Laleh Motlagh’s work arrived at a time when I didn’t know you needed it. When I first met Motlagh for a studio visit and to see her exhibition, Contemplation, at Chicago Artists Coalition (CAC), I was in the throes of a heavy work schedule, obsessively thinking about my to-do list, and panicked by the lack of hours in the day to complete everything that I needed and wanted to do. I was overworked and overwhelmed by the chaos of everyday life.

Despite—or maybe because of—this feeling, I was drawn to Motlagh’s work even before I entered the space. And, in a curious way, Motlagh anticipated these feelings in her exhibition. Contemplation cultivated an immediate sense of calm; it doesn’t function as an escape from the world around us. Rather, it gives us the ability to recenter. Through her own story, Motlagh reminds viewers about the importance of mindful reflection.

Motlagh’s practice focuses on the boundaries between humans and nature as well as the geopolitical implications of belonging. In Contemplation, she explores the duality of belonging and displacement in the context of physical and political borders, using the presence of flora as an expression of familiarity, isolation, and solidarity.

My conversation with Motlagh dives deeper into Contemplation and its development during her one year BOLT residency program at CAC. It took place in person with some conversation via Google Docs. This interview was edited for clarity and length

Livy Snyder: Laleh, you just finished the highly competitive BOLT residency at the Chicago Artists Coalition (CAC). How do you feel?

Laleh Motlagh: It was an incredible and intense experience. Made lots of new works, had amazing studio visits and met many people, and had a successful solo exhibition. I am grateful for the opportunity.

LS: I’m glad to hear it was such a fulfilling experience! When we first met at CAC, we actually entered your studio before your exhibition. It was truly a lovely space filled with plants, a fish tank, a little bed for your dog, objects found in nature, and a collection of hair. You also had some studies of the plants hanging on the wall. What was your mindset going into the studio space? How did your interaction with it foster ideas for your residency exhibition, Contemplation?

LM: My studio has always been lively. It’s a space where elements of multiple species co-reside: about 90 houseplants, a fish tank with three fishes and 50 snails, a collection of hair/fur—my hair, pig hair, Honey’s fur (my dog), coyote and fox fur, pigeon feathers, etc. Also, delicate elements from nature: two bird nests, a honeycomb, cow and chicken bones, a small wood stick with insect trails, etc. These objects that had life in them at some point inspire me. I look at them every day. I specifically asked for a studio with windows. I knew I wanted to work with my houseplants and needed them to grow and thrive in the studio. I wanted them to be happy.

The drawings are titled In Search of Silence. I started my works with plants with these drawings. I drew most of my plants in the studio. When drawing, I am not looking at the paper, but looking at the plant only… to create a direct connection to my non-human collaborators. The exhibition was the result of nine months of intense thinking and making. I spent a lot of time in the studio, drawing, sketching, touching, and feeling the plants. I listened to them, to their quiet voices.

LS: There is a significant transition from animals to plants in your recent exhibition. I feel like it’s a logical expansion in your practice since you are interested in non-human species, but was there something specific that triggered the decision to focus on flora?

LM: The idea of working with plants came to my mind because of three different things that happened almost simultaneously.

1. I finished three residencies in Europe right after MFA in summer of 2021. During the residencies, I made works, collaborated with cows—the works were intense. When I returned to Chicago and got accepted to the BOLT residency, I needed a bit of distance from the animal works.

2. I have had these houseplants for more than a decade. On the other hand, I have moved 10 times [in total] (both apartment and studio) since the Spring of 2019. And, of course, have moved all the plants with me… from one place to another. We became very acquainted. I was curious to know what that relationship is and what it could look like? Me and 90 houseplants!

3. In Fall of 2021, I felt like the world is going absolutely insane. I couldn’t handle it anymore. I needed some quiet space. I needed to slow down. Plants are both quiet and slow, at least per our perceptions.

Therefore, I started thinking about making new bodies of works… collaborating with plants. They are also non-humans, but [it’s a] very different dynamic between me and the plants vs. me and the pigs, for example.

LS: I am very impressed by your ability to keep the plants alive while moving them around between spaces! If it were me, they would have never survived!

Your word, “collaborating,” is an interesting way to describe your work with plants. It reminded me of the book, “The Mushroom at the End of the World” by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing who uses the word “collaboration” when writing about multi-species landscapes and survival on Earth. I am seeing some parallel themes between the book and how you are thinking about plants, borders, and survival. Have you read it by chance? Are there other texts that shaped your approach to working with a range of species?

LM: I have not read Tsing’s book yet, but many have recommended it and it’s definitely on my list. I am a very slow reader. And I read cover to cover… everything. I make notes and research the ideas, terminologies, images, etc. So, it takes a long time for me to finish a book. Currently, I am reading “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants” by Robin Wall Kimmerer. I love how she talks about hidden language… encouraging us (the humans) to listen deeper.

LS: I will have to read that! Deep listening is a topic I’ve been thinking a lot about lately too. I feel we participate in a lot of passive listening (how can we not with so much stimulus!) but to me, deeper listening is oriented towards a more communal awareness. It is also noteworthy that your exhibition is silent and I see that as very purposeful and working towards generating a space for listening. In a quiet space, we start to notice the sound of our own breathing, our shoes brushing against the floor, our clothes rustling as we move, the creaks of the building, etc.

LM: Definitely. Silence is a big part of the installation and all the works. I think we can achieve a lot with just silence and listening. We can interpret ideas in different and new ways… without the boundaries of known language. I’d really love to expand on these ideas for the next projects.

LS: The first works the viewer encounters [in Contemplation] is the series of drawings, Obscurity. The drawings have subtle organic lines that mimic the contours of a monstera—a plant frequently present in Contemplation. I felt very emotional when viewing these works! They are powerfully quiet. Can you speak to your process transforming the gallery space and developing this series of drawings?

LM: Thank you, Livy. “Powerfully quiet” is a great way to interpret the works. From day one, I wanted to transform the gallery space, engage with the space and do something different. Also, the space I was given was too big for what I wanted to do. Therefore, I decided to build a wall and create a small and intimate space where the works can exist and have sort of a dialogue with one another. Honestly, it was a risk to leave a large portion of the space empty and only utilize a corner of the gallery for the installation. But I have always pushed myself to take risks in order to grow. I am glad I took the risk. The void became a huge part of the installation and was a huge success.

I got to Obscurity after six months of making other drawings and paintings. I started with some blue and brown paintings. All were loud and didn’t speak of quietness. It took six months of creating works and thinking about reduction. When I made these light drawings, I got to the slowness and quietness I was searching for.

Obscurity invites the viewer to slow down. To be with the works for a few minutes, to spend time and to contemplate on quietness. At first sight, they look like blank pieces of paper, framed in a row. The lines are challenging to see and they require little bit of engagement from the viewer. After a few minutes (when the eyes adjust to the light), [the lines] start to appear.

Also, a beautiful surprise happened. Because the larger space is all left empty (a big void) and since there are no works on the walls, the floor became very noticeable. There are four lines that come out of each wall and meet at the center of the room. They almost mimic the lines of the drawings… or they can be read as the roots. I loved the surprise.

LS: I definitely felt the effects of the reduction technique in the drawings, my breathing slowed down significantly when viewing the works and I felt a rush of calm. Seeing these works evokes a thinking that is different from the chaos of everyday life—a type of thinking that reinforces slowness, as you mentioned, or a stillness.

And speaking of stillness, your piece, Quiet Chaos, is a performance video of you sitting very still and upright on the beach holding the monstera plants. You are also holding a stick with a white scarf wrapped around it as a symbol of political protest—specifically, you are responding to Mahsa Amini’s death on the 16th of September which resulted in the most recent uprising in Iran and the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. Despite your physical distance from the protests, the inclusion of this stick with the hijab wrapped around it is an expression of solidarity. I am sure there are a lot of feelings about the current situation in Iran and I am interested in hearing more from you about this gesture.

LM: Quiet Chaos is an important part of the installation. This piece was the most challenging one and took the longest to make. Initially, I was thinking of collaborating with the monstera but didn’t know how or what it would look like. I chose the monstera because I found out that it is a very typical houseplant. So, there is a sense of familiarity for the audience. However, the monstera is not local to here (U.S.), and definitely not local to Iran. But here we are sitting on a beach… where I don’t belong—I grew up by the mountains—and the monstera doesn’t belong (they’re local to central and south America). So there is a notion of displacement and not belonging. However, she is out of her pot, her roots are exposed… she is not contained, I am not contained. We both are uprooted.

For the past few years, I have been wearing a scarf in my performances. That has been my way of bringing up my conservative cultural background and the religion I grew up with in Iran. The first time I shot Quiet Chaos, I went to the beach on a weekend. It was crowded and kids were running around behind me. It was a sunny day, bright blue sky, and I was wearing the scarf. A week later, Mahsa Amini was killed in Tehran. I looked at the footage and thought to myself: “This doesn’t feel right. I cannot wear the scarf now.” Therefore, I went back to the beach for the second time. I chose a day in the middle of the week, so there was no one on the beach. I chose a cloudy day, and I tied the scarf to a piece of wood stick, a symbol of protest and revolution for women in Iran who have sought freedom with every fiber of their being.

This symbolic element of the movement started about five years ago in Iran. Women took the scarf off their head, tied it to a piece of wood and stood on the side of the street as a sign of protest against compulsory hijab. They all got arrested, of course. So, for me, this was a way to respond to the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement that was happening in my home country of Iran, but in a very quiet and subtle way.

LS: The way I see it, the stillness of the composition and the way your gaze meets the viewers is very powerful. I also see how the lack of movement from your body draws attention to the sensitivity of the body and internal experiences (to signal contemplation) but also, since nothing is ever truly still, other movements are emphasized, such as the scarf, the leaves of the monstera, and your hair that blows in wind simultaneously suggesting an interconnectedness.

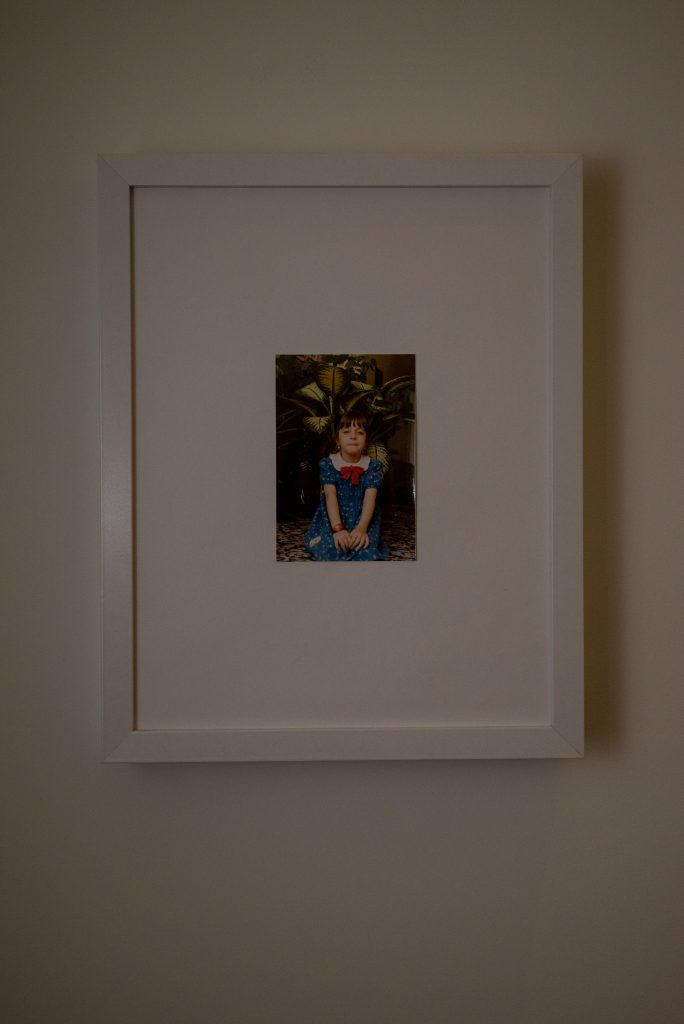

LS: And something else that strikes me is the proximity of Quiet Chaos to another artwork, a small photograph, Untitled. From what I understand, this is a photograph of you as a child in Tabriz, Iran where you grew up. Similar to Quiet Chaos, it has the monstera in the background and you are sitting in a similar position to Quiet Chaos. Both works are hung close to a corner, almost inches apart, so there is an obvious relationship I want to explore based off the positioning of these pieces and how it relates to notions of belonging and borders of physical and political space.

LM: During my research, I kept asking myself “where does this interest come from?” My interest in houseplants. I found several photographs of me in my childhood home in Tabriz, Iran that were surrounded with beautiful but typical houseplants. It was very clear that I grew up with them, just never realized it until recently. I chose this photograph specifically because the leaves of the monstera are visible on the left side. I am also sitting in the same position as I am sitting in the video. For me, the two works are in a close dialogue with each other. It’s the past in Tabriz, the present in Chicago, with a mutual non-local houseplant.

LS: I see a connection between the protest gesture and the image of a young girl too. To me, it visually elaborates or hones in on who the protest is for. For an exhibition that uses a lot of reductive techniques, there are so many layers to unpack between human and non-human species (the monstera plant), as well as the current geopolitical climate and the implications of belonging and isolation. What really stands out to me is the introspection and resilience present in this exhibition.

While there is a lot to take in with Contemplation, I also can’t wait to see what’s next for you now that the residency has ended. Would you be able to share any details about what you are working on now?

LM: Thank you Livy. I spent months thinking about this exhibition and every single element in it. I am glad it portrays introspection and resilience.

I will be heading out to Mexico City for a performance, part of Lit & Luz’s MAKE performance festival. I will be re-performing Do You Hear? I am also working on new pieces that will be part of CAC’s exhibition at EXPO. I am working on the same ideas, but in a very large scale. Can’t wait to show them. Also, Quiet Chaos will be part of a group show in Woman Made Gallery opening on May 6th that is centered around the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement.

Laleh Motlagh (b. Tabriz, Iran) is a Chicago-based artist and educator. Her work has been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions in the U.S., Mexico, Germany, Italy, and Iran. She was the 2022-23 BOLT resident at Chicago Artist Coalition. She was previously artist-in-residence at Nature, Art, and Habitat Residency (Taleggio Valley, Italy), Kunsthalle Bellow (Techentin, Germany), Institut für Alles Mögliche (Berlin, Germany), and House of Nature (Wald, Germany). She received her MFA from the University of Illinois Chicago in 2021.

About the Author: Livy Onalee Snyder is a writer currently based in Chicago. Her work has appeared in Sixty Inches From Center, Ruckus, Newcity, Tiltwest, Denver Art Review: Inquiry and Analysis (DARIA), and interviewed artists for Black Cube Nomadic Museum. Currently, she holds a position at punctum books and advocates for Open Access. Read Livy’s writing for Sixty here.

About the Photographer: Tonal Simmons, they/them, is a Black queer non-binary artist who is a writer, photographer and painter. Their photography and painting seeks to examine the similarities between flowers, growth, and Black queerness. While their writing explores the idea of DEI within art, creating w/chronic conditions, & lack of access to art for Black and brown creatives. You can check out their personal work at www.tonalscorner.com