“It’s spooky, actually,” said P.Michael when I asked about his 37-year collaboration with fellow ONO member travis. “Sometimes, he’ll be working on something and I’ll be working on something, and we’ll show each other what we’ve been working on, and it’s the same thing, sort of. It’s like one person started it and one person finished it. It just fits perfectly.”

We were sitting at travis’s kitchen table in his South Side Chicago home on a Sunday afternoon, drinking peppermint tea ladled out of a pot. ONO is the “Avant-gospel” noise band that P.Michael and travis formed in 1980. They started regularly performing again about seven years ago in all varieties of DIY basements, art museums, music festivals, and loft galleries, with an evolving cast of band members. They have released several recordings in recent years, but the full ONO experience lives in the live show, which is tightly orchestrated, with a narrative arc and several costume changes. travis spits out words that weave history with personal pain, moving in and out of the crowd as he adds or subtracts a wedding gown, a headpiece, a tuxedo shirt, a lace veil. P.Michael helms the ship from behind a table covered by drum machines, samplers, and effects pedals. He crafts dense, groovy compositions that swell with travis’s vocal performance. I’ve never known someone not to have a strong reaction to an ONO show.

I came to P.Michael and travis with a sort of itch, a murky, half-formed question that was something like: What does ONO do to us? What is the point of ONO? I came to them wanting to know something basic and beyond reach, like where art and its power come from. A shortcut to describing what is powerful about ONO is to talk in religious terms: to speak of rapture, conjuring, elevation, possession—with travis figured as high priestess. That vocabulary isn’t far afield, given the band’s interest in religion and religious iconography.

At the center of ONO is the devoted relationship between P.Michael and travis, who met upon introduction by a mutual friend—“a wild woman” whose mother worked with travis at Northwestern University Law School.

“When I first read his poetry back in the ‘80s,” P.Michael continued, “it was amazing to read his approach to the use of language. It worked so well with my approach to the sounds that I create, because it’s musical and not musical at the same time. It’s a combination of everything that comes through my head. I constantly listen to three or four things at the same time in my house. There’s TVs going, there’s news shows, radio going. There’s classical music going, there’s jazz going, and then there’s noise going. I hear it all at the same time. So it’s a conglomeration of stuff, and his words are very similar. It’s noise. It’s like, how they say, what makes the color black? It’s all the colors.”

“I have no idea where it really started in terms of really collaborating, because I have no real interest in music as such,” added travis. His disinterest in music is repeated often, usually with a mischievous laughter. “But when I was moving through Chicago on my way to New Mexico, P.Michael had already heard the stuff I’d done in Cleveland. When I started working in Cleveland, that was right after Vietnam and Cuba, the Dominican Republic, so there was a lot on my mind, and I was thinking about what to do.”

travis served in the U.S. Navy from 1963 to 1969, an experience that provides the content for much of his writing. In particular, travis speaks about the sexual torture and denigration he suffered on account of racist treatment and accusations of sodomy. Ten years after leaving the military he found himself temporarily in Chicago, on his way to live out the rest of his life as a Kundalini Sikh, when he met P.Michael. Prior to Chicago, travis had studied performance poetry with Russell Atkins in Cleveland, OH. However, he was not interested in music. Why, then, did he eventually agree to form a band with P.Michael?

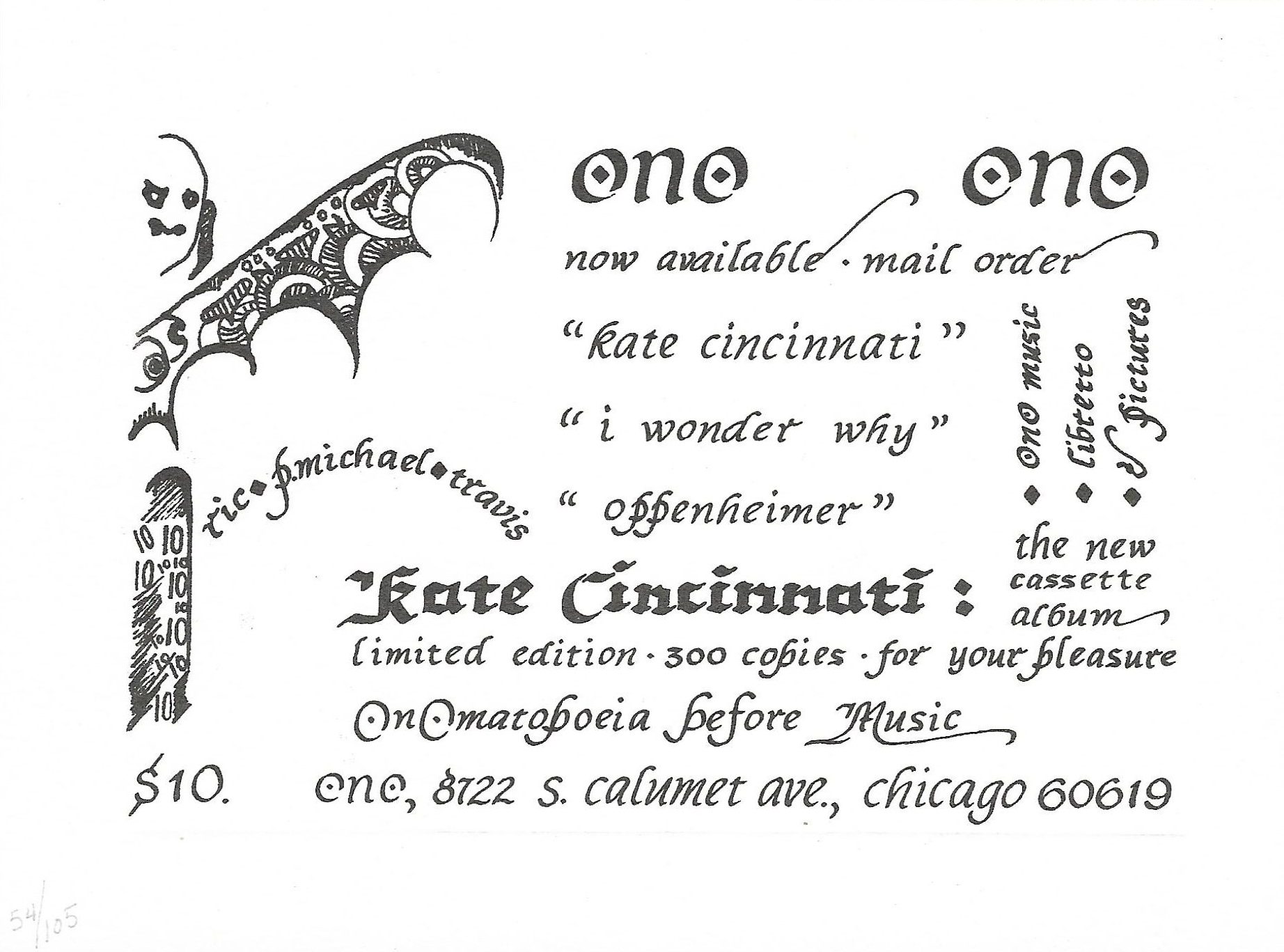

“Because he was willing to accept my idea of onomatopoeia before music,” travis explained. “Not interested in the music, but the sounds, the sonic qualities. What does it do? That’s where we connected. What’s the importance of sound that’s been organized into Eurocentric ideas of music? There’s so much else going on and Eurocentric ideas of music very often exclude Afrocentric ideas about music. And so, it seems to me, maybe noise justifies music. P.Michael actually saw that and was willing to work with it, whereas I was not willing to work with it. I knew it, but I’d given up on the very idea, the hope of even—no, I didn’t have a hope. It was just there, and I was going on to study organized religions and Kundalini and all of that, and P.Michael said, ‘We’re going to do this.’”

I mentioned an interview I had read in which travis said that P.Michael cared more about travis’s work than he did.

“Yeah, he knows my work better than I do,” travis said. “I write daily, but I’m not interested in memorizing. And P.Michael remembers all that stuff, so he writes the premise of the ONO show. Everything begins, rises—denouement—and falls—and that’s the end of it. He creates it from these words that I had forgotten even existed.

I grew up very much alone. I have sisters and there’s my mother—and wow, wow, when I tell you about her, she’s the wildest woman ever in the world. But they were there, and I never felt part of the immediate family. Growing up as the only male amongst all these women was wonderful for me because of the freedom. I knew that I did not belong in that environment, that there was a world out there I could just run to. And I would go. I was gone all the time.

Growing up in primarily black communities, especially in Mississippi, was weird because early on I had this very high soprano voice. I was abused and tormented in choir. Oh, it was just ugly. Another person would have hurt somebody. I don’t know why I didn’t, but I didn’t. Even my music teacher in the choir—and this is in Akron, Ohio now—Sandra J. Schlub, S-C-H-L-U-B, decided my voice was not masculine. And of course, traditionally, she was right. And she set about changing it. I had to sing down, down, down, always. I began to talk differently just to please the teacher, which was really bad. Then, I’m moving across the country, and P.Michael, it turns out, is able to not only allow my voice to explore itself—because, by now, there is no hint of what that voice was, my voice has absolutely been destroyed over the years and I work with that debris. So here’s this voice and P.Michael using these strange instruments, but it’s odd how he can find the voice on the instrument and then make me explore it.”

“He confounds musicians who try to figure out what key he’s singing in,” P.Michael added, “and I tell them he’s not really in one key. He’s in two keys at the same time, and they say, that’s not possible. Well I say, yes it is. He’s singing in, like, an old school gospel voice which isn’t in tune with Western instruments. So it’s sort of a D, and my bass is tuned to that and so is DaWei’s guitar. We don’t play in normal tunings because we’re playing with someone who sings in an unnatural key.”

travis is forever adamant that P.Michael is the leader of the band, that it’s P.Michael’s band and he’s just a dutiful worker. Each ONO set is unique, and every piece builds off of a premise that P.Michael writes based on a combination of travis’s words and his own research and tinkerings. The premise includes a narrative concept, such as, “Ignorance leads to destruction,” and a set of instructions for the band: “Begins with Rebecca and Jordan doing voices/Jordan with a rhythmic low doo wap layered sound (boom boom)/Rebecca with a soprano voice weaving in and out.” P Michael then directs the band via his bass or by triggering samples. And then: “travis approaches the stage…”

“I do what I do as this character,” said travis. “Once P.Michael has written the premise, he sends us it all. I then print out the words, because he always finds something that I’ve long since forgotten. So I print them all out and start thinking and putting myself in this character that is moving through this premise. That character has to have a full set of emotions that are very different than mine as travis.”

How does P.Michael know if the set has gone well?

“A feel. If it feels good to me,” P.Michael replied. “I get the vibrations more than I get the sound out of it. ‘Cause what I hear is not always what the audience hears, because I’m getting the monitors. I listen and I wait for things to come back. Then I can hear and get a feel for how things feel.”

“And the vocal character is similar in some respects in that there’s all of this sound that is happening, and this character that I’ve built is pretty much schizophrenic by that time,” travis added. “This character is being projected. People in the audience have more power over what that character is saying and doing—well, they probably know that. But the way my characters are built, they are part of that scenario. The energy is fed both ways.”

“You could feel the audience feeling it,” said P.Michael. “They say that they feel something and they’re not sure what it is.”

What does he think the audience feels?

“It’s a spirituality of some sort. It’s a meeting of a soul,” P. Michael explained. “But they feel the trauma, too. I know they feel the trauma and the drama and the tragedy. It brings out ugly things for them, that they went through.”

“All art is based in conflict,” travis added. “If there isn’t a conflict, is it really art or is it just—”

“A pretty thang,” P.Michael rejoined.

travis laughed at that. “I like that. And it’s all very nice and I can buy a pretty thang. The question then is, if it’s going to be an art performance, am I going to then allow that conflict to flower? And if not, what is it? If the flowering of conflict is real, then it’s revolutionary. It’s either revolution, or it’s a pretty thang.”

“Yeah, it’s not a rock concert,” said P.Michael. “It’s a show. We’re not doing entertainment; it’s education.”

“There’s a place for that, and that’s nice, too,” said travis. “And that can be done very artfully. Opera does that. There is room for that. In ONO maybe, over time—who knows where we are going or why, and at this point I don’t care, because I surrendered my life to it a long time ago. I have no reason to be doing this. It’s a distraction. But there was something that allowed my then self to engage in it, and I’m very happy about that. Because P.Michael has now caused to happen what I would never, never, ever, in a million years have imagined—that my work had some creative or artistic value. There was no art in Mississippi. And I was on a very different path.”

I told P.Michael that I sense that he has a knack for this, for seeing the great artistry in people. “Oh yeah,” he agreed. “I can see what people are doing even if they do not know what they’re doing. I can see what they’re feeling and bringing out of it.” Over the years, ONO has been joined by a rotating roster of band members who are often plucked from other experimental Chicago bands that intrigue P. Michael. The current performing lineup includes DaWei Wang, Rebecca Pavlatos, Ben Baker Billington, Ben Karas, Connor Tomaka, and Jordan Reyes. By now, ONO is a beloved and central part of Chicago’s music underground. I asked P.Michael what kinds of transformations he’s witnessed in their audience.

“Well, now it’s a lot more open. Back then, we were a little bit more by ourselves, because people really didn’t know what to do with us. They don’t know what to do with us now, either, but it doesn’t confound them as much. The audience is similar, although the audience was more damaged when we started. We appealed more to artists and people who were mentally challenged, damaged, or extremely addicted to drugs. We had people who would bring their drugs and shoot up.”

ONO often performs a cover of the song “Heroin” by the Velvet Underground that is as solemn and painful as it is elegant. I wondered when they first began playing it for an audience.

“We’ve been doing it since the ‘80s,” said P.Michael. “We knew so many people who were on heroin, so it means a whole lot to us to perform that piece. Which is why it takes so much out of travis to do, it always has to be at the end. He can’t function after, because of all the folks we know and all the people who were at our shows that were doing heroin. And some of them are dead now because of that, so it’s very intense. It’s a little easier for us now than it was back in the day. We had a very devoted audience, but it’s more out there now, in the world. Back then, if we opened for someone, we never stayed. We packed up right away and disappeared. We had to get back to the South Side. Get that equipment home before dark, before it got too late. Now we stay.”

“On the tour before last, P.Michael had each set close with ‘Heroin,’ even though the set before it was different each time.” travis continued, “After each show, there was a queue of kids who wanted to talk about their experience, not just with heroin but with other drugs. That made it even more difficult for me, because there’s nothing that I can offer as alternatives to what you are doing now for your condition. And folks often think I do drugs, which I don’t. I’m not identifying with the drugs, but other environments related to that drug-taking experience. . . Also, if you are ONO, what do you say to trans people? They have no idea if I’m trans or not, but there is something about the image that they see that puts on stage and shines a light on a facet of their stability. I have a lot of respect for that. As I said, I’m playing this character, but after the show, the real characters are seeing me and talking to me about flesh and blood images of themselves. So, one of the things that I like to be able to do, is talk about what it is that that person—whether it be the drugs, issues of gender, and sometimes issues of race, because black people have a hard time with ONO as well, and I don’t let that go. I jump on that issue immediately, because I want them to realize that I see you as black, and I want you to see me as black. I want you to identify with something that is black within that performance and within yourself and me. Because you are always going to be black.”

“No matter whether you think you’re a punk or not,” added P.Michael.

“And that is the first thing people see, no matter how liberal they say they are,” travis continued. “So, be prepared. Talk to me! Talk black to me! Let me know you mean it. So we get to that place right away. And it’s a difficult moment, sometimes. Because often, blacks are in that space because of their identity with the white other, not because of their identity with their black community. And here I am. I’ve been on stage and I’m challenging that. Well, no, I’m not challenging that. I’m saying, you’re still going to be black when you get back to the hood, baby. So, allow that to be part of you, more and more part of you.”

It was at this point that, thinking about travis’s queue of misfit pilgrims, I approached my murkier questions. I asked them about their idea of utopia, which took us on a long road down travis’s research on utopian projects in history, including the Oneida experiment, Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the South Side Pullman neighborhood, 19th century feminists, and socialism. Travis shared the architectural plans he had drafted for a proposed apartment complex set in downtown Chicago that would include an art education center and a roller rink. “Capitalism isn’t working,” he said. “It’s not even working for white people. Democracy as we know it is an evolving idea. Are we to suggest that it is in fact finished, and this is the crown of creation? If not, it’s time to have some fun. Come to an ONO show.”

Two nights before our interview, at a space-themed DIY show, I had the chance to follow ONO with a deejay set. As I was deciding what song to cue up first, I got the sense that I could play anything in the world and it would be received well by the crowd. ONO shakes you up so much, that’s how they leave you: in a state of willingness. Through all the pain and trauma they touch, there is always also catharsis. I suggested to travis that they evoke utopia in their performances.

“You know, that’s a weird thought,” travis responded. “Because I think what is happening is that with all the ugly stuff that is being said—when the premise is created, that ugly rises, when we get to the nasty of talking about 1919 and all the sodomy and all of that—when that denouement occurs, and when it, bam, falls, you’re left with,” he sang, “‘ohh I know I’ve been changed.’ Then you, the listener can decide what that change is. That other ugliness is still out there, but when we left you, we left you with the reality that, you know, you’re not going to die today, you got to do something about that. You gon’ be changed in ways that you never knew. That is democracy at work.

As a black person, I should be in the street now mowing down everything that is not black, shouldn’t I? There is nowhere that I’m welcome in my own country. I’m Native American. How should I be happy about anything? Anything? About my women, about my men, about my people. Where should I be happy? I have an alternative, of course, of slashing my wrist 18 times and saying, ok that’s it, I can’t do anything about this. But you can do something about that, is what we like to think. Now we have to prove that.”

Featured image: travis (left) and P.Michael pose together in travis’s home on the South Side of Chicago. travis looks directly at the camera and wears eyeglasses, a white button-down shirt, and a white cap. P.Michael looks to the right and wears a red, yellow, and green knit cap and rainbow wrap-around glasses. Behind them, the wall is covered by travis’s painting, including a painting of a white face surrounded by red flowers that is the cover of the ONO album “Albino” (Moniker Records, 2012).

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.

Starting from the proposition that art-making is world-making, Sasha Tycko combines community organizing and curatorial work with writing, music, and performance. Tycko is a founding editor of The Sick Muse zine and an administrator of the F12 Network, a DIY collective that addresses sexual violence in arts communities. Find more on IG: @t_cko and at www.nomoneynoborders.com. Photo by Julia Dratel.