“I hate that my life is teaching me that I can only be loved if I put my love out of reach and just drift above people until they love my remoteness.”

–Boy, Snow, Bird, Helen Oyeyemi

I could have lived off of his scent. Specifically, the stink of his armpits before he had a chance to shower. Never mind that I have no sense of smell. All I can remember is the taste—limestone chalk and table salt. He kept asking me if I could guess what deodorant he uses, and I did not want to admit I could not smell him, so I kept pressing my supple nose into the unkempt bush of hair and playfully poking him with my tongue. I listed off all the Old Spice scents that I could remember off the top of my head (I stopped wearing deodorant at the beginning of the pandemic, so I had to really concentrate to conjure a picture of the Walgreens aisle in my head): Fiji, Bearglove, Wolfthorn. Nope. Nope. Nope. He laughed and pulled back, squeezing my head in between his bicep and chest.

I write his name in the margin of Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar: Why We Went Out alongside a passage about armpits:

“I stopped wearing deodorant. [My partner], with relief, followed suit. His odor is celery and mine is pencil shavings. It was a revelation to discover that we came with an aroma we didn’t have to pay for.”1

Meaning to share it with him later, I dog-ear the page. I think about leaving an audio message of me reading it, but I am already pretty high and know there is a significant risk that I will overelaborate, describing the hours I spent reading outside on my parents’ lawn this past summer, oftentimes basking in the sun for six or seven hours at a time, only taking small breaks to let my eyes rest. I would stretch my arms above my head and get a sudden whiff of my own sweat, and I would inhale sharply through my nose. I imagine that I smelled like the juice of sour cherries just creeping past ripeness. Although, this is just a guess. I never asked him what I smelled like, and I have no sense of smell, remember?

Sometimes, I worry that reading and writing are the only way that I know who I am in relation to the world, borrowing all my words from other people instead of smithing my own, living through language rather than through my body and my experience. I think that I read so zealously in the hope that one of the books will provide a roadmap for how I should live, what else I should read, what I should care about, what I should think about the world and other people, what I should say, how I should feel and experience my emotions. How many hours did I spend strategically underlining passages of Torrey Peter’s Detransition, Baby before our first date in some sort of alchemical, metatextual attempt to flirt? I nervously hand him the book outside of the café at the end of our date, and he tells me how cute it is when I roll my eyes, which I rolled my eyes at of course. I lay in bed and imagine him reading the line, “I want a man to love me so much he murders me. I want to die because I’m loved too much for him to tolerate my existence.” I want him to imagine me as the kind of person who would unintentionally highlight that line, who would find meaning in those words, not as a blaringly unsubtle message for him, but as some profound indictment of my own masochistic orientation to desire—needing to be obliterated by love.

He never murders me. Instead, he lays his head on my bare ass and murmurs, “I could stay here forever.” But then he leaves abruptly, without explanation, and I take the wine bottle we emptied earlier out to the dumpster and lob it into the metal bin so I can hear it explode. It doesn’t make me feel better. I leave my apartment without putting on underwear or socks and walk like a fiend around Lincoln Square in an attempt to shake myself free of the weight pooling in my chest. I feel like all of my organs are deflating, pulling me towards the ground. A pair of busty MILFs, one blonde and one brunette, are standing and smoking outside of Merz Apothecary, so I cross the street and ask them, “Do y’all have a cigarette I can bum?” The blonde fishes a pack of cigarettes out of her purse and holds it out with her beautifully manicured hand so I can select one. I compliment her pistachio-colored nails and she smirks, batting her lashes at me. The brunette clicks her lighter and holds it up to the cigarette, lighting it for me. She compliments my shearling jacket, and I smile, not knowing what to say. They make me think of the cherubim angels and the flaming sword flashing back and forth that God placed outside the East entrance of Eden after casting out Adam and Eve. We stand there at the corner in silence, two angels and one mortal with a flaming sword sheathed between my lips.

He never murders me. Instead, first thing on a Saturday morning, he says, I don’t want to see you anymore, I think. Those last two words a trap door for me to stumble through later, a glimmer of hope. I eat three pieces of semi-hard bacon over the sink before putting away the carton of eggs and frying pan that I brought out optimistically before receiving his message. Now, I can’t bring myself to eat. I want the sadness and hunger to become an indistinguishable sensation in my body. I have to leave now anyways if I’m going to make it to this fitting on time. One of my friends, a fashion student at the School of the Art Institute, asked me to model for his senior collection. Okay, he’s not really a friend. He’s just someone that I matched with on Tinder at least a dozen times during the past two years. We never hit it off over text. I saw him on my way to work once and he sheepishly waved, but not knowing how to react, I opted to ignore him entirely and scowled at my phone as if I received an unpleasant email. He asked me if I would model for him a few months later and, feeling I had to right some of my bad behavior, I agreed. I consider cancelling, but I’ve flaked on him four times already and can’t bring myself to do it again. At least not if I want to have a modicum of self-respect left. I manage to make it to my friend’s apartment at exactly the time we agreed on, so I stand outside for a few minutes before texting him, “Here.”

During the fitting, he has me try on eight unfinished garments and keeps asking, “Do you feel sexy? I want you to feel sexy. It’s always so obvious if the model hates the clothes and is thinking about how much they hate them.” I realize that I’ve been morosely quiet and that I’m holding my arms stiffly at my side. They seem so long and unwieldy. I want to do something with my arms, so I open my palms, a gesture that I read once is supposed to indicate vulnerability. I feel dumb as if I’m helping a friend move, carrying a box up several flights of stairs only to enter their new apartment and stupidly look around without any idea where to place it so I just stand there waiting for them to come and give me instruction. I smile to reassure him, but remember that I’m wearing two masks, so I say, “No, I really like your designs! They remind me of, uh, what’s his name, Walter Van Beirendonck?” I pretend not to know the designer’s name because I’ve never pronounced it out loud before and don’t want to embarrass myself. I don’t know how to say, “Your designs are great, I just feel like I’m going to cry.” There’s no precedent for that type of intimacy between us.

He asks me to get naked so that I can put on a bodysuit. The word naked startles me for a second. Would I feel better if he asked me to get undressed, to disrobe, to strip? Or maybe it’s not the word itself and actually the way he said it—as a command. I wait for him to leave the room before I take off my underwear, though I’m not convinced he doesn’t look. I neatly fold my underwear over the back of one of his kitchen chairs. While he stuffs my feet into some nonsensical garter design, I can’t help but stare at his receding hairline, it reminds me of the unofficial, dirt pathways that cut across the lakefront park, the grass wilting underfoot as disobedient pedestrians stray from concrete paths carefully laid out by city planners.

“City planners spend their whole lives studying to perfectly time stoplights, so I feel like it’s disrespectful for us to jaywalk even if there’s no cars coming. Sorry, I know it’s weird,” my internship supervisor at a small arts publication said this to me as we stood at an empty crosswalk in River North. No cars were coming from either direction. We were walking back to the office after attending a press conference at the MCA. I still had a cup of coffee that I made sure to refill before we left the museum and, unable to think of anything to say, I just sipped on my coffee and nodded. Except now I can’t help but think of her every time I impatiently cross in spite of the glowering orange hand insisting that I shouldn’t, questioning: What kind of person do I want to be?

I keep glancing at my phone, but the only notifications that pop up are from one of my friends. I leave the fitting and walk back to my apartment, sweating so much. When I get home, I strip down to my baby-blue underwear and stand in the kitchen. I eat a single piece of dry bread. I don’t even have the energy to spread some butter over the spongy sourdough. My friend texts me to say, “I’ve actually decided I’m going to look for another model cause u seem a little small to fill out the silhouettes.” No one has ever called me small before, sometimes skinny but never small (I’m 6’2” and quite limby), so I laugh. I laugh longer than is appropriate. I suppose I shouldn’t call him a friend anymore; we have no obligation to one another.

In The Albertine Workout, Anne Carson writes about the principal love interest of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time Albertine, “[She] keeps all her letters in the pocket of the kimono that she so carelessly tosses over a chair in Marcel’s room just before falling asleep. The truth about Albertine is that close. Marcel does not investigate. Knowledge of other people is unendurable.”2 I mull this over. I don’t know if I agree. Maybe I find the idea of knowing myself unendurable, willing to abdicate knowledge of the self and replace it with knowledge of another, so I decide I want to know everything about him. After each of our dates, I hurriedly write down everything I can remember that he told me about himself:

The names of your mothers; the names of your roommates; what you studied at school; the name of your hometown; how you were living out of your car your first few months in Chicago, which you only abashedly admitted after I pointed out the precariousness of the situation; your paranoiac superstition about cats and how you spit over your shoulder anytime you see one; how you once worked as a poison oak eradicator; how you slept in a hammock for several months after your family’s house was declared uninhabitable after a tree fell on it, not wanting to stay in the hotel with your mothers, who were too distracted navigating insurance to argue with you; about the time you attempted to summon a demon and were convinced it was tormenting you, jolting you awake with a loud noise anytime you were about to slip into sleep, so you salted the corners of your windowless room and tied a red ribbon around your finger to banish it; what you told me on the phone that made me wish we were together so that I could squish your puppy-eyed face into my chest, offering my body as a pseudo-womb so that you could be an unmarked body, not yet in the world again.

What do I do with these pages now, tear them out and burn them, scribble over them with a black marker, discard the whole journal? I can’t bring myself to do any of these things. Instead, I transcribe the following quote on a lavender-colored sticky note and place it over the first entry that mentions his name: “By telling herself it would just be a fling, [Reese] gave herself permission to fulfill every fetish the guy had ever dreamed of, to unearth his every secret hurt, to debase herself in the most lush, vicious, and unsustainable ways—then collapse into resentment, sadness, and spite that it had just been a fling, because hadn’t she been brave enough and vulnerable enough to dive super deep, super hard?”3

I’m still living inside and through the text of the novel. Except, I want to try something different, to set myself free through my own writing. You’re probably thinking, What the fuck do I mean by this? I mean: This text as a caricature. This text as the coy border between fiction and reality. This text as a self-deprecating satire. This text as a mischievous imposter. This text as the closest thing to honesty. This text as a false flag. This text as a rug pulled out from underneath me. This text as an artifact. This text as the distance between us. This text as the escape that fantasizing about you promised. This text as something living, breathing, heart beating. This text as a festering wound, stinking like a perpetually humid locker room, mildew blooming in every corner and crevice. This text as an admission—I am too tired to be rageful, so I guess I will just be tender. This text as a static image, certain of its boundaries. This text as a manifesto. This text as evidence that I can dredge up some day and say, “I used to be this person. Who am I now?”

I spent the idle days of summer between 6th and 7th grade begging my brother to let me use the red Motorola flip phone we shared so that I could text my friend Sierra. We had become fast friends the previous year because we were both transplants to the same middle school in rural Michigan, enrolled in a new advanced math and science program that bestowed us with the lifelong albatross of being “gifted children.” Our friendship was born out of necessity. Sierra was teased for being “mannish,” and I was cruelly shunned for being intolerably effeminate. Sierra was spending her summer at camp for the U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps, learning how to tie basic maritime knots, which she sent me the names of: Bowline, Figure-8, Square Knot, Clove Hitch. I spent an afternoon googling these knots and attempting to tie them on my own, imagining that I could impress her with my self-taught skill the next time we saw each other. One afternoon, I sent her a text saying, “i’m so glad I met you. We r gonna be friends 4 lyfe!” She sent back, “<3.” I always made sure to delete our texts before relinquishing the phone back to my brother.

That same summer, an intemperate, heaven-splitting storm descended one morning and turned the pitiful creek that ran between the houses of our suburb into a frothing brown lake of sewage, rainwater, and debris. As the storm waned, my siblings and I cruised around on our Razor scooters, surveying the damage with wide eyes. My brother pointed out a flotilla of twigs and litter slowly turning circles and tried to convince me it was some sort of monster that had emerged from the sewers. I ignored him. I lazily pushed my scooter forward and noticed something small, rotund and dark shivering near the edge of the sidewalk. At first, I thought it might be a rat but realized it was a baby muskrat as I got closer. I yelled to my brother, who was rolling his scooter back and forth over an earthworm, flattening and smearing its guts across the sidewalk. He came over. “What do we do? Should we leave it?,” he asked. I told him to go and grab a towel from the bin of work rags that our dad keeps in the garage. He came back quickly, and I carefully swaddled the muskrat in the pink, threadbare cotton. My brother picked up my scooter and folded it over his shoulder. As we walked back to our house, I moved slowly, holding my arms rigid so as not to jostle and traumatize the trembling creature.

I managed to convince my parents that we couldn’t take the muskrat to the Humane Society after reading on their website that they considered them pests and euthanize any brought in for rescue. So, my dad climbed up into the attic and brought down the wire travel carrier we used to use to transport our family’s sun conure to the vet. We cut out small rectangles of a rag to use as bedding. After a lot of consideration, I decided to name him Raymond. I woke up early each morning to nurse him with kitten milk replacement formula that my mom bought from PetSmart. I liked to watch him suckle from the tip of the syringe. He was so greedy and voracious, letting droplets of the formula dribble down his chin. I couldn’t feed him fast enough. I sent a barrage of grainy photos of him to Sierra, who responded, “Soooo cute!!!”

He must’ve died the same week I found him, but I can’t remember exactly, just that one morning I woke up and went to check on him and discovered that his body was stiff and odorous with death. There was still dried, crusted formula around his mouth from when I fed him the night before. I went downstairs and woke my mom up to tell her that he died. I crawled into my parents’ bed and cried while my mom tried her best to soothe me, running her fingers through my hair. At some point, she got up to make my siblings breakfast and left me there. I remember that we went to the Detroit Zoo later that day. I was uncharacteristically morose for a trip to the zoo, which was one of my favorite places as a child. I begged my parents to take me there for almost every single one of my birthdays growing up. Inside the North American river otter exhibit, I pressed my forehead against the aquarium glass and watched the otters lazily paddling back and forth. Later that evening, my dad helped me bury Raymond in the garden. We put him inside an old shoe box that I decorated, bedazzling it with sequins, glitter, and bits of ribbon. I wrote a small note and put it in the box with his body. It read, “I’m sorry I couldn’t take care of you better. Rest in peace, Raymond.” We buried him outside my parents’ bedroom window, underneath the vine-covered trellis that attracts hordes of shimmering Japanese beetles each June.

When I returned to school that fall, I was surprised to discover that Sierra was sitting at the lunch table with the same group of girls who told her the year prior that she looked like the illustration of Paul Bunyan on our homeroom teacher’s wall because of her square jaw. She had developed breasts over the summer, one of the first girls in our grade who did, and she was wearing a V-neck t-shirt that accentuated her coveted cleavage. I noticed that she had started wearing lipstick and heavily applied blush. She laughed with newfound confidence, like she knew that the other girls leaned in ever so imperceptible whenever she spoke now. Sierra never talked to me again, ignoring the text messages and, even more cruelly, the Farmville requests that I sent her on Facebook. At the end of the school year, everyone was exchanging yearbooks, and I ended up being passed her yearbook during the English class we had together. I scribbled a note on the back page, “Love you, H.A.G.S. –Riley.”

My mother once said to me after an argument, “You always love to side with the underdog, huh.” I couldn’t tell if she meant it in a good or bad way. She just looked at me as if she had finally discerned something she had never noticed before, as if reading a book only to realize during the denouement that she had overlooked some major plot point, thumbing back through the pages to try and identify the exact moment where she strayed.

She is right though. I’ve always sided unquestionably with the underdog. But why? Maybe my fear is that if no one roots for the underdog, who will root for me? Do I see myself as an underdog? Sometimes. Not always. More often than not. I don’t think underdog is a permanent position we occupy, but more so a vulnerable identity we slip in and out of depending on our circumstances.

My Uncle Charlie brought his new dog Daisy to our family reunion in 2011, which was remarkable because he had stopped coming to family events after his wife Ana divorced him for a woman after 13 years of marriage. He was left with their five children. None of us mentioned Ana, both out of polite respect and a fear that my grandma would start caustically spewing racial epithets (Ana left him for a Black woman, doubly insulting in my grandmother’s mind.) My Uncle Charlie was excited to introduce Daisy to my family’s 6-month-old puppy Isaac; He liked and commented on all the photos of Isaac that my mom posted to her Facebook. He tied Daisy to the metal base of a nearby picnic table since dogs weren’t technically allowed underneath the pavilion that my parents rented at Stony Creek Metropark—a local favorite for graduation parties, family reunions, and the cheap, shotgun weddings of young Christian couples desperate to consummate their relationship. The weather was idyllic, cloudless and not unbearably hot, and the turnout was uncharacteristically good for my mom’s side of the family. It was a perfect summer day, the kind where everyone is languid, oblivious and in good spirits, only concerned with whether or not there’s more beer in the cooler.

Most of my siblings and cousins were down by the lake’s edge, using nets to drag piles of muck up onto the grass and poke through it to find squirming, rubbery tadpoles or, if they were quick enough, one of the spry, emerald-green northern leopard frogs perched on the lily pads. Usually I would have joined in, but I had become increasingly forlorn and standoffish during the past year. I had no friends at school and felt the typical puberty-induced alienation from my family, spending most of my time on a laptop that I begged my parents for. My mom was fiercely opposed to buying me a computer at such a young age, convinced that I would use it to watch porn (which I obviously did end up using it for), but my dad managed to convince her that it would be fine in his usual convivial and fun-loving way. I frequented a number of online forums, antagonizing strangers by writing replies to fanfiction threads condemning homosexuality as unnatural and sinful and that people could only redeem themselves by repenting and accepting Jesus Christ as their lord and savior. Looking back, I think it was a pitiful attempt to justify my own behavior; I watched endless hours of gay porn every night, shamefully masturbating with one hand underneath my bedsheets and my other hand hovering over the keypad, ready to exit the page at a moment’s notice should my parents or one of my many siblings come unannounced into my bedroom. I never made a sound, staring at the multicolored butterflies and flowers that my parents had painted on the sloped ceiling using stencils. The room had been my younger sister’s before me and, despite promising to paint the baby pink walls a more boyish color and to cover up the decorative paintings before the room became mine, my parents never got around to it. I often came while staring at the same pink tulip, following a small dribble of excess paint that ran along the edge of the two-dimensional petal and pooled in a thin lip along the bottom of the bud. The shame made me fearful, and fear made me intolerable, always afraid that someone might ferret out my secret while talking to me, so I stopped talking, especially to my family. I spent the majority of the reunion sitting on the outskirts of the party at a picnic table that my older cousins had dragged closer to the pavilion so that I could sit in the shade and play with Isaac until he got tired and fell asleep. I cradled him in my arms. My two cousins Joslyn and Kacey came and sat on either side of me, cooing at him and stroking his velvety, downy fur. We didn’t talk.

Our state of content was shattered by my sister Carly shouting, a guttural cry of alarm that made my skin crawl with terror. Carly was standing near the picnic table several yards from the pavilion where my uncle had tied Daisy. Carly’s face was bathed in blood. It was running in syrupy waves down her neck and staining the collar of her pink t-shirt, turning it a dark black color. My mom got to her in record time and screamed, “Oh my god. It ate her face off.” I will never forget the sound my mom made, some primal wail of anguish. The type of anguish where you can think of nothing to do except grasp at chunks of your hair and pull with herculean might, hoping this new, specific pain will somehow replace the imperceptible pain coursing through your whole body. Carly went silent. She didn’t even cry when my mom picked her up. Daisy was cowering underneath the table, quivering so hard that I could see her shaking even from where I was sitting. My Aunt Carrie, a surgical technician and no stranger to blood, tried to soothe my mom and helped press a t-shirt (I can’t remember whose) to Carly’s face to slow the flow of blood. My parents drove her to the ER and left all of us at the park.

I didn’t move during this whole episode. I sat there holding Isaac and nodded silently when my Aunt Carrie asked me if I was okay. She explained, “Carly will be fine. Head wounds always bleed a lot.” Isaac didn’t even stir. Nobody knew what to do with Daisy. My Uncle Charlie stood next to her, wringing his hands and avoiding making eye contact with anyone, before he eventually left and took the dog with him. He passed me on the way to his car, pulling Daisy along behind him. Her tail was tucked between her muscular legs, her whole body trembling, and I could see the wet sheen of Carly’s blood starting to crust and dry around her jowls. I felt a sudden urge to kick her repeatedly in the ribs and make her squeal, to feel the blunt edge of my foot wallop and bruise her flesh until she splits open and bleeds across the dry grass, but I don’t move. Carly ended up being fine, but my Uncle Charlie had to put Daisy down. He had a four and five year at home, so my mom and aunt were adamant that he couldn’t take any chances. They threatened not to speak to him if he didn’t. When Carly found out that they put her down, she cried and said, “I’m sorry. She didn’t deserve to die.” Sometimes when I’m talking to her, I notice the jagged keloid scar running down the length of the left side of her face; she never mentions it.

The first night we’re able to touch each other, he asks me what the three crescent-shaped scars on my abdomen are from. Oh, those are from a surgery that I had last March, I say, and laugh as he prods them with his index finger and proceeds to inspect the rest of my body, flipping me over to locate and index all of my body’s blemishes. He takes note of the birth mark just above my right hip, planting a kiss on it, and the oblong splotch on my forearm, a campfire accident where my brother unintentionally flicked a blob of melting plastic at me. He also finds the lump on my lower left back, softly massaging it with the pad of his thumb. It kind of feels like a clit, he says, and we both laugh.

While we’re making out, my silver nameplate necklace snags on his shirt and breaks. The nameplate read, Gay Rage, an Instagram username that I came up with as a petulant, lonely teenager to avoid using my real name, mostly as a self-deprecating joke about how perpetually resentful and vengeful I felt towards the world as a closeted trans person who still didn’t understand that people were harassing and ostracizing me primarily because of my gender and not my sexuality. The username quickly became an online pseudonym for myself, a funny quirk whenever someone asked for my handle in person. I thought it was hilarious whenever someone I didn’t know referred to me by this moniker. It became a kind of informal philosophy for how I saw myself in the world at the time, as a spurned queer person who wanted everyone to suffer as badly as I suffered. A stoic understanding of the world as rooted in pain. The necklace was cheap and poorly made with a fine chain that had broken a number of times before and silver plating that tarnished to a dull grey after I accidentally wore it in the bath once. Each time, I used a pair of tweezers to re-secure the mangled link knowing it was a temporary fix. I see the necklace coiled on the bedsheet underneath him like a worm guillotined on the sidewalk by the wheel of a bike, and I surreptitiously place it on my nightstand so that he doesn’t notice, not wanting him to feel guilty. An FKA twigs song plays in the background. “So good to love / But when you give yourself away / It always hurts too much / So you pray to get it back.” I don’t fix the necklace this time. Instead, I throw it away unceremoniously the next morning.

After sex, we go to the kitchen to get water. “Should I wear underwear?,” he asks. Worried that my roommate might come out of her room, I say yes. I walk behind him, admiring the exaggerated sway of his hips, like the pendulum motion of a bull slowly trudging across a pasture—an overemphasized shifting of his weight starting in his waist and carrying up through his shoulders. While we’re standing in the kitchen, he asks, “what would you do if I spit this water at you?” I can’t think of anything to say, so I just laugh. He does it, spitting an entire mouthful of cold tap water onto my chest. I’m stunned. I can’t think of a response, so I sip my glass of water and pretend like I’m going to kiss him on the neck. Instead, I open my mouth and let a small deluge of water trickle down his chest and abdomen. We laugh quietly, aware that my roommate is asleep on the other side of the kitchen wall. I am reminded of one of my baby cousin’s baptism. The priest lifting a small, golden clamshell of water and pouring it over her head. I consider telling him about this memory, joking that we’ve just baptized one another, but remember that he was raised Jewish and likely won’t find this as humorous as I do.

I promised myself that I wouldn’t reference another novel, but I simply can’t help myself, so please allow me one final indulgence. After getting high while reading one night, I decided to send him an audio message of myself reading the scene from Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends where the forlorn, self-destructive protagonist Frances first kisses Nick, a married man: “I kissed him. He let me. The inside of his mouth was hot, and he put his free hand on my waist, like he wanted to touch me. I wanted him so much that I felt completely stupid, and incapable of saying or doing anything at all.” My mouth was cottony and dry as I recited the words. I added, I’ll probably regret this in the morning, sorry. I didn’t read the next few lines of the passage, “[Nick] drew away from me after a few seconds and wiped his mouth, but tenderly, as if he was trying to make sure it was still there. ‘We probably shouldn’t do that…’ he said.”4

He never murdered me. But the last time we saw each other, he handed my book back to me and said, “It’s not a romance novel, but it’s kind of a romance, don’t you think?”

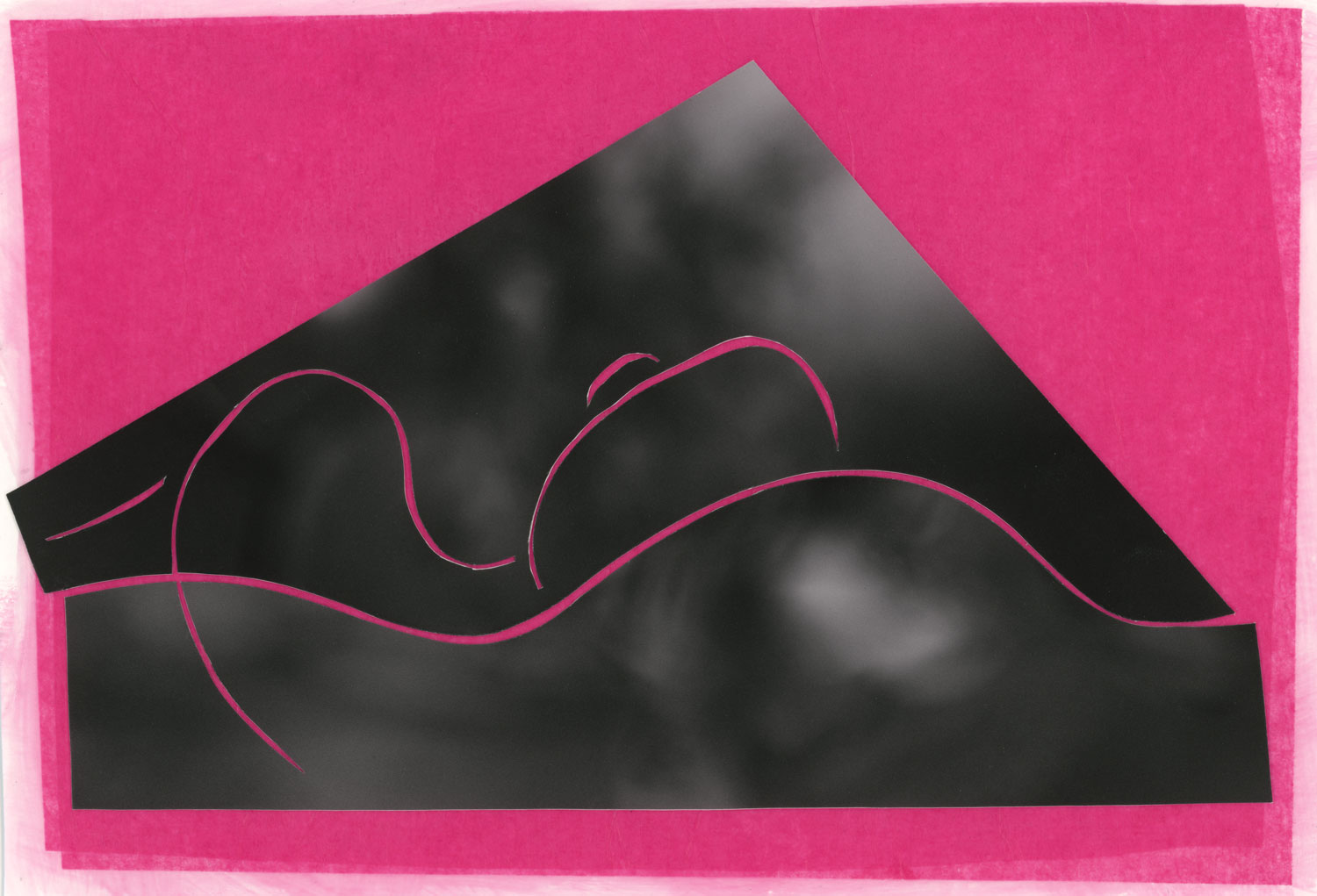

Featured Image: An abstract illustration of two people laying in bed together. The person in the foreground is laying on their stomach which is shown by the curvature of their backside. The person in the background is laying on their side with their arm over their lover. The image is cut out of a blurred black and white inkjet print on top of pink tissue paper. Illustration by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Acknowledgement

I owe endless thanks to Azora Jalili, Sara Carminati, and Taylor McGowan for supporting me during a vulnerable time. You all model the love I want to be in the world.

1Lin, Jeremy Atherton. Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. Little, Brown and Company, 2021.

2Carson, Anne. The Albertine Workout. New Directions, 2014.

3Peters, Torrey. Detransition, Baby: A Novel. One World, 2020.

4Rooney, Sally. Conversations with Friends. Faber and Faber, 2018.

Riley James Yaxley (they/them) is a writer, poet, and fundraiser based in Chicago, Illinois, living on unceded land of the Kickapoo, Peoria, Potawatomi, Miami, and Očhéthi Šakówiŋ peoples. They hold a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Writing, Rhetoric, and Discourse from DePaul University, specializing in professional writing and queer and feminist rhetorical histories. Riley started their career working at a number of arts organizations in Chicago, including Chicago Gallery News, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Wrightwood 659, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Riley is a regular contributor to Chicago Gallery News and ADF Web Magazine, aiming to uplift BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists and challenge systems of inequity within the art world through their writing.