The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is an initiative that highlights Chicago archives and special collections that give space to voices on the margins of history. Led by Chicago-based writers and artists, the project explores archives across the city via online features, a series of public programs and new commissioned artwork by Chicago artists. For 2018, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation has funded a series of pilot projects pairing three artists with three archives around the city: Media Burn + Ivan Lozano, the Leather Archives & Museum + Aay Preston-Myint, and the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection + H. Melt. This series of articles will profile these featured archives and artists over the course of their collaboration, exploring the vital role of the archive in preserving and interpreting the stories of our city as well as the ways in which they can be a resource for creatives in the community.

For this installment, we sat down with Catherine Grandgeorge, the archivist from the Newberry Library’s Chicago Protest Collection. The Chicago Protest Collection builds on the Newberry Library’s strong collection documenting social and political activism in Chicago and the Midwest and seeks to collect “an enduring record of the many individual voices and personal expressions of Chicagoans participating in public demonstrations in the city or elsewhere.” It accepts physical protest ephemera as well as digital donations. The following interview has been edited.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes: Thank you for showing me around! So let me start at the beginning. How did you become an archivist, and how did you get involved with this archive?

Catherine Grandgeorge: So I’ve been at the Newberry for five years now, and I started as a library assistant and was in library school when I was working here. I was fortunate enough to get on the archives team after a couple of years. I didn’t focus on that in library school. I actually thought I wanted to be a cataloger. But for my capstone project for grad school, I worked on a project for the archives team here where I created different little mini records — we call them stubs records — to describe our unprocessed collections. … So I kind of fell into archives, but it’s definitely the right place for me. Then in January 2017 my former boss, Martha Briggs, got the idea to start a modern protest collection, and she just kind of said, “Hey, Catherine, will you help me with this?” We’re a small team so we all just kind of help with everything, but we kind of take the lead on certain things. At the time I was working on an exhibit with her so we just kind of fell into working on the protest archives as well.

JPC: Do you know why she wanted to start this archive or why this archive got started?

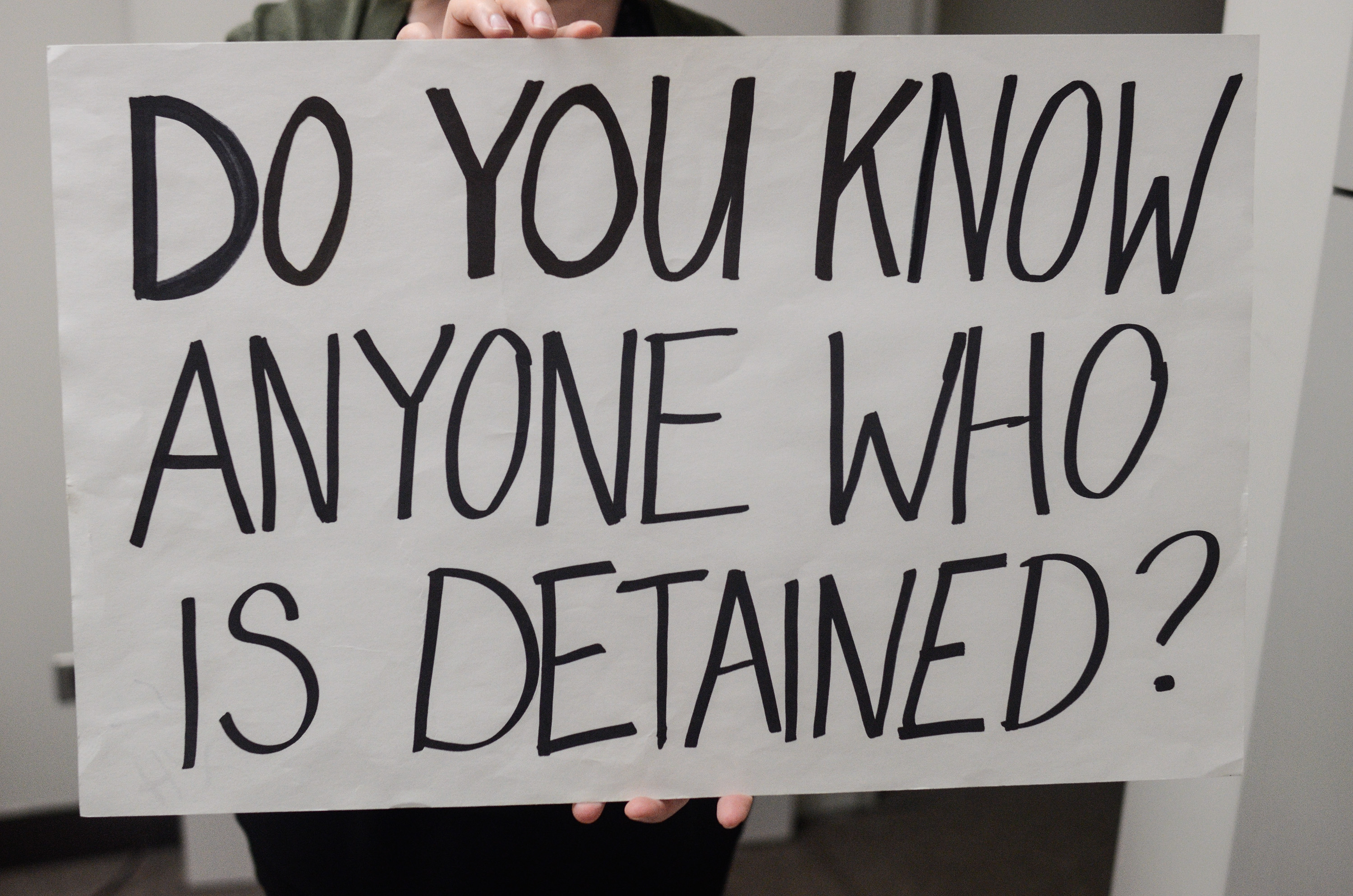

CG: We have a history of collecting what we term social protests — or, sorry, social action collections — that’s the kind of subject that we assign to this, particularly in Chicago and the Midwest. So I think she really just wanted to build on that and also just kind of capitalize on the more modern movements that people were starting up. I mean these things are going on all the time, but I feel like once the last election happened, people were just kind of in a particular spot, and they really wanted to document things. Typically here, people don’t think of the Newberry as having more modern collections because we have, you know, a lot of medieval stuff. Even our team, we’re “Modern Manuscripts,” but we define that from being 1700 to the present, so it’s still a really big thing. And to also let people know that we’re still actively collecting this type of stuff. The Newberry’s not always known for collecting those. Typically, things are donated here, and we do have funds to purchase things, but a lot of times, even donations or purchases, those are waiting for somebody else to build a collection. It’s either a collector that’s collecting ephemera, someone’s research files, an organizational group’s records, or an individual’s papers. And in this case we really wanted to get in and get the things as they are being created because they’re so ephemeral. People are creating these signs for marches and then just throwing them away. Or you know, they keep them for their own memories. And so it just seems like a really good opportunity to reach out to people to get these things while they are being created, rather than waiting for somebody else to build a collection and then donate it to us in the future.

JPC: I think one of the things that is really interesting about this archive is that we talk about crowdsourcing things and a protest is literally a crowd. It’s literally crowdsourced. So how does that fit into your work as an archivist? Does that change things for you or how you manage the archive?

CG: Yeah, it’s really new for us because this is really only the second time that we’ve used crowdsourcing as a method to get things. It was kind of learning as things came in. We kind of had to tweak things, like, you know, when people donated things we asked them to fill out a little provenance sheet to keep with the materials because normally when something is donated as a batch, we get to talk to the donor and we get that information or you can email them. But in this case, it’s hundreds of people donating one thing and we had to adapt quickly, like we forgot to put the date on the provenance sheet. So those little learning moments were like, “Oh, that’s something we should really be capturing.” It was kind of an evolving process. And it really created a lot of questions of how to deal with it and how do you arrange it, how do you describe it. Because, I mean, that’s the case with any archival collection, but I think this one’s a little more complex partly because it’s crowdsourced.

JPC: You had mentioned wanting to digitize the collection eventually and then within that, I was wondering if you might also use crowdsourcing to describe it, to get the metadata?

CG: We hadn’t really considered that, but that is a good idea. I should also mention there’s a digital component. It was really the first time ever that we’ve crowdsourced digital content. A lot of libraries and institutions are grappling with what to do with their born digital collections right now. It’s kind of a big thing in the field and we’re in the same boat. We have collections that need to be dealt with. So this was also a mechanism to think about what we could do with that type of content. It already has kind of been described because people filled out a form when they sent pictures or something, so we captured that. With the physical stuff, in terms of digitizing it, we were thinking that if we had pictures that people can browse of the signs, it would be much easier than trying to serve it up in the reading rooms. Because there’s hundreds of pieces of things and it’s not like if someone comes in and says, “I want to see all your Women’s March posters.” That’s so many that it’s really hard to do that. So we don’t have a timeline for that. I mean, it also involves multiple departments here at the Newberry, but, ideally, I mean, I think that would be the best way to do it. But I like your idea for transcribing.

JPC: Have you seen any benefits or drawbacks to the crowdsourcing approach to archiving?

CG: Yeah, I think benefits are that it is just really open-ended. Well that’s actually a benefit and a drawback. For example, with the digital images, we really struggle with how to word the whole copyright permissions thing. It’s a copy of someone’s photograph. We were not the sole owner of that image or whatever. Obviously it was also just trying to explain that once you give this to us, we have the right to reuse it. And I’m no copyright expert, so I think that was a really big challenging thing, and, I mean, again that’s with all our collections. But I think because this is coming from so many different people it’s really hard to explain in a way that might make sense and also covers the bases.

I mean also with crowdsourcing you just never know how much stuff you’re going to get. For the Women’s March in 2017 we got hundreds of things. For the Women’s March in 2018 we just had maybe two or three things. I think the momentum just kind of died a little bit. You know we just hit at the right moment that first year. So yeah it’s kind of a toss up and we previously had done a little bit of a crowdsourcing initiative. We have a small Black Lives Matter collection here in Chicago and that’s also very small because it’s really hard to get the message out. … The other challenging thing with crowdsourcing is our goal really was to just document what’s happening. And that means representing across the political spectrum but we really haven’t gotten anything that is more conservative or more right wing. … So you just kind of have to accept what people donate. And another issue with the digital stuff is people were submitting like memes and other things that they didn’t create.

JPC: Ohmigod! People sent memes?

CG: Yes, because I had to go through all the 900 things that were submitted and you know it’s like, well you didn’t create that, so we excluded those from the collection. They’re just not appropriate. So you just never know.

JPC: Would you include a meme that somebody did create?

CG: Yeah, I think so. But these were like clearly like phone screenshots that someone submitted. You don’t have that much of a problem with the signs and other physical ephemera.

JPC: So what protests are represented in the archives? You said that there’s a Black Lives Matter collection?

CG: Black Lives Matter is technically a separate collection, but it is part of that larger social action thing and it was kind of our first. I definitely bring it up when people are interested in the protest collection because it’s very closely related. But in terms of the way we manage archival collections, we kind of see this as a separate one. Really it was the precursor to this kind of idea and even some of the digital photographs are kind of tied to some more Black Lives Matter movement events and other things, but the kind of generic protest collection that we’ve created currently contains stuff from the Women’s Marches, both in Chicago and Washington D.C., the March for Science in 2017, the immigration ban protests also in 2017. I think there might be a couple items from the Tax Day stuff that happened and then a couple other miscellaneous that we got just a handful of items from some of the gun violence protests and everything but not a ton.

JPC: Can you talk a little bit about how you organize the items in the archive?

CG: So our initial sort was by event chronologically, starting with the first Women’s March because it’s kind of what kicked it off. Then we’re trying to keep it focused on Chicago and the Midwest, but the Washington D.C. March was so big. And there are a lot of Chicagoans travelling there. The things there kind of represent Chicagoans elsewhere. It’s kind of our take on that. But generally they’re organized chronologically by event and then by type of item. So we have the posters, banners and things like that together and then the smaller physical thing like the textiles, buttons, stickers, pieces of paper. … They’re also organized by size because when we eventually store them in our climate controlled stacks, it’s just easier to group the larger things together and the smaller things together.

JPC: So right now is that archive open to research? Are people coming in?

CG: Yeah. Here at the Newberry all of our unprocessed collections we term as being “open,” but we ask people to make an appointment. So that’s kind of the situation with this collection right now. I’d be happy to facilitate people willing to come in and use it for research purposes but because there are so many things, I have to kind of talk with people and narrow down what they want to see and bring it out. But that goes for anything. We’re really proud of that because a lot of institutions just lock away their things that don’t have a description and we really try our best to let people look at things.

JPC: That’s really cool! So I was wondering, some of the protest signs are so creative. Do you view them as art? Are people studying them as art?

CG: Well, it’s interesting because it’s such a new thing that we really, we don’t know why people are going to come look at them. But I really think that that is one reason that people are going to look at these kind of artistic expressions, especially even in the movement. Recently I was reading a research proposal for someone looking at women’s needle samplers, where they were learning how to stitch and stuff. They’re researching that, and it’s like, in the future, wouldn’t it be cool if someone was doing the same thing for pussy hats? So there’s that kind of anticipation of how people are going to use it in the future. So I think not only does it have that historical aspect, I think there’s a lot of cultural references that are happening right now. … What issues are people describing on their items and then the very object based approach like physically what is this? You know there’s a couple things that are really nice like screenprint kind of things and we all have a really strong collection here of the history of printing and book arts and things like that. So I think it ties in. In the future there’ll be some interesting in there.

JPC: Have you worked with artists in the archive ever before, either in this archive or any of the other ones that the Newberry has? And are there any things that come up with artists as researchers that maybe are kind of different than the way that other researchers work?

CG: Yeah, here and there. I’ve worked with various [artists]. I don’t have a super public-facing role but I do help out when researchers come in or are looking for something in particular. Really the first thing that comes to mind is dance research because we have a really strong dance collection, and that’s one thing I’ve been focusing on in the last two years. With that there’s the whole issue of the audiovisual. And I think when it comes to artistic expression, it’s not just as simple as opening a book. You know, it’s looking at things in a different way and the same with audiovisual. When you’re trying to describe a video clip of a whole dance company you have to think about all the different access points that people are going to be trying to get at that. Like all the dancers names and the piece name, and I kind of see these things as similar when we were talking earlier about how we’re going to arrange them. One of my ideas was to arrange things somewhat alphabetical by slogan because I think that’s one way people might want to access things. But then that gets really tricky when someone has written like 20 slogans on a poster. You know these are not like books that come with title pages that have kind of a more set way to describe them which is actually one thing I enjoy about working archival collections. You kind of get to make it up yourself and so I think with artist researchers in particular, you sometimes have to get more creative because they’re not always looking for that really accessible stuff.

JPC: What are some of the most unique items that you’ve seen in the collection? And do you have any favorites?

CG: One thing that really sticks out to me is this beautiful quilt that a woman made and I can show it to you. But I mean she obviously took a lot of time to create. One thing I’ve kind of failed to mention so far is one thing that we really wanted to capture was the context — why are people creating these signs, what is their story? And for some things we have gotten some personal narratives and we would love to have more of that type of thing because talking about people’s experience, it’s more than just, “Here’s a sign.” And we did get a lot of things from older suburban white ladies who are reflecting on “I’ve been marching my whole life and it is just another kind of experience.” But so the quilt is kind of from that perspective, but it’s just a really amazing piece of textile art. … And there’s a puppet that’s kind of odd. It’s only one little hand puppet that I think somebody probably carried.

JPC: Was there a narrative with the puppet?

CG: I don’t think so. But what’s kind of fun, with our digital component of it, some of these signs, especially the larger ones that stand out, we have photos of people carrying the sign because they’re so prominent. People were taking pictures of them. So there is one, I can’t say that it’s my favorite, but it’s a troll doll that looks like Trump and it’s so large that it did show up in a lot of the digital photographs.

JPC: So what has been people’s reaction to the archive?

CG: Overall it’s been very positive. We have had a couple public programs. We have a group that’s geared towards younger donors so it helps that our development department sponsored that. Analú [López, the Ayer Librarian at the Newberry] and I talked about various protest-related things in the collections. So there’s been that kind of outreach that I think has been popular, especially since, again, people don’t realize we collect that type of stuff. They’re kind of excited to see that being documented. Our social media team, there were maybe just one or two kind of more negative reactions to the collection in terms of not realizing that we would be willing to accept items from across the political spectrum, thinking that it is more liberally based. It is only because that’s who’s been donating things. But I would not say no to other things. I think that person said something like, “I don’t believe in women marching,” or something. [The social media team] did a really good job of just responding and saying like this is open to everybody.

JPC: Do you think that people have associated in their mind that this protest archive was for the Women’s March and, if so, does that get in the way of people continuing to donate?

CG: Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right because I’ve actually heard people refer to it as the Women’s March archive. And because we got that huge onslaught of stuff, that was like the first thing that kicked off. I definitely think that is what people associate with it. And we do have limited ways to kind of publicize it. Our social media people are really great and supportive of doing it but there’s only so many times you can kind of shove into people’s faces. … But there’s the March for Families happening and it would be great to have some documentation of that. We might get a couple digital things that trickle in and maybe a couple of physical things. I mean you know people are mailing things so they show up every once in a while. …

JPC: But you are still accepting things?

CG: Yeah. We really don’t know what the future of the collection is even going to look like. I don’t know if it should just be like a range of a couple of years that just kind of document what’s happening now. It’s really, “Where do you draw the line?”

JPC: And does it depend on how much space you have?

CG: I mean we definitely have a lot of space considerations. One thing I haven’t mentioned is there’s a lot of conservation issues too, especially like glitter, tape. People got really creative in the way that they were putting their sticks on their signs. You know staples, glue, duct tape everything.

JPC: How do you conserve glitter?

CG: You don’t. (laughs)

JPC: I was wondering what your selection process is like. How do you decide what you will keep in the collection or whether you need to let something go? How does that work?

CG: Sure. So kind of the first-level decision is just the very physical, what condition is it in? Obviously with our collections we can’t have any mold or water damage and actually some of the posters that were mailed to us from the Washington D.C. March were things people abandoned on the ground and were walked on. People picked them up and mailed them to us, which is great. But they were very dirty and some of them even had some mildew and stuff. … Technically it could be conserved, but we don’t have the resources to do that. And then as we’ve been talking about, there are multiple conservation concerns. The types of materials people used to create these different pieces of ephemera, so the glue and the tape and the glitter and even one of them has like a faux fur on it for the current president’s hair. I honestly don’t know how it’s going to hold up over time. So just kind of assessing, balancing what the object is trying to say, what slogans are on it — is that a good candidate to just be digitized and then get rid of the physical piece of it? And we tried to make that really clear when people were donating these things. We don’t have responsibility to keep everything. And then the other approach I’m taking is that you see a lot of the same slogans over and over … and so maybe if you look at all those together maybe the ones where somebody put more time into it or it has multiple slogans or something versus one that just has that message. So to me, that’s another way of kind of winnowing things down a little bit. But it’s really hard. I don’t like getting rid of things, but it’s part of my job.

JPC: What do you hope that people will be able to learn from or get out of this archive in the long run?

CG: I think there’s a lot of different ways that people are going to come to the collection. And I think a lot of it remains to be seen. I think it’s hard for me to even imagine all the different ways. But I think, hopefully, it will serve to represent some of the individual voices of people who are participating in these, especially with the personal narratives and the kind of in the moment type of feel, the vibe that the collection has, because that’s what it is. You know something that’s happening now versus, as we talked about earlier, someone collecting and donating it at a later point. And then I think it will just kind of extend the history of the collections we have with the social action, just showing what’s happening in this time period. And hopefully you know we will, in the future, collect other collections around these types of events too. Just because we’re creating this doesn’t mean we’re going to turn down other donations that might fit really well into the collection. So it remains to be seen. But I’m hoping — at the Newberry we have a lot of scholarly researchers who are interested in it like in a historical, political, kind of sociological way but then having different artists — they are not “non-traditional,” but I’ll say “non-traditional kind of researchers” — here looking at these things as objects or from a more artistic perspective.

JPC: And then going back to the narratives, can you say a little bit more about why that was an important thing to collect as part of the archive?

CG: Yeah so when we get personal narratives, we’re always looking for context. When it comes to collections sometimes things are donated and we really don’t know history or the provenance of them. Like, “Where did this come from? Why was this created? Why it was here?” And so I think when we have that you get a stronger sense of why somebody created something, and then I think that’s another way that people are going to be interested in the collection. Hearing these very individual stories because you know when you read a news article you know they’re just bits of what somebody has said. It’s not really just like their own voice just saying it. So just giving an opportunity for people to add this to the collection, it’s pretty powerful.

JPC: Is there anything else that you’d like people to know about the archive?

CG: Yeah, I’d just like people to know that this is connected to other types of collections we have here. It’s very unique, but it is again connected to a history of collecting these types of things and we’re happy to help anybody find and research these types of topics.

The Chicago Archives + Artists Project (CA+AP) is part of Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation for American Art exploring Chicago’s art and design legacy, with presenting partner The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. The project is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Featured image: Catherine Grandgeorge holds four buttons from the Women’s March. The largest one has a picture of Trump and it says, “In Your Guts You Know He’s Nuts.” One says, “Still with Hill” and another is a campaign button for Hillary Clinton with her picture and “Hillary 2016” on it. The fourth shows actress Janet Leigh screaming in the shower scene from the movie “Psycho.” Photo by William Camargo.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Jennifer Patiño Cervantes was born on the Southwest Side of Chicago with roots in Mexico. She is a freelance writer, poet, essayist, and Director of Operations + Archives for Sixty Inches From Center. She graduated from Columbia College with a degree in Art History and double minors in Poetry and Latino/Hispanic Studies. She is currently pursuing her MLIS at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.