This interview took place as part of an initiative of the Chicago Archives + Artists Project . CA+AP serves as a laboratory and pipeline for the community preservation of artists’ archives. We want to find creative ways to care for an ever more accessible, playful, and diverse compendium of artists voices, process and ephemera. We believe in the power of stories in many voices, on many platforms, past, present and future. This interview of Roell Schmidt, conducted by Annie Morse, a curator and Senior Lecturer in Museum Education at the Art Institute of Chicago, will be contributed to Links Hall’s file at the Chicago Artist Files at Harold Washington Library.

Annie Morse: Roell, will you please introduce yourself and talk about how you came to the archives project.

Roell Schmidt: I currently am the director of Links Hall, an experimental dance group and performance space that’s been in Chicago for 38 years. And how I came to be part of this archive was: Tempestt invited me to be one of the interviewed people, and, although I am not super comfortable being the person interviewed – I’m much more comfortable promoting artists and talking about other people – I felt I could not disrespect her invitation by not saying yes.

AM: Fantastic. I’m really excited because Links Hall has played such a phenomenal role in the cultural life of Chicago, and it’s a little bit off of some people’s radar so everything that can be done to promote it and make people aware of what it does now and what it’s done in the past is going to be fascinating. And you brought materials to submit to the archive.

RS: Yes.

AM: What kind of things did you bring, and how did you decide what to choose?

RS: My career has been this seesaw between being a writer and producer of live art and film and being an administrator and producer of other people’s live art and film. It’s hard to go through stuff and figure it out, especially if you’re really shy about all of this, but what kept me going was thinking that someone might look at this who’s trying to figure that out for themselves, maybe it’s helpful to have an example of someone who’s not figured it out particularly well, but at least has not given up on either aspect of their work.

AM: The idea of promotion has a little bit of a strange aroma in our culture. I had a boss who said promotions always sounded like balloons and t-shirts. But if work isn’t promoted, then people don’t hear about it, and it’s really a necessary feature of cultural production.

RS: I also think it’s really important to have examples of people who wrestled with the same things you wrestled with. I remember when I first became interested in becoming a filmmaker, I was a French major in college and I spent my junior year of college in France and took cinema classes and made a short film while I was there. That was outside the parameter of the class but I felt really compelled. It was a highly symbolic, very, very French film. But then when I was looking for examples of other women filmmakers, I remember the thing that gave me the most confidence was actually seeing Francis Ford Coppola in the Hearts of Darkness documentary his wife made about the filming of Apocalypse Now. And in it he makes this flippant comment about how the next great filmmaker might be some girl wearing glasses from Ohio. I’m not from Ohio, but I’m definitely a girl wearing glasses, and it was one of my first times hearing that. I’m always searching out examples of anyone who doesn’t come from money, who is able to make their own art while still supporting themselves. It’s not an easy thing.

AM: By no means. And especially the more experimental you are, the more difficult it becomes to find funding or to scare up support, even in-kind support. I can imagine a lot of people end up working under the aegis of another organization rather than doing their own thing. How long have you been in Chicago?

RS: I moved here right after graduation [from Washington University in St. Louis] in 1994 because I got on a film. It was an independent feature and they were looking for free labor, so I was hired to be an art department production assistant. And I was able to work for free because my brother worked in Chicago as a consultant and had been sent for six months to another city, so he said I could have his room in his apartment because he had to pay the rent anyway. That’s how I was able to start doing that.

AM: And what an amazing way to get to know Chicago by working in production. What did you find yourself doing?

RS: The film shot all over Chicago. We were in Glencoe, Elmhurst, on the Southside, downtown, on the Northside, Rogers Park. We were all over and I didn’t have a car so I got to know Chicago via public transportation and Metra and traipsing through the suburbs from the Metra stop to get where you were going. It was actually fantastic and it was so exciting to me to be able to work on a feature and get to be behind the scenes of it and see how everything was put together. So I worked on independent films, mostly independent features, for three years and I temped in between. In the mid to late nineties was when the commercial film industry dropped out in Chicago because it became much more cost effective to go to Toronto and pretend it’s Chicago than to actually shoot here.

AM: I remember those days!

RS: So I did have this moment where I went to New York and worked in the independent feature film market there as an intern, and I went to LA to visit – it’s just people you had met because that’s how you got on the next film because you’re working crazy hours and that’s how you get the next job. I looked at LA, and I had also been working in theatre the whole time, and I was between temping and film jobs, so I decided to stay in Chicago and do theatre because I had the same love for theatre that I had for film.

AM: This is an amazing town for diversity of action, whether it is start-ups or people saying, “Come on, kids, let’s do a show,” or longtime theatrical and film entities reinventing themselves. And since the institution of Cinespace [Film Studios] and with all of the tax breaks that were enacted to coax those people back from Toronto, it’s been very lively here. You’ve balanced the commercial and the experimental, the theatrical, the filmic, very gracefully just by doing it all. Where did Links Hall come into your career trajectory and what was your first engagement with it?

RS: Actually my first engagement with Links was after the film industry sort of evaporated for a time, I ended up accepting a full time job at a place where I temped which was a commercial, corporate PR agency. I did it because I wanted to learn what stealth advertising was all about since I was also working at the Athenaeum Theatre, and Performing Arts Chicago was bringing in Robert Lepage, and Steven Berkoff, and Ballet Theatre of St. Petersburg, and all this work that transformed what I thought theatre could be. I loved theatre but I’d never seen work like this. I got to see every performance and got to see this beautiful theatre that had fifty people in it but could accommodate nine hundred. And I was just like, “This is not okay.”

I took on a lot of pro bono arts clients while I was working at Ogilvy [Public Relations] and one of them was Jan Erkert & Dancers. Jan Erkert’s home base for her company was Links Hall, and that’s where they rehearsed, that’s where they did workshop showings. So it was their 20th anniversary season and they asked if I could be their pro bono PR for it. I did that and that was the first time I was ever at Links Hall.

AM: And that was in Links Hall in Wrigleyville. Can you tell me a little bit about that building?

RS: For sure. It was built in 1914 by Dr. Link, who was a dentist. The first floor was bars and commercial spaces and the second floor – the perimeter of it was lined with the windows – was all professional offices meant for accountants, lawyers, that kind of thing. But in the center of the space there was an East Hall and a West Hall. The East Hall became Chicago Women’s Health Center before Links moved in. The West Hall was the space of this choreographer and dancer named Jim Self; he had been involved with the founding of MoMing, which was an amazingly important experimental dance space in Chicago, and while he was there he got a choreographer grant from the NEA for $2500. He then separated from MoMing, which was in some ways his administrative job, to rent the West Hall in Links Hall as his rehearsal space to make work. So he actually did his first showing, performance, who knows what else was happening there. After he moved to New York to be in Cunningham Company with Merce Cunningham. Then these three experimental choreographers, Bob Eisin, Carol Bobrow, and Charlie Vernon, took over the lease and it became Links Hall. They incorporated a year later, and then they became a nonprofit in ‘82. This is all in ‘78 that they started this. They wanted it just as studio space to pursue what they wanted to do but then very quickly artists don’t just want to rehearse, they want to perform, and it became a performance space as well.

I brought in the letter that I actually wrote that I found saying that I would like to work as an intern with The Prodigy, the feature film that brought me to Chicago. And the crew list because I thought it would be good for everybody who was part of that to be part of an archive. I think the film I was most excited about, the most artistic film that I worked on and where I discovered, it’s like “You’re naive, you’re innocent, oh you’re working on films and these are all artistic projects.” No, honestly it was a lot of: “I want to make a film that looks like a film that was already successful so I can get attention and get distribution and get money to make more films.” Zeinabu Davis created this film called Compensation that ended up screening on the Sundance Channel. It was the widest distribution of any of the films I got to work on. Just for a couple of days I was a costume coordinator on re-shoots. It was this brilliant black and white film about death, an African-American couple that was sent backwards in time and forwards in time. It was this beautiful artistic project and that was phenomenal. So I have the crew deal memo and the location contact info for everyone who was working on it. I thought that would be nice to have in here too.

AM: That is wonderful.

RS: For Lookingglass Theatre, I have the book that we created for Looking back, looking forward, Lookingglass. It was for the opening of the new theatre. I remember after, I had been working there since ‘99 and we opened the new theatre in 2003. It was an intense time. I ended up getting myself in the hospital twice because I was so stressed out I couldn’t stop throwing up. I have a tendency to throw myself completely and take on more responsibility than perhaps I should. The result was that we were getting ready to open for Race, which was Studs Terkel’s book that David Schwimmer adapted for the first show at the new theatre. I remember sitting in the back balcony in the space. It was all set up, the set was there, it was before any of the public were coming in for the first preview. I sat there and just cried. Happy tears of all this work actually coming true and all the art that could happen there.

AM: It’s worth mentioning that it was a brilliant idea to put a theatre into the pumping station of the extant Chicago Water Works, which is opposite the historic water tower, and is a building that survived the fire of 1871. It’s a Chicago landmark that has been dwarfed by all the skyscrapers around it. Many people visit the water tower but don’t notice the companion building across the street, which is where Lookingglass is lodged. A really interesting space that someone had to have the chutzpah to imagine it could be transformed into a theatre.

RS: The imaginer with chutzpah was Lois Weisberg, who was the Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs for the city. It had been this kind of tourist show that had been mothballed, and then it became this space. It really needed to have a company like Lookingglass that was able to raise the money because even though Lookingglass has a one dollar per year lease with the city; it ended up being an $8.5 million campaign when it was over.

AM: You’ve got a great picture of it. A postcard of the building itself, which is this glowing – is it limestone?

RS: I think so, yes. So Lookingglass: I was their Marketing Director and then I was their Development Director, and then the last three years I was there I was their Director of Artistic Administration. It was primarily a position created because, at that time, all the work that was created on those stages originated within the ensemble. There was this sudden real sense of nervousness, not that they didn’t have ideas, but that suddenly the work was going to be premiering on Michigan Avenue, and they had to ensure that the process was such that everybody felt ready for an audience. When the company is dedicated to world premieres, always, and the primary question they would always ask was: “why does this story need to be told?” That was really what I did for my last two years there because having worked and been in the trenches so much with the ensemble on all of this, we were really close and they trusted that everything was going to work out. What was beautiful about that time was I got to really help shepherd the development process of a number of plays, including Lookingglass Alice, which has become a major staple.

AM: Right. Much associated with Chicago and with Lookingglass as a show that people want to see over and over again.

RS: Yes. It is really brilliant. There was a major supporter of theatre in Chicago as well as Lookingglass, her name was Hope Abelson. In fact, the theatre at Court Theatre is named after her and her husband. Her eyesight was really getting poor but she lived very close to the Water Tower Water Works. One day, because she had been so essential to the success of the company and so invested in the Lookingglass artists – in fact, she was one of the first donors that the company had ever had – David Catlin, the writer and director, and I went over to visit her in her apartment to bring the mockup of the set design and do a reading of the script with her. This was not about raising more money from Hope, this was so that she could still feel connected to the company while she was feeling her eyesight fade. That was really special.

I brought in this brochure – it’s from after I left. I left Lookingglass in 2005 because the thing I knew was that I could never say no to Lookingglass, to whatever they would ask of me. I had been a secret writer the entire time I had been working there, and not secret because I was ashamed but secret because I was shy. I left to go to the Chicago Chamber Musicians where I was able to negotiate only working four days a week except for concerts. I was able to spend Friday through Sunday on my own writing. Lookingglass did reach out, and of course I didn’t say no, in this transition period after I left so that I could help consult on their subscription season and helping to get the word out. I was able to help create a brochure and do the writing for it and pull the photos and all of that. It was a wonderful season, and it was really successful in terms of really increasing their subscriber base, which made them feel like, “Okay we have the space, we have the art, we have the audience.” That was a beautiful way to conclude my time on staff or as a consultant for them.

RS: While I was at Chicago Chamber Musicians, I went to the One State conference that Arts Alliance Illinois would throw every year. At Lookingglass, I didn’t really engage in a lot of stuff with my peers and community because I was so busy. Once I was at CCM, which was the most tranquil organization I ever walked into that was a nonprofit arts organization, it was calm all the time. They had this huge reserve so they weren’t worried about money. Their ensemble were all professors or members of the CSO so this was their artistic outlet, not a financial necessity. It was much less stress.

AM: That must have been a relief.

RS: It was. I definitely took on less responsibility because there was less responsibility there to take on, which was very healthy for me. While I was at the One State conference, I met Byron Johns, who was then the executive director of Deeply Rooted Dance Theatre. He was a secret artist himself. He was a musician who had written a number of songs and was still writing songs. I was a secret playwright who had been working on this “cineplay,” which was a feature film embedded in a play, for years. He and I committed to each other at that conference that we were going to support each other in achieving these secret artist yearnings. Together we actually co-produced a workshop that was his work and the first act of my play at Chicago Cultural Center. The following year, we created an “Artists as Managers, Managers as Artists” panel for the One State conference at Urbana because we felt we couldn’t be alone in this. It was a really good conversation; we discovered a lot of other administrators and artists who felt that one or the other was getting the better of them.

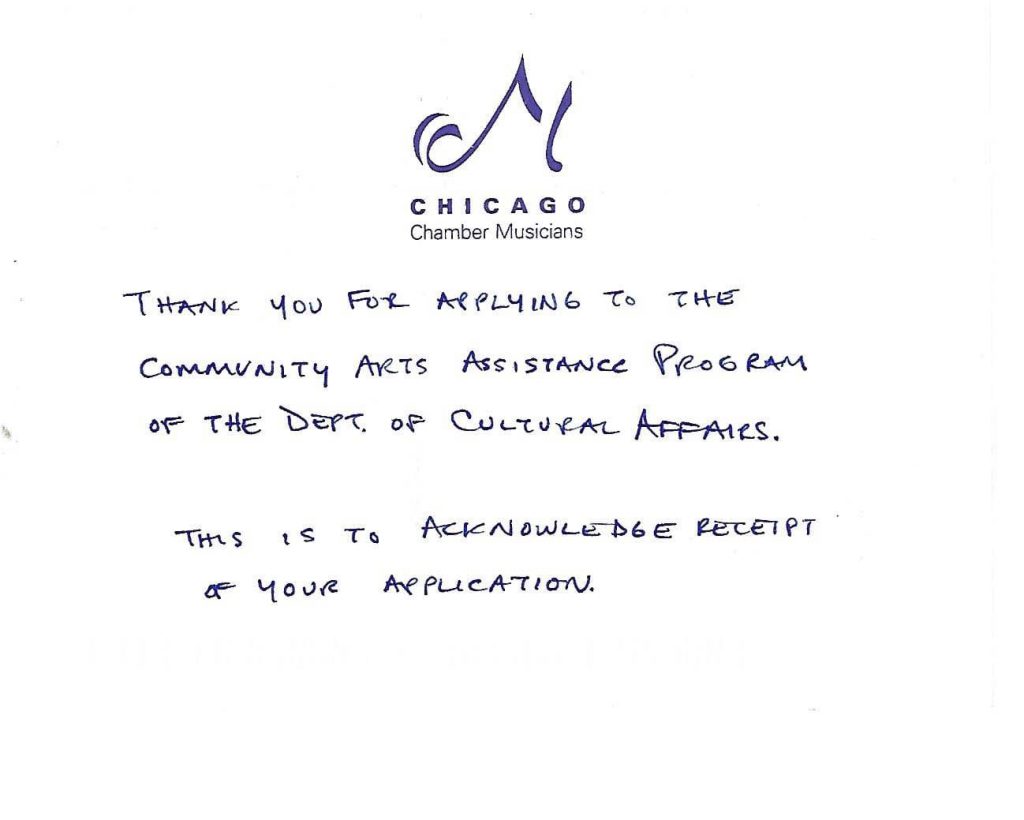

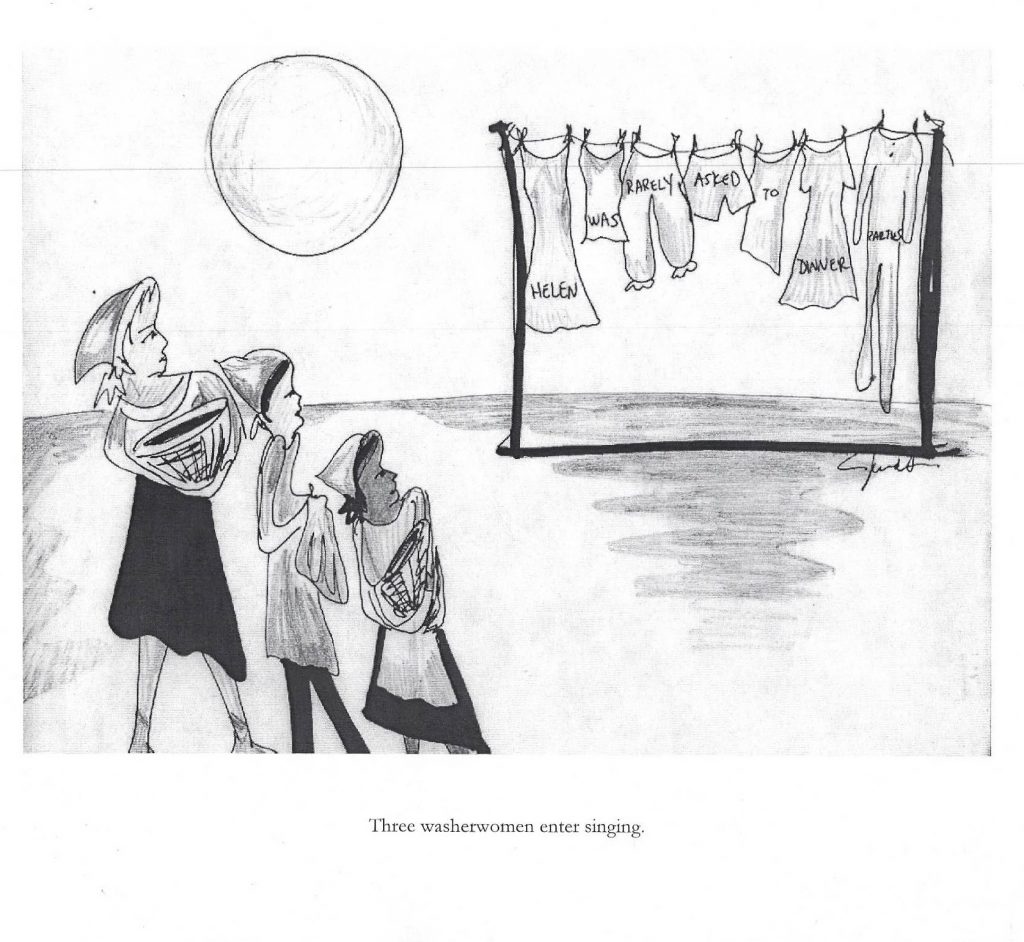

At the same time I was working on applying for the grants for individual artists that the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events used to have. I got one and it was $500 or something, and I remember getting that grant and thinking, “Strangers think I’m an artist!” It was incredibly validating and important for someone like me who always feels selfish about doing her own work, so when someone else is asking you to do work, be it a grant or residency, it pays off far beyond that $500. What I was able to do: because of this crazy big script I was doing, it was hard for people to visualize because it was half a stage play and half a screenplay, and everything had to be really coordinated because we kept changing the projection surfaces. It was clotheslines – it was different surfaces throughout the play that kept being manipulated. What I have here is a little – at that time, DCASE would ask you to send this postcard in that said “Thank you for applying to the program. This is to acknowledge that we received your application” but you had to write it out yourself. Then they would drop it in the mail when they got your huge application – it used to be like twelve copies of everything. It’s on a Chicago Chamber Musicians notecard that I had sent in very late one night after hours. I got that grant and I was able to hire an illustrator to help draw what was going on in my head in particular moments of the play, what’s going on onstage and what’s going on onscreen and how did this all work.

AM: There are some really interesting stage directions here: “Sir James stalks forward in a knight’s medieval garb, a falcon on his arm.” How are you going to pull off that falcon?

RS: We have a stuffed falcon. [The cineplay] was very autobiographical, although not directly. To me, the film was the real life of the characters, and the stage was their fantasy selves, the selves that real life was supposed to be. But the film life, the projected life, was not coinciding with that. The secret writer was trying to come out of her secrecy, and that was definitely a lot of what was going on in the show.

AM: Yeah. And who did the illustrations?

RS: Janet Arvia did the illustrations for me. There’s just a bunch of illustrations that she created that I embedded in the script, and Lookingglass asked to do a reading of it and everyone found it incomprehensible.

AM: Aw.

RS: It was fine! It was fine.

AM: So you heard actors reading it.

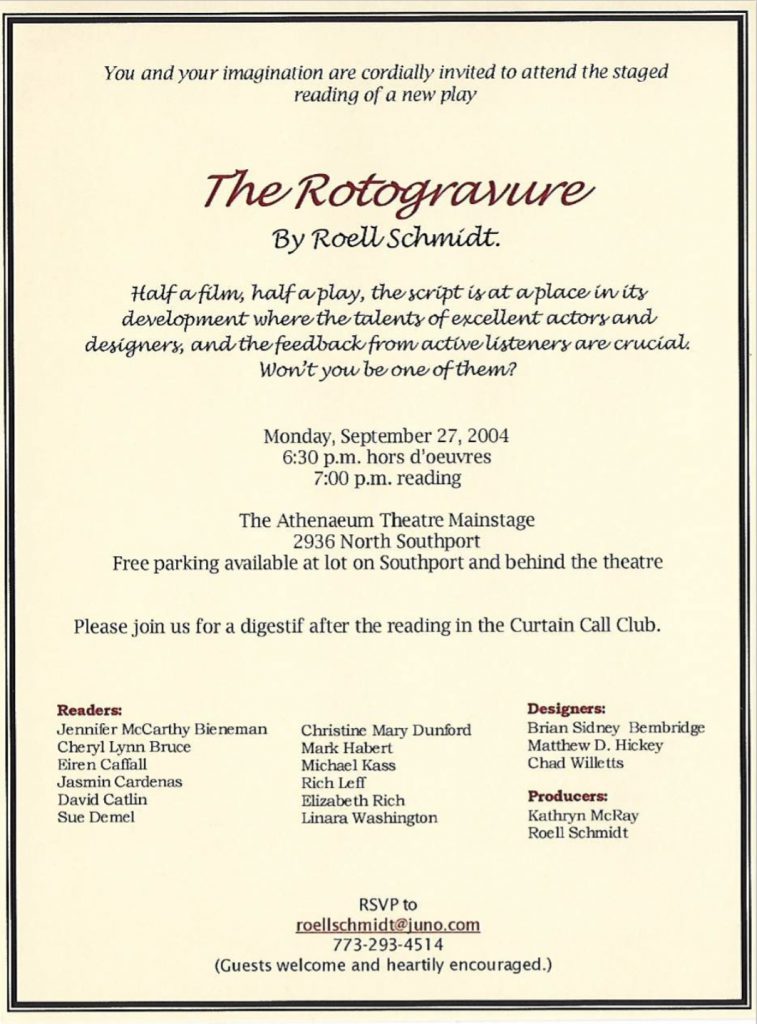

RS: I heard actors read it. What I learned was that in order for people to understand what I was doing, I needed to get it on screen. At that time, my great aunt Cele Schaller who grew up in Joliet, Illinois where my mom’s side of the family is from, died in 2002. She left me $2000 in her will, so I used that $2000 to take the script and do a staged reading of it. Thanks to my wonderful relationship with Lookingglass, I was able to cast it with a bunch of Lookingglass performers, including Cheryl Lynn Bruce, who is amazing Chicago theatre royalty, David Catlin, and Christine Mary Dunford, who are also a members of the Lookingglass ensemble. We did it in 2004 on the main stage of the Athenaeum, which I was able to get since I worked there and pulled in a favor. We did a staged reading of it, and we even shot some of the opening so that people could get a sense of how the film and the stage action worked. I have the invitation that I created for that.

AM: And the title of the work?

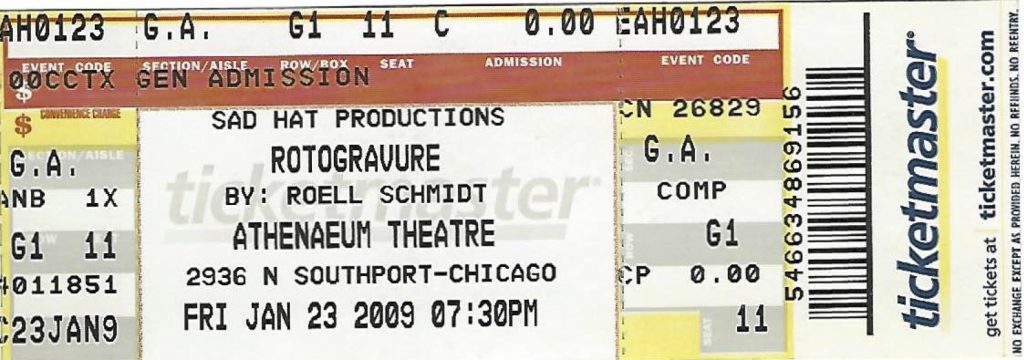

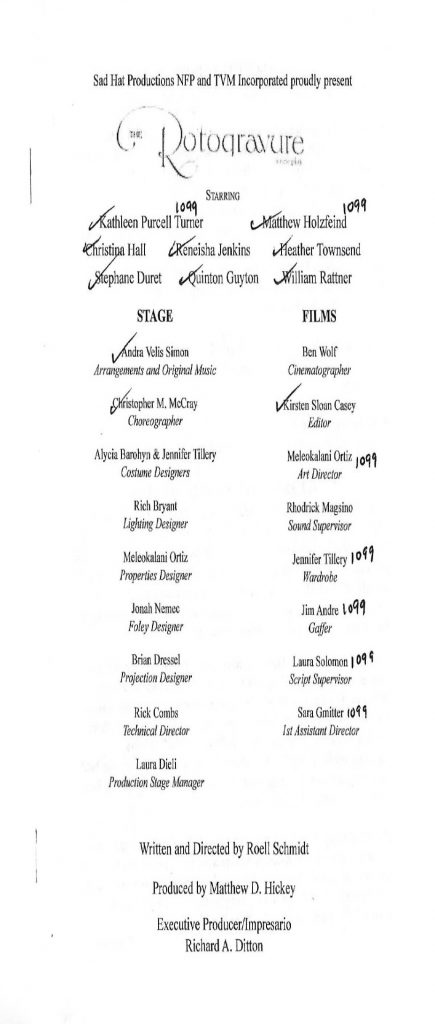

RS: The title of the work is The Rotogravure. I first came across that word in Easter Parade, the musical, because the song’s about the Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue: “The photographers will snap us and you’ll find that you’re / in the rotogravure.” I looked it up because I didn’t know what it was. In newspapers, for a good chunk of the early part of the 20th century, the rotogravure was the full color pictorial section of the newspaper. That’s where art and architecture and fashion – where the larger than life happened between the black and white daily news. That seemed perfect for what I was attempting. I have the program from the staged reading and that was this moment when…that was my coming out party, I think. As somebody who is no longer a secret artist but an actual one. I woke up that morning full of so much joy and excitement. Every show that happens is a miracle that it happens at all, and everything that can go wrong does, but it was great. It was joy. It felt wonderful and enough people understood what I was attempting that it felt like I could keep going.

AM: What was the date of that?

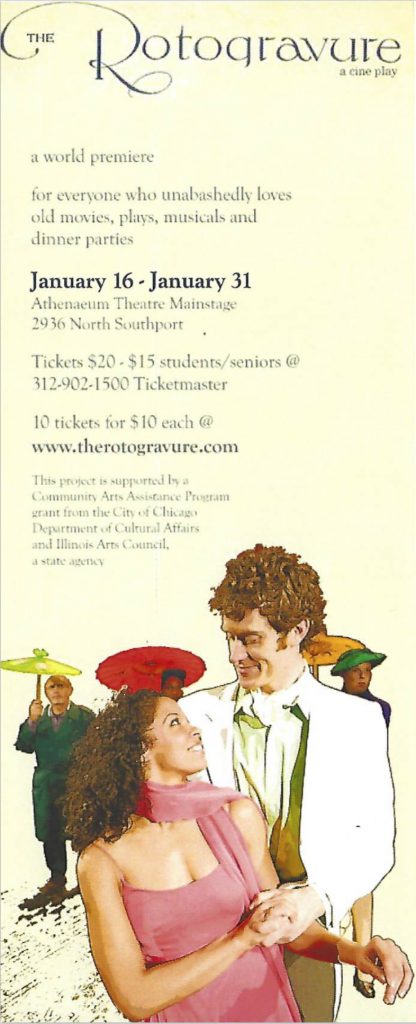

RS: The date was Monday, September 27th, 2004. That was right before I left Lookingglass to go to CCM. That was before I got the illustrations and everything so the script could have a better chance of being understood. I did have a couple theatre companies ask for the script so they could read it but everybody was daunted by how large it seemed. So I took it on myself, which was insane, and a huge amount of work. We shot the feature film in August, 2008. Then we had the full production January, 2009.

AM: Where was that?

RS: It was at the Athenaeum Theatre, and it ran for three weeks. We had a thousand people come see it. Part of the good thing about mastering the art of art administration before you produce your own work is you learn how to do things, and one of the things you learn how to do is to develop an audience. I asked friends of mine to host dinner parties. The play begins on the projected surfaces of this clothesline, and on the clothes it says, “Helen was rarely asked to dinner parties.” Helen thinks that real life will start when she finally gets to go to a dinner party, which she’s imagined based on old films. I had 13 people, some of whom I knew at the start of the process, but the year leading up to the opening, every month there was a dinner party held by someone and then people would come to the dinner party and really enjoyed it and had their own. I would come to the party and tell them about the process and people would use the dinners to talk about first loves, or crushes, or real life versus fantasy life. The themes of the show that ended up making for wonderful dinners. Most everybody that came to those dinners came to the show.

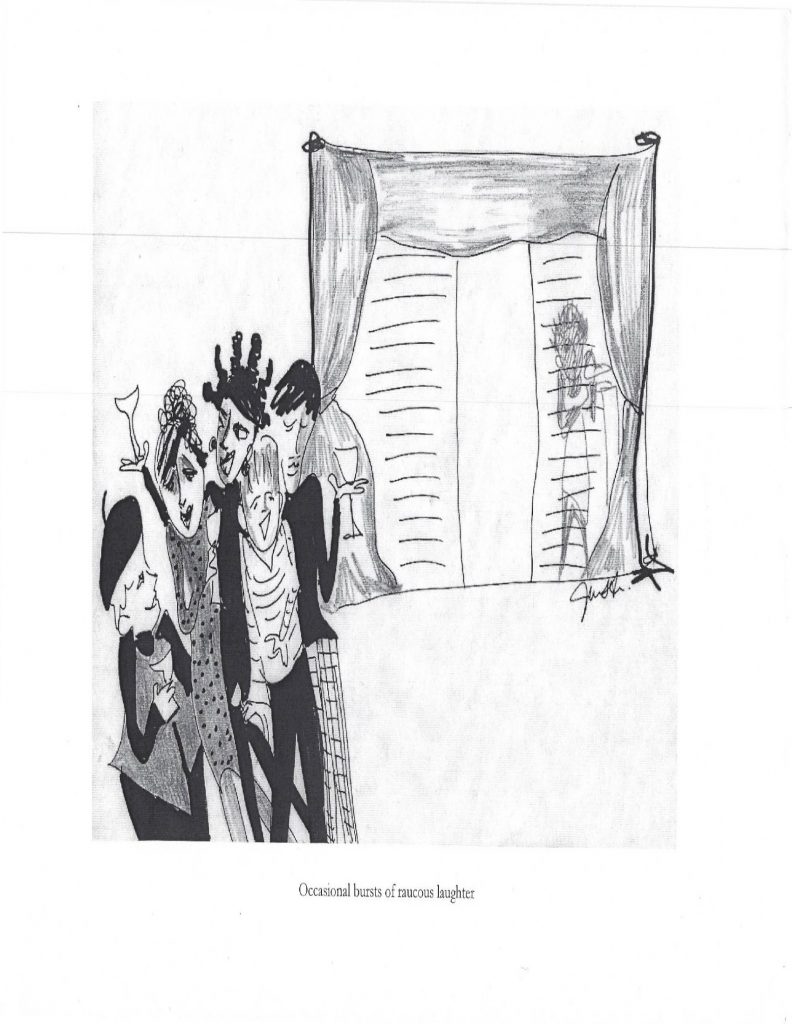

AM: That’s amazing. I’m looking at the flyer here that has an image showing a couple that are looking very amorously at one another. Are those depictions of the central characters?

RS: That’s Helen and James, yeah. I have the program from the show – I couldn’t find any that were clean. I think what’s most important to me is I had a website where I talked about the long, long, process of creating this work and this is really going through and thanking everyone, the years of “everyones,” who helped make all this happen. Then there’s a ticket stub because I used to save ticket stubs of everything I ever saw because of the The Glass Menagerie when Tom comes home and out of his pockets he’s trying to find his keys and this shower of ticket stubs comes out because of all the hours he’s spent at the movies. For years I would save them, so I saved my own ticket stub. I also have this screen poster that was created by Screwball Press, Steve Walters, for The Rotogravure and it has all the signatures of everyone who was involved in the project and they all wrote little notes. I felt this was gathering dust and all these amazing artists and collaborators could be preserved.

AM: The face peeking out over the title of the work is a great graphic device.

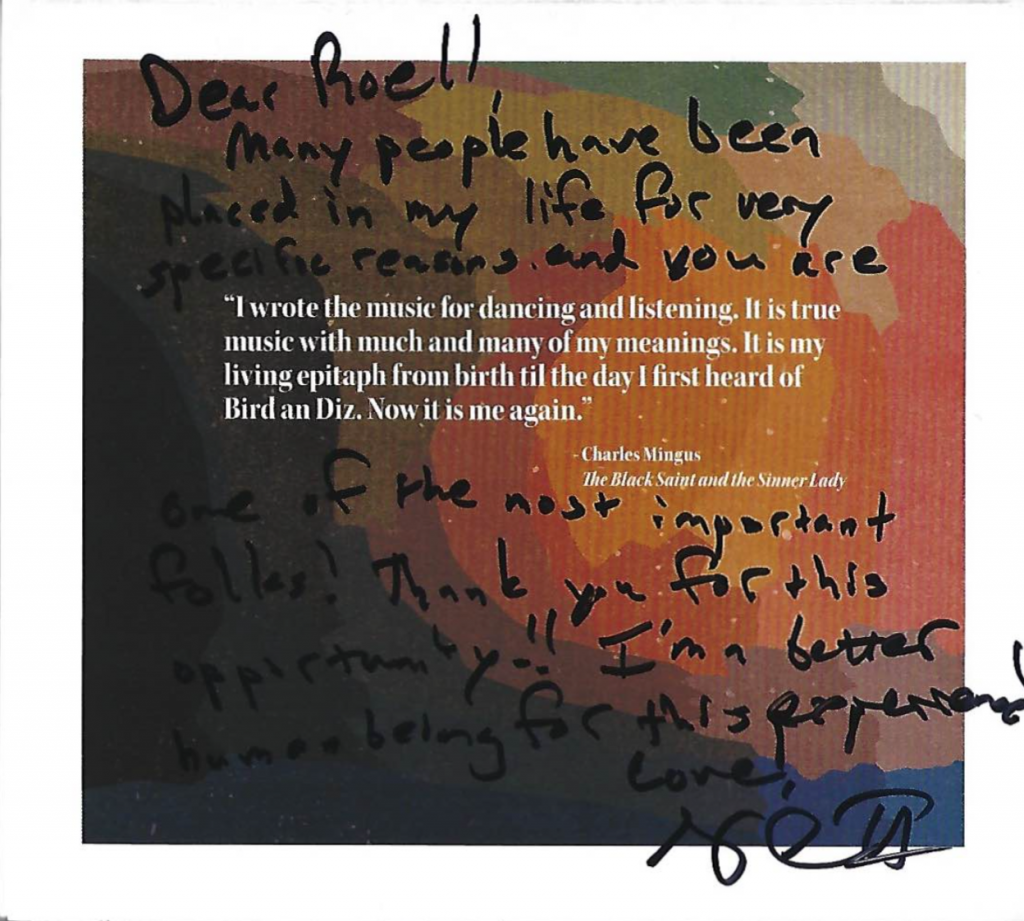

RS: That was Roto. There was an eight person cast – one was Milton, the grandfather. I had met Bill Ratner, who was executive director for Lawyers for the Creative Arts when I was forming Sad Hat Productions to incorporate it as a nonprofit in order to be able to do the show. He was so delightful and such a standup performer, even though he was a lawyer and an executive director, that I reached out to him afterwards and asked him to come to a reading, and he ended up being Milton. He wrote this really lovely letter following the premiere of the show in 2009, and it was the same thing. It was somebody who was working in the arts while having a real yearning to be creative. It was his first acting gig, and he’s since asked me to write another part for him which I have not yet done but maybe someday.

AM: That’s a wonderful testimony to both of you being creative thinkers – that he was willing to take it on and that you were insightful enough to offer it to him.

RS: That’s the thing. We can’t keep segregating people and thinking that people who work in the support or the producing of art don’t also have stories and things to say. And we can’t also think that artists aren’t capable of the producing side of things. The way presenting has gone, if you aren’t self-presenting you aren’t going to get any opportunities. The next moment, right before the Roto production really took off, I had applied to Ragdale, which is an artists residency in Lake Forest, and I had applied and gotten the most wonderful rejection letter ever. When you don’t have enough time to focus on your artistic practice, the yeses are much more potent and so are the nos. This is them saying, “The panel really liked what you had to say. We’d like to put you on the waitlist, but we don’t have a slot for you right now.” I was over the moon. I was on the waitlist! It was not a no! It was like getting that first grant for the city. Within nine months of that, I received a call from Ragdale saying that an artist who was supposed to have a residency had to truncate theirs, so if I wanted to go I could have two weeks there. I went and I have here the list of residents from when I got to be there. They gave me the playroom because I’m a playwright. What was so wonderful about this is one of the other artists that you were interviewing today is Rhonda Wheatley, and she was there when I was there.

AM: Oh, wonderful.

RS: She’s a visual artist and also a writer. Although when she was working there it was primarily in visual art.

AM: I want to take a look at this because I also went to Ragdale. It was so transformative and such a wonderful experience that we ought to underwrite.

RS: It was great group. When you first arrive at Ragdale there’s a sign that says “Quiet Please, Artists at Work” and to see publicly what I had been feeling secretly was incredibly validating, and healthier for me to not be so divorced. One of the writers who was there was Justin Quarry, and he and I got to know each other during the course of the two weeks, and actually he sent me the work that he had written at Ragdale – it got published in the New England Review – and he named one of the character’s last names Roell. He sent me a card about how much he enjoyed meeting me and was inspired by me enough to – although it’s a terrible character, I thought it was hilarious and wonderful– but it shows for me, in my trajectory, that there’s actually as much joy in other artists making as in my own making. There’s probably more because I don’t have to deal with feeling selfish when supporting others. I ended up going to Links Hall and becoming the director there in 2009, the summer after Roto happened. It became all-consuming because I had walked into another imperiled organization. It was right after the downturn in the economy and it took a little bit for nonprofits to immediately feel it. They were certainly feeling it at Links Hall in 2009, and I had to lay off the staff almost as soon as I got there. It was also when Links was celebrating its 30th anniversary, so it was trying to mark that while knowing that things are in shambles. It was a time when a lot of funders in Chicago who had been longtime arts funders decided to cease funding the arts. It was a really perilous time, and we were able to turn it around and keep it going.

AM: How did you go about it – reducing staff and reaching out to new funding sources?

RS: Primarily my answer to this was: it’s about saying yes to art. If Links was not a place where artists wanted to make work, there’s no reason to keep it alive. When I arrived there were swathes of empty weekends with no artists making work. A lot of that was the fact that artists were freaked out and financially crippled by the economy and the downturn. The thing that’s great about Links is that when artists are hurt we feel it immediately. There’s really no insulation so you have to respond immediately and change course. What I ended up doing is a lot of talking with artists and finding out who had something that they were ready to share but couldn’t afford to take on the rental, and listening and saying, “actually the themes you’re working in are very similar to this other artist,” to create these shared bills of artists so they could still have performance opportunities, and changing the structure so that instead of a flat rental rate it was a door split among all four of us.

AM: So you were curating evenings of performance from individuals who might not have been able to pull off a short piece alone so that they could be seen with others.

RS: Exactly. If there is one theme in my career, it has been partnerships, it has been collaboration. That’s why I’m interested in live art, because it’s a collaborative creative process. Writing for me is solitary and challenging. I’m definitely a person who likes to be on her own, except the joy to be found is with others in collaboration, everybody working together to make something. The biggest thing that turned Links around at that time was Links had been doing this “friend-raiser” because apparently, it was hard for me to believe, but Links’s audience was aging. I come from Chamber Music where the average age was 68, so I was like, “this is aging?” But what was happening is it was becoming more of a club for a certain group of artists and their friends or peers, and that was aging. It was really essential to me to change that, and they had already started this party called THAW to bring in younger artists, younger people. But it was a party and not a fundraiser. I said no, it has to be a fundraiser. We got Boeing to support it by pairing with Seth Bockley, who is a wonderful theatre maker and artist. He had knocked on a bunch of doors wanting to do a toy theatre puppet festival in Chicago. He wanted to bring great small works from New York in. Everywhere he knocked, everyone said no.

Then he knocked on my door and I said, “You know what, Boeing likes puppets. I bet I can get Boeing to support it. And if we get that money and tie it to the THAW fundraiser, then we can afford to do this.” [Seth] is amazing, and he’s actually been collaborating with Bob Falls on works at the Goodman [Theatre] and he’s gone stratospheric, but at the time he was knocking on doors wanting to do this toy theatre festival, which is basically two-dimensional tabletop performances. It was particularly appealing to me because I had this showboat, a plastic showboat as a kid that was for toy theatre. It has sets and scripts and little paper characters that you could perform in your living room, so actually I had performed toy theatre before. We did that and it sold out. It really helped audiences realize that Links was still there. The other thing that was super important about that season is the artistic associate festivals where we invited artists to apply to curate festivals. They were in improvisational dance and music, in cantastoria, which is a different form of visual art with dance and storytelling, and these things were really helpful in keeping it artistically relevant while we were fixing the administrative structure.

AM: Those balls in the air, keeping a laser-like focus on the fundraising while you are producing the work – even if the production is handed off nominally to a third party, you’re still intimately involved with every step of that.

RS: What also helped was that Steve Walters was a personal friend of mine, so we had this performance art festival called Dirt that was curated by Deke Weaver from the University of Illinois. Deke had ideas about what he wanted it to look like but I asked Steve to do the design. Then we put up these beautiful silkscreen posters near the Art Institute, and I remember hearing from the Art Institute, “Oh, it looks like Links has a new lease on life,” because we were suddenly looking artistic. Because one of the things that art funders have liked to do since I’ve gotten into this game is to decide that arts organizations need to be more corporate. I’ve worked in corporate, and no, arts organizations need to be treating themselves as artistic incubators and spaces for artists to do creative thinking, not modeling after a corporate model that has been proven to not be so healthy either. Links had moved in the direction of these glossy brochures that did not look at all like this very small, cramped studio, and did not look at all like what was happening. Getting those things in line was really important.

AM: It’s very interesting, the visual tone that signals what this is, that says, “this is reliable, safe, and has qualities of a Lyric Opera or a Goodman Theatre,” as opposed to, “this is edgy, this is new, this is something that is the brainchild of one person rather than many.” All those choices are really hard because they can be pulled in so many different ways. Having come out of theatre, and music, and film, and production, and writing, it seems like you’re perfectly equipped to evaluate that. Who produced the silkscreen posters?

RS: Steve Walters from Screwball Press.

AM: From Screwball Press, and he also did the poster for the play. And Deke Weaver from UIC?

RS: Yes. What that season really helped do is show that performance art is welcome at Links Hall. Cantastoria puppetry is welcome at Links Hall. Improvisational dance, which is the sore spot from which Links got its start, is welcome at Links Hall. All of those things are what make Links. The other piece is that everything that happens at Links Hall, and everything that happens in art, is personal, but it’s particularly personal at Links. These are artists who are either doing their first thing ever, or they’re artists who have been making work for a long time but are taking a risk to do something different. That’s what Links embraces and that’s what makes it so close to me.

I realized after working for two artistic ensembles that are really about preserving the ensemble and about an exclusive approach to artmaking, which is totally understandable, that you need people to help put it together and when you have this reliable group, you hold on to them. For me, I have a much more inherently populist attitude where everyone has the right and should have the opportunity to share their personal story at whatever stage they are and wherever they’re learning. That’s why being at an incubator really feels healthy. However, as anyone who is trying to balance their artistic practice with an administrative one knows, it’s really difficult to make your own work a priority.

What I ended up doing after the momentum of The Rotogravure was that I was asked to submit a short play to 20% Theatre’s Snapshots Festival. It was called Pixie Sticks, which had a string quartet embedded in a play – I like to keep things embedded in one another. I also did a dramatic documentary script about the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago and that got a staged reading. It all happened in 2009 and it was a very intense year. Then, with all the peril Links was in, I really had to take a step back from my own work. I decided to apply for a writing program because I was doing so much producing that I wasn’t going to have time for directing and all of that work, but I wanted to keep feeding the writing. That’s what I needed with 20% asking me to write a play. I needed someone to ask me to write. I applied to the Art Institute with their Writing MFA because I needed something larger than me asking me to write. I was accepted which was one of those moments where I was like, “really? Is it hard to get in here?” Honestly that was my question, and it wasn’t until the orientation that they said how many applications they got and how many people they accepted that I realized, “oh, it is hard to get in here.” I ended up going on a very slow part-time boat through SAIC. I started it in 2010 and I completed it in 2015. I have the journal that they create for the outgoing MFA writers. And something I wrote in Jesse Ball’s lucid dreaming class.

One of the things that’s also really important to my story that will hopefully reassure others was that I lost both of my parents during my career. In 2002, my mom died of ovarian cancer, and it was within nine months of opening the new theatre in the Water Tower Water Works, so it’s not surprising that I was so stressed out – I was in the hospital. Then, 2012 was when my father died and he had a much longer – he got sick in 2010, and it was actually the third week into the semester when I had to go down to St. Louis and my dad was in the ICU, and it was three years later that he died.

That was six months before opening Constellation / Links Hall, moving Links Hall from its longtime space into partnership with Mike Reed. Mike is a composer, percussionist, presenter, impresario, he’s everything. He and I were both asked to be on the cultural advisory council for the City of Chicago when Michelle Boone came in as the commissioner because they wanted to do a new cultural plan for the city. Again, I was asked and I was like, “how did I get on this?” I always get a little taken aback, like when Tempestt asked me to do this. I’m always a little bit taken aback by it. Mike and I met on the first day and we really hit it off. He asked me what’s with Links, and of course I told everyone I ever met that we were looking for a new space. We looked at 150+ spaces and we were also raising money to be able to afford the buildout because we knew we couldn’t afford to buy the building. We needed sprung wood dance floors because 50% of what we do is dance. We kept seeing spaces that had columns or spaces that were great but we couldn’t afford the renovations for more than a floor. I remember saying jokingly, “we just need someone to want to buy a building for us.”

What happened was I was in Minneapolis on the McKnight Foundation’s choreographer’s panel to choose their choreographer fellows, and I got a call from Mike Reed. He said, “Roell, can you send me the specs of what you’re looking for for this new space for Links?” and I said, “Sure, but I’m out of town right now.” He said, “because this building that I’ve always wanted to own might be coming sale. It’s not public, and the only way I could do it is if I had a partner like Links involved in it. Are you in?” I said, “I need to know what the building is first.” He said, “I can’t tell you that.” I was like, “Well, I can send you the specs and you can tell me about them, then we can start the conversation.” So I did and it ended up being the Viaduct Theatre. We entered into the partnership and it was very difficult because I had to be very circumspect about telling the space committee and the board that this was even an option since the owners were going back and forth about whether they even wanted to sell it. I knew that if our board and space committee saw this space, everything else would look terrible to them because it was so perfect.

It was two studios, there was room for offices, there was a bar, it was one floor so it was finally accessible to people who can’t do stairs. It was in a space that had already been established since 1997 as a performance space so people had already blazed their trail to it. Everything about it was ideal, and if it had fallen through, nothing else would have been as good. We ended up finally getting the owners to agree and then began trying to close on it. I got everybody to look at it, everybody loved it, and we gave three month’s notice to our landlords at the Links Hall building. The goal was that we would be dark in January so that we could move, and we’d get everything ready and start having shows in February. The closing didn’t happen until March, however, and we had to be out by March 31st. We basically couldn’t afford to have full-on professionals do all the demolition, we could only afford to do the renovations. The entire Links Hall staff and a core of amazing volunteers from the Contact Jam and everyone else came out, including my husband and all of his friends, and we just took apart the old Viaduct to get it ready for the professionals to come in and make it the new Links Hall.

The very first show we did was April 1st, 2013. It was up to the very last minute before we were able to clear out enough space that we could have an audience and artist. We performed with work lights, but it was fantastic. It was called Fraction, a work-in-progress show, and it was with teen dancers because the choreographer taught at a school. It was a professional choreographer who wanted to show her work – it was a beautiful, amazing night. We ended up working in a construction zone, the artists and Links staff and everyone else, for about nine months. Then we re-entered into a construction zone when we got a grant from the City of Chicago for small business improvement fund to do the rest of the work. It was a couple of years of working in construction, and I have to say thank you to all the artists and audience members who put up with that. It was not easy.

AM: But you had the support because people were so thrilled to know that this was going to go forward. It wasn’t going to get pulled, it was going to develop and grow in a partnership.

RS: Absolutely.

AM: And the cross-fertilization of audiences has also got to be productive.

RS: Working with Mike, and working with Constellation and Links – Mike presents music and Constellation is a for-profit music presenter, so how the building actually functions is that Constellation owns the building and Links is a tenant. The rent we pay to Constellation covers the mortgage, but all the other expenses of the building – the toilet paper, the lights, the heating and air conditioning – all has to be paid for by the bar, which Constellation runs. We manage the space during the day in terms of both studios being available to artists for rehearsals or residencies, then in the evenings it’s a Constellation show in one studio and a Links show in the other. There is a misconception that one studio is Links and the other is Constellation, it’s actually both/and. More often than not, Links is in the white box because it’s a smaller, more intimate space, and the work that we’re working with artists on and co-presenting on needs a smaller space. The larger space has the more robust, crazy sound system and the larger bands need that sound system. It really just depends on the work. That’s how it works.

Links, of course, is a nonprofit, and we’ve begun being programmatic partners as well as building and space partners because Mike had brought in the Instant Composers Pool from the Netherlands in April, 2013. That was a really big deal for him because as a young musician he had felt really embraced and supported by these artists from the Netherlands, and he is of Dutch ancestry as well, so there’s really a lot of roots there. He wanted to be able to, in his own home, invite these artists and present them to Chicago. They do a lot of work with dancers so we were able to pair improvising Chicago-based dancers with these amazing improvising musicians from the Netherlands, and it was thrilling.

That was the first thing we did together. Other things we could collaborate on, but then one day – I have to mention my husband, Matthew Hickey, whom I met on the first film that I worked on where he was the art director. He’s been integral to everything that I’ve done. A friend had given him Charles Mingus’ Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, the album from ‘63. I just happened to be listening to it one day, and having been from chamber music, especially in the contemporary chamber music that we were doing, I was listening to this and thinking, “Why is this not a staple of American classic jazz chamber music?” I brought it to Mike and I was like, “Do you know this?” On the back of the album, it says how each of the tracks is paired with dances. I did research and found that Mingus had intended it to be a piece that would be danced, but it never ever achieved that. People had done sections of it but no one had ever fully realized the intentioned work. So I was like, “Mike, we need to do this.” He listened to it, and he came back to me with, “Okay, but I don’t just want to recreate what’s already there.” First of all, Mingus manipulated it so much in post that it would be impossible to actually fully realize what he created. Although, a Chicago Jazz organization actually did transcribe it and perform it within months of what we ended up doing, which was sort of amazing. It was the zeitgeist to be very focused on Mingus at the time.

So Mike was like, “I would actually like to identify someone to compose a new work inspired by it.” To which I was like, “Great. That’s even better, because I’ll bring in a choreographer who’s creating work inspired by material that’s all new.” It’s wonderful if the composer is in equally the same boat as the choreographer. Mike identified Greg Ward, who was part of this band Poodles, Places, and Things. He was from Peoria originally, lived in Chicago for a long time and went to New York, and was either making noise about coming back to Chicago or Mike really wanted him to come back to Chicago, I’m not sure which. So we thought this project would be great for Greg. Greg is an alto sax player, and the alto sax features prominently in Black Saint. Greg said yes, and then I had identified Onye Ozuzu, who had come to Chicago to be the chair of the Dance Department at Columbia College Chicago. She and I had a conversation at one point where she was like, “I feel like Chicago sees me as an administrator and not an artist.” As you can imagine, that spoke very strongly to me, and I was like, “Onye, there’s a simple way to change that. Show them you’re an artist. Come do a show at Links.”

So she did a show at Links, and she collaborated with Peggy Choi from Madison, Wisconsin. One of her pieces was this incredibly powerful dance work that was set to Coltrane, and I was like, “You’re already inspired by jazz, so what would you think of this?” I talked to her, Mike talked to Greg, we brought them together to see if there was artistic chemistry and they said yes, and we applied to the Made in Chicago: World Class Jazz series, and they said yes. This was in February of 2015 and it was going to premiere in August. Mike and I would co-produce it. Greg was based in New York and Onye was in Chicago, so she would send him files of her working with her dancers in the studio, he would send her MIDI files of how he was creating the new music, and they went back and forth and inspired each other equally throughout the entire process. That moment I described of being in the Lookingglass Theatre and crying with joy – that’s what this project was. It was everything I had learned to do in my career culminating in these amazing artists bringing this work to life and it was beyond anything that I could imagine.

The name of the piece became Touch My Beloved’s Thought. Greg was able to find a label, Green Leaf Music, to distribute and publish it, and I have the one he gave me with his note in it, because what is so amazing to me is that artists have entrusted me with helping to realize their work. He asked me to write the program note for the album.

AM: That is a really beautiful object. Is there another life for this work? Is it moving on?

RS: It premiered in Millennium Park on the Pritzker stage in August, 2017. It was the 50th anniversary of the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians] so the moment was so right for it. The AACM was started to really foster work by Black musicians in Chicago, who were very much underserved and underappreciated. Mike was actually a very young vice president of AACM so there are all these connections. Mike and I co-presented Touch at Constellation/Links Hall in June, 2016. It was beautiful to welcome the work back to where the dress rehearsal and where a lot of the creation happened. It’s just stunning. It’s an amazing work of art, and I can’t believe I got to help bring it into the world.

Collaboration is really what I think is essential. You can do more, and be more, and create more, with more. Rarely, that more is dollars, but the more that always exist in the arts is more fellow creative people, more people who are hungry for this, more people with voices who need to be heard. That feels essential.

AM: Roell, thank you so much for giving us your time, and your thoughts, and your experience. Do you want to say a brief shout out to Constellation/Links Hall, where it’s located and how people can find it?

RS: Yes. Constellation and Links Hall, we share a building. You can call it Links Hall, you can call it Constellation, but it’s the same place. That tends to be a concept that people have a hard time with but that’s fine. It’s at 3111 N Western Avenue. We are on Western Ave, just south of Belmont.

Featured Image: Roell Schmidt at the Chicago Archives + Artists Festival, May 21st, 2017. Photo by Sara Pooley.