This article was developed and written as part of Muña, an art writing program providing a cohort of writers the opportunity to critically and creatively engage with art writing strategies, readings, exercises, and conversations. The program is structured for writers to develop and refine their practices through guided workshops and peer-review feedback. Its task is to stir, incubate, and pollinate shared consciousness on holistic, equitable, and attentive art writing and language practices. Muña is a program collaboration by Chuquimarca

and Sixty Inches From Center.

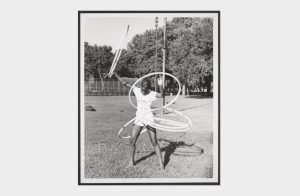

Death has begun by the time I arrive. The room is humid and smells like dried moss, melting wax, and the sour, pungent scent of flowers that have just begun to wilt. Vertical sprigs of twilight-blue delphinium arranged like a crown above her head have collapsed. She is reclining on two mounds of spongy moss, framed by a dizzying amount of floral: magenta lilies, blushing roses, and foamy, blue-and-white hydrangeas. She is naked except for a cutting of white hydrangea blossoms tucked between her legs. Her face is turned away from onlookers, who gather behind the line of candles and talk in hushed voices, afraid of drowning out the delicate piano accompaniment, as if we’ve somberly gathered before an altar to place our offerings.

We are eager to catch glimpses of her in the cleverly positioned mirror or the livestreamed projection. The role of spectator and voyeur comes naturally. Her stomach gently rises and falls. Her eyelashes flutter and she lifts her hand to scratch her face. We watch anxiously. Is she about to wake? But she simply shifts position, turning her face to us, and continues to slumber in her withering paradise, this monument of imported flowers. She is a still-life arrangement. She is a sleeping Venus. She is remote. She is unselfconscious. She is unposed feminine beauty. She is at rest. She is Celeste.

This interview was edited for length and clarity. Also available in spanish.

* * *

Riley Yaxley: Let’s start with some mythology. Tell me about the origin of Celeste. Where was the idea for this persona born? Who are her influences?

Ále Campos: It’s interesting, because, in retrospect, there’s a lot of things around the time when I started doing [drag] that feel like they aligned, but they’re not necessarily why I started doing it—you know what I mean? For starters, my friend Halo, who runs a restaurant called Lil’ Deb’s Oasis in Hudson Valley, is partially responsible for why I started doing drag. At that point [in my life], I wasn’t making any art really. When I was pushed to do this first drag performance at a New Year’s Party, something ignited for me. Funny enough, I think around the first, maybe second time I hosted and performed this little show, I had also broken up with my ex of almost four years. So it was kind of a breaking point—emotionally, romantically—and I was questioning what I was doing in Hudson Valley because I moved there with my ex. Discovering, falling into, drag, gave me a sense of purpose at a time when I really needed it because I didn’t know what was next. And, being a Capricorn, I really put my all into producing this show [Queer Night of Performance at Lil’ Deb’s Oasis] even though I had no experience producing, or handling performers. But it was something, I think, that was just in me and needed to be awakened somehow.

Maybe it’s a lack of research, but early on I wasn’t necessarily looking at other people to see how I should paint myself, or how I should dress myself, or anything. I really was just grasping at whatever was in the depths of my head—

RY: It’s intuitive.

ÁC: Yes, intuitive. No one taught me how to put on makeup. I just watched a few videos on Youtube and went to Walgreens and bought whatever I could get my hands on. And I think what I hold true about Celeste now, and from the very beginning, is that she taps into this femmeness, this sensuality and strength that is deeply feminine, and that’s always been there. So much of what I’m inspired by is the rage I felt growing up being told by my parents that I couldn’t be femme, that I couldn’t, you know, express my femininity in any kind of way. The experience of wanting to find purpose when I felt I had none and reaching into the depths of this [femmeness] coalesced at a really weird time. I didn’t even have a stage name for a few months. As I was discovering all these things at once, I wasn’t even thinking about it as a persona. It was just coming to me. I realized I needed a name eventually, like literally months in. There was a good friend of a friend. A good friend’s partner, Celeste, who I met at one of my shows. And we talked about our influences and music—Selena, cumbia, La Lupe, Celia Cruz. And I remember thinking her name was so pretty, and simple, but also really loaded.

“Maybe it’s a lack of research, but early on I wasn’t necessarily looking at other people to see how I should paint myself, or how I should dress myself, or anything. I really was just grasping at whatever was in the depths of my head—”

Celeste is also an idea. She’s not a character, you know. When I sit down to paint myself, I think I have a particular look, but I’d like to have the freedom to look and feel however I want.

RY: That’s something I’ve noticed. When I saw you at the Newcity [2023 Breakout Artists] exhibition, you were painted and dressed as your mother. It was one of those moments where you shapeshifted. Celeste became, in some ways, an effigy of your mom. It was a symbol of how you’re making sense of yourself, but also how you relate to your family and make sense of your family history.

ÁC: Totally. When you asked about influences where this persona comes from, I think, you know, growing up, my father was definitely the presence that said shit about my femininity. My mom never said that to me. It wasn’t easy coming out to her. It wasn’t easy coming out to her in all the ways I’ve come out to her, which has been a lifelong thing. But if I’m gonna go back in time and think about how my psyche has developed, how it’s been shaped and formed, it goes even deeper than before I was born. I think about my mother being a pageant queen and being a strong Scorpio woman. I don’t know. I just think there’s so much of her life that I’ve learned about over the last few years where I’m like “Wow.” I think she’s embedded in my work and embedded in Celeste more than both her and I know, sometimes.

RY: I’m so drawn to your performances and your work because of the way you’re investigating these familial relationships through drag, through this persona, is so interesting and unexpected. You use personal artifacts, like the photos of your mom and your grandparents’ love poems, and you use these objects to look at how you came to be and how you’ve been shaped as a person. And I’m curious: When did you start using these objects and how do you see them in relation to your work?

ÁC: I’m a very sentimental person. I’m very attached to objects. When I was in undergrad, I was really into making sculpture, dealing with objects and their symbologies. I would replicate and multiply certain things, you know, to see how that could shift meaning. Years later, coming to grad school [at SAIC], I think I sort of learned to intuitively weave together different elements in my performance, outside of clubs, because of the way I think of performance through the lens of drag. I know it sounds redundant because I’m obviously in drag in my performance work. But I’ve been really into voice since starting performance. I’ve been translating and recording these love poems that my grandparents wrote with my mother. So my mom’s voice becomes my grandmother’s and my mother’s voice is in my performance work. Funny enough, I never lip sync her. I feel like I have to give her the space to talk in my work. But she’s in the room with me, right?

“I think about my mother being a pageant queen and being a strong Scorpio woman. I don’t know. I just think there’s so much of her life that I’ve learned about over the last few years where I’m like “Wow.” I think she’s embedded in my work and embedded in Celeste more than both her and I know, sometimes.”

I think bringing these objects, whether they’re voices, or poems, or relics of my grandmother’s rosary—well, there’s differences. I think there’s two lanes. I love that you used the word effigies. There’s the pull of what I would call primary source material. It feels like an incantation or a calling into the room type of thing, a photograph, even. And then there’s the stuff that I’ve done that’s more of a reimagining like the Newcity performance. I had a sash that I made, but it’s blank. And it looks exact, and the dress I wore is a replica of my mom’s that my friend Faviola made that’s based on the image. Those things are interpretations rather than a direct through line. But they work together and do similar things. They helped me reach back. Sometimes I think these things exist only for me. There’s a photograph of my grandmother holding me as a baby. Not many people will catch that detail or understand the reference. But it creates the psychic space for me, you know what I mean?

RY: Yeah, I think that’s what I responded to. Because you’re recreating this image from the primary source in a sculptural way. I remember I was terrified when I saw you sitting in the corner [at the Newcity exhibition]. You felt both inside the room and outside it. You created this experience for yourself, this interpretation, as you said. And I think we all do that, with our parents or our family. We take things from them. Their personalities. Their antics. We try them on and discard them. You’re carrying this lineage in some ways. You’re adapting, interpreting, figuring out what works for you and what you want to leave in the past—

ÁC: That performance is funny to me because it’s so simple, the arrangement of the fabric, the lily, the tape player, and the photograph. But it felt so charged. If it feels charged for me, I know it feels charged for the audience. But I also like that feeling of what you said, being really present in the room but also outside the room. I felt more outside the room than anything. There’s something you have to do when you do this kind of endurance-based performance, like there’s this vibration. You’re kind of existing within planes. You’re like, “Okay, I have to calm my body down. I have to breathe. I have to literally slow my heart rate down in order to hold this for so long.” But then your mind goes everywhere. My mind goes as far back as when that picture was taken. To what I did yesterday. You know, it’s weird how much your mind can travel when you’re performing. I think that’s what’s intimidating to some people.

RY: And then you started lip syncing—you’re so good at crowd work—and you came out into the crowd and demand—

ÁC: Like stepping out of the photo.

RY: Yes, exactly. And you ask them to recognize the experience you’re creating for them. So much of your work revolves around visibility and invisibility and seeing and not seeing—

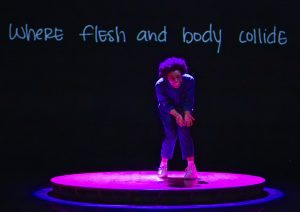

ÁC: Yeah, I had a studio visit with a curator from the MCA yesterday. I was showing video documentation of my performance at the closing of the Hyde Park Art Center’s Ground Floor [biennial] exhibition this March, and she mentioned that there was a part of the performance where, after lip syncing, and dancing, and doing all this gestural movement, I start to read this acceptance letter speech. She pointed out that there is something really jarring and important about hearing, getting to a point where you hear my voice after watching this enigmatic image of a person moving and dancing and lip syncing. To hear my voice is grounding. I was gonna say that only happens outside of the club, but I’ve gotten the chance to do stuff like that at Reset with Ava [Wanbli] where I’ve walked around and held gaze with everybody for a moment and embraced people. I feel like I love to set up the performance and then break it down. Because there’s always this weird distance that happens when you perform. There’s a gap that’s created out of respect, out of the spectacle of it all. That’s what the lip sync does in that [NewCity] piece. It sort of brings everybody back in the room together. It kind of humanizes me again.

RY: It makes sense. You’re lip syncing the song of another artist or singer, embodying their emotions. You don’t necessarily have a “voice.” And so the moments where you do, it becomes really powerful. Even two nights ago, when you read your poetry at Together Again, it was really nice to have that moment. To realize, you’re not simply channeling these other entities and voices. You’re at the core of this work.

ÁC: There’s a through line, totally.

RY: I was poking through your website and saw that you had done a video of that piece [“A Perpetual Whisper In Each Other’s Left Ear”]. I’m curious, especially thinking about your Hyde Park Art Center performance, how this persona has allowed you to grapple with being a part of a diaspora, and how it has helped you heal your relationship to the motherland. How do you navigate those threads? How does that continue to show up in new iterations of your work?

ÁC: I don’t want to speak for everyone, but I feel like I’ve noticed that a lot of my contemporaries are doing very similar things. A lot of us are returning to our family’s traditions—the food, the music, the textures, the colors, the patterns. Often, you know, there’s a lot of Black, Brown, Asian, and everyone in between, who are repurposing their archives, their family archives. I think it’s a really risky thing. I think it is risky for oneself. It’s just something that can be really difficult and hard. I find it to be something that can be kind of difficult.

“I don’t want to speak for everyone, but I feel like I’ve noticed that a lot of my contemporaries are doing very similar things. A lot of us are returning to our family’s traditions—the food, the music, the textures, the colors, the patterns. Often, you know, there’s a lot of Black, Brown, Asian, and everyone in between, who are repurposing their archives, their family archives.”

For example, you know, I think about my grandmother, who is no longer with us. There are times when I’m using her words, and I think, “Would she like this?” If she really knew what I was doing with her stuff, would she? I’ve had to put that negativity at rest and say, “No, actually, my grandmother would love this.” I don’t think we give our ancestors enough credit. I think our ancestors were always imagining forward thinking people, you know? There is always a push to move beyond where we are. Why would my ancestors not have imagined something I’m currently imagining? I can’t imagine any other way to fucking do all this than through Celeste? I’m not a painter. I’m a sculptor. I do some things that resemble other [artistic] practices. I think there are sculptures, images, and intangible things that unfold in my performance work. But I’m a performance maker first and foremost, and I can’t think of any other way to tackle these things and to mend these severed ties to El Salvador, to my mother, to my grandmother, all of these things.

Really, it’s healing. It’s healing because of the context, right? I get to try out and feel all this stuff in front of an audience who, for the most part, love and support me. Even if I don’t know the audience—like I performed at the Other Art Fair where people don’t get me. I wasn’t specifically referencing my mother in that performance. But like we just said, it’s there always. And even the support from a random person reminds me that I’m moving in the right direction, I’m doing the right thing. There’s room for trial and error in performance. There’s performance classes that I’ve taken at SAIC where there was the idea that you don’t know until you do it. You learn and discover the performance in the act of doing it. And I think you don’t just discover the performance, you discover yourself through the performance. It’s wild how much is packed into like one moment, or the 30 minutes of a performance, you know?

“Why would my ancestors not have imagined something I’m currently imagining? I can’t imagine any other way to fucking do all this than through Celeste?”

RY: I can’t imagine your work taking another shape. You’re embodying how you relate to femininity, how your ancestors have experienced it, for an audience in this way that I can understand. And there’s a question of futurity in your work, where you’re asking, “What does this look like for me, as a queer person, as the child of immigrants?”

ÁC: Definitely. Yeah, the gender thing is sometimes a lot for me to handle because I’m like folding both identities [into my work]: Being a queer, non-binary, trans person and also being Salvadorean. It’s all happening at the same time. And sometimes I wish I just made something that wasn’t so packed and heavy, but I can’t help it, you know? It’s been a way for me to grapple with it, grapple with all of it. And yes, we make sense of ourselves through performing gender as we move through the world and also onstage. But I think a big thing is also that Celeste is a reflection of the room. There’s a line. There’s something that I wrote. I’m forgetting what it was, but it’s the idea I explore a lot in my work that you’ve noticed. The reflection goes both ways. Sometimes I actually physically use mirrors in my work because I want to remind people that, yes, I’m seeing myself through them, but I want people to see themselves through me as well. I strive to create a holistic experience where other Brown folks can relate, where I can relate to them, but also anyone can really.

RY: Part of that is captured by the sculptural elements that remain afterward. I’m thinking of all of these tangible leftovers, but your makeup wipes in particular. They become imprints, effigies, one way of looking at the past, whatever iteration of Celeste. It allows you to be one thing and to become another. As an audience, it challenges us to see how this person performs identity onstage, questions their gender, and their place in the diaspora, while also looking at objects as an accumulation of this process.

ÁC: That makes me think. It’s funny because I tend to change really quickly after I’m done with a show. I come out in my face and hair, but I’m wearing my normal clothes. Do you think I feel different to you?

RY: I think so—

ÁC: I will say that I imagine I feel entirely different than when I’m onstage. I can understand that. There’s a separation. I mean there’s a separation there for me. It’s being on versus being off. But people who don’t know me must be confused. [Laughs] I wonder what people think sometimes because it’s a continuum, but it’s also not.

It’s funny because I don’t do those wipes at the club. I’ve actually only done it once in a performance where I’ve taken my makeup off, and that felt wild to me because I’ve never done that. I don’t think I’ve ever done this since. It would be interesting to explore that more because it felt more emotionally intense than what I’d been doing the whole performance. It’s like stripping yourself naked. But it’s such an intimate time when I get home, and I’m just in my bathroom getting this shit off of my face.

RY: Well, to me, they feel like mementos. Looking at the makeup wipes themselves—

ÁC: They’re somber.

RY: Your eyes are closed. Your face is at rest. It’s this image. It feels like the weight of the entire performance impressed into the cloth. I was thinking about it last night, and they remind me of how snakes or lizards—

ÁC: Molt. Totally!

RY: So they have to break out of their skin and leave behind a shell. They shed in order to become something new.

ÁC: I’ve never thought about it that way. I love that more than the constant reference I get to the Shroud of Turin.

RY: Because, to me, it feels more like documentation and accumulation. You have that with other things—the gloves from your Hyde Park Art Center piece.

ÁC: It’s interesting. There’s certain things like the wipes that go over really easily and will sell. And I just love sharing them. And then there’s things I feel more intensely [about], that I need to keep them in my universe, like those gloves. Those gloves are about to go to an exhibition at the Boulder Contemporary Art Museum. And there’s this question of whether or not they’re for sale. I did put them up for sale at the Hyde Park Art Center, but I just feel like they’re an important part of my performance archive. Unless somebody was like, we’re gonna pay like 10k, 20k, for them—when I’m 50 probably. [Laughs]

RY: That’s the difficulty of performance in particular. Number one, it’s not valued. Number two, it’s not [sellable] in the same way as a painting. You know, I have a friend in New Orleans who made this incredibly gorgeous painting that took her several years. And she considers it her magnum opus. It deals with her assumption of femininity and her relationship with her mom and grandmother in a very similar way. And she’s like, “I would never sell this one. I can’t physically sell it even though everybody wants to buy it because it’s my best one.” She has to hold on to it because, again, it holds that little bit of life in some way, that spark, like your primary objects and photos. I think there’s always this urge to make everything sellable—

ÁC: Yeah, well, especially with drag, the lifespan of drag performance is so short, like, I mean, not the person. Well, sometimes the person. I feel like in Chicago, in the drag scene, you see so many of these girls come up so hard. They fucking supernova, and then they burn out really quick. And then [the scene] moves on to the next girl, the next girl, the next girl. And it’s insane to me. And also insane to me that people have to produce work so rapidly.

RY: Even just as a spectator. Drag is so special, such a welcoming community in Chicago, but it becomes a parallel to the rat race of the art world at times. So often you’re not being compensated in any way.

ÁC: Yeah, it’s funny how they kind of operate in similar ways. And I’m trying to navigate them both constantly. The [MCA] curator yesterday said something to me. She said something to me I have never thought about performances and how they’re priced. She told me that I should consider that it’s the norm, when you make a performance piece and are going to tour or show it, that its highest value will be the first time you ever perform it—and the last time you show it. But every time in-between them it goes down in value. She said to think of your performances as intellectual property. You spend all this time, all this work, to create this thing that you’re not gonna be able to benefit from any more because you’re putting it to rest. That is actually when it will be the most expensive, or the most expensive besides its inaugural moment. I’ve never thought about performances like that. When you put something to rest, no one ever gets to see it again.

RY: At that point, if you’ve performed it numerous times, you’ve had the chance to develop, grow, and shape it into this final version.

ÁC: Exactly, that makes sense.

And, you know, it’s funny, my thesis performance that was at the Hyde Park Art Center came with me to my solo show in Denver, Colorado and is now going to go back again to Boulder, Colorado. I think this is really the last time I want to show it, not because I hate it. I think it’s all deserved: all the love and support that it’s gotten. But like that performance, “Con Esos Ojos” was what I called it, like “With Those Eyes,” that performance came together at a time when my grandmother had just passed away. I went to El Salvador for the first time and was like, “Whoa.” I feel like I was reckoning with a lot of these things, of feeling at home and at peace and really one with the landscape there. But I was also feeling estranged, very American and very gay in a place that’s not safe to be gay. Again, diasporic, like existential crisis, all of these things.

That performance deals with a lot of those initial questions. The whole piece works with green screen and camera work to imagine my body in this landscape. “Do you see yourself in all of this?” is the question of that performance, a question my mother asked me as we drove between volcanoes and fields of ripe sugar cane. I think I’m over that. There’s only so much that you can ask yourself. I’m conceptually, spiritually moving on. I’m already devising and have started working on part two of this project, which answers a lot of those questions. Or it looks to try and answer them. And that’s what I’m excited about now. But the challenge is always where, when, and with what support. So it’s weird to put a stamp of time and money on something that is a lifelong work. I think this thing we’ve been talking about, going back in time, [to the] the motherland, and this deep soul searching. I know this reparative work is going to be a lifelong task for me. I’m okay with that. But the real task is putting it into stages and boxes that can benefit and support me.

RY: Well, and to create moments where you can show that journey as a [performance] work.

ÁC: Show it as work and show it in a very clear way. I don’t ever want to show work that doesn’t feel clear. I want clarity for myself and for my audience.

RY: Hearing you talk about this experience of showing work that you’re tired of performing makes sense to me. It’s a natural experience. Can you tell me more about the new version of that piece that you’re working on?

ÁC: There is a part two. I’m thinking of it as a sequence. It helps me think of them as chapters. This performance is called “Al Otro Lado,” which means “On the Other Side.” I called it that because I feel like it directly refers to some text in the first chapter of this series. And also the idea of what it means to be on the other side of all these feelings of estrangement, etcetera. There’s a big moment in this performance. I’ve called it an acceptance speech because I love the idea of referring to my mother’s tape—that I haven’t heard—which isn’t actually an acceptance speech. It’s her stepping down speech. It’s the idea of coming to terms, like a double entendre. Is that what a double entendre is, when something means two things at the same time?

“I’ll always be the alt girl, and I’m okay with that.”

RY: Yes.

ÁC: [Laughs] If the main question in part one was, “Do you see yourself in all this?” The second part is basically saying, “Yes, but it’s complicated.” It dives more into the nuances. It’s less pondering and goes straight to the gut of what it means to be in between. I think the first one is very lackadaisical and kind of hypnotic and weird. I wanted there to be a lot more delineation, in the movement, the images, the text, and the music in this second one.

RY: That development feels very natural.

As you grow as an artist, you’re becoming sharper, you have a clearer sense of what it is that you’re doing, the shape your work will take. Seeing your drag performance alone, it’s so evident that you’re maturing in this specific way, trying new things, but also retaining your center. And that’s so exciting, to move from that younger phase of feeling lost, asking a lot of questions, trying to figure out what’s going on.

ÁC: I was recently encouraged to not separate the worlds that I work in, like how my work looks both in the drag world and the art world. That’s a continuum, and I’m the through line. I think I’m always battling a sense of imposter syndrome in whatever space that I’m in. Regardless of the gifts and honors that have come my way, I always feel like I’m the odd one out or something. But I think I just have to trust more. And trust my presence. Trust that I’m a good performer. I understand that people are like, whoa, when they see me perform. But I’m such a continuity bitch. I want my work to feel cohesive and whole, even if I have divergences, in one-off collaborations or projects that I put myself into. I want them to feel consistent. And it’s already baked into it. Acknowledging that will allow me, has allowed me, to spread my wings, you know?

RY: I think it’s helpful to remember, to see the spaces you’re creating, like with Together Again [at Cafe Mustache]. You assumed this role and uphold the value of bringing people together. You’re a performer, but you’re also creating these incubatory spaces for other people and the community. And I think that’s what I love about Together Again in particular. As you always say at the show, it’s making Logan Square a little bit more queer. And I love it. Because it’s like the one queer show, and it’s walking distance from my apartment. But it’s also a variety show where you give people of all these different mediums the opportunity to be vulnerable onstage.

ÁC: The thing that’s really special about that show, and I feel this way about Rumors too. Rumors is in collaboration with Miss Twink Usa and Ariel Zetina, who are huge club staples of Chicago and internationally. I think that the desire to come up with shows like Together Again is because I want to be immersed in spaces where I feel really comfortable. And the truth is, I don’t feel all that comfortable in club spaces. I know that about myself now after moving to a big city and trying to pursue drag as a “career in the city.” There’s particular bars and places, like Berlin, that I love. Do I feel comfortable at other places, other clubs I won’t name? No, not really. And that’s just energetically the space it is. Putting together a show like Together Again has been really rewarding because, every time I do the show, I’m told by the people that it’s a space where they feel comfortable, that they love, and that they feel inspired by. That feels different. And I think it’s a reflection of what I do, the kind of drag that I do, and the kind of work that I make, even though it brings together a bunch of acts and talents. Work that I could never even dream of making myself. But the spirit is all the same. And I can’t wait to see it grow more.

RY: I think that’s exactly it, it’s this alternative space—

ÁC: I’ll always be the alt girl, and I’m okay with that [laughs].

RY: In reality, the Boystown strip is the image of drag in Chicago. And some people push that boundary, like Siichelle and Irregular Girl with Strapped. But a lot of spaces on the strip feel hostile for performers, so high stakes and brutal. And you’ve created this vulnerable community space that feels deeply caring. It’s radical to me.

ÁC: Isn’t it crazy? Like Cafe Mustache is not a gay bar. If you go there on a Saturday or Sunday during karaoke, it’s full fucking hetero, straight ass people unless you bring a whole group of twenty people with you who are also gay. But a place like Hydrate, which is a gay club, can feel hostile and kind of intense and scary. This show makes Cafe Mustache feel like a queer haven for a night. You look around the room and there’s more trans people in there than any night at Hydrate. You know what I mean?

RY: I think that’s what I’m trying to get at. That’s what feels so important right now. Being visibly queer and/or visibly trans can be so horrible and dangerous. And I have my own feelings about Boystown. It often feels deeply transphobic and very alienating. That’s one thing I respect about you as a performer and as a host is that you create affirming spaces. You’re invested in the community and the other artists that surround you. I remember the first time we met. It was at Bun [Stout’s] runway show “Local Legends.”

ÁC: Yeah. Oh my gosh, totally.

RY: It was this constellation of people that I’ve met through Bun and all these nightlife spaces. People who have this ethos of like, “We’re coming up together. I’m going to take care of you because I know you’ll take care of me.” And that’s so important as queer people to me. Oh my god, I remember I had a question about when y’all went to EXPO [Chicago] in Bun’s “Hell is Real” skirt because that was the skirt I wore during the show. You took it to EXPO, which I thought was badass. EXPO is the epitome of the capitalist rat race of the art world. And I feel like you were thinking through visibility and invisibility where, as a queer, nonbinary, and/or trans person in the art world, your identity becomes sellable. But only when the market finds it profitable and usually only for a select few individuals. Can you tell me more about how that came together?

ÁC: I want to make a tradition of it every year. It’ll be my own little Met Gala moment. I was having a lot of feelings because, being a part of the CAC [Chicago Artists Coalition] and coming out of SAIC, EXPO is always this thing they’re pushing you to participate in. This was my third time going to EXPO. I don’t think I could ever go back to EXPO in any other way. My friend Kezia Waters did this performance at SAIC. They had this text written on their back that said, “The art world is a death cult.” And I thought it was so beautiful to wear that in the institution that is breeding artists for the art world. And that inspired me to make a statement at EXPO. I remember thinking about artists I knew that had like big statement pieces.

Of course, I immediately thought about Bun and that dress. I thought it would be a wonderful opportunity to make a splash at EXPO. Whether or not people understood this, my driving motivation was this frustration with the commercial world and how there’s no room for performance makers. People can’t easily put a price tag on us. We can’t be owned. So I decided to make room for myself. But I didn’t realize this until we got there—me, Ruby Que, and Bun were getting dressed in the parking lot at Navy Pier—that I would be carrying my friends with me, who I collaborate with all the time. Ruby has documented so much of my work. And Bun and I have worked together on a lot of outfits and other collaborations.

RY: Like the breastplate that you wore for Crash Landing?

ÁC: Yeah. So it felt like this really beautiful moment of solidarity. Ruby pointed it out. “All three of us are artists that make work that is not easily quantifiable and sellable.” Ruby makes video work and Bun makes [augmented reality] poetry and sculptural stuff for the club. And I’m a drag performer. And people were gagged. People’s heads were turned. I couldn’t even walk more than 20 feet without being bombarded by cameras. The last thing I’ll say about that is that it was just really wild. Because I went into it thinking, “Oh, this is gonna be really easy. We’re just gonna walk through.” But it was a performance in and of itself that I was not even mentally prepared for. So next year, I know what that feeling is gonna feel like, and I want to have a trail behind me. You know what I mean?

RY: EXPO has some performances, but it’s like two or three for the whole week, which is almost nothing. So of course people were shocked by you. People want to see it. You activated the space in a different way.

ÁC: You know, the thing is, I’m an incredibly shy person. I don’t like attention, believe it or not, especially publicly like that. And I think I need to own myself a little more because you really have to commit if you’re doing something like that. I’m thinking of being bolder and louder next year. It has to be a fully unapologetic gesture. And I felt like I was carrying the weight of the drag world on my shoulders.

I think so much of the motivation behind the performance at EXPO or Together Again is that I’m really aware of all the people that helped me and got me to where I am, so I can’t imagine not facilitating that for other people. It just comes naturally.

RY: The last thing I wanted to touch on is your upcoming performance for Jude Gallery, which will have likely happened before this interview is published.

ÁC: Yes, I have an upcoming collaboration with Vince Phan, who came out of sculpture at SAIC with me. We’re both Capricorns. We took some classes together at SAIC. He’s a florist and a lot of his sculptural work deals with similar conceptual ideas. He’s Vietnamese and, you know, battling to stay in this country with this fucking legal system that is a shithole. He thinks a lot about what it means to have this “alien” status in America. And he does that through these really beautiful living sculptures with soil, flowers, and other kinds of organic materials. He approached me about doing a durational piece and installation inspired by this piece he made a while back.

“His sculptures decay over time. The five-hour performance is very much inspired by still life painting. We’re creating this immersive installation of flowers that I’m going to lay in, just for the audience’s gaze.”

ÁC: We quickly realized how much overlap there was between our work and some of the interests we’re exploring, such as endurance, ephemerality, time-based work that are still, quiet, and slow moving. His sculptures decay over time. The five-hour performance is very much inspired by still life painting. We’re creating this immersive installation of flowers that I’m going to lay in, just for the audience’s gaze. It’s called “At Rest” because we wanted to subvert this expectation of intensity around drag performance where the drag performer always has to be “on.” We’re creating this environment where I can be at rest.

This is gonna feel really different and special because I’m working with somebody else who’s creating the environment. And the other situations I’ve created for myself with this sort of format have been super uncomfortable for me physically. I told Vince, “We need to make this pedestal, or bed of soil, super comfortable.” I want to feel like I can lay down and fall asleep. And have people look at me that way and be able to experience this sense of spectatorship and distance and admiration, but at a state of rest.

We’re going to play with the lighting and the whole space. There will be a live feed. Because of the way the gallery is set up, you won’t see me right away. The first thing you’ll see is a projection of a detail of the performance and then you’ll have to walk around this wall to find me on the other side. There’s these ideas of vision and gaze and looking, but also this idea of the performance dying over time. The flowers will wilt and reveal more of my body. So much of my work is loaded with so many ingredients. I’m excited to make something that feels simple, straightforward, and poetically charged.

And also to not have to run around the club [laughs].

About the author: Riley Yaxley is a shameless navel gazer. A notorious backtracker. An essayist who believes in saying what you mean and then deciding you mean something else entirely. The middle child of seven, Riley was born and raised in a Detroit suburb and currently lives in Chicago on the stolen land of the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa peoples.

About the photographer: Tonal Simmons, they/them, is a Black queer non-binary artist who is a writer, photographer and painter. Their photography and painting seeks to examine the similarities between flowers, growth, and Black queerness. While their writing explores the idea of DEI within art, creating w/chronic conditions, & lack of access to art for Black and brown creatives. You can check out their personal work at www.tonalscorner.com.