This essay was produced and co-published in collaboration with Amplify Arts, an incubator for just and equitable futures in the arts. They support Omaha-area artists working to affect meaningful change with funding, space, and opportunities for collective learning. Learn more about their programs on their website.

I went to visit the Bemis Center on Saturday, August 12. My visit was intentional. I needed to see Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s show, Eat Bitterness. The viewing of her work in this show was necessary for my task as a contributing writer for the ongoing collaboration between Bemis Center, Amplify Arts, and Sixty Inches from Center.

I didn’t anticipate coming to the artist’s work with a new depth and experience of grief and mourning as I did.

My mom passed at the end of July.

It is Wednesday, August 23 and I have a draft due to Sixty on Friday, August 25. And so I will do my best to write what I know, as Bemis Center’s critic-in-resident Chenoa Baker says, and write about how I showed up to Jennifer’s show, where it took me as I engaged and witnessed it, where I am, and what questions are with me now because of it.

Upon inquiring and accepting this opportunity to write for this show, I had been a resident of Omaha. I relocated back to Lincoln, Nebraska in June of this year, where I am originally from. Not only was I needed at home with my family to act as one of my mother’s primary caregivers during this season of transition, I was also separating from my long-term partner. Summer 2023 really came for me.

The night before my visit to Bemis Center, I was running around and supporting a monthly concert series called We’re In the Back that I curate in Lincoln in collaboration with a few others at an artist-run space called Project Project. I made a plan to see Eat Bitterness on Saturday and had to coordinate where I could stay for the weekend. Fortunately, I have friends who live and work in Omaha and when I need to live and work (short-term, even if it’s only a weekend) I know who to reach out to. As an independent/freelance artist + organizer, knowing who your people are wherever you go is life-giving, saving, restoring… especially when the world keeps turning (regretfully so) after defeating loss.

After the event at Project Project ended, a few of us of course gathered to decompress and/or check-in with each other, flirt even, at a locally owned bar that we all felt safe in–and just as importantly, a bar that had food and drink on the menu. My friend who I had rode with to the bar was the friend I was planning to stay the weekend with in Omaha. We got drinks and tater-tots and talked about what either of us had planned for the weekend. She knew that a visit to Bemis Center was of priority for me and we moved through the rest of the evening and into the morning with intention and purpose. Which is to say, we had one drink at the bar and called it a night, relatively early for two single femmes of color with nothing to lose.

In preparation for my visit to Jennifer Ling Datchuk’s show, I went to her website to familiarize myself with her work and story. I listened and read interviews. Jennifer Ling Datchuk is a Chinese American woman who was born in Warren, Ohio and raised in Brooklyn, New York. She currently lives and works in San Antonio, Texas where she is an Assistant Professor of Studio Art at Texas State University. All of this fundamental information is important to learn, but for me as a writer I’m much more interested in the questions the artist is sitting with and the specific anguish that might drive her to create.

Something that stood out to me about her story is that she has chosen to disconnect from her family because she wants to live a happy life, which led me to deeper, more provocative questions about why this was best for her and if this decision has impacted how she shares stories about her claimed ancestry through her work. I also came to find that Jennifer and I have a lot in common. We both are artists and ethnic women with AAPI heritage who carry big thoughts, questions, and feelings around gender/gender roles, home, lineage, family, and identities. Jennifer is a mixed-media artist who works with ceramics and porcelain, and other materials often associated with historically traditional women’s work. She does this and also questions Western Ideologies around identities.

“…part of my work are the conversations that happen from the kind of extremely difficult topics I’m dealing with in terms of conflict as experienced with identity, race and gender. These come from personal experiences that have happened with me and my family.”

Jennifer Ling Datchuk

I myself, as an artist working in performance and song, find myself deeply exploring—constantly—internalized notions around power and value as a femme-woman. Who holds power? Why? How do they use it? Whose values are these? What intrigued me most while researching Jennifer was learning how she talks about her work, how she sees and moves through the world, and the themes that appear within her work—which seem to be influenced and grown through her third culture experience.

“…I can’t fully embody everything Chinese nor fully embody everything on the other side of my family so this third culture allows me to kind of examine both sides and make work from that perspective.”

Jennifer Ling Datchuk

In a hyper-identity culture, this perspective gives a sense of clearing and space for new stories to be told from the experiences that live in-between and on the margins of society even within racial and ethnic groups. There is value in her use of preserving and honoring the stories of the femmes in her family that came before her time, while also building and co-creating her own story. For me, when I think of thirds in this context I’m also thinking of past-present-future, as well as the term third-space as it is used in architecture: a space that is neither home nor work. It’s as if her work nods to time-traveling, and how women cross culturally still struggle to find safety and equality. And here, perhaps that safety can be found in this third space (Jennifer’s world building as an artist), as a third culture woman, time traveling; persevering, honoring, and creating.

“…I learned that the ancestral home in Guangzhou, China contains a plaque that traces my Chinese family back 28 generations but only in the name of sons. So, even my story, my mother’s and my grandmother’s stories don’t count in the records of my family.”

Jennifer Ling Datchuk

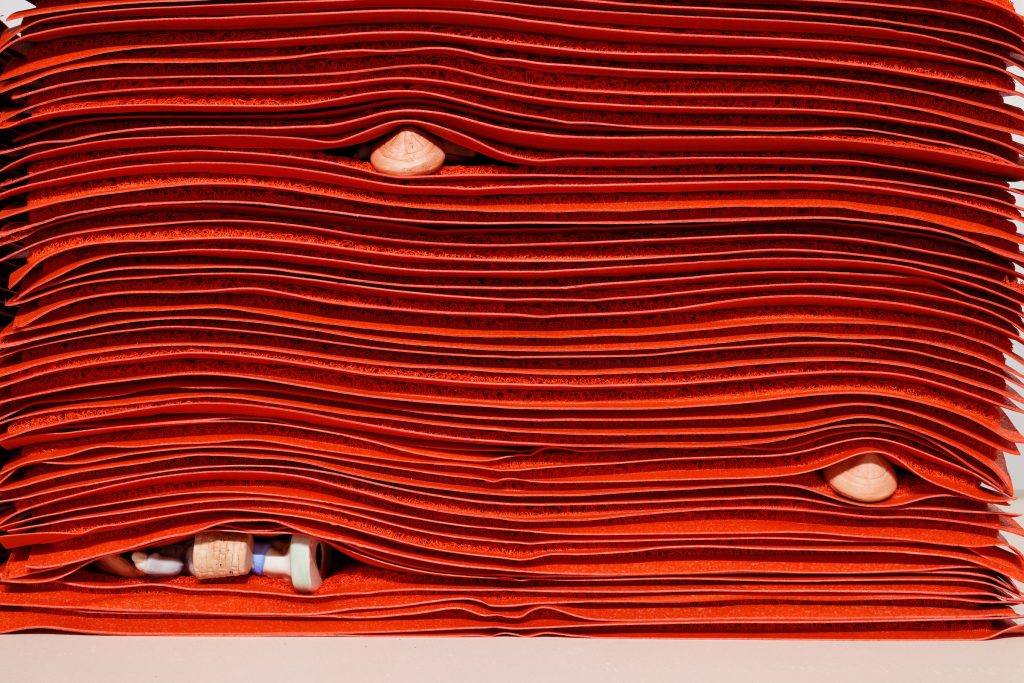

Entering Jennifer’s show, I am met with the custom red mats that make her piece Live to Die. Fifty striking red welcome mats, stacked on top of each other, in multiple piles—separated by two inches—are sitting on a three tier white metal shelving unit. At a distance you can see small porcelain pieces inserted at different points of each pile. These porcelain pieces are “China girl” figurines from a 1970’s hobby mold. After reading the wall description and Jennifer’s title of this work I was able to see the contrast she is pointing to between Asian women, labor, production, and the economic weight and toll this puts on their bodies. Her use of the welcome mats also makes me think of precision and mass production as survival mechanisms in the labor force and so too, a metaphor for the crushing, lethal weight of global capitalism.

The “China girl” figurines make another appearance in Jennifer’s video performance piece, Tame. In the video, the view is top left, angled down. We don’t see Jennifer’s face, only moments of her profile, left ear and side of neck and the red basket in which the figurines are packed. Her hair is in two long braids and one white hand comes in and out of frame, pulling her hair and head back, making the figurines jostle in the basket. When the jostling happens the view zooms to the front, center of the basket and Jennifer’s hands. Tame holds tension, not only in the physical pulling of hair but also within the audible clinking and clanking of the porcelain pieces made by the artist. When will something break? What is the breaking point? The intention behind the style of Jennifer’s hair and the pulling seems to speak to a metaphoric correlation between domesticity and control. Domesticity is highlighted through the braids of her hair, resembling a horse bridle, and the white person doing the pulling is the one in control. This 3:30 minute long performance represents the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (bell hooks) by pointing to the layers of dominance, toxicity, and harm caused by whiteness and its many systems and mechanisms of oppression—present day and throughout history.

My friend who I came with is an Asian American woman of Korean descent. I would look over to her from time to time to see how she was interpreting the show, and what she might be feeling. We didn’t talk much at all during our visit, or even after. I did notice at certain points while moving through the gallery, her audible “uh-huh’s and mmhm’s”. Both of us have expressed how we process art better on our own before getting into conversation about it with others. I believe this to be true in this situation, and when art speaks directly to how you might identify, I find it a little challenging to talk about it with others who can’t identify or relate. I’m reminded though, in writing this essay, how important it is to go see art with your friends and to write about it. Ha! Even if you can’t talk about it with them, write about it. At least for me.

Later in the exhibition, there are three acrylic, medium-sized mirrors of different tints with masks made of porcelain. Titled Flawless, each piece sits alone on three separate walls. These reflections were points of question for me as the viewer. Looking into each mirror I see a mask that hides my face. The masks are shaped as sheet masks—a popular self-care routine in Asian culture. I was curious how the installer was able to line each piece to align with my eyes. How would viewing these mirrors at a different height alter how they are read? These pieces communicate a piece of Jennifer’s view on power, beauty, and perfection, as she says, “I hope when you look in the mirror everyday that you see the beauty and power you inherited from your ancestors.” As a third culture woman myself, I’m curious about the tools and practices outside of Jennifer’s artistic practice that brought her to this moment of affirmation, safety, and clarity for herself. How do we BIPOC artists today prioritize our healing? Where do we go to heal and grieve and become? Who do we go to to come back to ourselves? The fact that she is able to offer her moment of knowing with us tells me that there are deeper processes in place that may occur in her everyday practices and rituals. To be in a place of affirming a stranger’s power and beauty illuminates, for me, the power and beauty of the beholder—in this case, Jennifer Ling Datchuk and her ancestors.

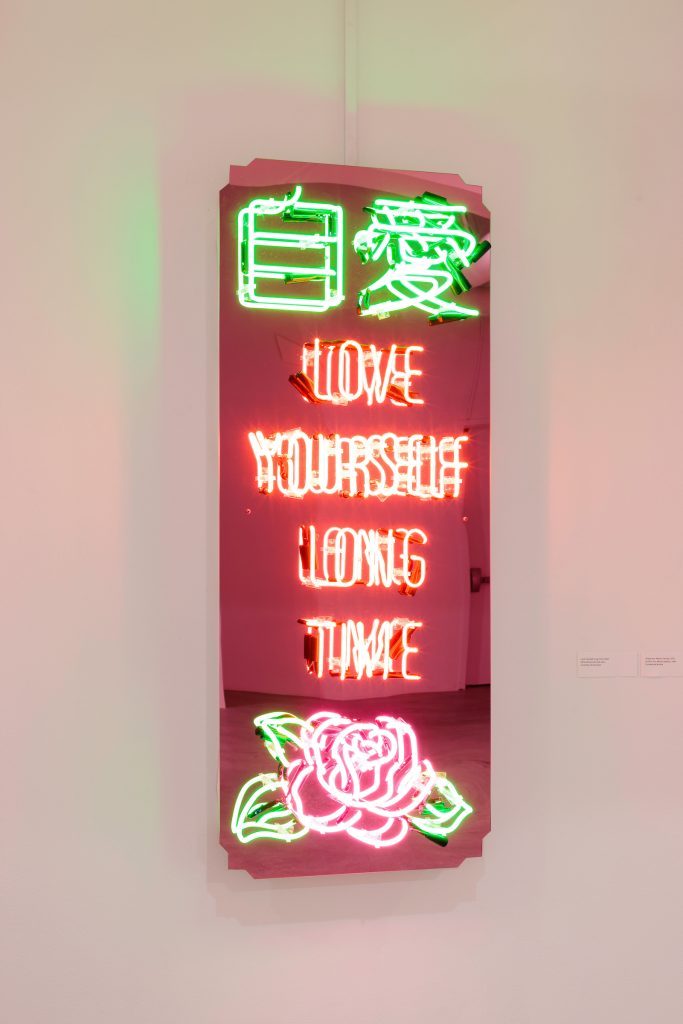

The subtitle of the show, eat bitterness: a Chinese idiom to describe enduring hardships without complaints, or even to suffer, reminds me of a survival mechanism known by myself and my BlPOC friends. Where we’ve learned to endure to survive, rather than resist, refuse, reclaim our space, and thrive. I do believe we are challenging and breaking this belief system from our understanding of being, and doing our best to live lives where we are co-creating what we know and want for ourselves and our loved ones, and fighting for our needs to be met, everyday. Jennifer does this by giving voice to the stories and narratives that have harmed her and the women in her family; chosen and blood-line. She captures this notion of reclamation, undoing, and unlearning concretely in many moments throughout the show. I felt these sentiments while engaging with her piece, Love Yourself Long Time, a three-foot acrylic mirror, with neon signage hangs in the center of the wall. The neon green text at the top of the mirror is in Chinese. Right below reads the title of the piece translated into English, in neon red text. At the bottom of the mirror is a neon rose. In this piece, Jennifer reclaims her body from the objectification intended with the original phrase, “Me love you long time” first used in the 1987 film, Full Metal Jacket. Through her action of changing the narrative behind this phrase and creating a language that uplifts and supports her community, we are given the opportunity to witness an example of refusal and complaint rather than enduring suffering. We can undo what once harmed us.

As mentioned above, I met Jennifer’s work with grief and mourning in the worst way. Losing my mama, having lost Mom. The consistent themes and motifs working in her show were like an embodiment of many questions I’ve sat with for some time now—as a midwestern, Black femme-woman artist and organizer with Native/Indigenous South Pasifika roots: roles women continue to play (out of force, familiarity, tradition, nostalgia, survival, not knowing better—across ethnic lines, race/culture) in family and society, the sacrifices we make over a lifetime, traumas on the whole body; mind, body, and soul, and un-lived desires. How all of these social, cultural, and political biases and their consequences can break the body. Jennifer captures these questions and sentiments strongly in each room of Eat Bitterness. However, these questions came to a head with Hustler’s (my neck, my back series).

Three porcelain figures carry on their backs an array of pots, mandarins, and what appear to be the pits of plums. All figures have an open mouth except for one that has their tongue out. This feels like a lighter moment in the show, not only due to the tongue, but also because of the part of the title that is in parentheses. “My neck, My Back (Lick It)” is a song by Black American Rapper, Khia. This hit is all about pussy power, sensuality, demand, and femininity. It’s had many lives and recreations since its release in 2002. I’m curious about Jennifer’s desire to subliminally shout out pussy in this series and how else the erotic influences her and her work. But back to the figurines. The figurines seem to have an expression of delight on their faces, while being in a table-top position, carrying things on their back—a nod to how Asian women experience fetishization while also laboring and providing service, product, resource. Again, the question around a ‘breaking point’ comes up for me along with enduring hardships and suffering without complaints. Not only because of the weight of the objects being placed on the back of the figurine—‘backbreaking—but also because of the material Jennifer primarily works with: porcelain, an extremely fragile yet resilient material.

“I work with porcelain because of its discovery in Jingdezhen, China over 2,000 years ago. I also use it as a cultural connection to my Chinese heritage. When it was first discovered, it traveled all over the world and it was desired for its purity and whiteness. I use porcelain as a metaphor for the white desire I see throughout the world and whiteness as a desired, privileged racial class.”

Jennifer Ling Datchuk

Can this breaking point be a point of liberation, freedom, and release of what no longer serves us? Perhaps it can be a clearing for all that lives and becomes outside of tradition, outside of binary—broken open.

Jennifer Ling Datchuk: Eat Bitterness was on view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts from May 20 to September 18, 2023.

About the author: Mary Elizabeth Jo Dixen Pelenaise Kapi’olani Lawson is an artist and organizer currently based in the Midwest. Mary is interested in asking questions and living as beautifully, tenderly, slowly, kindly as possible. She loves the sun, friends, family and music that you can feel in the pit of your soul. Photo by Audrey Hertel.