I first met Jeffrey Michael Austin through an exhibition we were a part of at the Chicago Artist Coalition in 2015, during which he was a resident in their HATCH program. He then had successive projects in the St. Louis vicinity where I was living, and I maintained an ongoing admiration for the cleverness, humor, and versatility of his practice (he is also an accomplished musician, one-third of the trio Growing Concerns). He is an artist that is responsive to his environment, locating the wonders of natural elements, as well as wonder-ing about the state of human nature. His re-staging of common objects and occurrences straddle the playful and the political. As the latter becomes more and more urgent, he engages in critique that arises out of a call for empathy. Over a very long email correspondence, we reflected on some recent bodies of work, as he prepared to open his solo exhibition ‘Outstanding Balance’ at Heaven Gallery.

Lyndon Barrois Jr: It is notable that there are a lot of stars in the recent work, and stars for me always relate to the movement of time and distance. With the floor works, the components involved settled my mind on the phrase scrubbing time (that function of manipulating audio or video on smartphones), which does the interesting work of bringing different temporal moments together: the mop bucket (and cleaning for that matter), and of course the stars, aren’t quite marked by digital technology, but the joining of their contexts through language bring them to this moment. I suppose that’s the excitement in making—not just a surrealist juxtaposition, but in regards to time, it’s like a haptic montage. Do notions of time have any part of your thinking about these works?

Jeffrey Michael Austin: There are so many different perspectives and twists on time that come into play throughout this whole body of work. With the floor works, it was all about bringing together distant points on this vast spectrum of time and space; joining the gesture of routine cleaning—a task that is small, both in its relative [in]significance in time, and in its banal humanness—with a view of the cosmos: endlessly vast in its ancientness, omnipresence and inexplicability. I find a real joy and profundity in collapsing these micro- and macro- views into singular objects or situations because they immediately take on a sort of absurd embodiment of the human condition itself—our conflicting perceptions always running parallel through our lives (half-aware of the untouchable mystery of our being-at-all, half-absorbed in the seriousness with which we take the concerns of day-to-day life).

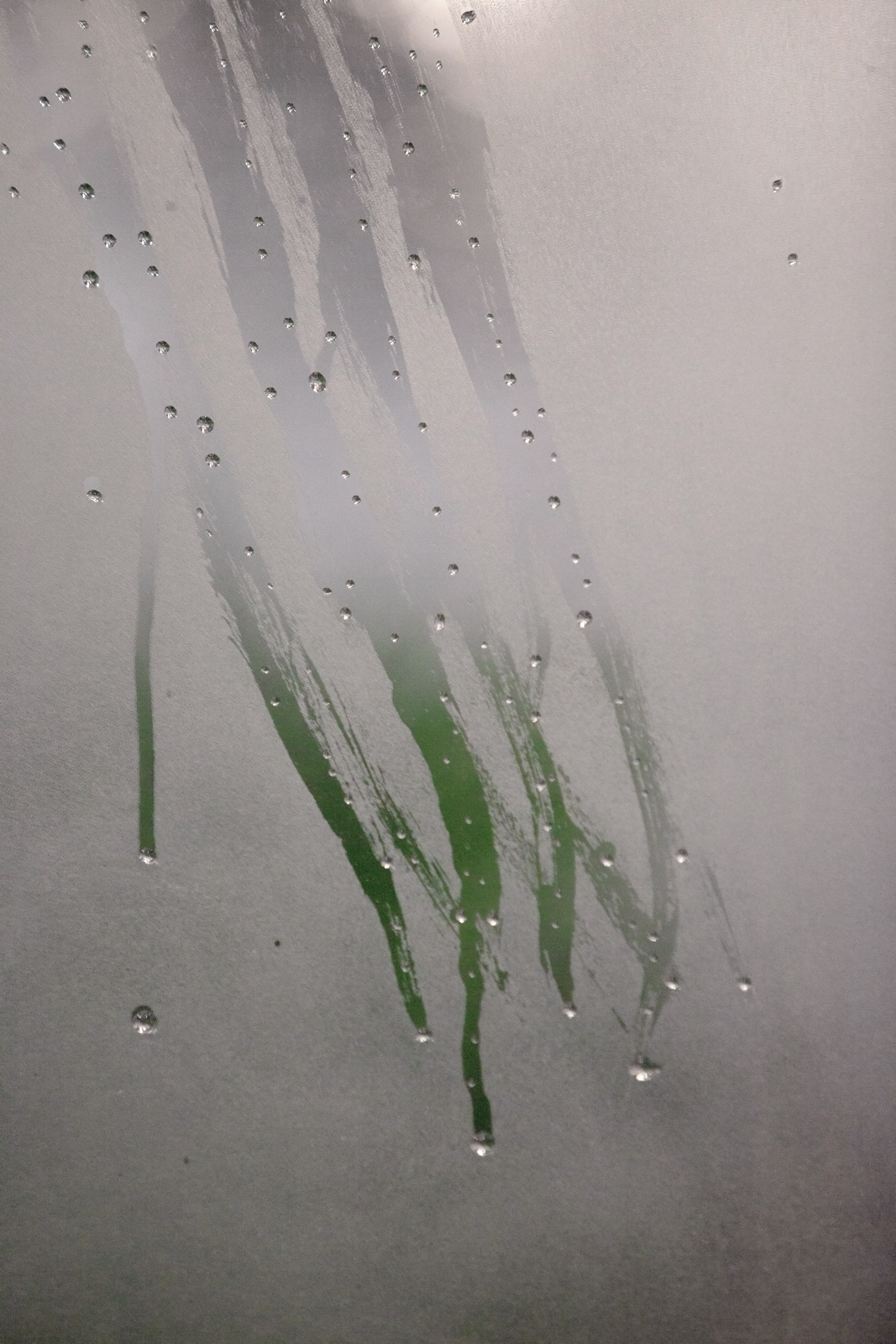

There’s also a clear play with time taking place in the mirror works—a freezing of time and a challenging of the familiar. These works are rooted in the overarching desire that fuels most all of my work: to set up a relationship between the work and its visitor that leads them to question their own faith in the faculties they possess for understanding the conditions of their living environment. In simpler terms: a means through which to constantly be encouraging the question, “Do I truly have a grasp on what’s going on here?”, where the work becomes less about the object on the wall and more about the visceral questions and curiosities that suddenly fill the air once the relationship is made. “What are the elemental conditions of my environment? What am I feeling or experiencing? Do these align?” As it pertains to any of my work: if a person walks away from a piece with an even slightly higher degree of openness or sensitivity to the magic and malleability of the world around them, I consider it successful. For this reason, it’s becoming increasingly crucial to me—most clearly in the mirror works—that my artworks resemble subtle and ubiquitous objects or situations more so than institutional art objects.

LB: I want to linger on this idea of conventional/institutional art objects for a moment, because it’s quite clear that objects are important to you. You make beautiful sculptural moments, but what I’m getting from you is that there is a further psychological activation you are after that seeks more than simply being confronted with an alluring form, but is directly related to how that form disrupts the perception of a known reality?

JMA: Yeah, exactly. It’s beginning to feel essential for me to make work that—in its form and presentation— sheds the characteristics that might lead someone to immediately read the object as an “art object”. I’m interested in creating things that one confronts and absorbs into their body and experience before recognizing that it’s an artwork—objects that are experienced candidly as parts of “the world” before being interrupted and clouded by some relative association with the historical and institutional art canon. It’s a difficult thing to accomplish without abandoning entirely the established and familiar channels of exhibiting artwork (an option I’ve been leaning into lately with bodies of work like the Puddles series). As soon as we so much as approach a space or institution built for the exhibition of art, we throw up a certain kind of experiential defense or filter, expecting that these things we’re about to encounter will (and ought only to) exist in a sort of insular and exclusive relationship to all the other artworks we’ve encountered before, confining them immediately within the tight parameters of a particular conversation—one that is broad, but certainly less broad than “human experience.”

What I enjoy about the works I’ve made so far with this in mind — the puddles and mirrors — is the sort of quiet invisibility they take on when placed outside the walls of these institutions. Not unlike some of the contracted labor I’ve done in construction or museum exhibition preparation, it’s as though the goal of the these works is that they ultimately become unseen, unassuming—if I’ve achieved the aim of the craft, you’ll likely never notice it existed. But still: you’ve absorbed it, below your cognizance, and it’s played into your understanding of the conditions surrounding you before you had a chance to realize and come to terms with the work itself. I know that might feel like a tall and rambling order, but it’s what I’m going for.

LB: Some of what you are describing is not far from the ‘provisional’ aesthetic that is widely embraced, but I do think your gestures are more pointed. I also identify with the sentiment of working in exhibition prep and have been struck by the forms that settle into place when crates, tools, dollies, blankets, etc. are lying around. These are also quite mundane situations, in most cases, invisible without very deliberate framing and placement to bring them into the light. You on the other hand, are using mundane situations but pushing them into absurdity, which requires less guided attention for the viewer, in or out of a gallery situation.

As for the mirror works, I humorously went with it! And thought, “Is it hot in here? Like, is the room hot, or is it these works?!” You’re simulating condensation and evaporation, it’s an interesting way of shaking up the viewer’s sense of the environment. What sort of space are you referring to, or rather, what is the ideal space for them to be experienced?

JMA: Yes!! You’re touching on exactly what I was trying to unpack earlier. The work is absolutely about that shaking up of one’s faith in their own senses, their learned tools for understanding the situation they’re standing in. I’ve played with these mirrors in a variety of contexts. In my solo exhibition Stay alive at Chicago Artists Coalition, I actually sealed the room off and had several warm-mist humidifiers going in the space. So when you entered, you were hit with the actual presence of intense heat and humidity before encountering these faux-steamy works. It pushed that question of one’s grasp on the environment even further. Possibly even a bit too far—which I only say because a surprising number of the folks that spoke with me just readily accepted the effect as real, taking the gestures on the mirrors’ surfaces to be something I must have done just moments before they walked in. It’s all playing into the same goal I was describing earlier: how to create a situation that leads its visitor to a place of higher scrutiny, humility, and openness to change and to the unknown and—in that sense—to a loss of control.

LB: You have exploited the multidimensional nature of reflective surfaces to achieve this. [The mop/bucket works] have me thinking of sinking in space, as opposed to floating. These spills are thresholds. Portals of celestial quicksand, stardust inverted to the floor, though someone’s floor is commonly someone else’s ceiling. In outer space there is no up. This is a slightly different effect than the small spills and puddle sculptures I’ve seen, in which a mirroring is more straightforward. But the outer space imagery seems to imply an alter-dimensional soap, or solvent.

JMA: The floor pieces in Strange Mess are definitely about this interdimensional play. I see the choice to push the reflected imagery to a mirage of something clearly impossible (a view of the cosmos from a lit, indoor space) from the more credible reflections (cloudy sky, tree branches, etc.) found in the outdoor puddles as a significant shift in the conversation around these works. With the other spill works, the fact that the reflection could be credible if placed in the right conditions/context keeps the work in the realm of quiet illusion that we were just discussing. But that’s not really where my motivations and interests lie with these celestial pieces. I feel like the push to a reflected image that immediately reads as impossible allows the piece to rest as an art object—to become a more guided space for contemplation on the phenomenon of reflection itself; on those thresholds you referred to.

I was first attracted to the effect of reflection in general for the often-overlooked quality of magic it produces as it opens things up dimensionally —the way it plays so immediately with our perception of what we see empirically as “real” or “not real”. It’s just one of many examples I go to when contemplating the ways in which we normalize and grow comfortable with our perceptions of the world around us, as though there’s anything about this life that doesn’t appropriately fall into the category of “wild hallucination.” So, to intentionally play with and skew those expectations, to say, “There’s something strange and mysterious here, now, with us in this space [and all spaces], visible if we loosen our perspective” and to make it visible through this kind of absurd, playful gesture—it allows things to feel heavy and light all at once.

LB: I love that you identified the what and why of a particular element that wasn’t working for you, even though I’m sure the audience got a kick out of it. In many ways, those works made sense in that environment. The conditions were set up so the understanding of how such objects could exist was logical. When you strip away those conditions, the cause and effect outcome is less important, it becomes more absurd. From a material standpoint, it’s more intriguing; I still don’t know how you made them [laughs], and I am okay with that. I often come back to conviction being a primary indicator of a successful affect, but you are actually aiming to create situations where being fully convinced is impossible. Like the point of the trick is that it fails, which is a different kind of magic.

JMA: Right, it’s something like that… Or maybe the point isn’t necessarily for the trick to fail, but rather for you to never realize you went to a magic show [laughs]. It changes from piece to piece, though. The aim of the works is always wholly dependent on the environment in which they’re intended to be shown. They’re variables in an equation that also includes your grasp of the environment, so as that environment changes, the rest of the equation has to shift to stay balanced.

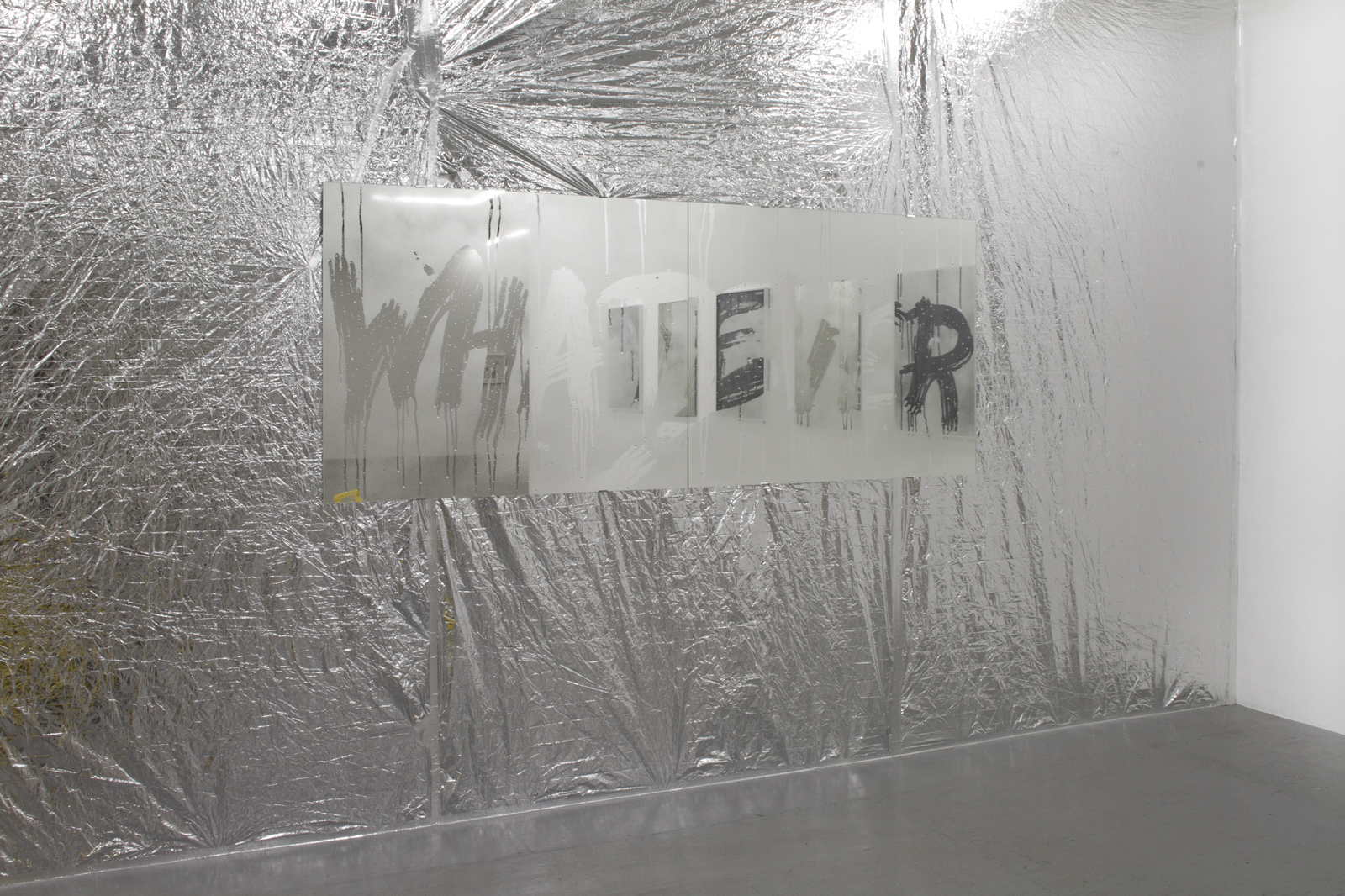

LB: Also, “Whatever”?

JMA: [laughs] Yes, whatever!! This large mirror work originally had a counterpart in Stay alive that faced it directly on the opposite wall, mirroring it (literally), and read “FOREVER”. These works were grounded in this same conversation regarding time and expectations and perspective. To conflate a concept as vast and abstract and untouchable as “forever” with a phenomenon that reads as very temporary and fleeting and conditional (condensation), but then which still in the same moment is further complicating its own reference by actually being stable or “permanent” in its material form… ahh!

It’s again about mixing things up, and doing so by pulling on two polar opposites of a certain spectrum. “FOREVER” being a nod to the end of the spectrum that represents vastness, the unfathomable, the holy, the transcendent; and “WHATEVER” being a nod to the human end, with our unique ability to not only read and analyze the apparent circumstances of life but to also regularly grow bored of them! I’m often blown away by our collective capacity to lack astonishment, bewilderment, awe…. as if we can look at any one detail of this dream of a life on a pebble hurling through an apparently endless vacuum of space and say, “Yeah, that makes sense.” To say “whatever” at all is to make a kind of false claim of control via the comfort of cool indifference—it’s saying, “I see it, I get it, I don’t care, I’m not impressed”. But these hopeful grasps at control are of course based in fear—of this unknown force that we’re born into.

LB: We fear what we cannot control, and attempt to control what we are fearful of. This is the case in numerous contexts, of course, a driving human tendency. I agree that dismissal is another way of escaping the confrontation of what we do not understand, or an unwillingness to take a position. This has me thinking of a couple older works of yours, Digging A Hole (2015) and I’m Not Worried About You (2013). As artists we can be fairly precious about the control we have over how our works operate. I assume that the mechanics of these works were controlled, but they are set up in a way that suggests things could go awry, that their form could be compromised and even dissolve.

JMA: Yeah, that precariousness is a crucial element of those works and, I would say, of the bulk of my entire history of work. The way I approach and interpret precariousness—how I choose to materialize it or centralize it in theory—changes from work to work, but it’s always there in some form or another. In the case of both Digging A Hole and I’m Not Worried About You, the sense that things “could go awry” that you’re reading was in fact very real, to the point that I was actually surprised by the resilience of both pieces. The central tree in I’m Not Worried About You was in fact balancing precariously at the point where it was hatcheted, being supported by nothing more than a handful of thin black threads that were tied to flathead nails in the wall. If someone were to so much as brush up against it, the whole thing would have collapsed.

Similarly, with Digging A Hole, I limited my own control in the piece to simply setting up the initial conditions. The motions of the balloon and shovel from there (if they would continue to move at all!), the way this manipulated the soil, the way the changing soil manipulated the wind currents coming from the fans…. the whole of this ecosystem was out of my control. The fact that it remained in persistent balance with the little dance it choreographed itself into for the full several-week run of the show was an impressive feat to me. But, back to your point—it’s the palpability of that precariousness that’s most important. Like, here is this situation that is so fragile and temporary and just barely hanging onto existence by a thread of its own flawed nature. And here we are, serendipitously alive and present in the same moment, able to catch a glimpse of it before it passes. It feels important for us to confront precarity in this way. It’s a force that I believe can really elicit empathy and humility and gratitude — as though we can see and feel the same kind of miraculousness in our own ability to avoid falling into chaos.

LB: This is probably a good opportunity to bridge these concerns with your most recent project at Heaven Gallery, Outstanding Balance, which is another take on precariousness, but from the vantage points of economic and interpersonal mortality. I’ve been really struck by how astute you are in naming your projects. The titles of your shows are simple and direct, yet engage the content of the work on many levels. This show seems to be a nice, if not natural progression from the work we’ve been discussing, yes?

JMA: It’s definitely another thread of this same conversation — drawing together these mundane and uniquely human concerns with contemplations of the cosmos or vast stretches of geologic time. Trying to contextualize and draw attention to these “vantage points of economic and interpersonal mortality”; to the underlying, broader truth of our shared condition; to the impermanence and the mystery of it all. Letting the precariousness and absurdity of our egotism show, humanizing our collective fear, and hopefully in the process giving us a bit of respite from the paralyzing, short-tempered trend toward polarization that seems to be defining our present-day socio-political environment. Along this current, I try to allow the work to open up onto safe grounds for playing with and redetermining one’s sense of value, whether it be economic, social, philosophical, spiritual, etc…

And yes, the titles always prove to be important in these kinds of gestures. In the case of Outstanding Balance, I feel a reading of the phrase itself serves as a perfect example of how our immersion in economic and interpersonal constructs can so easily skew our perceptions, divide and isolate us, and in the process begin to take control of our emotional and psychological responses. How sad to think that “outstanding balance” is a phrase any of us would recoil from! [laughs]

Featured Image: A partial view of Jeffrey Michael Austin’s recent solo-exhibition “Outstanding Balance” at Heaven Gallery. The works pictured here include (from left to right) a faux-steamy mirror, a California Redwood sapling placed under a hanging grow light in a mound of soil and ashes from the artist’s personal debt statements, the floor-based mop bucket spill work, a wall-hanging sculptural rendering of a past-due debt statement made from clear rubber and meteorite fragments, two life-size figures dressed in grey chemical hazmat suits frozen in an intimate embrace, and two newspaper front pages respectively announcing the presidential election results of 2008 and 2016, the text redacted with black paint to reveal only the word “peril” on each sheet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Lyndon Barrois Jr. (b. 1983, New Orleans) is an artist and educator based in Maastricht, Netherlands. He received his MFA from Washington University in St. Louis as a Chancellor’s graduate fellow (2013), and his BFA in painting from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore (2006). He has been a teaching artist at Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago, and has served as adjunct faculty member in drawing and design at Washington University in St. Louis, and Webster University, respectively. He is the former Museum Educator at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, and is currently an Artist-in-Residence at the Jan van Eyck Academie.

Lyndon Barrois Jr. (b. 1983, New Orleans) is an artist and educator based in Maastricht, Netherlands. He received his MFA from Washington University in St. Louis as a Chancellor’s graduate fellow (2013), and his BFA in painting from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore (2006). He has been a teaching artist at Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago, and has served as adjunct faculty member in drawing and design at Washington University in St. Louis, and Webster University, respectively. He is the former Museum Educator at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, and is currently an Artist-in-Residence at the Jan van Eyck Academie.