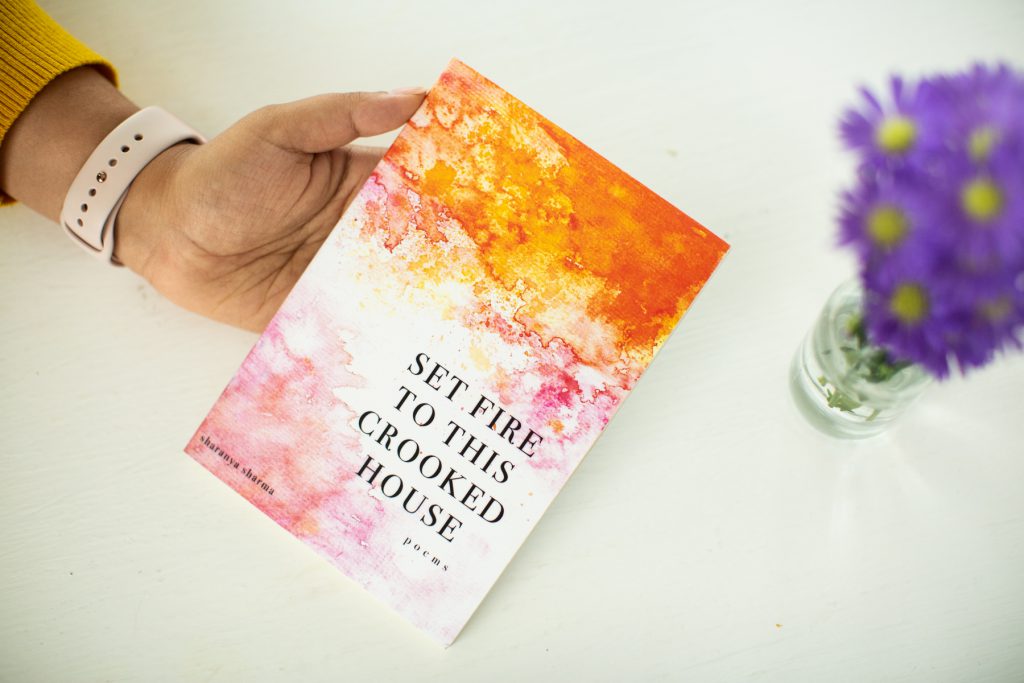

“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. For this installment, I interviewed writer Sharanya Sharma about her MFA thesis project, “Set Fire to This Crooked House,” a poetry collection that she is in the process of developing into a book. We spoke this summer about how her poems re-envision Hindu mythology and critique histories of colonization, especially in relation to museum culture; how acts of retelling can help keep stories alive; and the broader impacts she hopes her work has.

Three poems from “Set Fire to This Crooked House” are published on Sixty here.

Find Sharma on Twitter @sharanyawrites. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Spont-Lemus: I loved the poems you shared at the MFA reading and am so excited to learn more about the collection and your plans for it. Is that program what brought you to Chicago originally?

SS: It is. I was a teacher full-time for six years and didn’t have much time to write. After six years I wanted to do this other thing that was also really important to me! So I packed up and moved here for the program at SAIC.

MSL: How did you come to writing, and to writing poetry specifically?

SS: I don’t know. It’s something I feel like I’ve always been doing? I wrote my first short story when I was around nine. It was a school assignment, probably in the ancient Egypt unit, like, “Write about a day from the perspective of a pharaoh.” Everyone else wrote this very typical, “I woke up! And my attendants dressed me! Then I went to sit on my throne!” And I wrote this murder mystery about how someone was trying to kill this young pharaoh and he didn’t know who. That was the first memorable piece I wrote. I came to poetry later. Around middle school is when I remember really thinking, “This seems like something I want to do.” I was really into rhythm and language — and still am — and poetry captured my passion.

MSL: Did you study literature in undergrad? Or were there other ways your study of writing and literature was supported?

SS: I majored in English and concentrated in creative writing. I think having a really strong foundation in sort of “Western canonical” basics is important to me because I’m able to be like, “Oh, that’s not how my tradition does it,” and compare and contrast the two. In fact, my undergrad thesis was comparing Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie Queene” to the Mahabharata, specifically through queenliness — so the idea of, what makes a queen? I compared a major queen figure of the Mahabharata to how Queen Elizabeth was depicted in “The Faerie Queene.” I think that was the moment I realized, “I can do this! And it’s cool!” [laughs]

MSL: In addition to writing poetry and being engaged with the scholarship of literature, you’ve done a lot of writing about writing. Looking across these various aspects of your work, are there particular questions, concerns, or positions that you think about as being at the core or shared across them?

SS: The fundamental question I’m often asking is, “Where am I, in this?” That was something I was asking when, you know, people gave me Shakespeare. I think part of what led me to that comparison in my undergrad thesis was that I was like, “Well, I’m not in this work, but I might be in this, so let me see where.” What drives a lot of my work — especially in the first section of my MFA thesis — is me asking, “If I’m not here, how do I put myself here?” And feel like this is something I belong to as well.

MSL: Would you say the same is true of work you’ve done about writing? I know you’ve written for BookRiot, done literary programming, etc.

SS: Absolutely! Representation is a huge, important idea to me, especially because I grew up not being really represented — let alone in the “canonical” literature I was being taught in school, but even the young adult literature I was reading as a teen. I wasn’t there. I think now we have started having more conversations around, “What is representation? How do we do it the right way? How do we learn from our mistakes when we don’t?” I think those conversations are really, really important.

MSL: Given that, could you share a bit about how you came to your MFA thesis project, “Set Fire to This Crooked House”?

SS: It’s funny; it actually began in undergrad. I was in an advanced poetry workshop my junior year, and we read this book of persona poems called “Kettle Bottom,” by Diane Gilliam Fisher. The poet was bringing alive a history of a small town in the Appalachian Mountains where there’d been a mining accident, and she wrote from the perspective of different townspeople, to talk about that community, the aftermath of tragedy, and resilience. I realized, “Wait. I could do that.” I loved the idea that, instead of going in as yourself, you could bring alive all these different voices around a certain idea or event. That’s kind of how my project started.

Then, you know, I had to go be a teacher, so the idea sat on the shelf. In graduate school, I thought I wanted to do more fiction, but then was like, “I’ll just take this one poetry workshop….” As soon as I sat down to write a poem for it, my brain was like, “Remember this project you started — like ten years ago?” It took off from there.

MSL: My note from the MFA presentation event — maybe from the person who introduced you — was that your thesis consists of “poems that deal with histories of colonization, especially in relation to museum culture.” Do you feel that’s a good summary? Or, how would you describe “Set Fire to This Crooked House”?

SS: Yeah. It’s a project in two parts. The first part, “Miracles Keep Us Waiting,” is a series of persona poems that re-envision Hindu mythology through marginalized characters, mostly women — again, thinking about how I put myself in this narrative or change it if I don’t agree with it. It’s also about finding one’s voice within mythology.

The second half is called “Prayers Shrieked from the Pistol’s Mouth,” and that was born a year ago from April. As an assignment, we had to go to the Art Institute of Chicago and pick a few objects to write about. Already, I often went to the South Asian gallery to think about mythology I was a part of, or get ideas, or just sit and meditate and let ideas come to me. That was my space to do that. So on that particular day, I was like, “Great! I’m just going to go to my space and find a corner and write!” But it just so happened that, on that day, they had closed off the South Asian gallery, because they were renovating it and moving around the pieces. And I remember having this really viscerally angry reaction to that. Like, “How dare you, I was not consulted, I cannot believe you’re just going to go in and change things and remove things. What is this?!”

So, after that day, I had to piece out my reaction and think, “Why do I feel so angry about this?” It’s a thing museums do. The more I thought about it, the more I realized, “Wow, I really thought about that space and the pieces in it as mine.” Because they were. They did belong to my ancestors. I think I had internalized this idea of, “This doesn’t belong to the museum; this is mine.” But in another way, they don’t really belong to me — and I don’t understand that. When faced with that moment, I dug into, “How did these pieces even get here?” And that led me down the road of, most were stolen, and that’s a thing in multiple museums across the globe. Due to colonization and even post–colonization, religious artifacts — artifacts people were in the process of worshipping — were lifted out and taken away and put in these glass cases. What made me really angry was that even the Art Institute, among many other museums, doesn’t mention that history in the space. In fact, if you go to the South Asian gallery now, there’s a plaque that basically talks about how, “You would normally see these pieces in a temple!” Then it moves on to explain different deities. And it’s like, “Great. So what are they doing here?” They don’t really explain that. The galleries are called the Alsdorf Galleries. Marilynn Alsdorf was a wealthy woman from America who traveled to India and returned with all of these pieces, and then donated them to the museum. But they don’t really get into how she got those pieces or how they originally changed hands. You know, it’s very murky and problematic. The core of my research has been around that, and the practice of how do pieces of another country, another culture, mysteriously end up in Chicago, or in Britain?

There also are personal stories that informed my thinking. My mom took my grandfather to the British Museum once, and he had a traumatic experience in the South Asian gallery. He spent the whole time being like, “They stole all of this! They stole this, and they stole that, too!” Every single piece. “Well, they stole that!” He left feeling very angry. So I asked my family more questions about stories like that and tried to piece that with my research.

MSL: Was that story about your grandfather — which is referenced in a poem — one you knew growing up?

SS: It actually happened a few years ago! And when I had my reaction at the Art Institute, I was like, “Ohhh, I get it.” That’s when I went back to that story.

MSL: In your research, did you come across any places you think are contextualizing those kinds of sacred objects well, or are explicitly telling the truth about their origins, or have even given them back?

SS: There is an organization called the India Pride Project. One aspect of their work is actually finding detailed provenances of different objects around the world and presenting those to the Indian government and saying, “Hey, you need to ask for this back. This was clearly stolen.” I think they’ve gotten maybe three or four pieces back that way, and they’re waiting on one in Toledo, Ohio — there’s a museum there that has an artifact they’ve presented some evidence to and said, “We want that back.”

Unfortunately, with the government, it’s a really slow, painful process of processing everything, and the government kind of getting its act together and formally asking for objects. Because museums won’t just return it without the government asking. I don’t really understand why, but they’re like, “Oh, we can’t just give it back to whatever temple we stole it from. We have to give it to the government, who will then give it to the temple.” It feels like an extra step.

MSL: With both sections of your thesis — briefly, the persona poems then engagement with museum critique — there are distinct but clearly linked and overlapping concerns. Would you say the larger unifying concepts preceded the pieces, or did you find yourself writing pieces then noting shared, emerging themes? What was the process of putting it all together?

SS: The poems mostly formed individually. Often it was just me writing what I was feeling, then cleaning that up to have it be something more than my feelings on a page. There were definitely times where I was like, “Okay, I’m still feeling upset about this museum visit, so I’m going to write a poem that’s different but connected.” But mostly they were very individual. It was actually my advisors who said, “Oh! These five pieces have this feeling, this emotion.” There was a lot of conversation in later stages, where I realized, “Oh, yeah…. That is true.”

MSL: “I didn’t know that motif was there!”

SS: How about that!

MSL: “I just found myself writing it down!”

SS: [laughs] Exactly. “Yeah, I do talk a lot about severed limbs.” That’s something that comes back over and over in my poems, which an advisor pointed out.

In terms of process, later I put all the poems together without really knowing what was going to happen, and then stepped back to see where the themes interconnected or challenged each other. That was really exciting, actually.

MSL: You used the word “visceral” when describing your experience at the museum, and just now you mentioned the severed limbs. In addition to loving the concept of your project, that viscerality really stood out to me in your reading at the MFA event and, later, when I was reading your work on the page. For me, part of that comes from the violence and pain depicted, as well as from an intense bodilyness to the work in general. I wonder if that viscerality is also connected to a certain sense of longing. In many poems in the first section, I felt a longing for recognition or self-fulfillment. As you noted, most if not all are from the point of view of a woman — who it seems was put through a lot or of whom a lot was asked or who was not spoken much of. I also sensed longing in the more object- or institution-angled section, where much of that visceral violence appears in-text. I don’t mean “longing” in a sappy way, but in a resiliency to revenge way.

SS: [laughs] Yeah! I think you’re totally right.

MSL: Like a holding onto something, and a reaching for something. And not letting go of that.

SS: I’m glad that came across, because that’s a really central part of everything I write. The project started because I asked, “Where am I?” And part of it was that women are rarely spoken of in history in general, and particularly in Indian history. From what I’ve gathered, there are many statues to Gandhi and other male figures and very, very few statues to women freedom fighters in India. I stumbled upon that while researching other things. I was reading the book “The Karma of Brown Folk,” by Vijay Prashad, and he mentions these women freedom fighters who still have no statues to them — like Shanti Ghose, Suniti Chaudhury, Bina Das, and Kamala Dasgupta, as well as Pritilata Waddedar. And I was like, “Wait, what?” Without those women, there would have been no independence, or colonization would have gone on for much longer. It was unfathomable to me that we didn’t talk about them, and that this was the first time I was even coming across those names. Because even in my house, and amongst my community here, when we talk about independence, we talk about Gandhi, Nehru, and the major male figures — and that’s pretty much it.

So there was very much a longing to be heard, I think, and to be seen. Because there is such a history of erasing women from the conversation, and particularly South Asian women. I thought, “No, we need to look at this and talk about it!” Not just acknowledge that they existed, but honor the work they did. Even when writing about mythology, I felt the women needed to be seen in a complete way. Because, you know, in mythology, “They were perfect and did everything perfectly, and people did horrible things to them and they were still perfectly fine!”

MSL: “And they were patient!”

SS: Yeah! [laughs]

MSL: It’s amazing how much that maps onto so many different stories.

SS: It really is! “And they were completely fine with how ridiculous the men around them were being.” No. Not only is that not my experience, that’s not how the women who raised me are either. I felt like, “I want myself to be seen and I want the women of this community to be seen in this work, in a way that is true to them.” That was very much at the core of what I was trying to figure out.

MSL: You used the phrase earlier, “representation matters” — and, of course, it isn’t just the presence of a person, it’s how that person is depicted, the complexity and realness they’re allowed….

SS: Exactly!

MSL: That’s as true of historical work as it is of contemporary work.

SS: Right! For me, a big project was being not just “allowed” to have but honoring negative emotions. Because often when I was reading some of those myths, even growing up, I felt like, “This is ridiculous that I’m angry, that we have to have this conversation about how this is not how women actually are or how women should be treated.” Especially when I was younger, there was a lot of, “Well, you don’t know any better. When you’re older, you’ll understand how these stories are important to our religion and blah-blah-blah.” As an adult, I’m like, “No, I’m still mad about this.” And now I’m going to say and do something about it.

MSL: How would you describe your relationship to the source texts or source stories that inspired some of your works, or that you’re critiquing? And I guess, when I say “critiquing,” I mean taking something seriously or not accepting it on face value.

SS: Yeah! Or working to make it better.

MSL: Right! It seems those stories are interwoven into your work in so many different ways.

SS: Those were my bedtime stories growing up. Other people had Cinderella, I had Rama and Sita. And so I think they are so ingrained in my psyche. Often when writing, I would think about a story in a general sense — my feeling within or about the story — and try to find that character’s voice to engage with it as deeply as possible. Then, towards the end of my revision time, I would jot down a few lines about the story in those endnotes, just to give myself a sense of, this is the story I’m responding to. But also, it’ll be helpful for people who don’t know the story. I wrote those endnotes mostly from memory, because most of those stories were, again, so ingrained in my psyche that I could recollect them at the drop of a hat.

That’s something, too, that’s unique, that comes up in my poems about museums. Because when I go to the South Asian gallery and I’m looking at an idol, I’m also recalling a story of whatever it’s depicting. Once I took my friend, who was like, “I really want to see your perspective, can you talk to me about these?” And as I told him, “Well, here’s what’s going on with this idol, and this idol…,” I realized, “Wow, we see so much more than the art.”

MSL: And more than the 150-word–

SS: [laughs] The terribly crafted 150-word blurb about the art. I think there’s maybe like two plaques that delve into the stories a bit? Otherwise it’s very much, “This is the period it’s from, the name of the god or goddess, maybe what they’re doing.” And you’re like, “There’s so much more to this.” It’s something nearly every Hindu kid grows up with, so the vast difference between what I see and what my friend saw was amazing. We’re not just connected to the art, we’re connected to the stories behind the art.

MSL: In the second part of your thesis, which is more overtly focused on museums, was that content also stemming from issues and stories you knew about growing up? Or did you learn about those source materials through research or while seeking inspiration or anchors for works? I’m thinking for instance of the freedom fighter who drank cyanide [Pritilata Waddedar] or the photograph [by Felice Beato, (content warning) Interior of Secundrabagh After the Massacre].

SS: I think it’s all interconnected. When I think of the pieces in the museum, I’m also thinking about the ancestors who lost those pieces and have never gotten them back. When I’m in that museum space, I’m already invoking the ancestors. So in that way they’re definitely interconnected, because I’m thinking of the struggle and how it’s still ongoing, apparently. Even though they fought for independence and got it, justice hasn’t been fully observed.

MSL: You projected images of the South Asian galleries and the Beato photograph during your MFA reading. Once you adapt and publish this collection as a book, do you think you’ll integrate those images with the text or only have them appear through your words?

SS: I definitely see the Beato photograph going with the poem, because I think the image is integral to understanding the reaction to it. But I think the poems around museums are general enough that you don’t need individual pieces in front of you; I’d let them speak on their own.

MSL: As long as we’re speaking about relationships to source texts — I love the reiteration of the prefaces and your poetic responses to them, and how you paired them on the page. And how those prefaces served as a found text that was itself anchored in your source material. Your reframings were so fresh and compelling.

SS: I enjoyed those! That actually started as an assignment, in a class about collaborating with different writers. I was iffy about that class, then one of the assignments was to collaborate with a writer who is dead and I thought, “Well, that could be interesting!” [laughs] I happened to have that copy of the Mahabharata on my desk. All of those prefaces are at the beginning of this particular copy, which contains various editions of an English prose translation, written by C. Rajagopalachari. That was my first time reading the prefaces and I just had so many responses. I was really struck by how much the message changed between, what, 1952 and 1957? At first it’s like, “We’re one nation, and we want to stay away from all the other nations and establish our borders and our culture and everyone else needs to get out.” Then, kind of moving to globalization, “Oh, no, but these stories are for everyone.”

Around the same time, a friend from New Zealand told me about an Indo-Fijian friend of hers. I guess during colonization and after, a lot of Indian and South Asian workers were indentured and went to Fiji. Apparently there, because they were indentured servants, their culture was completely stripped from them. My friend was saying, “My Indo-Fijian friend has no idea about any of these stories. She was never told a single one. She’s trying to find out more about her Indian culture, but it’s proving really difficult, because she’s in Fiji.” And I just remember thinking, “Oh my god.” The idea of not being connected to my culture in that way, of just being cut off from it, was really horrifying. So the series with the prefaces was a combination of me wanting to engage with the writer of the translation, but also thinking, “What about someone like her? Can she still be considered part of the culture? If she is, how do we bring our culture to her? How do we make sure that she can come back, when she’s been so cut off from it?” It’s me trying to bring those two pieces together.

MSL: A number of the poems are about language, and how it is used, even stolen. One I’m recalling now is the poem “effect.” I knew generally the origins of the word “aryan” and some of that context around the figure of the swastika, but I hadn’t thought much about their longer history in the last few years, when they’ve become more publicly present, even in our own city. That poem really got me, and it had so many parallels within the larger work. There’s theft and appropriation around objects, as well as around culture and language. Maybe this is connected to your story about the friend-of-a-friend, too, but there are so many ways your work engages with tongues imposed or taken, conforming or breaking, and the bodily ways a person makes speech. In the poem, it felt not only about language and symbols being appropriated, but in ways that specifically turn back on their origins, where their meanings are changed in a hateful way, and — at least in a U.S. context — even used against the very people whose word that is.

SS: Right! Tongues is another motif that recurs in my work, and I think it’s also because there’s that fear of and anger towards erasure — and being erased, being taken out of the narrative, having someone take your narrative and twist it into something it is completely not. I didn’t think I was going to sit down and write “effect.” I just started writing, and at the end was like, “Oh! This is the poem we wrote! I didn’t realize that was on my mind.” So pushing back against erasure, and against a narrative that has taken part of your narrative, is a big part of what I’m trying to do in these pieces.

MSL: I think that tension between speech and silence came across in so many ways. There were some places where the silence referenced, or the way you played with blank space on the page, seemed to me to be about erasure, and other places where it felt more like resistance. Like, “You don’t get to know.”

SS: Totally. I played with spacing very instinctively in the beginning, and the more I played around the more I was making conscious decisions. It’s still pretty intuitive, but a lot is me deciding, “I want there to be silence here. I want people to stop before they go to the next word or line.” I think it is kind of wielding silence — not necessarily as a weapon, but owning the silence. And saying, “I get to decide when I’m going to be silent. You don’t get to tell me. That’s my prerogative.” That’s definitely part of how I played around with spacing.

MSL: Aside from those you’ve touched on, are there particular artists, writers, storytellers, etc., you found yourself looking to or thinking about while creating this collection?

SS: The Mahabharata is a huge part, and I actually looked at different ways that story was told to me. There was, of course, the oral way, of bedtime stories. I think my dad gave me a prose version — like a novel, almost — when I was eight or nine. Even before that, my parents had purchased these comic books. There’s a huge comic book company called Amar Chitra Katha that produces comic books of the stories of Hindu mythology — and comics about historical figures, the revolution, Indian history and culture. I used to pore over those as a kid. It’s been really cool to return to them, as an adult, and think about how the stories were given to me. It’s been great to kind of triangulate them — the visual representation next to the novel representation and remembering how they were told orally.

In terms of other influences, one of my huge passions is young adult literature. I love writing that is for kids, that is about kids. I would argue that young adult literature is one of the most important genres, because it’s shaping a generation that will hopefully change things. [laughs] That genre is an important influence on how I write, in terms of, “Who is this going to impact, and how? How can I inspire younger people to do whatever they want or need to do?”

MSL: Looking back, how do you feel you’ve grown through making this collection? Or ways you think it will shape what you do next?

SS: It’s definitely brought home to me the importance of poetry in my life. Poetry, or poetical discourse, is actually part of my family’s history. My dad’s dad and his dad were poets, writing in their languages in India. There was a time I was kind of rebelling against that, like, “Well, I don’t need to do what they did.” But I think the past couple of years have brought home to me that, even if I write fiction down the road, poetry will always be part of my life, the core I come back to. That realization has been really freeing, because I don’t have to worry about, can I be poetical or not? It’s just part of who I am.

Even before this, my experience with teaching, at a charter elementary school in northeast D.C., really raised the stakes in terms of how I write. Again, thinking about, “Who am I writing for, and what do I want them to see or feel? What am I writing about, and what do I care about, really?” Because when I look back at poems I wrote when I was 20, it’s like, “They’re nice, they have some nice things going on.” But when I look at poems I’ve written in the past couple of years, there’s a lot more visceral energy. I think that came from teaching young kids, especially young girls of color, and seeing what they’re up against on a day-to-day basis. Working with kids every day and being such a huge influence in their lives gave me a sense of, “Wow, I really need to get this right.” Or really put as much energy as I can into what I’m doing.

MSL: What responses have you gotten to your collection so far?

SS: My classmates have been overwhelmingly supportive, which has been so lovely. I’ve had comments like, “This work is so important,” and “vital to what’s going on right now,” and even “so important to literature as a whole,” [laughs] which I’m like, “Wow…okay.” [both laugh]

MSL: Blurb your classmates.

SS: Yeah! I know. But I’m like, “But you like me, so I’m going to take that with a little grain of salt.” There have been a couple of times during workshops where people are like, “I don’t get it.” And I’m like, “That’s okay. You don’t have to get it.” [laughs] Usually my response to that is, “Either you get it or you don’t and it’s not my job to explain it to you.”

With family, I get some back and forth. For the most part they’re very supportive. I think it’s a little nerve-wracking, especially with the first section, to kind of put out a critique of culture — for any immigrant community. Like, “We’re going to criticize our own people over here for a minute.” Even my mom sometimes will be like, “Oh, do you have to read that poem out loud, in a group? Can’t you just not show that poem to anyone?” I think there’s a little anxiety around that. But particularly with the women in my family, there’s been a lot of support and a lot of, “We see what you’re doing and think it’s really important.” With my dad, who’s very traditional and a very traditional Hindu, I have some interesting conversations around philosophy. It’s been really great to talk to him about that now that I have sort of a standing, and I’ve read the texts over and over and formed my own ideas. He’s also really supportive about the writing, like, “If this is what you believe, then it should be out there.”

MSL: It sounds like this set of stories has always been very alive for you, and I think there’s a way that critical engagement and debate can be a way of keeping work alive! Looking at old texts in new times with new frames can be critique, while also doing work through the act of engaging that keeps conversations and stories alive.

SS: I think that’s totally true. That’s something my dad and I have talked about a lot, actually. Once when I was talking about publication, I was like, “I don’t know what I’m going to do with these endnotes.” Because I’ve gotten some feedback around, “Should the stories be endnotes, or on a page before you read the poem?” I was telling him, “I don’t know if I’m comfortable with that, because they’re not mine, I didn’t write them.” And he’s like, “Yes you did.” I was like, [laughing] “What are you talking about?” And he’s like, “These stories are yours just as much as they are ours. It’s part of our tradition that people write and re-write them, and that’s how they stay alive, by retelling them over and over. Just because you’ve retold them from your perspective doesn’t make them not true.” I thought that was really lovely.

MSL: What’s next for you with the collection?

SS: My poem, “sounds,” is in the Black Warrior Review online edition, and another, “tongues,” is with Silver Needle Press. And I’m researching and thinking about how I publish this project as a whole, because I would love to see it out in the world and have people talking about it. It’s meant to be talked about. It’s meant to be discussed.

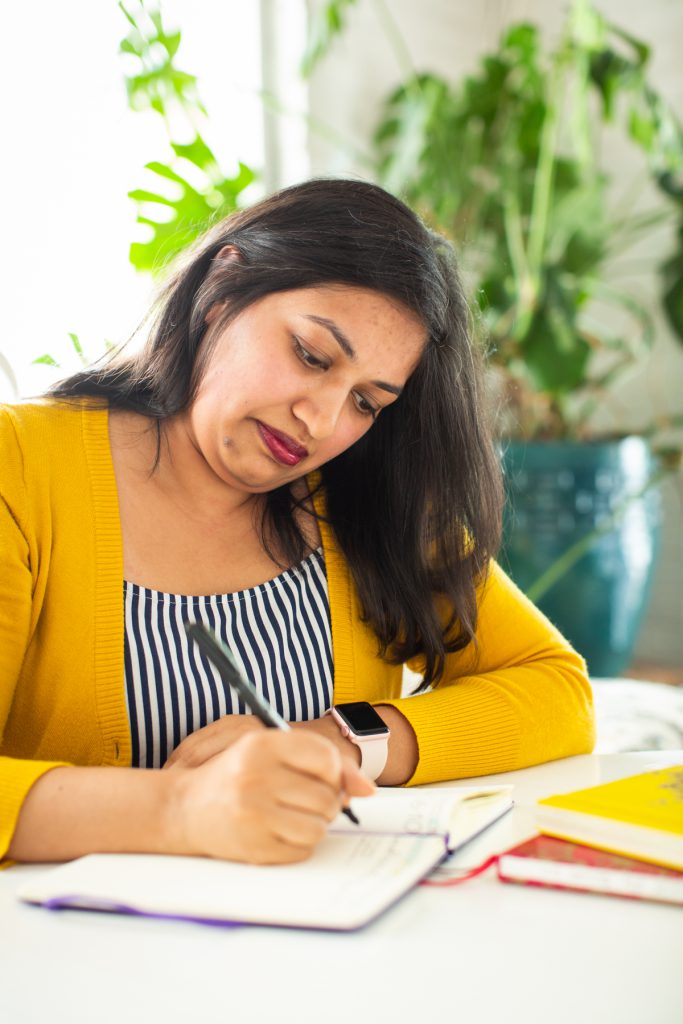

Featured image: Sharanya Sharma. Sharma sits with hands folded on a white table, with copies of “Set Fire to This Crooked House” and multi-colored notebooks in the foreground. Sharma wears a marigold cardigan open over a black and white striped shirt and smiles at the camera. Behind Sharma are several pastel throw pillows and a large plant, and natural light comes through the windows. Photo by Kristie Kahns Photography.

Marya Spont-Lemus (she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Find her on Twitter and Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)