This interview is the second in a series with each of the current fellows at the Emerging Curator’s Institute (ECI), a Twin Cities-based organization that supports emerging curators through a year-long fellowship program that incorporates mentorship-based learning, professional development, and financial support. ECI is the first organization of its kind in the Twin Cities region and provides curatorial opportunities to Minnesota-based curators that are otherwise hard to come by. ECI supports four curators each year and is currently in its second fellowship cycle. Operating within the Minnesota arts community, ECI connects its fellows with local curators, galleries, artists, and other field professionals who support in the development and production of an exhibition or curatorial project. This interview is with Juleana Enright, an Indigenous queer writer, curator, and DJ living in Minneapolis. Click here to view the other interviews in this series.

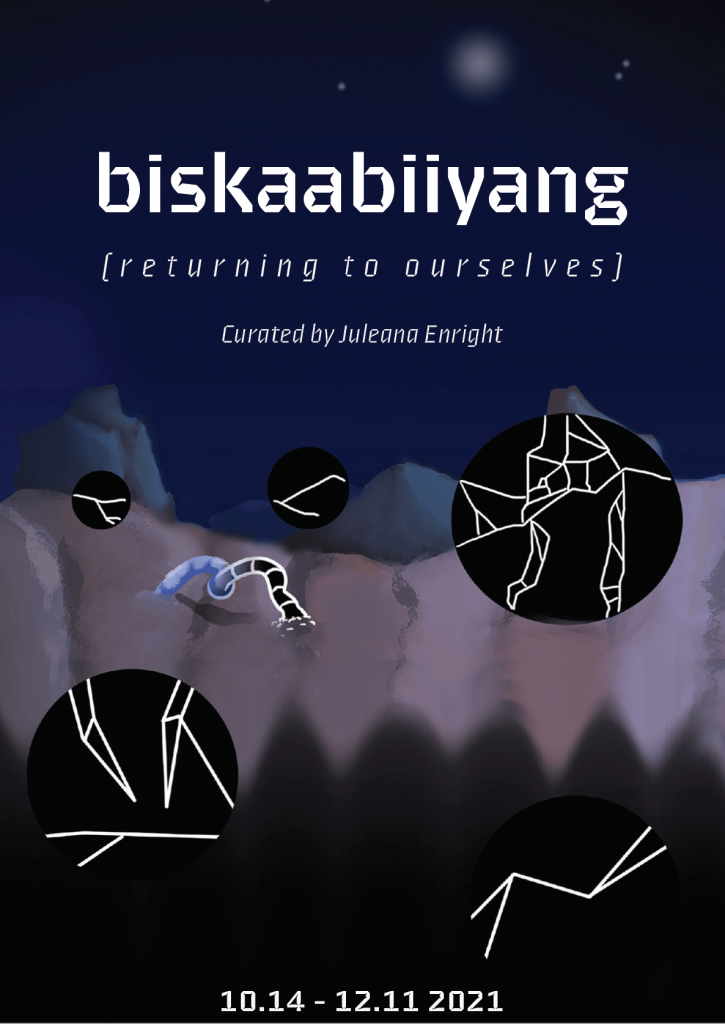

My conversation with Juleana was fascinating, containing innumerable insights that I have continued to ruminate and reflect on in the weeks following our interview. They speak about curation as a process that is grounded in collaboration, community, and consensual reciprocity, and emphasize the importance of enacting care within a curatorial practice. Juleana situates their exhibition within the traditions and practices of Indigenous Futurism, which they define in their catalogue essay as: “a correlative to Afrofuturism, Indigenous Futurism is a reclamation of Indigenous sovereignty, a transcendence of past, present, and future, imagining a world where colonization hasn’t threatened the civilization of Indigenous people and the representation of Indigenous people hasn’t been skewed in favor of the colonial project.” A culmination of their fellowship year, Juleana’s exhibition biskaabiiyang brings together six artists—Santo Aveiro-Ojeda, Sequoia Hauck, Reyna Hernandez, Elizabeth LaPensée, Coyote Park, and Summer-Harmony Twenish—whose work challenges colonial narratives and explores speculative futures that emphasize Indigenous sovereignty and survivance.

biskaabiiyang was on view at All My Relations Gallery in Minneapolis until mid-December 2021.

Ian Hanesworth: Can you tell me a little about yourself and your background in art and/or curation? I’m curious what practices or experiences led you to where you are now.

Juleana Enright: I kind of fell into a lot of different careers and ventures throughout the last decade. When I moved here I was going to the University of Minnesota and I wanted to do journalism, but really quickly I found that that was not the route I wanted to take. At the time, in the early 2000s, journalism was really about the formality of everything and I was more interested in the ways fiction and non-fiction can coexist. So, I changed programs, and then dropped out of college later on, and started writing for a magazine here in Minneapolis called l’étoile, which was an arts, culture, and fashion magazine. I was writing for a good chunk of time, just doing art reviews and fashion reviews (which I was not good at, haha), and just immersing myself in the Minneapolis scene. Then I got a job as a communications specialist at Gamut Gallery, which is a fem-owned commercial gallery in the Elliot Park neighborhood of Minneapolis. From there, I curated my first show which was called The Second Sex. It was a cool little feminist show with some local artists, as well as Judy Chicago and a couple pieces of mine. I co-curated the show with Gamut’s arts director at the time, Jade Patrick, and another curator, Genie Castro. I loved doing it and the show was beautiful, but I also saw some gaps. I think when you look through the lens of feminism, there’s a tendency to gloss over that other identities and non-white voices exist within that umbrella. I wanted to do my own show, so, two years later, I curated an exhibition called Soft Boundaries. It was a show on how the vulnerable narrative can be used as a form of radical resistance and healing. After this exhibition I took a break from the gallery world and started doing my own shows. I co-curated a queer dance and performance night called Feelsworldwide with my friend Dom Laba, who’s also a local photographer. I was really interested in the curation of live events. There’s something about the energy of community in live events that’s really cool. And then I circled back into art curatorial practice. A lot of cool opportunities landed in my lap, some I worked for and some I was just fortunate enough to know a really amazing network of creative people here.

IH: It sounds like you’ve moved through a lot of different roles and opportunities within or adjacent to the field of curation, and now you’re currently a fellow at the Emerging Curator’s Institute. How has this fellowship shaped your practice over the last year?

JE: That program is wonderful; it’s everything. The mentors that we get paired with and the people directing the program are so supportive. We often joke that they’re our parents. They’re constantly looking out for us and they’re always there to take a phone call or answer any questions. Having someone in your corner like that, who knows what you’ve gone through, can help fix everything from little problems you have going on to huge issues. There’s nothing comparable to that kind of resource and support. And to have the other fellows going through the exact same thing you’re going through, to make an exhibition come to fruition, there’s a comradery there, and we can also depend on each other. It’s also just so inspiring to see the other fellows and what they’re interested in and what they’re doing. It’s a really spectacular cohort.

IH: How has the pandemic shifted or altered your course throughout this fellowship year?

JE: It was a complete 360 for me. I was working as a bartender and I loved my job, but I was working full-time at a restaurant. Then the pandemic hit and I was furloughed. I had the opportunity to go back but I was still concerned for the safety of my roommate and my parents, so I chose not to. I spent that time applying for grants and assistance, trying to figure out how I could make art be the focus of what I’m doing, and not the other way around. Now I’m doing art full-time and it’s wild to be able to have my work aligned with my ethics, and aligned with my passions. There’s that old trope “love what you do and never work a day in your life” and there’s something to be said about that. Obviously, work is work and a job can get stressful but I truly love what I’m doing right now. The pandemic sucked, and it still sucks, and it’s horrible for people who have lost loved ones, but I also feel like there was this switch in a lot of people’s mindsets of reconsidering what wasn’t serving them, and taking some time to refresh, and refresh again, and see what is it you want to be devoting your time and energy to.

IH: I’m so glad to hear that the pandemic for you has kind of been a catalyst for seeking meaningful change, and sort of a restructuring. It’s been that way for me too in some ways. In a previous conversation, you said: “curation can be a lonely process.” I’m curious if the ECI fellowship program provided a sense of community in the field or if loneliness might be an essential and generative part of the practice of curation?

JE: I don’t exactly know where I was coming from when I said this… I think maybe I was having one of those days haha, but I think I was coming from the concept of planning, how that can be a lonely process. When it comes down to it I really believe that curation is community, and it is collaboration. I really love what the Anishinaabekwe curator Adrienne Huard says about enacting care in your curatorial practice. It goes against this individualist approach and is able to add a multitude of voices to the conversation. You can practice this kinship and consensual reciprocity that I think is a beautiful part of the curation process. I would say that, for me, curating is unearthing what already exists, and creating space for what can exist.

IH: The name of your exhibition, biskaabiiyang, is an Anishinaabeg word that means “the enactment of returning to ourselves”. Can you tell me how you chose this title and how it encompasses the themes of the exhibition?

JE: A huge part of the inspiration for this exhibition was Grace Dillon’s Walking the Clouds, which is an anthology of Indigenous science fiction. When I got that book, things started really falling into place as far as what I wanted this exhibition to be about. I was already interested in Indigenous Futurisms. I had curated a series of essays for MnArtists in 2020 on Indigenous Futurisms which led me down this huge rabbit hole. When I was reading Walking the Clouds, there was this word that Grace Dillon mentioned, “biskaabiiyang,” which is the framework for reenacting a sense of sovereignty over land, over body, over identity, and harnessing the ancestral ways of knowing into the current state of self. I kept looking for it in Lakota because that’s my native language but I couldn’t really find anything that specifically matched up in the same way. To me I thought it was a beautiful word, I love the way it rolls off the tongue, and it really encompasses so many different aspects and ideas. When I was talking to my artists in the show, I think they were all thinking about this word and this concept in different aspects, and it was like a lightbulb went off in my head.

IH: How has your practice been influenced by the literary tradition of Indigenous Futurisms? How does the exhibition fit within or expand upon this tradition?

JE: I’ve always been really interested in sci-fi, but in mainstream and Western sci-fi there’s this sense of alien and otherness, and the people who have been displaced have been left out of that conversation. What I’ve found really interesting about Indigenous Futurisms – or Indigenous sci-fi on a literary level – is that it creates a different, anti-colonial narrative which brings different voices back into the conversation, voices that always did exist but have been left out. There’s an Indigenous comic artist, Darcy Little Badger, who in interviews has talked about not seeing herself in these kinds of bodies of work – in literary, media or comics – and creating these Indigenous comics to allow people to see identities, representations of themselves, that weren’t there before.

IH: How did you go about selecting artists for this exhibition?

JE: It was kind of random, in a lot of ways. It was a very chaotic way of them coming to me through the spiritual world or me coming to them, but I like to think that there’s beauty in chaos. I was in LA with a friend this summer and saw a mural, and thought it was amazing and immediately had to know who was involved. Coyote Park was one of them. I followed them on Instagram and hit them up and was like “hey, this is what I’m interested in, does this align with you?”. His work with his series “All Kin is Blood Kin” – photographing spaces of comfort, togetherness, and liberation – particularly led me down a thought process of harnessing the power of community towards healing. Summer-Harmony Twenish was another person who I was following on Instagram, and they were probably the first person I thought of for this show, specifically for their vivid, visual representations of body and sexual sovereignty for Two-Spirit, Indigenous Trans, Indigiqueer, and gender non-conforming folks. Reyna Hernandez has worked with All My Relations before, as part of their annual Bring Her Home show, which focuses on missing and murdered Indigenous women. I really adored her work, and especially the way she investigates the reclamation of the female body away from the colonial gaze. Sequoia Hauck is a local filmmaker, performance and theatre artist and I was drawn to their work on decolonization as an art practice and also the narratives in their work of community-based continuation and resiliency. Elizabeth LaPensée is someone I respect. I found an article discussing her interactive video art, and how she uses those works as an educational tool. She also edits an Indigenous comics collection called Moonshot and is the daughter of Grace Dillon, which – to me – brought the exhibition full-circle. Elizabeth was really interested in connecting me with some younger Indigenous artists who were investigating technology and video games as an art medium and that’s how I connected with Santo Aveiro-Ojeda.

IH: How is queerness entangled within the complex and multi-layered stories of these works and the artists that created them?

JE: I can’t specifically speak for the other artists’ journey, but when I was younger I felt like I was wrapped up in this idea of not being enough, not queer enough, not Native enough. As I get older, I realize that the stories I tell through my artistic practice are Native, are queer, because I am, and the personal is political. You can tell a story without being implicit, and you can be implicit without telling a story. I think Indigenous people and queer people are natural storytellers because, classically, our stories have been left out of the narrative. When you’re thinking about sci-fi on a mainstream context, I see this very intentional connection to both identities: Indigenous and queer. The intersection is that both identities have experienced erasure, and that futures for us aren’t supposed to exist; our futures haven’t been reflected in the context of mainstream science fiction. In doing that, I think they miss this crucial element of inclusion. For Indigenous queer (Indigiqueer) folk, the invisibility cloak is even more pronounced. When you think about being able to control and challenge and create the narrative, to be part of a world that adds queerness and indigeneity back into the picture, it creates a more authentic link to past, present, and trickles into the reality of the future. It all circles back to representation, and I think the artists who identify as queer in this exhibition are telling truths of their personal experiences and perspective.

IH: Do you think this exhibition is an exercise or practice of lifting that veil of invisibility, of creating the space for the representation that has been absent?

JE: Secretly, in a selfish desire way, I wanted this exhibition to focus on highlighting, representing, and uplifting Indigenous queer people, but that focus on identity was never explicit. I think that you can tell a queer story without being like, “THIS IS QUEER!”. I didn’t want to say that this is a queer exhibition, because not all the artists identify as queer, but I wanted to provide space and have the artists talk about whatever stories, or perspective or experience they have. I just let their work and their artist statements speak for themselves, and what transpired is a beautiful display of representation on the artists’ terms.

IH: One of the recurrent themes in this exhibition is time. In your catalogue essay for the show, you write about ideas of “Indian time”, the slipstream, the tensions between past, present, and future. How do the works in this exhibition engage with or complicate Western notions of time?

JE: Indian time is something that always makes me laugh. As a kid, it was my mom’s side of the family’s excuse for being late, that they’re running on Indian time. In the quote I use in my catalogue essay, Sherman Alexie writes about the past being a skeleton that is walking behind and the future is walking in front of you, and you exist in the middle. This quote really stuck with me when I was thinking about this exhibition and made me take a deeper look into the concept of “Indian time.” With Western conceptions of time, there’s this element of living in the present and thinking really hard about the future. I think that you can do that while also acknowledging what came before you, there’s historical trauma but there’s also ancestral knowledge. I think that it’s not just linear; it’s all in conversation with itself. In Indigenous and Native cultures, the people who have passed aren’t necessarily seen as being behind us. They could be in front of us, they could be right beside us. When I was having conversations with these artists, they were very much already thinking about these same concepts – how the past can influence what’s going on now, and how we can use both of these things to create an imagined future, the future that should be here, the future we want, the future that includes all the identities that have been erased. What I love about Coyote Park’s practice is that they’re doing a lot of work with land stewardship projects. When you have a conversation about land back, it sounds like something that is in the past and it needs to be brought back here, to the present, but it’s actually a larger conversation about what happened to get us to this point, what we do to make sure this doesn’t happen again, how protection of the land translates into sovereignty.

IH: I love the way you talk about time and linearity, and you touched on spirals, the way history can repeat itself, how we experience historical and cultural amnesia. I love how you think of ancestors as ahead or beside us rather than behind. That’s a really powerful way to think about it.

JE: There’s a Western or colonial mindset that forgetting what happened in the past, or getting over it, is the way we move forward. Like you said, historical amnesia is real. It’s a byproduct of colonialism. But guilt doesn’t move people forward. It’s only when we start having real conversations about responsibility, reparations and access that we can start to heal, to make systemic change, which can lead us into a more utopian future.

IH: There are threads of speculative and science fiction throughout this exhibition and throughout our conversation: the intermingling of innumerable futures and the reality of a present-day Native-apocalypse. Within the genre of speculative fiction, world-building is often paramount, and in your essay, you write about “sovereignty as a practice of world-building, [of] queer and Native utopia-building”. I’m curious if you might see curation itself as a practice of world-building?

JE: I think that when you talk specifically about this concept of Native apocalypse in relation to science fiction, it goes back to what I said before, where science fiction is placing people into this alien world, or into an apocalypse, where destruction is happening and resources are gone. Native people are already living in that world; we have been living in this world for a long time. That’s what I was really interested in, how Indigenous Futurisms highlight a sense of survival and resistance, the ability to be living in your own apocalypse. So yes, I think any art practice, or any literary, media or creative practice that is speaking to the future is utopia-building. If you’re doing curation with the mindset of inclusion, then yes, I think it’s utopia-building. If you’re doing curation with the mindset of keeping everything in a white cube, in white-run institutions or museums, and you have this collection of “otherness” without really investigating into who has sovereignty over those pieces of artwork, who has sovereignty over those stories, then I think that’s a really scary place to be in.

IH: Your exhibition is at All My Relations Gallery, which is a Native-owned and run gallery, right?

JE: Yes!

IH: Has it been important to you to have this exhibition in that space?

JE: I definitely feel a sense of community working there, and having the exhibition there. I never really had that before, and it’s kind of beautiful and interesting. A lot of people want to think of contemporary Native and Indigenous art as relics of the past and they’re really confused when something isn’t more traditional. They can’t place it. I think having an exhibition with a lot of younger artists whose work is Native because they are Native is really important, and challenging in some ways. It kind of has this effect of disruption, where people don’t exactly know what to think of it. But it’s been really nice to have conversations and highlight why it’s important to have, for example, this video game where you fly as this ancestral bird, the thunderbird, and you use lightning to destroy the black snake, to destroy oil rigs and oil plants. That is actually Indigenous art, because it’s commenting on something that’s currently happening and has happened before, and is using this beautiful element of art to be more palatable to people, so that they can really understand what’s going on. There’s a lot of room for discovery within the realm of contemporary Native art.

IH: I think the inclusion of video games and interactive video art is a really exciting aspect of this exhibition and pushes against that idea that people might be expecting relics when they go to a Native art gallery. I’d love to hear you talk more about the interplay between technology, cyberpunk aesthetics, and Indigeneity.

JE: When I saw Elizabeth’s video games, I think they’re talking about the political and personal in a way that made a lot of sense to me but it wasn’t until I started investigating Santo’s work that I started thinking of Indigenous technology/cyberpunk and how it relates. When I read Santo’s artist statement, they’re really thinking about how the colonial mindset is ingrained within modern technology but traditional Native practices of technology have existed for hundreds or thousands of years. The Paiute People in the Owens Valley created an entire complex irrigation system, only to have it taken away from them. People often have this complicated and untrue view of Indigenous cultures as being less technologically advanced than Western culture. Having a piece like Santo’s, where it’s investigating how cyberpunk can fit into Indigenous history and not the other way around.

IH: What do you hope viewers might take away from this exhibition?

JE: I’d like people to take away that everyone has the right to claim their own future. I think the concept of encouraging a collective consciousness to re-imagine how we see each other is an element that I hope that people take away. I really hope that people can see Native and Indigenous art as being more accessible and expansive.

Ian Hanesworth is a non-binary artist, writer, and farmer from Winona, MN (occupied Dakota land). Their work and research centers on ideas of deep ecology, plant medicine, and environmental stewardship, traversing mediums of textiles, printmaking and agriculture. Their writing has been published on MnArtists, a platform of the Walker Art Center, and in the book Slow Spatial Research: Chronicles of Radical Affection, edited by Carolyn F. Strauss. In their free time, Ian tends a dye garden, preserves farm veggies, and talks to rivers.