I visited the Days Later, Down River on a deceptively cold spring afternoon—the type of Chicago day where the sky is clear and a chill seems sharpened by the sun. I hurried to the gallery and pulled its front door to run from the wind on my back; as soon as I stepped in, the air behind me vanished as my eyes found Maia Cruz Palileo’s light installation. Bathed in this glow I found my body adjusting to a new warmth.

Light filters through the leaves and shadows grow long—the walls of the Monique Meloche Gallery are illuminated with the pearlescent gleam of a forest’s foliage as if a late afternoon sun has sunk into dusk. Entering Cruz Palileos’ solo exhibition, Days Later, Down River, one is immediately struck by an overwhelming calm met with wonder—I am now lost.

“And when she broke open our darkness. It was day. We saw each leaf and tree was filled with light” – Shirley Ancheta, Long Kwento

In the center of the first gallery room lies a banig, a traditional handwoven sleeping mat of the Philippines that has been brought out of a sterile archive to serve its original purpose as a place to restore and gather. It was laid flat on an elevated platform with only a few imprinted creases indicating its century-old age. I think of the many nights it had served as a cool refuge on the hot earth for someone to lay and how, now, in this gallery, it has finally found light once more. My eyes gently rest on the banig, and I feel at peace and in communion with this object—as if, true to its destined use, I were encouraged to gather myself before my journey could begin.

It is through this initial, intimate invitation into another realm that Cruz Palileo begins a winding exploration into the depths of their personal archive, ancestral mythology, and Philippines lore. In their newest collection of panoramic paintings, each is a glowing gem that is as much visual mosaics as it is a narrative collage. In a self-assured step into a tumultuous composition, Cruz Palileo proposes a seminal embrace of the multiplicity that defines Philippine history and identity.

My last visit to the Philippines was only a few short months prior. The trip marked an emotional return for myself and my immediate family whose entry to our homeland had been quickly cut by the restrictions of the pandemic years. In the early 1990’s my mother and father graduated from the University of the Philippines and, as did Cruz Palileo’s parents, immigrated to the United States. Since then, we have made an annual return that is a yearly, unfurling sigh of relief—the first steps off the plane are my first moments enveloped in the distantly familiar colors and chaos of Manila. I could lose myself in the crowd as, finally, one face amongst many whose dark eyes mirrored mine. I am ready to be lost.

My memories of this last return echoed behind my footsteps as I entered the gallery’s second room and was welcomed on my left by a row of five small framed gouache paintings. To my right hung four of Cruz Palileo’s panoramic paintings framed by three walls. I lingered at Veiled Dancer (2022), the first gouache to greet me. A woman in a billowing blue filipiñana stands with her hip cocked and her confidently perched on her waist. A flower crown on her head holds tight a white gauze that drifts over her face. Obscured, her eyes appear as two blazing white stars. She feels somehow familiar. Have we met before? Her expression is just beyond sight, and yet, there is a growing sense that I am no longer alone.

“After all, we like our ghosts, hunger to be seen. In the leaves, in the birds, in the window sills, and on the boats, laughing and dancing, eyes beaming, through the kisses and the embrace”

– Kim Ngyuen, Long Kwento

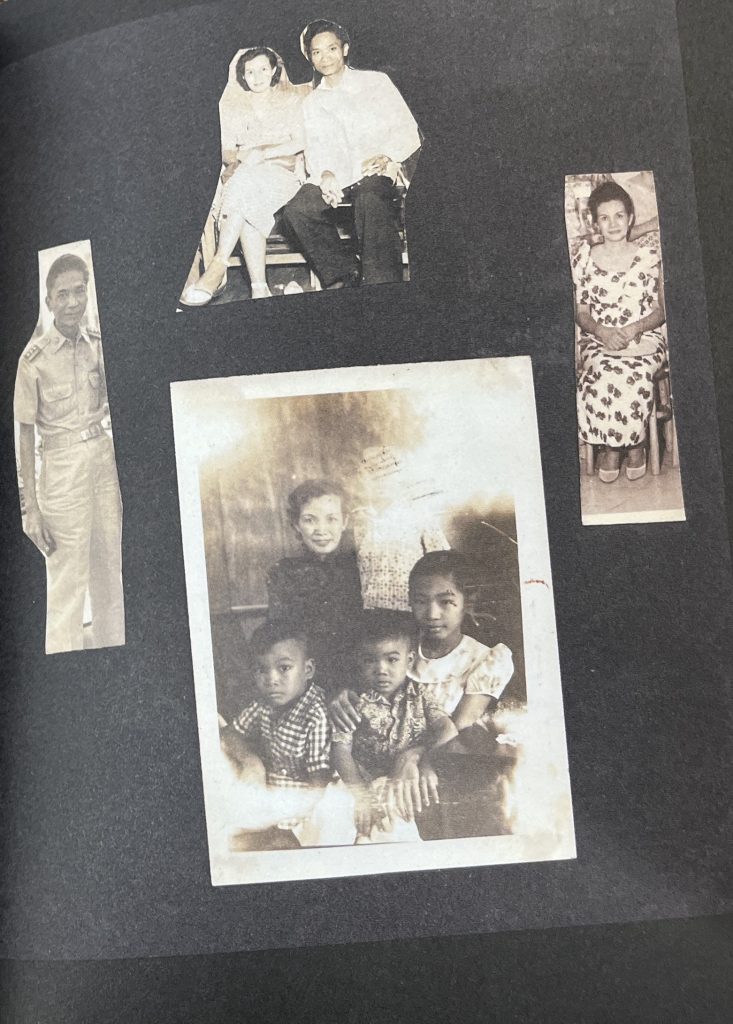

Cruz Palileo’s figuration is born from a process of collage. While researching at the University of Michigan, they came across the photographic archive of Frank C. Gates, a professor of botany at the University of the Philippines (1912-1915). This archive contained documentation from excursions into Mount Makiling and Mount Banahaw, two dormant volcanoes surrounded by a deep tradition of lore. These mountains are believed to be stewarded by diwatas (goddesses or spirits of the forest) who, in some stories, gleefully trick travelers into losing their way by creating a long and confounding path. This mythology is in direct conversation with Cruz Palileo’s process of mining their own family history to discover bits and pieces to incorporate into their paintings—a seemingly unavigable path made only more difficult by the Philippines’ history in its entirety.

Disrupted by colonization and occupation, the country has a disparate lineage whose fracture is magnified amongst its diaspora. Spanish, American, East, and South Asian influences have an arduous history of integrating themselves into the nation’s cultural lifeblood. Binary categories melt in the Philippines and amongst Filipinos who have grown to understand these complicated roots as their own rich, complex origins. For this reason, notions of linearity have no place in Filipino culture. Moreover, adhering to upholding a clear chronological timeline connotes the existence of a beginning and end—a break in linearity signaling history’s ultimate extinction. Standing in the middle of the room I begin to understand how each luminescent patchwork image is a refutation of this extinction and a movement towards a multiplicity that embraces the truth of a complicated path. Cruz Palileo’s works are of dizzying depth, and intentionally so. Their use of transparent leaves underneath opaque vines creates landscapes that are as difficult to visually decipher as they would be to physically traverse—as if we ourselves are challenged to find our own way. Each painting invites a second, third, fourth, or fifth look, rejecting any form of flattening and instead proposing infinity. In this way, Cruz Palileo’s works are the antithesis of an “end”—I feel emboldened by each edge and turn, to trust my gaze as a path guiding me to encounter a new beginning.

However, Cruz Palileo does not propose that this path be undertaken alone. I finally make my way to the third gallery room and meet The Slow Course of Water (2023), a cacophony of colors that exemplifies the painted worlds I had grown familiar with as Cruz Palileo’s distinct style. In this shimmering waterfall scene, lit candles line the grotto’s rocky edges as if someone mid-prayer has hurried just out of sight. A woman’s figure is painted in the top left corner with her back turned to us as her body meets the edge of the waterfall. Golden water fills her figure as purple leaves lay across the edges of her hair. Liana vines wrap around her torso and sprout into her chest. Upon closer look, I realize she is not there at all, but rather a part of the forest itself.

“What does it feel like, look like, to mourn for, to attend to, to yearn, to long, to need, to split the tides and drown under their weight, to be helped by death and to live with its specter?”

– Kim Ngyuen, Long Kwento

I walk back again to their other paintings and gradually notice that more hidden bodies begin to appear. The forest is alive with these phantoms of figures whose outlines, as I previously discovered, are inspired by both archival photographs and their family members themselves. It is through this blurring of presence and absence that Cruz Palileo invites the past and present into one frame. They offer the idea that omission is not a lack, but rather an opportunity to walk alongside someone who is just out of reach—ghosts, ancestors, and spirits alike.

As I leave the gallery and walk past Cruz Palileo’s paintings one last time, I am compelled to linger. I am suddenly reminded more than ever of my last return to the Philippines. A memory arises of one particular afternoon my family and I took a trip to a beach in Bagac, Bataan. There, the sand was black and the waves grew calm in its cove. I remember slipping into the warm water just as the wind picked up and bobbing with the tide as my feet left the ocean floor. I allowed myself to float. As I swam along further, I could see better that the shore around me was becoming a jungle with impenetrable depth. My chest at first tightened, but then relaxed, as I am enveloped for the first time in the overwhelming sense that I am exactly where I am meant to be—as this feeling washes over me, I close my eyes and imagine gently drifting further and further away, until I am no longer in sight.

Days Later, Down River by Maia Cruz Palileo is on view at Monique Meloche Gallery from April 1 through May 26, 2023.

About the author: Francine Almeda (she/her) is a Chicago-based, Filipina-American independent curator, writer, arts administrator, and gallerist. She is the founder and director of Jude Gallery and the Manager of Heaven Gallery. Jude Gallery is a project and exhibition space based in Pilsen, that supports Chicago’s contemporary, and BIPOC/queer/trans artists, with a particular focus on experimental art formats and community-centered programming. Her work as a curator and organizer nurtures new methods for collaboration and participation while exploring methods of art as a care-taking tool. Through her exhibitions and events, she aims to create space to uplift other BIPOC and Southeast Asian Arts workers.