Treated with fumes and mercury vapor, the silver-polished metal plate is exposed to the light of a sunny Parisian day and reveals a latent image on its mirror-like surface: the curve of a cobblestone street leads the eye down rows of various-sized structures, toward a far-off vanishing point in the cityscape. Legible in the foreground, out in front of what appears to be a residential building, we see two figures miniaturized within the sweeping panorama.

Captured by Louis Daguerre, inventor of the eponymous daguerreotype technique, this 1838 photograph, titled Boulevard du Temple, is believed to be the first picture ever created of city space and daily urban life. With its elevated perspective looking down and across this vista, Daguerre’s photo situates the viewer as an observer who is simultaneously in the city but also looking at it from some remove, as if through a window. The wide angle and sense of distance allow the viewer to consider the scene aesthetically: the contrast and quality of light, the atmosphere, the architectural forms. At the same time, the anonymous people in the lower left corner reveal something deeper: one is a shoe shiner, the other his client; this is a picture of labor, and of social relations.

Daguerre’s initial city vision set image-making on a path that continues today in depictions of daily life and the built environment. Photography often traverses urban space through avenues of poetics and politics – poetic in the sense of contemplating aesthetics amidst the rhythms of the everyday; and politics through documenting the city as a “text” in which we can read and interpret the dynamics of historical and contemporary inequality, injustice, exploitation, and unbalanced distribution of power and resources. These poetics and politics constantly meld in our lived experiences of the city. Chicago, of course, is no exception to this, bounded by both its renowned architectural history and ongoing institutional racism, segregationist urban planning, gentrification and displacement.

What follows is a brief, and in no way comprehensive, look at how juxtapositions of Chicago’s spatial poetics and politics have been documented photographically through the historic work of Yasuhiro Ishimoto and contemporary work by Clarissa Bonet, Lee Bey, Tonika Johnson, and Sebastián Hidalgo, each with their own vision of our city.

The transnational photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto first arrived in Chicago in 1945, resettling here after he and his family were imprisoned in Colorado for three years when the U.S. government placed 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II. Having first experimented with photography at the Amache camp, Ishimoto enrolled at the Institute of Design here and learned from the likes of László Moholy-Nagy, Harry Callahan, and others, who encouraged him to use photography to document the city.

Immersing himself among marginalized communities in Chicago, Ishimoto witnessed the effects of racial segregation, which he sought to document through landscape images and empathetic portraits of residents. The exhibition Someday, Chicago, on view through December 16th at the DePaul Art Museum, features forty of Ishimoto’s photographs of Chicago from this period of his work in the 1950s and 1960s, including selections from a later set of over 200 images created between 1958-1961 that were produced for his book Chicago, Chicago.

The prints on view in this exhibition not only demonstrate Ishimoto’s mastery of the photographic craft, but also his expressive explorations through a keen eye for light and texture in urban spaces: the sculpted scale of glass and steel, the thin section of waning daylight that illuminates a downtown hotel’s neon facade, the crunchy detail of snowy boots on neighborhood sidewalks. In the back of the exhibition, a small set of color prints also illustrate Ishimoto’s decades-long experiments with abstract imagery assembled from multiple exposures of landscapes and architecture in various locations.

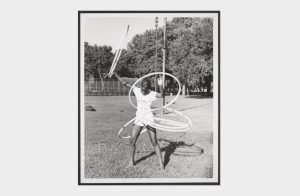

The black-and-white photos, which comprise the bulk of his work in the exhibition, contrast scenes of under-resourced neighborhoods with the glitzy structures and skyline of the downtown core being transformed by so-called “urban renewal.” While his images of the built environment tend to emphasize its formal qualities, Ishimoto maintains a subtle social commentary by giving equal weight to everyday moments such as the jubilant play of neighborhood children, or to public protests calling for desegregation, housing justice, and other civil rights.

At first glance, Clarissa Bonet’s City Space series seems to borrow some of the modernist vocabulary of Ishimoto, Callahan, and their colleagues, as her photographs explore downtown urban space in Chicago through light, shadow, color, composition, and texture. However, whether through tiny clues or our own careful investigation, we may come to discover that these works traffic somewhere between composite images and strict representation. As reconstructions based on real events or chance encounters that the artist experienced and then later staged and re-created, Bonet’s images complicate the idea of a photograph as document.

Approaching the urban environment as both a physical space and a psychological space, Bonet’s methodology emphasizes how the city may at times feel overwhelming, imposing, mysterious, or confounding, as we navigate amongst skyscrapers, deep alleyways, canyons of light and dark, always under the watchful eye of capital and CCTV. Like high-contrast scenes that evoke the psychic drama of noir genres, here life in a city core dominated by tourism and business becomes imbued with a sense of isolation, anonymity, dread, or monotonous boredom.

As a photographer, writer, and architecture critic, Lee Bey also directs his camera toward Chicago’s built environment, but with an important caveat: instead of the popular boat tours and exquisite vistas of the city’s legendary downtown structures, his series Chicago: A Southern Exposure draws our attention to under-appreciated architecture and design elements on the South Side – including works by famous names such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Daniel Burnham, or Eero Saarinen. A native of the South Side, Bey has created a visual survey that considers a variety of institutional, residential, and everyday structures and spaces which have been undocumented or overlooked due to racism, classism, and prejudiced conceptions about these areas.

Many of the negative portrayals and stereotypes about the South Side have been perpetuated through photography itself, in biased or misleading journalistic reporting, or the day-tripping ruin tourists seeking images of abandoned buildings and poverty that offer very selective impressions of those neighborhoods. By turning his camera toward the vibrant structures that other photographers ignore in their single-minded hunt for decay and vacancy, Bey both assembles an important counter-narrative and contributes to an ongoing record of the South Side’s cultural legacy.

Furthermore, although Bey’s images are predominantly focused on architecture, it is important to recognize that these are living spaces of circulation and daily routine for (predominantly Black) residents – as seen, for example, in the passing cyclist, the cars parked out front, or the customers coming in and out of the cleaners.

In a similar vein to Bey’s work, Tonika Johnson’s images also help construct a crucial counter-narrative to combat false characterizations of the South Side. A native of Englewood, Johnson began photographing her neighborhood in 2006 and eventually developed two complementary projects, Everyday Rituals and From the INside, which document and revere the joys and beauty in her community, encountered in spaces and social gathering spots such as sidewalks, street corners, stoops, lounges, churches, or parks. These images provide the community a chance to recognize themselves in an intimate archive of the neighborhood created by someone with direct connection to that place.

Johnson’s most recent exhibition project, Folded Map, confronts Chicago’s violent legacy of racial and residential segregation by displaying photographs of various disparities that persist between the South and North sides. Beyond the photographs, Folded Map includes a critical social and conversational component, bringing together residents from opposite south and north ends of the same street, from different neighborhoods, to get to know each other and discuss their lives.

Folded Map is currently on display through October 20th at the Loyola University Museum of Art. To read more in-depth about Tonika and her Folded Map project, check out her recent interview by Ireashia Bennett as part of Sixty’s Envisioning Justice initiative.

At the time Daguerre made his famous picture in 1838, the Boulevard du Temple was an area known for its many edgy theaters, including one where he worked as a stage designer. Today very little remains of the cityscape that appeared in Daguerre’s image: between 1853–1870, under the commission of Emperor Napoleon III, Georges-Eugene Haussmann oversaw the razing and reconstruction of the majority of central Paris. Districts around the Boulevard du Temple and elsewhere were thoroughly demolished, and ethnic minorities, poor, and working-class residents were forced out to the peripheries of the city. Carried out under the auspices of “urban renewal”, this transformation of 19th-century Paris was, in some ways, a template for the gentrification and displacement we see happening in Chicago and other major cities today.

Sebastián Hidalgo is a native of Pilsen, one of the neighborhoods being most drastically affected by current waves of gentrification in Chicago. Combining aspects of documentary, journalism, and visual art as vehicles for narrative storytelling, Hidalgo has been engaged in a long-term photo essay about Pilsen entitled “The Quietest Form of Displacement in a Changing Barrio.” Growing directly from his roots in the neighborhood and his community relationships, Hidalgo’s images focus on the physical, emotional, and cultural impact of displacement, as well as the political neglect (i.e. opportunistic aldermen who side with developers and sell out the majority of their constituents) and violence that accompany gentrification.

The notion of displacement as a “quiet” process carries a lot of weight through Hidalgo’s pictures. Gentrification is a slow, insidious unfolding over decades, mostly under the surface, until it suddenly reaches a point of hypervisibility (usually of imposed whiteness and upper middle class consumer culture) and crosses a threshold where long-term POC residents begin to feel pushed out and see their neighborhood as haunted by strangeness or trauma, or a sense of isolation in a place they no longer recognize as home.

Additionally, this quiet, slow violence is epitomized in the narrative of Casa Aztlan, which Hidalgo has included in his documentation of Pilsen. Formerly a community center and major gathering space for the local Latinx community, Casa Aztlan’s exterior was adorned with some of Pilsen’s oldest murals as homage to famous artists and activists from the neighborhood. After the building was bought in 2017 by developers seeking to convert it to luxury apartments, the community erupted in protest when the owners had the murals painted over in a drab gray. In the face of such acts that threaten to erase and displace Pilsen’s identity as a Latinx barrio, Hidalgo’s work helps to preserve a record and archive of that community and its cultural footprint in the neighborhood. His images are currently on display in the group exhibition Peeling Off the Gray, through February 2019 at the National Museum of Mexican Art.

This article is presented in collaboration with Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy through more than 30 exhibitions, as well as hundreds of talks, tours and special events in 2018. www.ArtDesignChicago.org

Featured Image: Clarissa Bonet, Proximity, 2014, pigment print. From the series City Space. Two silhouetted people lean up against opposite sides of a tall green pillar, as they take a cigarette break outside of a reddish-pink downtown building. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Greg Ruffing is an artist, writer, organizer, and curator working on topics around the production of space at different scales – from the macro level of sociopolitical structures and architecture in the built environment, down to an emphasis on community, collaboration, and exchange on the interpersonal level. He is the Photography Editor at Sixty Inches From Center.