This is the fourth and final article in a series about Body Passages, a partnership between Chicago Danztheatre Ensemble and The Chicago Poetry Center (the first, second, and third pieces can be found here). These articles provide brief looks into a 10-month, interdisciplinary creative process between Body Passages poets and dancers, documenting and reflecting on aspects of that process as it happens. Launched in 2017, Body Passages is an artist residency and performance series curated and produced by Sara Maslanka (Artistic Director of Chicago Danztheatre Ensemble) and Natasha Mijares (Reading Series Curator of The Chicago Poetry Center; Natasha also writes for Sixty).

Trigger warning: The performance “Blood Memory,” discussed below, contains references to sexual assault, including in childhood.

During a culminating event featuring groups’ final performances, the Body Passages artists offered the audience sugar cereal, sparkling cider, and glowsticks; invited us to dance with them and record ourselves reading their poetic curations; and asked us to travel back in time with them to New Year’s Eve 1998. Especially appropriate given Body Passages’ collaborative focus and this year’s theme of “activation,” much of each group’s performance indeed brought the audience along “with them,” as every piece invited interactivity as part of the performance and/or as part of its development. After a 10-month process of working together in interdisciplinary groups of poets and dancers — and periodically sharing drafts of their work with the public — at this event eight Body Passages artists presented four final pieces: “The Mother,” “I Am,” “Blood Memory,” and “Wax.” These multifaceted works engaged topics such as abortion and reproductive rights, sexual assault, childhood trauma, parenthood, personhood, identity, joy, fulfillment, influences, and the voices within (and those who may be out to silence them).

Having witnessed excerpts myself and also having heard the artists discuss these pieces over the last several months, I entered the space on the show’s first of two evenings — Friday, October 12 — both knowing and not knowing what would occur. I enjoyed seeing expected developments in the works as well as utter surprises and complete twists in tone.

What follows here is a narrative rendering of the culminating event, including glimpses of my experience and of my interpretations of its performances, along with reflections on the threads between them and the larger Body Passages program.

Upon entering the venue — the Chicago Danztheatre Ensemble auditorium, on the second floor of Ebenezer Lutheran Church — there appeared to be two shows in one, each informing the other. The long rectangular room was divided roughly in half, with an interactive installation area near the entrance (communicated by a “U” of tables) and a thrust-style performance space farther back (formed by a single row of chairs on three sides to create — with the stairs to the stage — a sizable square). Although the centerpiece of the event was the performances that were to take place in the rear space (during what I’ll call the second “act”), guests were encouraged to circulate toward the front for the first 15-20 minutes (act one), participating in activities at installations that had been created by the same artists.

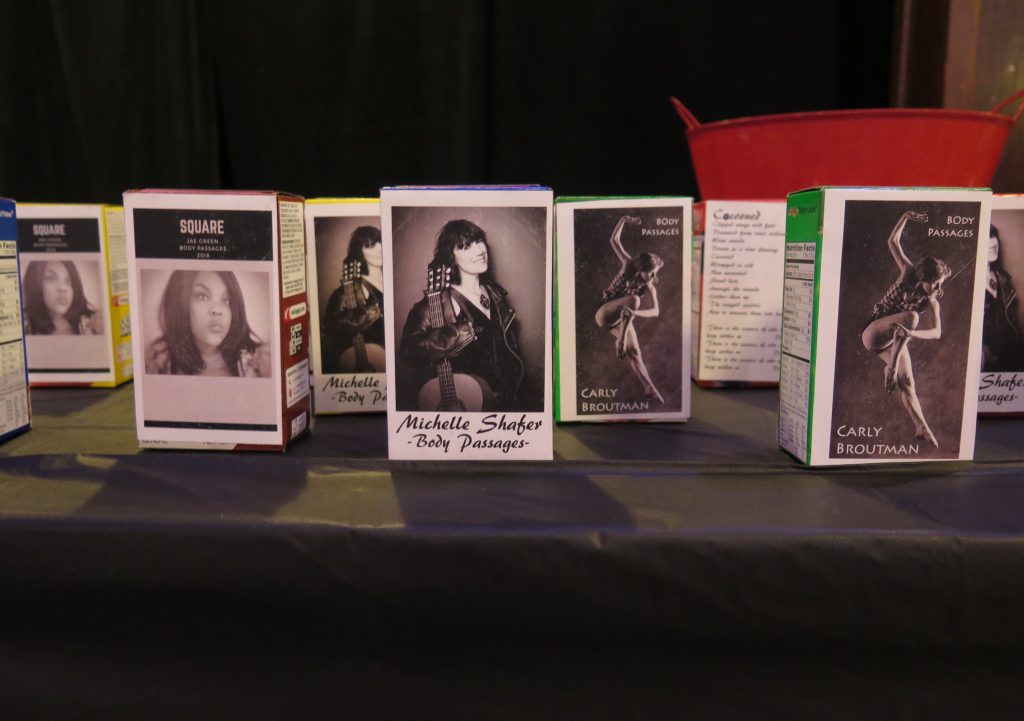

These installations referred, in varying degrees, to the performances to come in act two. One group’s station offered guests single-serving cereal boxes, each stickered on one side with a black-and-white photograph of a group member (Carly Broutman, Jeanette “Jae” Green, or Michelle Shafer, co-creators of the forthcoming performance “Wax”) and, on the other, with a poem, quote, or lyrics. (“Like Breakfast of Champions,” Michelle said after the show. “Women to look up to. You can be a dancer, you can be a songwriter, you can be an amazing poet.”) While athletes and other celebrities often grace such covers, it struck me as refreshing, even renegade, to put artists — and their work — on cereal boxes. A second table, related to the performance “I Am” (by “Maggie Robinson, Allison Sokolowski, and YOU”), invited guests to “Paint your nails and add some color to your life!” (with supplied materials) and/or “Grab a slip of rainbow paper and answer one of our primary questions: Who are you? Where have you been? Where are you going?” (priming the audience for the performance to follow). A third display — connected to Lani T. Montreal and Maxine Patronik’s “Blood Memory” — offered information from RAINN about sexual violence and publicized the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline (800.656.HOPE). Alongside sat a copy of Maxine’s undergraduate thesis paper, “Scattered Swirls: Understanding a Fragmented Past Through Embodied Knowing,” and a poster-size drawing of a tree, with leaves that guests could fill in to demand “SUPPORT BELIEVE ♡ SURVIVORS.” With these interactive installations, the mode of participation was not necessarily passive, but low-pressure, with guests receiving something or taking a small action but not having to share or generate something new.

“The Mother”

Also taking place in the front space during act one was “The Mother,” an interactive poetry gallery created by David Nekimken, now functioning as his own group. David’s installation stretched along a wall where three tall, black screens each designated a kind of step. A sign prompted, “Read/Speak/Move,” and a facilitator invited guests to begin their involvement in David’s piece by reading seven writings suspended on one of the screens: Gwendolyn Brooks’ “The Mother,” five “Golden Shovel” poems David wrote in response to Brooks’ poem, and “Secret of ‘67,” non-fiction prose from an anonymous individual. (In brief: Per Don Share, Golden Shovel is a poetic form created by Terrance Hayes “in homage to” Gwendolyn Brooks, wherein “the last words of each line…are, in order, words from a line or lines taken often, but not invariably, from a Brooks poem.”) On a nearby table lay copies of each of these and of three additional poems: Katie Heim’s “If My Vagina Was a Gun,” Abby Minor’s “Your Country and Everyone In It,” and Leyla Josephine’s “I Think She Was A She.” While and after reading the 10 offerings, participants were asked to consider “Which voice exemplifies personhood to you?” and then were invited to record themselves reading that piece on a provided tape recorder or video camera. (On this day, less than a week after Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, I picked Heim’s “If My Vagina Was a Gun.”) Finally, participants could accompany David, responding in movement to the 10 writings or to one of many prompts, each a short excerpt.

Throughout the first act, David danced in a spotlight in front of the largest screen, spinning around and swinging his arms and, at other moments, shuffling back and forth to simply keep the movement going. I shuffled around the floor with him as we informally discussed his piece and process. I asked David why he had chosen his topic — abortion, and sometimes reproductive rights more generally — and he answered, “I didn’t; it chose me. It just happened.” Of reading Brooks’ poem and creating his Golden Shovel poems in formal and thematic response, he said, “I really got into being in the mother’s shoes — as if I were the mother [in the Brooks’ poem] who had had those abortions,” a creative process he likened to a “journey.” In “stepping into” the poem and creating multiple poems stemming from it, he was “getting different voices,” exploring perspectives that were and were not his own, as well as the pressures and challenges that someone considering an abortion might face. Although David was completing the Body Passages program without his original partners, he found that “this subject matter really activated a number of the other performers,” asserting that the ongoing discussion with other Body Passages groups online and in meetings functioned as his piece’s “collaboration.” While some performers had very “particular” points of view about his initial poetic responses, he chose not to “step back” from the project but rather work to recognize those.

So, in addition to Brooks’ poem (which, during a mini-critique I attended in July, someone described as a poem “that both sides of the abortion debate have used to argue their side”) and his Golden Shovel poems (which he characterized as generally “pro-choice but recognizing that it’s a difficult choice”), David then decided to include “Secret of ‘67” (a personal story about getting an abortion before it was legal to do so, emailed to him by the friend of another artist) as well as the three other, more overtly “pro-choice” poems (all recommended by Body Passages co-director Natasha Mijares, on David’s request). He credited this “give-and-take” with the other artists as bringing his project to its current point. David reflected that his being male may have impacted his colleagues’ earlier reactions, but that the larger takeaway was that he needed more voices; it was not that he couldn’t include his own voice in the conversation, but that it couldn’t be the only or main one. He also realized he could integrate his own personal experience by writing a poem about a father. To me, a central concern of David’s piece and approach seemed to be that of begetting — in one respect, about the very notion of “choice” and consequences (however proffered, enabled, or limited); in another, how one artist’s work can inform or inspire others’ thought, or literally shape another artist’s work.

For the event’s second act, audience members moved to the area farther back by the stage in order to watch the performances “I Am,” “Blood Memory,” and “Wax,” which moved fluidly from one to the other, together occupying the better part of an hour.

“I Am”

Maggie Robinson and Allison Sokolowski began their performance “I Am” dancing onstage, then drifted to the floorspace closer to the audience, where they remained for most of the piece. To start, Maggie and Allison moved slowly and in unison, with slight differences as seemed appropriate given the content of the audio: collaged recordings of people they had interviewed, reflecting on what shapes one’s identity. This soundtrack was a highlight, with its interviewees — apparently of a range of ages and backgrounds — addressing various factors and intersections that impact who they are, including inherited traits, cultural influences, sexuality, gender, social constructs and conditions, personal choices, “everyone I’ve ever met,” and more. The interviewees also considered broader questions — in so doing, posing them to the audience, too. What does it mean to be a completely different person now than you were 10 or 20 years ago? Is identity always fluid? Is finding yourself more about comfort or discomfort? What are the ways our actions influence others — but also influence ourselves? As the soundtrack progressed, its focus narrowed from abstract musings to personal specifics. Interviewees shared what it means to be “authentically me” or “unapologetically myself,” then asserted aspects of those selves, from “I am quick to laugh” to “I am a hardass bitch.” Repeated throughout the soundtrack and the performers’ periodic live speech were the core questions from the installation up front (Who are you? Where have you been? Where are you going?), as well as other questions encouraging self-affirmation (What do you love about yourself?). The buoyant collage of sound functioned well, raising questions about what “identity” is, answering them partially and multiply and obliquely, thus — productively — refusing a single definition.

Amid this soundscape, the performers shifted between dancing in parallel (often holding each other or enabling each other’s movement) and responding differently to the same verbal cues (diverging instead of moving in unison). The performers shifted, too, between literalism and lyricism, and between more “theatrical” and “naturalistic” styles. At points, connections between the text and movement were overtly representational, with a word or stated idea seeming to serve as an analog for a movement phrase (e.g., shaking hands on “meet,” pointing while asking “where are you going?”). At other points, these connections were more felt (e.g., a contact-improv in which each performer’s taps suggested the other’s steps; a performer pushing their prone body across the floor, accumulating yarn while voices listed influential family members). Their choreography appeared mostly to comprise predetermined sequences, but also sets of rules, like moving in patterns to cover all the space.

Toward the end of “I Am,” Maggie and Allison returned to the stage proper, lingering as they ran their hands over what I had thought, from my distance, to be a suspended string of papel picado, but which a projection revealed to be post-its bearing handwritten notes (perhaps from an earlier iteration of their activity). Running toward the audience, they joyously threw sheets of colorful paper in the air like 8.5 x 11 confetti. As the performance concluded, it struck me that I had been waiting, unconsciously, for “I Am” to turn sour or cynical, but that never happened. I realized how rarely I experience an artwork that is so persistently optimistic while not eschewing real-world complexities — even, embracing them. Throughout, “I Am” felt both implicitly and explicitly inclusive. Before ending with a reiteration of the core questions, the soundtrack proclaimed, “You are enough.”

Of the performances in act two, “I Am” felt the most like an extension of its installation at the front of the room, with the table-top version priming for the performance, and the soundtrack prompting the audience to return to the former. While the “interactive” aspects of this group’s piece seemed largely to precede the culminating event (i.e., the interviews that became the soundtrack), this work most fully used the space, with Maggie and Allison traversing the entire performance area and gesturing frequently to audience members and the room we shared. In this way, and in its emphasis on self-reflection, “I Am” functioned nicely as an opening offering.

“Blood Memory”

Up next was Lani T. Montreal and Maxine Patronik’s “Blood Memory” (profiled at greater depth here, while in progress). Even knowing much of its content and form in advance, I found their performance thoroughly engrossing, even exquisite.

The piece opened in darkness with the sound of a heartbeat. As lights came up, Lani circled the floor, singing in Ilonggo, then settled on a stage step to tell the story of her birth, as told to her by her mother. Maxine began to dance onstage, her movement expanding, speeding up, and covering more ground as Lani listed her own feats of bravery: climbing trees and mountains, watching horror movies, walking through a warzone for a story. “I traveled 8,000 miles away from home, alone, to find my niche in the world,” Lani continued, then turned. “But the one thing I could not get over is my fear of men.” Maxine’s pace and quality of movement matched this shift from confidence to pause. Through flashes of anecdote, Lani created layers of complication — feeling drawn to men though terrified of them, reading studies that show fear can be genetically bred into succeeding generations of mice, hearing a self-harming woman’s realization that her parents’ and grandparents’ guilt, pain, and regrets are “braided into her DNA.” Lani’s speech was direct yet elliptical, engaging a story from her childhood in the Philippines about the scars the sun gave the moon (“he threw burning sand in her face”) as a parallel vehicle for conveying the emotional weight of trauma, even reflecting on uses of storytelling and the promises and failures of language itself. “There are tales — and there are truths.” Lani spoke in veiled but unambiguous language about a little girl steeling herself against groping and unwanted hands, amid “much merrymaking” in her own home. “In the morning, she cried and writhed in pain and shame she could not put into words.”

Lights dimmed as an audio collage played — beginnings of stories of sexual assault. Layered and interwoven, the accounts quickly became cacophonous, likewise preventing specific details from being audible. Maxine stood farther forward, leading with movements that Lani echoed after a few beats. This movement phrase repeated, with one dancer’s cycle overlapping the other’s, before transitioning into a semi-improvised pattern of contraction-and-release. The performers came together and, as the voices faded, Maxine helped Lani back toward the stage. This moment — and its sudden stillness before the next storm — marked a significant transition. Employing a different mode of address, Lani belted out “One out of three women, one out of three…,” in a descending line, ending with an extended “One.” The language in this section was more overt, too: A 16-year-old who was “almost raped. Almost killed. Almost gave up. Almost.” Lani delivered the story of that girl, “lured to a motel room with the promise of an audition,” who then, in her fear, “kept the story within her.” It became more personal: “But it lingered in her blood and leaped through mine.” As Lani reflected on how fear breeds silence, Maxine paced behind her, offering delicate, supportive touches. Lani’s insistence on the power of speech is worth quoting at length: “What matters is that we struggle against the silence — with words. Cut through, slice deep. Make known our protest. Because the silence is thick. What matters is that we prepare for battle. The idea is to intimidate the quiet. Clear the spaces where silence lurks in ambush. And then fill them! With resistance, but also with moments of joy.”

The recorded audio returned, with Lani’s live voice now adding to a list of what brings each speaker joy — such as books, diving into cool waters, and binging on Netflix. Maxine shifted from gestures of exuberance and wonder to stand at Lani’s side, helping Lani raise her arm up, hand formed in a fist, as Lani said, “We’ll raise a metaphorical fist against a panel of white men in black suits to make sure we are all safe.” (While this could refer to numerous incidents as well as a general condition, the image that first came to my mind in that moment was of the previous week’s testimony by Dr. Christine Blasey Ford.) The piece concluded with the earlier “one out of three” musical phrase, sung by Lani, Maxine, and, by their invitation, the audience. Lani declared, “We’ll survive.”

Lani and Maxine were polished performers, each possessing artful stage presence and captivating conviction. In a performance that was, by design, pared down (simple dresses, barefoot, no props), its success was chiefly reliant on the speech of one performer (direct, poetic language) and the movement of the other (controlled, fluid dance). Individually, they struck me as artists in command of their instruments and forms, capable of expressing deep pain or self-assertion not just through words and gestures, but by seemingly projecting those emotions from some well within their bodies. Throughout, the performers maintained, in the distance between them, a productive tension that lent dynamism to those changing expressions and emotions, enabling the few moments in which they did physically touch to spark with extra charge. The rare moments of unison felt similarly potent. While it wasn’t made known which subjects of the third-person stories, if any, were also the first-person performers (who, at points, allowed ambiguity between “the girl/woman” and “I”), the integrity with which those subjects were portrayed made them feel both very personal and like a collective narrative — a tension also present in “Wax,” the final performance of the night.

“Wax”

Perhaps of all of the performances, to me the one that most defied summary was “Wax,” by Carly Broutman, Jeanette “Jae” Green, and Michelle Shafer. Also the longest piece, its performative mode flowed between poem, game, song, dance, and even party (with Jae’s own daughter cameoing as “garçon,” handing out non-alcoholic cider to audience members). As with the group’s single-phrase description of “Wax” in the event program (“An exploration of the feminine creative self and the society we build and nurture to support it”), the piece’s spoken narrative — delivered mostly by Jae — was simultaneously plainspoken and enigmatic, with every mark of presence drawing attention to an absence.

The piece began in silence, with Carly alone on stage, seated cross-legged then dancing low, before walking down to the floor where Jae and Michelle met her. The three women briefly competed, jostling for position closest to the audience, then playing rock-paper-scissors to determine who would share first. From there, each woman’s story claimed its portion of the performance: Jae’s then Michelle’s then Carly’s. (Characters referred to each other by the performers’ names so I’ll do the same — though, importantly, any autobiographical seeds here were likely interlaced with creative liberties and otherwise complicated.)

Moving closer to the audience, Jae offered “Smoke,” a poem about the birth of an artist by an artist — specifically, Jae and her father. With his image projected behind her, Jae remembered her own awe of him, the beauty he saw in the world and in her, and the moment when, at age 4, they both realized she, too, was an artist. She recounted the lit match in her father’s hand and “watching the air marble around me” as “my final eye” opened — with it, an awakening awareness of a special kind of sight for which she didn’t yet have words besides “Daddy, there are stories hiding inside of the smoke.” From here, Jae served as the narrator and emcee for “Wax,” providing context and voiceover for the subsequent scenes, in which Michelle played guitar and sang and Carly danced. Throughout, Jae’s voice was confident, smooth, and unrushed, even as her narration turned swiftly, allowing humor and gravity to collide and co-exist.

In introducing Michelle’s section, Jae welcomed the audience to a New Year’s Eve party on the cusp of 1999, which she contextualized as before Columbine and 9-11 and before people used Google, as well as when Michelle would drop her next album. Carly danced, exploring and twisting, as Michelle performed her song “10,000 Hail Marys” (which, in actuality, is from her 2016 album “Grey Area,” but Michelle noted post-show it “just happened to fit” here). The live song was resonant and moody, with quick chords and dirty fuzz accompanying Michelle’s vocals: “Too much passion onward fleeting.” At a pause in the lyrics, Jae described a man who met Michelle that night and later bragged to his friends, “She’s an artist.” This unnamed man was compelled by Michelle even as he was confounded. “Dating her is like reading a book with every seventh page torn away,” Jae told us. “Girls like her, they don’t marry guys like him! But they do.” And, with that, Michelle’s life changed. “Soon enough, she’s not painting — but his shirts are perfect white crisp cardboards. She’s not sculpting, but her mashed potatoes are a Platonic alchemy.” Michelle’s electric guitar angered and Carly lunged and spun. Jae detailed what the couple does and doesn’t enable in each other: Michelle finding she has given up her art to be a wife and a mother; the husband not minding infidelity as long as she plays her part at parties. “It’s enough that she married him” — until it isn’t. Jae transformed into the husband, challenging Carly, suddenly the wife, and threatening to take their children. Michelle’s lyrics chimed in: “10,000 Hail Marys keep those thoughts at bay.”

Image: This is a link to Michelle Shafer’s song “10,000 Hail Marys” (from the album “Grey Area”) on SoundCloud, with a black-and-white photograph of the musician in the background and a graphic running horizontally along the bottom of the image to show the track’s progress. In the photograph, Michelle stands in relative profile, looking toward the camera, though she is only visible from nose to hips. She wears a dark, shiny tank-top and light bottoms, and holds an acoustic guitar over her shoulder.

There was a subtle distance throughout Jae’s narration here, not saying “her friends,” but “the women that she calls her friends.” While never suggesting that nothing was gained, there was a sense of mourning — open, unapologetic — for what was lost or even taken. These “women she calls her friends” share scars from C-sections, plastic surgeries: “The thin lines that they have between love, life, and death. There will be no place to show, no place to point, the place where she once was. But sometimes, she remembers the dance.”

And, with an audience countdown, the New Year came and went.

After Jae served the whole piece as narrator, Carly’s voice was startling. Her spoken phrases were terse, labored, punctuating her movements as she pulled herself off the floor before falling again: “Stop. It’s over. Everything is over.… I can keep going, but the reminders of my body are honest. They tell me what I’ve done…. The marks stay. They do.” In the piece’s last, powerful stretch, Michelle strummed her sparer, acoustic “Fragile Answer” (written for “Wax”) as Carly whipped her weight around the space. Carly — the dancer employing the most overt athletics of the evening — used the stairs notably well, stretching her body upside-down between floor and stage, sliding over the steps to nestle Michelle and her guitar. “Wax” ended as it began, with Carly cross-legged in silence, but this time on the floor close to the audience.

Having so many shifting modes and moods and strong personalities onstage at one time risks fragmentation of the audience’s attention or orientation, but the “Wax” group gelled well, augmenting each other’s stories with surprises and contradictions, especially the contradictions between them. There were moments where it felt like the three women were performing in unison (even as they were, in fact, saying and doing different things) and moments where there was a productive schism between their actions: Carly’s movements neither literally illustrating Jae’s words or dancing “to” Michelle’s songs, Jae’s spoken words neither providing lyrics to Michelle’s melodies or narrativizing Carly’s gestures, and Michelle’s music not merely setting tone but infiltrating the scene and moving it along. And, impressively, all of that worked. I was very taken with this trio and how they coexisted onstage — as if there were elastic strings connecting the three players, granting each room to express while constraining them in the same triangulating orbit, such that who was pulling/following/supporting/holding the other two in equilibrium remained both invisible and dynamic throughout the piece. As I watched, I found myself looking for something present that was, at the same time, not in front of me, but that instead had to be intuited — often in these gaps.

This piece also marked the sharpest differences between the tone I expected to find in the final performance and what I actually experienced. From an excerpt I’d seen at a mini-critique, I thought it would be funny, even goofy or giggly in spirit. “Wax” was, in its way, all of those things, but it also reflected great pain, pride, self-assertion, and loss. It depicted how choices and chance encounters beget other consequences and decisions and risks — in this piece’s framing, especially when you’re a woman or an artist, and especially especially when you’re a woman and an artist. Afterward, I overheard several women go to Jae and Michelle to share how the romantic relationship shown in “Wax” resonated with their own lives, reminding them of men they knew who tried to “control creative women” or “blow out their light,” even as that creativity is what had drawn the men in (a situation that doesn’t have to be gendered as such but in this conversation was); I myself felt a similar resonance. Unstated but present in “Wax” — and in all of the evening’s performances — was an underlying concern with what it means to be in a physical body and to pass through time and place in that body.

Across these performances, I also had a powerful experience of the venue itself. Particularly in thrust set-up, the space facilitated fluidity in and between the performances, allowing for easy movement between stage, steps, performance floor, and audience, as well as for varied disciplinary and thematic usages. From that initial theme of “activation,” the four Body Passages groups had branched widely, ultimately exploring issues ranging from reproductive rights to cultural and gender diversity, to healing from sexual trauma, to what different individuals need to claim for themselves in order to be themselves. The collective framework seemed to be one of radical inclusivity, representing and celebrating an expanse of identities and values. As a person raised Catholic (despite my own differing beliefs), to me it felt continuously, delightfully striking to hear such inclusivity expressed while sitting in a “church” space — a setting I suddenly remembered in the pause between each performance, before being drawn back in, to each subsequent piece.

Something I’ve certainly valued about Body Passages as a program has been its openness; for instance, through its Chicago Cultural Center residency and various “in-progress” events. In my experience it’s relatively uncommon for members of the public to have such access to artists’ creative process, to be not only a fly on the wall but even a player in shared space as new work is being drafted and troubleshot. On this evening, it was especially satisfying to see works in their final form that I’d witnessed glimpses of in previous months, a pleasure akin to seeing something grow up. By that same token, it was disappointing how many other works with equally promising conceits didn’t make it to this phase (at least, not as part of Body Passages; several more people began the process than ended it, seemingly for all the reasons that that happens).

Similarly, throughout my experiences with the Body Passages groups, including at events and meetings not covered in this series’ writings, I admired the generosity at the root of their collaborative process as well as the intimacy and respect that appeared to have developed between the artists, even as they didn’t always agree with each other’s perspectives or tastes. While such conflicts seem endemic (often productively) to any partnership, it feels important to acknowledge that this program intentionally fosters such exchange by design — curating artists of different disciplines into groups, before facilitating them through the long-term process of co-development and experimentation outside of their purported comfort zones. As Natasha Mijares noted in an earlier article: “People benefit from being pushed by others in directions that you wouldn’t go [if] sitting by yourself in a room.” By the conclusion of the 10-month program, the eight remaining artists had challenged themselves to take on new skill-sets, taught each other aspects of their own gifts, and together questioned and responded to the contemporary world.

Indeed, the groups’ works addressed issues that, by the day of the show, felt especially timely to broader national conversations, by some combination of persistent relevance, prescience, and chance. “Blood Memory,” in particular, seemed to be living in that space between the stage and the world; as an experience, it felt both urgent and enduring, urgent in its endurance. But all of the works possessed this thickness — an insistence on reflecting, making experiences visible, and paying attention. In all, and perhaps consistent with Body Passages’ intentions, the most compelling moments for me were those in which language and movement not only complemented but also complicated each other, evidencing gaps rather than filling them — suggesting that the deeper you dig, or even the closer you grow, the more reveals itself to still be unknown.

Featured image: Maggie Robinson and Allison Sokolowski performing in “I Am” at the Chicago Danztheatre Auditorium, as part of the Body Passages culminating event. Maggie balances with one foot, knee, and hand on the floor, as Allison stands on Maggie’s lower back. The performers hold each other’s left hands and look at each other. Both are barefoot and wear white t-shirts and jeans. Behind them is a well-lit stage, with a string of colorful paper suspended across it. Still from a video by John Borowski.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)