Regarding the state of Indiana, I would say that it benefits from the perception crafted in our history classes that racism only exists in the south, and the northern states have always been a bastion of acceptance. Let me disabuse you of that belief. I went to college in Muncie, Indiana, where one of my professors quipped that Indiana is “the northernmost southern state.” In 1843, famous abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass gave a speech in Pendleton, Indiana and was nearly bludgeoned to death by a white mob of anti-abolitionists. Additionally, Indiana has historically been a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity, (a fact that was shared with me repeatedly, almost gleefully during the time I lived there) and Confederate flags are the norm. Anecdotally I’ve seen them on car bumpers, proudly displayed on front porches, sewn onto jackets as patches, and on the wall of a frat house, just to name a few. All of this matters because The Davis Lab at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) at Newfields is currently hosting an exhibition of Thornton Dial’s piece Don’t Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got to Tie Us Together. I saw it over Mother’s Day weekend and I have a lot of thoughts.

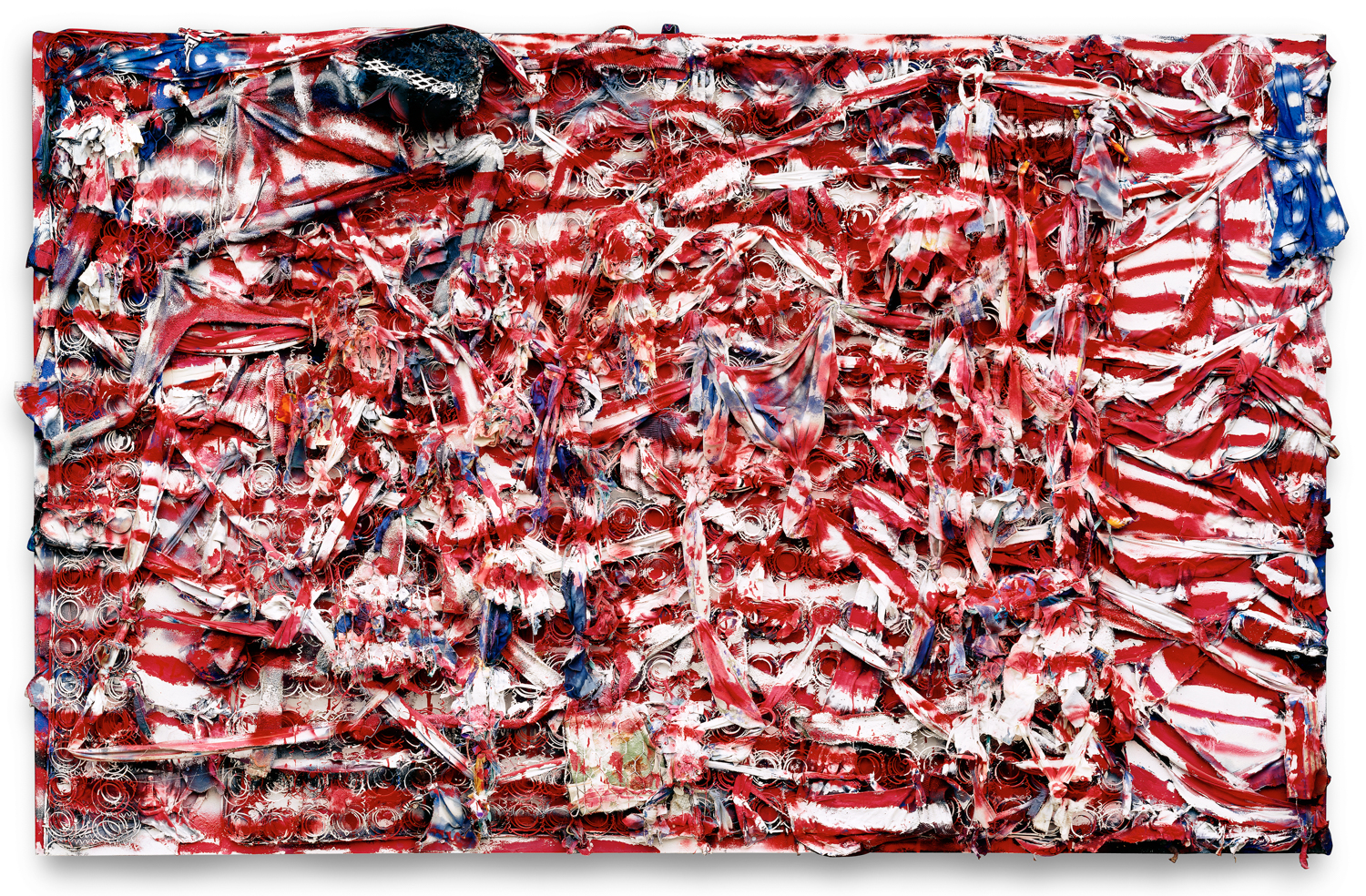

In what I assume is a response to the growing mainstream acceptance of Black Lives Matter and the modern civil rights movements, the IMA is illuminating this piece from Black artist Thornton Dial. To some people, I imagine that Dial represents the kind of classic American story of bootstrapping and capitalistic ladder climbing. Born to a teen mother on a sharecropping farm in Alabama, the cards were stacked heavily against him. In a wild oversimplification of his life, he worked hard, persevered, and eventually became an established artist. His most notable works are comprised of found objects that he used to touch on complex subjects like American history, civil rights, and politics. On display at the IMA is his 2003 work Don’t Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got to Tie Us Together. The work is framed by the doorway of the small gallery and it’s an astonishing piece. The red and white American flag motif painted over layers and layers of shredded assemblage leap out at the viewer. It’s a haunting work that isn’t a feel-good piece of art but one that’s visceral and challenging. The assembled piece is made up of torn and discarded objects compiled together in one dense and layered work. According to the IMA’s website, “This installation is the first in a series of experimental displays designed to learn from our guests”. The vinyl on the wall of the gallery invites viewers to write how the work of art makes them feel. Dial’s piece is flanked by walls covered with handwritten note cards in response.

A few people came into the exhibition while I was there and they were noticeably drawn more to the cards and less so to Thornton’s actual work. And there were quite a few cards to see; there were lots of doodles from children and brief notes on unity or democracy from older folks. According to the messages, people look at Dial’s work and they’re sad or scared or worried. There were a few patronizing cards that said we should “stop complaining” or “smile more” and other annoying things like that. But what really irked me was the single note card that said “All Lives Matter.” On the website, the IMA explains their rationale for the selection of hanging the cards, saying, “We displayed nearly all of the responses submitted, excluding those that promoted hate or violence or had excessive profanity.” The conversation on why “All Lives Matter” is problematic and how it exists only as a counter-response to Black Lives Matter has been had countless times on the internet and I won’t rehash it here. So I have to ask the IMA, what is the value of displaying this card alongside the work of a Black man who was born literally during the Jim Crow era South? Posting a note with a statement that only exists to invalidate the movement for Black lives was either done deliberately, which is abhorrent, or in plain ignorance. And if it’s ignorance it flies in the face of the premise of the exhibition, which literally says on the wall that they are “listening”. Who is the IMA listening to? I’m pretty sure it’s not Black people, because if it was they wouldn’t have posted the card. As an aside, the IMA is the same museum that just last year posted a job opportunity that was seeking someone who could appeal to their core white audience.

“We’re listening”, the IMA proclaims on the wall before entering the gallery. Let me take this opportunity to issue another correction: listening right now isn’t good enough, a willingness to listen is the absolute minimum that anyone can do. Black people have been speaking, writing, and protesting for years. Everyone should have been listening decades, centuries ago. Now is the time to confront what happened (and is happening) during all of that time instead of listening. Everyone–museums, galleries, and other institutions–needs to ask themselves uncomfortable questions. Have our actions been harmful? How have those actions bolstered white supremacy and led to the current problems we’re facing today? What are we doing now to rectify or change that? The IMA fails to ask itself or anyone any hard questions, choosing instead to talk in general about feelings.

Through no fault of Thornton Dial, this exhibition is framed in a way that perpetuates the type of wishful thinking that allows people to believe that all it takes to overcome racism is unity beneath this flag. It takes the name of the piece and, instead of analyzing it further and working through the dense layers of shredded assemblage, it chooses to take it in the easiest, simplest direction. Whenever there is an enemy at the gates, we’re asked as patriots and Americans to put aside our differences and focus on the common threat: wars, acts of terrorism, environmental disasters. Black people are often encouraged to put aside our fight for equality and unite under the flag in times of crisis. Right now we’re absolutely in a crisis, but this time the enemy isn’t at the gates, it is inside with us. There is no foreign nation seeking to tear us apart, we’re doing it ourselves. We are tied together under this flag for better or for worse. But that does not mean that anyone can ask the oppressed to put aside their grievances to achieve peace with their oppressors. It will take real, hard work to overcome the years of marginalization and brutalization that have resulted in the racism that runs through this country like the blood in our veins.

The IMA is an institution with a far reach. In an act of cowardice or ineptitude (I can’t decide which and neither would surprise me), they avoid taking concrete action, choosing instead to prop a Black man’s work up and invite people to unload on it, good, bad, or ugly. I’m not addressing ways that the IMA could have presented this exhibition better because this review isn’t a teachable moment. I’m not an educator and I have no obligation to teach any white people anything. But museums, on the other hand, are places of learning. That’s their function. It’s why elementary schools take field trips to museums, it’s why there are docents and audio tours and literal directors of education. It’s the IMA’s job to be informed and educate those that walk its halls. But here they failed. Instead, they offered lukewarm representation in place of actually sending a message that would benefit the communities they serve both Black and white. For all the work that went into crafting an installation that supposedly “learns” from its guests, the result turned out to be a slightly better-moderated bathroom wall. Black artists deserve better.

I had originally planned to abstain from leaving a comment card, but I was incensed and frankly unable to keep my anger to myself. In a furious chicken scrawl, I wrote:

I feel like this was a missed opportunity. Instead of educating, this exhibition puts the onus on the art to do the work. There are so many people who see what they want to see, which is the beauty of art. But certain things like racism and discrimination are not open to interpretation. Thornton Dials’ work deserves more than to be a talking point for people who refuse to see his struggle.

Side 2

Do Better Next Time

– – –

Featured image: Don’t Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got to Tie Us Together by Thornton Dial. A large, mixed-media piece that looks like a tattered American Flag. © Estate of Thornton Dial. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio/

Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is an arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago, IL.