing, the feeling of community is really great. There are very few places where you can get this in our society. So I really appreciate that this is here.

MS: What is it about circle facilitation that you most appreciate, if it’s particular to this circle or for circle facilitation in general?

SS: Ah! Well, this circle is led by artists, musicians. And so, you know, I think they bring a different perspective, a different way of approaching life, and I find that I have a good connection with the way things are run here. So, again, it’s not something you find just anywhere, and so it speaks to me, in a way that, even in my church, it doesn’t – I sometimes don’t find the same ways of connecting and the ways of looking at things that I find here.

MS: So the circle is rooted in this idea of restorative justice practice. What are your opinions in terms of what restorative justice practice is – how it feels, how it looks – and in what ways is it counter to the existing justice practice?

SS: Yeah. You know, restorative justice to me is a better justice system than our punitive system that we have now because it gets to the root of problems and it creates connections, and it creates community. And, to me, you can’t have real justice without having community. You know, I think a lot of people who commit what we call “crimes” do so because they have no other opportunities to get the things that they need to live in some semblance of dignity and security. If our economic system provided a way for everybody to live in dignity and security doing what we call “the right things,” I don’t think we would have prisons, I don’t think we would need police. If we had what my church head calls “the beloved community,” first of all, we wouldn’t stand for people going hungry, and homeless, and without necessary medical care. And those are things that people need, in order to live a life of dignity and security.

So, again, because we live in such an unjust society, we force people to do things that people who were not desperate, people who were not shut out of opportunities would do. And yet, because we ignore the history of this country, because our criminal justice system is rooted in what I see as protecting white supremacy and property – things that are not available to everyone in our society – it will never be just. So I’m hoping that peace circles will be a way that even people in the dominant culture can come to appreciate their common humanity with everybody else, and see that the systems that are in place now are not right. They’re not just. And need to be changed.

Now, what’s unfortunate is that you won’t get those people into this particular circle, right? Because they don’t have connections to the people who come here. You know, these folks are in the choir. Occasionally we get some people who are on the fringes of the choir, and so this is a great place for them. But you know, it also is a place for people who have been marginalized to have a connection with people who are more privileged, and so they can share their stories and help the people who haven’t been marginalized understand the real circumstances, the real oppressions in our society. But also, it provides marginalized people with a view that not everybody in the dominant culture is intentionally oppressing, and is making the effort to make the changes that are needed so that everyone can live a good life.

MS: So, you hinted a moment ago at what could be a cynical perspective – that the punitive justice system is this other water that we live in and it’s of all around us. What’s your message about how we can embody what exists in the peace circle, even if it amounts to a simple ripple that is rippling out as we’re trying to change a very weighty problem that persists all around us in society?

SS: Yeah. I think that if we can spread the use of peace circles to create community – real community – in neighborhoods, there would be less of a reason for people to call the police. Because when you have community and people act out of bounds, you can call them back in. And if you’re in relationship, they’re more likely to respond, positively. So we always want our complaining about the violence in our society, and yet we perpetuate the conditions that cause that violence. And we’re not in community, so that we can have influence to change the conditions and people’s perceptions of what is right, what is just, and so that we address the suffering that people have under our current society. You know, again, if we had the beloved community, we wouldn’t stand for people to be suffering the way that they are now. So I see peace circles as one way of developing that community.

I think it only takes a few experiences of this to get people to understand that this is the way that we should be interacting, because of the [practice of using] the talking piece, people have to listen. And in our society, [laughs] too often, people don’t listen. You know, they’re always thinking about – when somebody else is talking – they’re thinking about what they’re going to say next, right? How they’re going to rebut. But because in a peace circle you have to wait until each person has a turn, it’s not productive to be thinking about how you’re going to respond to what somebody said. Somebody else is going to say something and then you understand that when it’s your turn, you want people to listen to you, too. And how often do we get to be in a place where we feel heard. And again, that reaches us in a way that we don’t get this experience in very many places. And it helps us develop our humanity and realize our common humanity.

MS: The Envisioning Justice project is really about radically reimagining what justice looks like. And so, in your estimation, what does a more liberated, a more just, a more equitable world look like, if you had your druthers?

SS: You know, first of all, we would allow people to have a living wage, affordable housing, and healthcare and education, so that neighborhoods could be stable. You know, because you need a stable neighborhood in order to create community. And, to me, community is the foundation for a just society. Because when you get to know people and people are there for the long term, you can invest in the relationships. Whereas if people are in and out all the time – where’s the payback? If you invest time and energy into developing a relationship, and that person’s gone in a year, in six months.

If we allow people to live in dignity and security then we can have stable neighborhoods, develop community. Then, when there’s a transgression, we can have a community circle to address that transgression. And nobody has to go to prison. The community, because we know each other so well, can develop a just plan for reparations and restoring the transgressor into the community again. So it’s much better than what we have now, because right now the victim has almost no say in what the reparations are, right? We throw people away for longer and longer periods of time, but it doesn’t change the conditions that cause the person to be a transgressor in the first place. And so we’re just creating the conditions for the next person to transgress.

I think it’s much more difficult to harm somebody that you are in relationship with, a positive relationship with, than it is with a stranger. And so if we can develop a society that has stable neighborhoods so we have long-term relationships, first of all, when somebody needs something, the neighbors will help out. So that there’s less desperation for people who are struggling to survive, to get what they need for the next day, let alone the next week or year. So anyway, that’s my vision for a just society.

_

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: Steve Serikaku stands in front of a wooden door with arms folded and bearing a partial smile. He is wearing a gray button down shirt and blue jeans. Photo by Edvetté Wilson Jones.

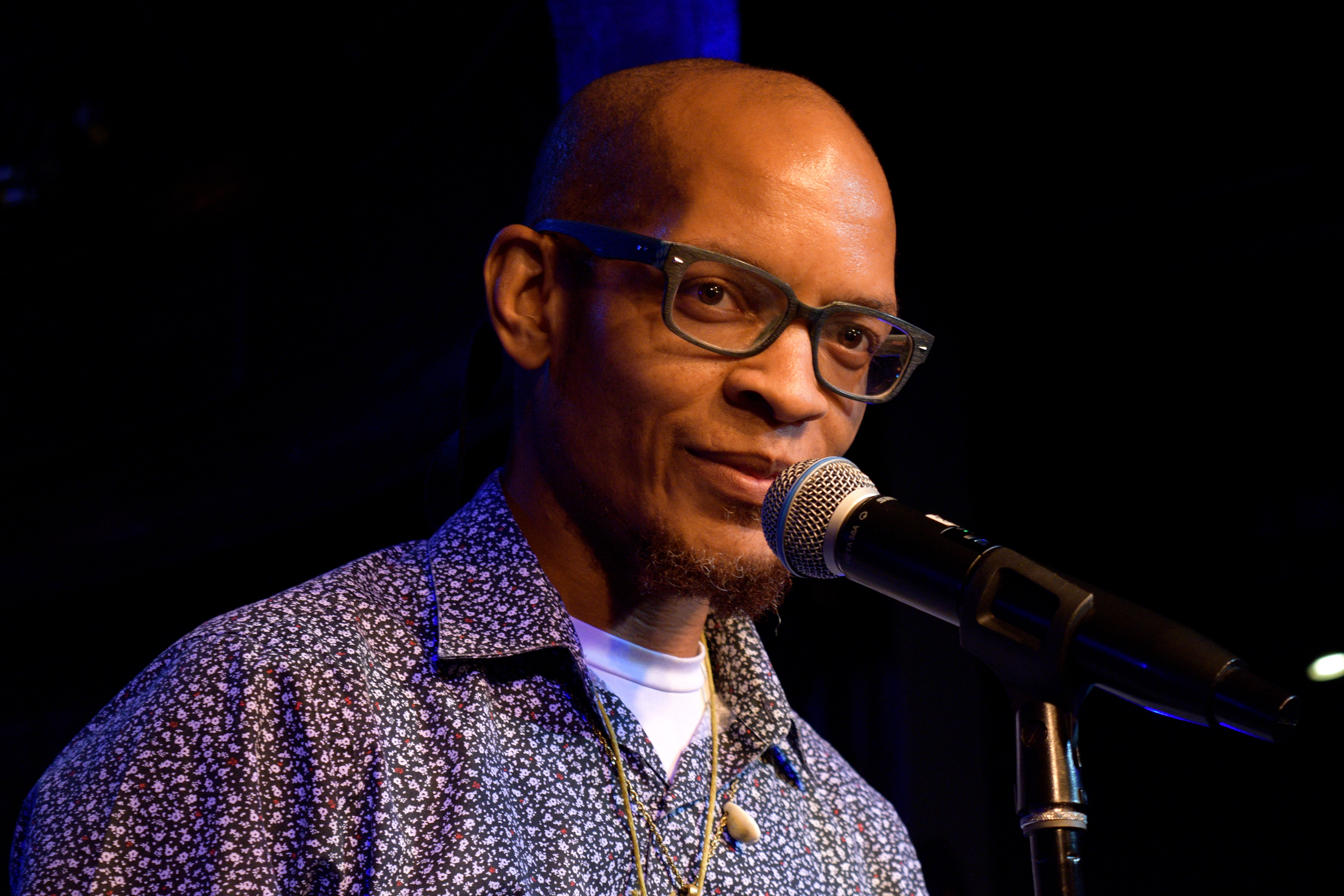

Mike Strode is a writer, cyclist, IT consultant, and collaborative social economist residing in southeast Chicago whose community engagement work has included ride leadership with the Chicago chapter of Red, Bike & Green; editorial and archival oversight for Fultonia; and co-facilitation of Art Is Bonfire. His current practice draws on all of these experiences to interrogate the intersection of timebanking, social economy and community resiliency. His grounding philosophy is mycelium, collaborative agility, empathic individualization, and all things human glue. He is founder and Exchange Coordinator of the Kola Nut Collaborative, a time-based skills and service trading platform which seeks to advance conversation on timebanking, community currency design, and social economy in Chicago. The Kola Nut Collaborative maintains a robust web presence with articles, programming, and research on myriad aspects of social economy.

Mike Strode is a writer, cyclist, IT consultant, and collaborative social economist residing in southeast Chicago whose community engagement work has included ride leadership with the Chicago chapter of Red, Bike & Green; editorial and archival oversight for Fultonia; and co-facilitation of Art Is Bonfire. His current practice draws on all of these experiences to interrogate the intersection of timebanking, social economy and community resiliency. His grounding philosophy is mycelium, collaborative agility, empathic individualization, and all things human glue. He is founder and Exchange Coordinator of the Kola Nut Collaborative, a time-based skills and service trading platform which seeks to advance conversation on timebanking, community currency design, and social economy in Chicago. The Kola Nut Collaborative maintains a robust web presence with articles, programming, and research on myriad aspects of social economy.