“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. For this installment, I interviewed fiction writer and high school English teacher Sahar Mustafah about her debut novel, “The Beauty of Your Face.” We spoke in January about her process of drafting, crafting, and publishing the book; how her writing and teaching inform each other; and key experiences — and women — that have shaped her as an author.

“The Beauty of Your Face” (W.W. Norton, 2020) is available for pre-order. Check out the book launch event and reading at the American Writers Museum on April 7. Find Mustafah on Twitter @saharmustafah. This interview has been edited for length and clarity, and to limit plot-related spoilers to the contents of the prologue and the book jacket.

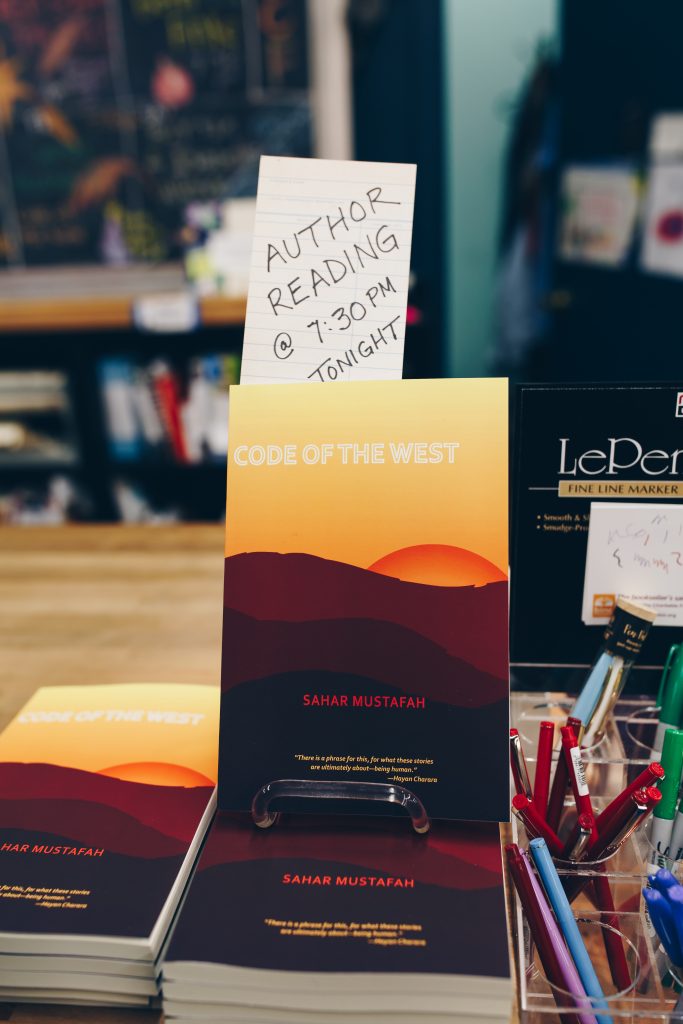

Marya Spont-Lemus: I’ve admired your work since we met through StoryStudio’s “Novel in a Year” program in 2015. I loved your short story collection, Code of the West (Willow Books, 2017), and was completely absorbed by The Beauty of Your Face, your debut novel. I read it over three days and had to exercise significant willpower to not flip ahead.

Sahar Mustafah: [laughs] I really appreciate that.

MSL: Could you tell us a bit about the novel?

SM: The Beauty of Your Face is about the journey of a Palestinian Muslim American, framed by a hate shooting. The novel was originally inspired by the three young people who were killed by their neighbor in North Carolina in 2015: Yusor Abu-Salha; her husband, Deah Barakat; and her sister, Razan Abu-Salha.

As I went through “Novel in a Year” with Rebecca Makkai, I realized, even while getting fairly positive feedback, that my first draft wasn’t going in the direction I felt was right. In some places it felt so contrived. I went into summer 2016 thinking, “Maybe it’s just not going to work,” and left it alone. And I swear, Marya, right before my teaching started up again I had this epiphany: I had too many characters and hadn’t really dug into their stories. I had a reimagination. The shooter pretty much stayed the same; I knew that character would sort of frame the novel but not be the main story. I was more interested in whom he would face, and whether that character would be a victim or survive. And I saw the character Afaf Rahman! I realized, “My goodness, I have to start over.”

The prologue of The Beauty of Your Face starts in the present, with Afaf facing the shooter. I realized the story I need to tell is, “Where did she come from? How did she find herself in this Islamic school, in charge of all these girls? And now having to face this horrible ordeal?” I’ve always been interested in stories about where we come from — in part because of my own background, being the daughter of immigrants and not always “fitting in.” And how would it be different if my parents weren’t immigrants, or from Palestine? If I were white? I’m interested in questioning all of those forces that shape us and carry us into the present.

MSL: After the prologue, we jump back to 1976 and see Afaf’s life, from her point of view, through to that opening moment. Alternating with that is interstitial storytelling from the shooter’s perspective. How did you come up with that structure, and what were you hoping to achieve with it?

SM: I didn’t want to create a stock white-male-shooter. Like with Afaf, I’m interested in where he’s come from, in terms of childhood into adulthood, some of his losses and influences. But I definitely wanted to make him secondary. As I re-drafted, the new structure became moving through Afaf’s life by decade, with the present-day mostly through the shooter. I could still pull audiences into his background through his memories — but not too much, because I didn’t want to detract from Afaf’s story. I still spent plenty of time writing him, so I had a sense of who he was, then edited down.

MSL: Something I hope gets at least as much attention from reviewers as the event of the shooting is Afaf’s story. Not only does it occupy more pages, it involves a huge range of tones and emotional shifts, over years. I was so compelled by her story — essentially, a coming-of-age, formation-of-a-woman story. She’s the book’s heart and center. What was the process of developing Afaf as a character and her journey?

SM: I’m glad you feel that. Some agents and editors wanted me to drop the shooter story altogether. I was heartened, because they felt incredibly drawn to Afaf and her strength. But I was also very set on a particular story I wanted to tell.

I didn’t have any major challenges developing Afaf. I felt this natural progression of what she might experience, beginning as a 10-year-old, with each decade offering something formative. The book is completely fictitious, but does reflect the kinds of experiences I’ve observed in circles of friends and family. It felt like a realistic story of a young Arab girl in Chicago — something I relate to and see myself in, that my sisters will be able to see themselves in. Closer to when Afaf begins her religious transformation, some of those moments are inspired by communities of women I’d been exposed to growing up. In the ‘90s, there seemed to be this renaissance of Islam, at least in the south suburbs where I was living, with women really turning to Islam and wearing the hijab. Those moments in the book are plucked from really positive celebrations of women making that formal dedication. Not that they didn’t identify as Muslims to begin with, but to be visibly Muslim is, I think, quite an intentional choice and a journey.

To me, Afaf’s story feels sort of like opening up an album and seeing different snapshots that formulated her sense of identity or lack thereof. By the end, I think she seems fully realized. And, in her case, it’s because of not rebelling — whereas rebelling often feels like a typical narrative, like the child of immigrants saying, “I hate my background! My parents are not cool! Why can’t I be like my white counterparts?” Afaf certainly struggles with not belonging, because white people have also kept her out of their realm. She felt like an outsider and it’s exacerbated by a lack of cultural identity, religious identity — she didn’t belong anywhere, even with her Arab community. Afaf being accepted by the circle of women is just, I think, the best story of Islam. It sort of lights her way to loving and forgiving herself, healing, and managing grief.

MSL: While there are ways in which the book is about hate, to me it more essentially seems to be about love. One way we see that is through Afaf’s relationships with her immediate family and family in a broader sense — those women, her friend’s family, her students.

SM: The relationship between Afaf and her brother was so enjoyable to write. That is my favorite. And the one she has with her father. As flawed as Baba was, Afaf never doubted his love. The love of other women, to me, is such an extraordinary kind — sisterhood, not by biological means but through friendship. Whatever the elements are that make up a community of women; in this case it is definitely religious and also ethnic. Those relationships were important for me to draw out and spend time on, because I didn’t want the shooter frame to overwhelm Afaf’s greater story, which I felt was universal, ultimately. I’m thinking readers will go away with, “This was about friendship, about broken families….” And it’s not going to be, “This was about a Muslim girl and a hate crime.” I very much appreciate you saying that and I’m glad that comes across. Maybe in some ways that love allows us respite from the violence that frames the book and is threaded throughout. She definitely experiences moments of bigotry before encountering the shooter, but she seems better equipped because of all these positive relationships.

MSL: The novel’s present-day storyline depicts that epic act of anti-Muslim violence, while Afaf’s stories over the decades include various slurs and abuses, almost like part of the texture of her daily life. How do you see those as connected to each other? Why was it important to you to show those moments building alongside the story of the shooting?

SM: I guess it’s the absolute, most horrendous, culmination of all those things. It’s our worst nightmare. People keep calling it “the unthinkable.” But I’m like, “It’s actually not unthinkable,” at least not to people who experience those smaller moments every single day. I don’t think, in the end, it is ever shocking when something like this happens. It doesn’t mean it’s any less rattling or horrifying. But, it’s not so unbelievable.

I wanted to make sure I spent time on how Afaf’s life shifts almost instantly when she puts on the hijab. I didn’t want to blow over that. Because audiences know, we all know, about Islamophobia. But do we? Do we know what it’s like for a visibly Muslim woman on a daily basis? I don’t! This is me imagining, doing research, talking to Muslim women who wear hijab. I hope I did that justice. Because here I am, someone who typically is not identified or immediately recognized as Arab or Muslim by others. People go through a whole list, and I’m like, “We can stop this game of trying to guess where I’m from. I’m from Chicago.” [laughs] Having to step into that — with research, and collecting stories — was moving and humbling, to say the least.

I heard an amazing StoryCorps that Yusor Abu-Salha had done with her teacher, Mussarut Jabeen, before Yusor was killed. Yusor talked about how much she loved America, how this was her country, and how happy she was to have these opportunities to be educated and so on. She was just so optimistic. And I guess I thought, quite cynically, that it felt almost like the narrative that immigrants or Muslims or Arabs are expected to recite, this burden of, you know, “We should be grateful to be here.” But I also thought, “I wonder if I’m kind of steering Afaf into another single narrative. How hopeful that Yusor felt this other way!” Whatever experience Yusor had with bigotry or discrimination, she didn’t feel compelled to address. I like to think, ultimately, what this book will do is challenge what people think or expect. Because it’s not, “Oh, Afaf comes from this really happy, devoted, Muslim family.” That’s not the case at all. A series of things brought her to that. And that’s what I was interested in — things that, unless you ask someone, “How did you begin? Where did you come from?” you won’t know.

MSL: Most of Afaf’s present-day scenes are in past tense, and her past decades are in present tense. I found that shift to be very emotionally impactful.

SM: Oh, good! I think it felt natural. Practically, it was important to differentiate the shooter from Afaf and her story. Her decades being in present tense is, for me, to make those experiences very immediate and alive for readers, because those stories basically created who she was. For me as a reader, that’s what tends to happen with present-tense — I’m seeing and feeling everything with the character. Even any degree of discomfort, I’d want that to be visceral, as visceral as I can depict it.

MSL: To me it also quite literally made the past feel present. Which made sense, because it seems the past is very present for Afaf, and for her parents — like she is negotiating her relationship with the past and its impact on her.

SM: Absolutely! Those stories — our past and experiences — still live in us. Sometimes they’re going to come to the forefront, some can be very triggering. And I didn’t want Afaf to be a Muslim American principal and people not know more than that, or for her to be pigeon-holed or a flat character. I very much wanted her to be a human being, with all of these things having happened to her, and to have the reader experience those through her.

MSL: At what point was it clear to you that the protagonist would be an educator? Or that a central location would be a school?

SM: Once I saw Afaf as a single character, in my second draft, I knew she would be an educator of some kind, and I definitely saw the Islamic school as the setting. In the first draft the shooting was in a public location. But I thought, “No, he needs to enter the school” — a place where, obviously, children are supposed to be educated and protected and safe.

MSL: How familiar were you already with the communities where the novel takes place — Chicago’s South Side in the ‘70s and ‘80s and the south suburbs more recently — or what kinds of research or revisiting did you do?

SM: I was born on the South Side, where I was raised before living in Palestine for some years. I wanted to realistically depict my neighborhood during that period. The suburbs, not just Orland Park where I live presently, became my adult life.

The novel’s suburb is fictitious, as is the school, though I partially modeled that on Islamic private schools I’m familiar with. And I struggled with, “Do I name the suburb?” I didn’t want to have to worry about people saying, “But this wouldn’t happen here, and this doesn’t accurately depict us,” or “Well, I’m from that suburb, and we love that Islamic school!” I didn’t want that to distract an audience. Other aspects, like most street names, are real. Authors have told me people get very sensitive about these things. And, quite frankly, I think this particular book is going to be in front of a larger audience than my short story collection and, inevitably, people are going to be critical. So I thought, “What do I want them to be focused on?”

Rita Dove said something in an interview that has stayed with me — this is a paraphrase — about how being a “hyphenated” writer carries double burdens, like of representation while still having to be a good writer. And other authors have talked to me about fighting any suggestion that you’re published “because” you’re from a certain background and fulfilling a particular “need” in the publishing industry — the white publishing industry, really. That has been troubling to me. I’ve carried that and had to negotiate that. Because I’m hearing those white critics; I’ve had to sort of silence them to get the work done. But I don’t pretend that I won’t be under the microscope with this book and what I’ve accomplished here. So even something as minor as not naming a real town was very deliberate. I don’t know, maybe every writer feels that kind of hypersensitivity and fear.

MSL: What brought you to writing, and particularly to writing fiction? Was it always as much a part of your life as it is now?

SM: I was always a big reader, and in the high reading groups. The scene with Afaf and her class is inspired by my experience — except unfortunately she didn’t have my experience, which was teachers elevating me. I’m grateful my teachers were able to see that ability. My mom and dad could functionally read English, but they didn’t read to us at home. So where this love came from — innate! I don’t know. [laughs]

I started writing when I was 8 or 9, and I begged my parents to buy me this Corona electric typewriter from Sears. I saved as much as I could and they put in the rest. They really nurtured that enthusiasm. I was writing funny stories about animals and things, not anything that directly reflected who I was — I think because those stories just weren’t available. For me, white characters were the default, and white writing was the default of what was “good” writing — that was the way I saw it. So, in that sense, I would write for fun, and it came easily. But I never ever had the notion that I would be a writer. In fact, I had so much pressure to be a doctor — you know, from my immigrant parents — as soon as they saw my straight As. [laughs]

I was writing personal essays in high school — and actually winning school contests — and I had this really wonderful journalism teacher. For one assignment, I wrote about how my sister cut my and my younger sister’s hair on the same day my mom hired a professional photographer. My mom had already dressed my sister and me the same, in boys’ clothes. My mom didn’t really differentiate — whatever she liked is what she bought, which I guess is cool, looking back. And the photographer was like, “Okay, boys, get closer.” It was a humorous story. That teacher wanted me to send it to Reader’s Digest! And I didn’t think it was good enough! I just couldn’t imagine being published. A different teacher accused me of plagiarism, not believing I could write something. Luckily she went to a previous teacher who said, “That’s the way Sahar writes!” I’ve told my own students about that, when we talk about moments adults have disillusioned us or let us down.

When I started writing “seriously,” I was well into teaching. I had come across a book of essays by Naomi Shihab Nye and thought,“Wait. There’s this self-identifying Palestinian American–?” It blew me away. That’s not to say I wasn’t aware of Arab writers in translation. But here in America, she gave me my first inkling that there’s space for Arab American writers. And I discovered that Arab American writing didn’t have to be “exotic,” although what I’d been exposed to felt exoticized and maybe I was even pandering to that. I’d been strictly writing stories set overseas, worried that any story I’d tell here — that may have derived from my own experiences, my immediate communities — wouldn’t be valued. That took some years to get over. For example, I had written a collection set overseas — which I know was also coming from my time there; I love Palestine. But, look how naïve I was, I sent the collection to this major publishing contest. And I was a semi-finalist! But the judge compared me to Naguib Mahfouz. I was like, “The Nobel Prize winner in Egyptian literature?” Of course, at the time, I was over the moon. Not until years later did I realize that might have been her only reference! I’ll never know that; this is me projecting, maybe my sensitivity about where I fit in the publishing industry. And the comparison was to a male writer, who didn’t write in English.

I happened to meet Naomi Shihab Nye at an English teacher convention. And, Marya, I was like a friggin groupie. I gripped my friend Nina’s arm like, “That’s Naomi Shihab Nye!” I ran up to her, and she was a lovely human being. The next year, I brought a big pile of stories and, [laughs] though Naomi graciously declined to take them, she recommended places to send to. One was Mizna Magazine, which later published a story. She also connected me to Radius of Arab American Writers (RAWI). I had felt very much alone and — of course! — there’s a whole community of Arab American writers! Who, before the internet really exploded, I just didn’t know. Many knew each other, through the college network, but I was a high school teacher. Naomi really opened the door for me to find that community.

MSL: Were those experiences before you went back to school for your MFA?

SM: Yes. I didn’t get my MFA until relatively recently. After I started sending out stories and getting, you know, a lot of rejections but also pretty good feedback, I realized I needed a more immediate community and someone to read me regularly. I felt like I hadn’t quite found my voice or the possibility of myself as a writer. I had gone back for an MA in English, as part of my professional development for secondary ed, then decided I needed to do something meaningful for my creative writing if I was going to really pursue it.

For my MFA, I was going to Columbia College three nights a week, not getting home until 11pm. It wasn’t a physically healthy time but I loved it. I started exploring stories that I’d maybe been suppressing telling because I didn’t think anyone would be interested. I had wonderful instructors, including Patricia Ann McNair and Megan Stielstra. My publishing credits started to build, just being in the program. Beyond those staple journals, I realized there’s the online and smaller fish — like “I can be read.” That opened my eyes to possibilities in terms of different audiences, smaller audiences, and audiences of color, for women. That’s probably why I was so happy to start Bird’s Thumb, with Nina Dellaria — an online literary journal for emerging writers that we co-edited from 2014 to 2019. I wish we could have kept it up, but my writing now is much more involved, and I still teach full-time, so I had to make that decision.

MSL: I know you’ve written short stories extensively. What was the transition into writing a novel like?

SM: I like to experiment with my big ideas as long short stories first. That allows me to finish a particular arc and not be intimidated by the scope of a novel. I think what made this novel manageable was the way I framed Afaf’s story by decade. Those very much felt like short stories! They had open endings, so you still wanted to know, “Where’s this going to push her?” I wasn’t intimidated about pages as much as, “Will I have developed hefty smaller plotlines to carry me through?” Have I “raised the stakes” in every chapter? Because that wasn’t a conscious concern in my short stories. I think I was doing that naturally.

During my MFA, I wrote what I considered a failed young adult novel – basically hearing that the publishing industry wants someone like me to produce a certain story and me falling into that trap. An instructor had said to me, “Why are you wasting your time here writing a short story collection? You should write a YA novel.” That almost derailed me. And my wonderful mentor there, Patricia Ann McNair, was so mad at that professor, like, “How dare you tell Sahar this is more marketable.” I really have always respected that integrity. I’ve got to stay true! They may not sell a whole lot, but short stories remain my heart and soul.

MSL: What’s the relationship for you between writing literature and teaching it and the writing of it — particularly to high school students?

SM: Before I started really devoting myself to writing, I was not on a conscious level appreciating the author’s craft. For me — and I think a lot of English teachers can speak to this — it was about plot, theme, symbolism…all these necessary yet traditional things. But not, “How does the author build towards that theme? How does she use language to make us feel a particular mood, or to make us laugh?”

Now I focus more on “the author’s craft,” as I call it. That can be very challenging for students, who have always been quizzed on, “What was the theme? What happened? Who did it?” I have drastically moved beyond that. I’ll compare a piece of text to my own writing experiences. I’ll say, “I’ve tried to do this technique…” — I’m constantly bridging. I want students to know that the author has put a lot of work into writing and made very deliberate choices. As much as I’ve said, “this was fun to write, this went smoothly,” it was still work. I want reading to be enjoyable, and to stress that it’s enjoyable probably because of all these things the writer is doing. I don’t know that students are generally encouraged to look at writing that way, unless they’re in AP English classes, but to me it feels like we’re giving authors their due respect. I appreciate everything I read, even things I don’t like. I want students to be able to say, “I did or didn’t like this because.”

And the teacher as writer, as artist — it’s such a privilege. My students are so wonderful. I want them to see they can have more than one life. Seriously. I tell them, “I have been teaching all of my adult life — and look at this! I’m also writing very seriously. I want you to know you can do as many things as you want.” That, to me, is how I define success. Am I following and fulfilling these creative impulses? I am! It might not have come when I was young, like some writers, but I feel like everything has really put me on or supported this path. I’ve been living, and teaching, and that has shaped what I’m putting out there now.

MSL: Am I remembering that you’ve encouraged students to share and submit their work, too?

SM: It’s so powerful for students to discover, “Oh…other people want to read my stuff? People are interested?” That begins immediately with their classmates, when we have open mic or small-group critiques. Some get a wonderful sense of a larger audience — maybe national, like Teen Ink, or school-wide, through the lit club magazine I sponsor. But, no matter what, I hope I convey that publishing doesn’t have to be the end-all. I want them to appreciate that writing is good for the soul. It’s a very mindful act, which is why I’m so interested in writing as healing — a new direction I’d like to take.

MSL: As you look back on your development as a writer, are there particular people who have been key along your journey? They might be people you know, or whose work has been an anchor or guide.

SM: This is such a wonderful question because, of course, the way you phrased it is people first — and then “or maybe books….” I love that.

MSL: And I recognize that books are written by people. [laughs]

SM: But you didn’t say “authors,” and I think that’s remarkable. Because the very first person I thought of is my good friend, Nina Dellaria. What can I say? Nina was my first fan. I showed her my folder of stories right before I approached Naomi at that conference, and I’ll never forget the look on Nina’s face, like “How have you not shared these?” To this day, she’s read everything first. She’s been an extraordinary rock. I’ve had some horrible experiences and she’s always been there to raise me up. I wouldn’t be here without her. Because it takes that one person — if not for her, I might have tucked my stories away. Nina is unequivocally the force that brings me here to share this with you.

I’ve had major female writers as instructors or mentors, who have impacted me maybe even more than books. Megan Stielstra has revealed to me that you don’t need to be defined by a particular genre, you just need to tell your stories, whatever they look like, and you need to take risks. When I thanked her for one of so many opportunities, Megan said something like, “You need to keep the door open after you, so that others can also come through” — which another woman writer had told her. That has stayed with me. How can we continue to elevate each other? And especially those who need elevation, who are “on the fringe,” because of gender, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, whatever the case might be. Patricia Ann McNair, my Columbia College mentor, continues to support my work. There’s Chris Rice, editor of Hypertext Magazine out of Chicago. I think of all these women who say instantly, “Sahar, how can we help you?” I think of organizations, like StoryStudio and Guild Literary Complex, and independent bookstores like Women & Children First, who don’t just feature me but will ask me to be in conversation with somebody. My sister found them before I did. She’s like, “There’s this great bookstore…and they have books by Arab women.”

The list of wonderful literary voices is boundless. I love Laila Lalami, a Moroccan American writer. I love Jhumpa Lahiri. She gave me a sense that I can write short stories representative of my community and people would actually buy the book. Susan Muaddi Darraj, a Palestinian American writer, is someone who lifts up other Arab writers, particularly Arab American female writers. She’s done so much to promote the work of our community.

I find that I am endlessly surprised by good books and good writing. I don’t feel I need to read everything by a single writer, but it’s important to keep opening myself up to different writers. I’ve never personally understood this idea of writers not reading while they’re writing. How could I not read?

Featured image: Sahar Mustafah sits outdoors, smiling and looking off-camera. She wears a black winter coat, light grey scarf, and large hoop earrings. A bush with tan leaves fills most of the space behind her, with greenery and parts of a building behind that. Photo by Mark Blanchard.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)