“Beyond the Page” digs into the process and practice of writers and artists who work at the intersection of literary arts and other fields. For this installment, I interviewed Regina Martinez, Threewalls’ Artist and Artistic Engagement Manager, about the In-Session program — a critical interdisciplinary salon that incorporates reading, conversation, and performance together, now entering its third season. I spoke with Martinez in late July about the ideas and values behind In-Session, the theme she chose for its coming season, sensitivities of working between artists and institutions, and Martinez’s own path to and through this work.

Check out In-Session’s third season, themed “The Art of Memory.” Find Threewalls @threewalls on Twitter and @three-walls on Instagram. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marya Spont-Lemus: Thank you for taking the time to speak with me about In-Session! I’m so glad I went to Udita Upadhyaya’s In-Session event in March, because I think this program has such a great premise and I’m excited to hear how other artists engage with it. Especially for readers who may not be familiar with the program, can you share a bit about what In-Session is and how it came to be?

Regina Martinez: In-Session is really one of the visionary programs of Dr. Jeffreen Hayes, who came on board as the Executive Director of Threewalls in 2015. It is a pillar of the programming that she envisioned to really, I think, manifest her values for the organization — which is a shift from where the organization originally started. It was always hyper-supportive of experimentation and artists’ work and artists’ process, and I think Jeffreen takes that to a new, really potent and significant level that much more accurately mirrors the artists that are living and working in Chicago. And I think that that process has been about a defining, redefining, and dismantling of a lot of the things that I think artists have faced in the city, particularly artists of color and particularly Black artists.

So In-Session is one of our pillar programs at Threewalls. It is an interdisciplinary discussion activated by other layers — sound, movement, poetry. The most distinct way I’ve heard it described, by Amina Ross who was also a participant, is, “Experimental conversation led by an artist.” The values of Threewalls that I think it truly manifests are collaboration, vulnerability, and the true experience of racial equity. You can read a lot about the definition of the program on our website, and I never have one way that I talk about it, but In-Session is always based on a theme, and the theme and its reading list are usually cultivated by the staff internally. The first theme was “Migration,” the second was “Citizen(ship),” and we’re heading into our third season now, which is “The Art of Memory.” There’s a thread between all of those too, I think. They’re all timely, they’re all sort of nostalgic. In-Session is really an opportunity for an artist to use space to talk about their experience with the theme, and to guide the conversation in a collaborative way — usually with 2-5 collaborators guiding. The artist is also guided by a text that they choose from that theme’s reading list, to have a very participatory discussion with the folks who show up. Jeffreen calls it sort of a remix of the panel discussion. Every In-Session is so extremely different, and there are so many moving parts.

In my role managing In-Session, I have the pleasure of getting to support the artists in their vulnerability. And that’s a word that I think has become a trending word. But just because we say that we want for vulnerability to be part of the experience, it really takes a very particular context of care for that to actually become. I think that’s what we’re learning here, through this program. After the In-Session that Amina led, I remember that Jared Brown, one of the artists Amina worked with, wrote us an email saying, basically, “Nowhere else would we have been allowed to take it that far,” just in terms of what they really wanted to say. They participated in the theme that was about migration and used a short film by Marlon Riggs called “Tongues Untied” as the text. The In-Session events are meant to be standalone performances, but I think it’s beautiful how artists have also viewed In-Session as an extension of things they’re already working on. Amina Ross at the time was wrapping up curation of the first ECLIPSING Festival. Even though it wasn’t really a direct tie, I think they envisioned their In-Session to be an extension of that process.

I’ve learned, Marya, from my position here, honestly so much more about myself and what’s been affirmed in me as an advocate for artists. I didn’t know how deeply I cared, [laughs] until this role. Which is a strange thing to say, because I’ve been working in the arts — working organizing, directing, managing — for almost ten years now. But with the project that I worked on in St. Louis, which we’ll get to, the main focus was young people who were spending time in a space — and me organizing the teaching artist ecology was a huge part of it, which I learned a lot from. But the young people and their families who were showing up and who made that space what it was is what the priority was. In this role, it’s been different. Threewalls’ audience really makes sense to me as artists. And In-Session is a beautiful space where artists are coming to explore an idea and their artist peers are really the ones that are in the room helping them do that.

It’s been really rewarding to be a part of manifesting this program from the very beginning. That was the beautiful rhythm of the timing of my start here. Jeffreen had really set the stage. The nuts and bolts of the programs existed, but the programs really hadn’t happened yet, they were just on the cusp of happening. And so I’m deeply privileged that she has acknowledged me as someone who can come in and be a part of rooting them. Even not until I’m saying this now, do I even feel the heaviness of that, or the magnitude of that, or the gravity of that. And I really care about Jeffreen as a leader and as a person. So there’s an additional layer of just wanting her to feel confident and comfortable about the trajectory of the program, even though, because of the degree of vulnerability, it can kind of start to creep [laughs] faster than you would maybe imagine.

One aspect of that is that, in the beginning, it wasn’t quite as clear to me that it was useful for the artist to have someone else moderating. I think oftentimes when artists are presenting their ideas, they want to wear all the hats — performer, curator, organizer, moderator. I’m personally okay with that, but I’ve learned from Jeffreen that it’s actually really useful to have another dimension to it, to sort of enrich it further. As we get further along, I think the goal is for that person to potentially not even be an artist — for it to become really, really, really transdisciplinary. Because that makes sense! Because the subject matter is mental health, it’s chemistry, it’s physics, it’s all the things that would naturally begin to invite other ways of thinking. And that’s exciting to me.

MSL: You’ve brought up vulnerability a couple of times. I’m wondering if you’re willing to share some of what you mean when you say that vulnerability is a value of the program, or how working with artists in manifesting the events has made you think more about vulnerability, or how vulnerability is a word that more organizations are using now — just sharing your thoughts on that?

RM: Yeah! Yeah. [pause] What I’ve learned is that, sometimes when we think we’re being vulnerable, we’re actually not? Because there are so many invisible expectations in place — whether you put those on yourself, or what you perceive the institution you’re working with to expect, or the goal of the program. So you can’t really just, like, be in the middle of an idea and share it publicly. You know? I think the vibe that we create in this space and internally on our staff is different. I feel like it’s really an unspoken goal to break down all of those walls that seem to say that we need something to look or feel or be experienced in a certain way. I think that artists, creative people in general — anybody — are still always going to put those expectations onto themselves. I think it’s impossible not to; we’re fish in water. But in this particular space, in this particular program, with this particular staff, it’s the first place where I’ve experienced the greatest depth of an artist’s willingness to tip over into that readiness to say, “This is literally the first time I’m….” Like, “I may identify as a visual artist but I’m really moved by this theme and by this text and I just have an idea that I want to share, collaboratively, and it can be half-baked and it’s okay.” You know, often there are so many frameworks in our life where there is pressure to feel really buttoned-up in a way. I feel like this is a place to kind of breathe differently.

But it’s also supported. It’s not just a free-for-all — like sometimes what I think I would allow for it to be. [laughs] One of the things I’ve really learned from Jeffreen is the power of the editing process that happens in the relationship between myself — my role — and the artists who are doing In-Session. Because the ideas really can get like wildfire, but you only have two hours and there are still these things you have to adhere to. So the editing process, I think, becomes a part of the vulnerability, because artists inside of a process aren’t always ready for critical feedback about any one component of a thing. It’s really about establishing that relationship in that conversation in a relatively quick amount of time, so that that conversation can flow to the most powerful concentration of their idea. I think that those things have to do with vulnerability, too. You have to be in a spiritually vulnerable place, I think, to receive feedback. And you have to be in a spiritually vulnerable place to know when it’s time to give feedback and when it’s not. So, for me, vulnerability isn’t just a value, it’s a way of being and communicating that, I think, a lot of times we don’t make time to do in programming and in bigger institutions? And some days, I think Threewalls is a small institution but it’s really a huge institution because of its legacy. It’s existed since 2003 and then the very important work that Jeffreen’s doing to get it to now, for me, makes it huge and hugely significant.

MSL: Yeah. Something I’m hearing in that is vulnerability also in relation to an emotional or social attunedness — like understanding vulnerability in the context of an artist’s relationship with a structure or institution, and acknowledging how that might feel really different for different artists and with different institutions. There’s an aspect of that attunedness even in being on the same page as each other around the expectations for a program or the ways in which you all open up the space and open up yourselves to help facilitate a program while also helping, as you say, with editing. And I feel like it’s almost like pre-editing. I think the call for proposals for this season clearly articulated up-front, “This is generally what an event looks like, this is how much we’ll pay you….” I can’t tell you how many opportunities I see where I’m like, “Okay, but are you paying the artists or not? How much?” So there’s this aspect of vulnerability that can also be about transparency — which is another word that gets thrown around a lot. [laughs] But it means a lot to me to not be put in that position as an artist and for other artists to not be put in that position of having to ask or negotiate all of those things around, “What does ‘support’ look like for our event? You say you’ll ‘support’ it, but what does that mean?” I don’t know if that’s always been a part of the In-Session process or if the application has shifted over time, but I noted it.

RM: It was really transparent in the first call, too, in terms of pay. But it’s gotten more detailed in terms of, you know, example structure of night. Which of course still ends up shifting because the night ends up moving like a cloud. [Marya laughs] Anything with performance, you know. And because the audience is truly so involved. Audience participation is such a huge value of the program that a direction an audience member might take could totally throw the quote-unquote “timeline.” So there’s openness to all of that. Talking about vulnerability, I’m still questioning if I really know what it means.

MSL: And I think it can mean a lot of things.

RM: Yeah, it can. I appreciate you including the aspect of how the call for proposals looks. Lauren [Williams] and I were talking about this the other day — like reasons why it’s difficult for people to ask for help. In the context of working with artists, I’ve learned a lot about what many artists are not willing to ask for just because they don’t know that they can, or should! And it could be a huge thing, it could be just a tiny thing. I think, as creative people, we’ve all gotten kind of used to going with the flow — but the scales are really, really imbalanced. So you get home from a meeting or conversation or performance and something doesn’t feel right but you don’t know what. So I like what you said about that sort of “pre-editing,” almost like setting the stage.

But there’s no measure for, “Okay, success.” [Marya laughs] Like, “The artist feels really supported and everybody felt vulnerable and we did it.” Because I think about every one that’s happened, still. I think about the nuances and the ingredients and the energy of every single In-Session, and each one makes you feel so different. And it’s not always that you feel good! That’s part of it too. It’s that willingness to be really uncomfortable almost all the time and going on that journey with the artists, who are also willing to feel uncomfortable. It seems like a simple thing — and I think “discomfort” and “uncomfortability” are also words that get thrown around — but this is really the first place where I’ve experienced the things that I hear all of us talking about. In a programmatic sense. In the work that I did in St. Louis, I felt it all the time because it was just really intimate work.

MSL: What originally brought you to Threewalls? Or put you on the path towards Threewalls?

RM: The path started, really, with knowing Jeffreen from when she was the Executive Director of Rebuild Foundation. The project that I managed in St. Louis was called the Pink House, and it was catalyzed by Theaster Gates and supported by Rebuild for the first 4-5 years of its existence, beginning in about 2010. Jeffreen was the ED of Rebuild in 2013-2014. So we met and just had always stayed in touch after she left Rebuild.

And just a bit about Pink House: It was a really intimate neighborhood art space. It was a salmon-colored house, situated halfway up a residential block in a north side St. Louis neighborhood called Pagedale, which is in the Normandy school district. It was lovingly called the Pink House because of that salmon color, and that house has been in that neighborhood for 50-plus years. A community development organization called Beyond Housing owned that house and had reached out to Theaster back in 2010, getting on that boat of, you know, community arts engagement, social practice, all of those conversations that were floating around at the time. He was becoming so known for this, doing all of this work on the South Side of Chicago with Dorchester Projects and establishing Rebuild Foundation. I was based in St. Louis at the time — getting my masters at Wash U in social and economic development — and I had an internship at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, which he was also doing a project with, so I met him and Dayna Kriz. And he had had this opportunity, this invitation from Beyond Housing, to do something with this little house. I got a phone call one day in 2011, just, “Hey, would you be interested?” Dayna was already working on another project in St. Louis in the same vein, but a whole different partnership in a whole different part of the city.

And, Marya, I often say I can just drop the mic after Pink House, because it was just the most fulfilling work. It was the most fulfilling work. And it was fulfilling because the way that the partnership was set up — with Rebuild Foundation being based here and the community organization that owned the house, yes, being in St. Louis but being this massive institution that really wasn’t paying attention to the day-to-day of what we were doing — we could really just be and do. It wasn’t about this external gaze all the time or sharing that, you know, children and particularly children of color, Black children, were “safe in art class” somewhere and the photo op. Sometimes, more often than not, we had a presence on Rebuild Foundation’s blog and on Beyond Housing’s website, but ultimately we were just there at Pink House every day after school, in creative exchanges with artists who lived across the street, or across the city. Pink House was a place on the way home and whoever showed up made it what it was. And every day it was just like making a mark that you weren’t even aiming for. Because if you spent time there, it just had such a natural rhythm. You know? And we just kind of managed to dodge all of the hyper-formalities that tend to make these places a little less interesting to spend time in. It felt like you could truly be yourself.

That project lasted for about six years, then it closed on a decision that was really by Beyond Housing. That’s a whole other story that’s honestly a whole different article — one was written in the St. Louis (Missouri) American publication about its closing [link]. That work was just so important to me and made up so much of my St. Louis experience that when that project ended, I really couldn’t see myself in St. Louis anymore.

I was still in touch with Jeffreen and I think that the timing just kind of ended up working out. Because not seven or eight months later, there was this position at Threewalls. So that’s really how I got here.

MSL: Wow.

RM: I appreciate you asking the trajectory question about what brought me here. I also organize an event in St. Louis called “the clothesline,” which has taught me a lot of what I know about collaboration. I do it with two other women, and it’s a one-night-only amalgam of light and sound, or visuals and sound. I think a lot of that — Jeffreen even following the momentum of that — is also how she’s gotten to know me as a facilitator, a connector, a collaborator. But clothesline and Pink House, those were what was keeping me in St. Louis, and I was there for 8-9 years before coming back here. I would have never met Jeffreen without that.

MSL: Were you in Chicago before that?

RM: Mmm hmm. I went to University of Illinois for my undergrad and then moved here and lived here for about five years. I moved back to St. Louis for my masters, did that work at Pink House, and now I’m back here. So it’s been the Midwestern thoroughfare, Mississippi River, for most of my life.

MSL: I can see how there may be resonances between the work you are doing here and the work you were doing in St. Louis — in terms of values, arts-connected, based in relationships, facilitating relationships between other people — but also I imagine that your role here is really different in other ways.

RM: It’s really different. But, like how you just described, I think I’m an intuitive connector. Have you ever been introduced or email-connected to someone and it just didn’t really make any sense that you were being introduced to them? [Marya laughs] Maybe this is a bad example. But I think there is something to be said about seeing all the dots and knowing when it’s time to connect them — whether that has to do with longer-term relationships or shorter-term collaborations. I’ve found a lot of purpose in that, in being sort of this connective tissue in that way. And, yes, that’s certainly a thread between Pink House and this work. A bit less in this work, just in the sense that I’m really here to support the collaborations that are being organized by the artists themselves.

And relationships — that’s another thing that we give lip service to. And collaboration. Because I think collaboration is a critical skill, and just because you’re working together doesn’t mean that you’re collaborating. You know, I think our culture really rewards this illusion of hyper-individualism and all those things, and I think sincere collaboration happens less often than we think.

MSL: What do you think marks it?

RM: Oh, that’s such a great question. [laughs] [pause] Well, the answer is kind of cheesy, really, because it’s things like, you don’t have to give up your ego to be a really good collaborator. It’s almost just like how your ego listens. [Marya laughs] Like, it’s one thing for you to be listening, but for your ego — your goals or aspirations that are transpiring inside of you, in kind of a different layer of yourself — for your ego to be listening also is another thing. If that makes sense.

MSL: Yeah. I know collaboration and partnership aren’t the same thing, but that makes me think about how, to me, an ideal partnership — or maybe a “sincere” partnership, though I hadn’t thought of it in those terms — is something that is genuinely helping both or all partners. It’s supportive in making their lives easier rather than harder in doing the things they’re trying to do.

RM: Definitely.

MSL: Because, to me, partnership is about finding the points of interdependence or mutual support, finding the ways in which people feel good about giving or feel the space of their own need, and that those things are coming together in a way that makes sense for the people involved. Especially in arts administration or education, different positions or roles I’ve had in the past, it’s been so interesting to see people be like, “Oh, we’re doing this partnership….” And it’s like, “But why? This is actually making things more complicated.” I think making things more complicated can be really great if it’s because you’re being critical about something — like you’re wrestling with the complications or engaging with the complexity of something. But if the partnership is actually just making everybody’s life harder and isn’t better serving the missions, whether organizational or personal, it’s like, “So, why are you doing that?” Maybe cynically, “Just for some optics?” Rather than really asking, “Are we working together towards something that is beneficial and shared?”

RM: Exactly. And I had never thought about the ego listening until I’m talking to you. [Marya laughs] But it’s making sense, even listening to you talk, because I think the thing that does complicate it is when collaboration doesn’t allow for all of those things that you mentioned, just in terms of the mutuality of it. There is a lot of ego in creative work! And I think we should still honor that. But there’s a way for those things to be honored if listening happens also at that level, at the level of the ego.

It’s like you know it’s happening when you see it. And there have been teeny examples of it not happening. Like if an artist asked another artist to serve as the moderator, and that person was like, “Hmm. I don’t want to be involved as the moderator but I want to be involved doing what I do.” So then that didn’t work out. That’s an example of listening to each other to figure out how it’s of mutual benefit. And it might not have been of mutual benefit for that person to be in that role, and that’s fine!

MSL: To shift gears a little, or kind of circling back, I’d love to hear a bit about how the themes and texts come about for In-Session? Like where those come from, and how much those come from the process itself or from the ideas that are arising through participants’ work? From the outside, it seems like there might be some responsiveness to or just building over time on the previous themes and lists.

RM: I think that the building over time certainly exists. “Migration” was the first theme, which Jeffreen selected back in 2017 and I helped develop. We had a wonderful administrative intern at the time named Omar Dyette, who was hugely significant in organizing that first season with me. I think migration, as a theme, is truly a visceral response to the things that have been happening politically in our country and everywhere in the world, particularly things that we’re bombarded with. As a team, really with Omar’s lead, we were responding to that theme with the different texts, then of course we all added other ideas. There’s not a super formal way that happened.

“Citizen(ship),” the second theme, was a little more formal because there was a conversation between us and the MCA around the performance “What Remains,” which was happening with Will Rawls and Claudia Rankine and was based on her book “Citizen: An American Lyric.” That ended up adding a different layer to the In-Session program because it helped us as a staff to focus all of the other readings, but also gave us opportunities to convene the In-Session artists with Will Rawls and the MCA staff and, you know, just be invited as kind of a cohort to the performance and again for a debrief with Will. It added another kind of glue to the whole series that also added another kind of glue between the participating artists, which I think we learned a lot from. That more external partnership didn’t happen the first season, and it also isn’t happening with this current season.

Then for this season, the theme I chose was “The Art of Memory” — Jeffreen encouraged me to choose and she developed the reading list with me — and it felt like another breath in the same chord of migration and citizenship. And I’m a deeply nostalgic person, to a fault, so the idea of memory and how memory moves and what influences it is just something that I’m always thinking about. And there are so many artists who are addressing that in their work.

So there’s nothing super formal about how themes and reading lists happen yet. As a staff, we’re not choosing the proposals. We get the proposals and then we have a committee that we select as a staff that reads and selects them. There has been conversation around what would it look like for the committee that we’re working with to have more of a hand in selecting the texts. We are kind of still figuring out all of those parts. But so far it’s been a pretty intimate process in terms of our own invitation to ourselves to have creative input on how this moves. As I’m talking to you, at least with this last one, it feels kind of arbitrary? [laughs] But it’s not, at the same time.

MSL: Yeah, and all three of the themes so far seem, as you say, in some ways to be very relevant to our present moment — but also were never not relevant.

RM: Exactly.

MSL: So there’s sort of both a specificity and a breadth.

RM: Yeah. I’m glad you said that because they all do feel pretty broad to me. I don’t know what would be an example of one that wouldn’t feel broad? That might take us down a strange rabbit hole. [both laugh] Like, “Pine Trees.” I don’t know. But sometimes the breadth, I think, can feel overwhelming, not necessarily even to the artists who are applying but to the committee. We got feedback like, “Is this too many texts?” We’ve had that discussion internally as a staff and we also don’t want it to feel like this really academic thing, like where everyone’s reading the same book. But, at the same time, I think the sort of glue of Claudia Rankine’s “Citizen” also assisted in everyone having, potentially, a commonality of shared experience — either knowing or having read this work, or knowing who Claudia is. We’re still figuring out how necessary shared experience is for this. Because with In-Session, say the guiding work is Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust,” there’s no guarantee that even 50% of the audience has seen that. So that was one of my questions with the committee this season, selecting these proposals. Is it more beneficial, in the long run, to work towards that? To ensure, somehow — and you really can’t — but to put things in place to ensure that everyone in the room at an event has experienced the text already.

MSL: Or even just going out of the way a few weeks before an event to send a reminder to the Threewalls listserv like, “If you’re coming, we strongly encourage…! And here’s where you can find the text!”

RM: It might be something as simple as that, where you do just remind people. And I will be using that. [Marya laughs] Because I’ve learned that sometimes the guiding text gets kind of lost. You know, I think people become aware of the theme or they just know they’re coming to support this particular artist — and the rest of it just ends up being an experience, and the details of it kind of don’t matter. All of that is a part of it, too. But for those people who do want to experience it, you know, somewhat closer to how the artist is experiencing it or performing it, I think something as simple as encouraging people is helpful. Highlighting what the guiding text is more feverishly.

MSL: I love how many forms of media were on the “reading list” — films, poems, music, books…and the section that’s just visual artists’ names and then “tell us what work you’re responding to by the artist.” Maybe that’s another way the specificity and breadth thing comes through — like, the theme or invitation is broad, the guiding work or inspiration is specific, and something happens between them.

RM: That’s a beautiful way to frame it. Yes.

MSL: I also love who’s represented across the guiding works, and the fact that these reading lists you’ve created are now out in the world. I wasn’t thinking about it when I asked about the lists, though I do like to ask about influences, and I do think a lot about influences in my own life. Especially, like, who sets “the canon,” and what does it mean to be a “well-read literary fiction reader” or whatever when you aren’t interested in that canon? You know, these expectations within a given institutional structure or among certain sets of people that to be “an informed such-and-such” or to be engaging with “the important works” means x, and what perspectives and even styles and values that typically does and does not include. I’ve personally and professionally had so many moments where I’m pushing back on someone about that like, “No, I have my own influences.” Like, “Cool, I’m glad you think it’s important for me to have read that, but I actually think it’s important for me to have read all these other things. And I am too ‘critically engaged’ because I’m critically engaging with those.” I feel that dissonance or gap and I’m a white person. So my sense even just from looking at this season’s reading list, or hearing how central “Citizen” was to last season’s, is that making and circulating the reading lists also just seems like such a great way to center and promote another, largely different set of texts that are mostly by women, people of color, queer people, from a lot of different places, with distinct sets of concerns.… That may seem like a really obvious thing to say — like it’s maybe an obvious observation from the lists — but I think it’s worth speaking to that value of them.

I think the other thing I’m trying to come back around to is how we as artists and we as people are carrying all kinds of influences with us all of the time but we’re not always speaking what those are. They may be in the DNA of any of our work, but we’re not necessarily taking the moment to say, “Actually, do you know that what was really important to me in developing this set of ideas was work by this person?” I’m sure that the artists who are responding directly to one text for In-Session are also bringing DNA from lots of other texts in with them too. But this framework is just one way of setting or highlighting an influence among many, and doing it in a way that can also act as a recommendation or reference-point for others.

RM: Yeah, and I’m glad you pointed it out. It’s funny because I had the largest hand in creating this current list, and I didn’t even think about it. You know what I’m saying? It’s just who I know, who I think about when I think about this theme. It really didn’t have an identity-based driver — but it always does, just based on who I am and where I choose to work. There’s also a poem, “May This Be a House of Joy” by Lucille Clifton, that either Jeffreen or Lauren will read before every In-Session, setting a tone — not since the very beginning, but for some time now.

But yeah, it is rewarding to share this reading list. Even one of our committee members hadn’t read or seen a lot of the texts, but she was so excited about it and was like, “I’m going to be looking into all of these.” The list is just another way of coming together, another way of being re-inspired. Because we’re such a small staff, and because I end up becoming so engaged in the scheduling and what the artists need that even for me — and not having an intern currently — some of those parts end up falling off in importance. But I’m glad it’s being paid attention to, because it’s a huge part of how the program operates and functions.

This season will be a shorter season, and there are two artists who have selected the same text! It was like, “Ooh, is that okay?” Well, of course it is. [both laugh] You know, even those little funny questions pop up. I’m learning as we go and being as open as possible.

Segueing into influences, Bhanu Kapil is a huge, huge, huge influence on me personally, and she created the video for the performance you came to. She’s a poet and a writer and, formerly, a professor at Naropa University in Colorado. She’s had a huge influence on my work since I was at Pink House. And [laughs] talk about vulnerability. Because of her involvement in Maya [Mackrandilal] and Udita’s performance, Bhanu sent me her W-9. [Marya laughs] I was just nerding out. I played it cool for the first few exchanges, and then two months later, after their performance, I wrote to her — which is not something I do. And Marya, within two hours, she wrote me back one of the warmest email responses I’ll ever receive. Ever.

So this program makes a lot of waves, I think, in the ways that we question ourselves creatively, that we question our own influences. Like even me, coming up with the theme “The Art of Memory.” I had so much internal resistance. “Is this theme going to make sense to anybody? Are these texts going to make sense to anybody? Is this call for proposals this season going to be exciting to anybody?” You know, you question yourself. And that’s all a part of it, just doing it.

And I’m learning things that I don’t even know I’m learning, that will come up in a totally different context. Like there was a moment this last weekend where I viscerally experienced organizers transferring way too much responsibility onto an artist — in a moment, at a program that I was participating in as a member of the public. And I interjected like, “Can this go another way?” Thankfully, it did. It seems like a simple thing, but we have it down to a science in our culture how to exploit creative people. Any medium. We have it down to a science. And I didn’t know how moved I would be to figure out how to release some of that in my small role here at Threewalls, or in my relationships with creatives because of Threewalls and beyond. I didn’t know how rare it seems to be either.

MSL: Yeah. I think sometimes we realize that we’re growing or we actually do grow most in those moments where we’re pushed or called on? You know, maybe you just hadn’t had the opportunity before to be prompted on that, like, “Oh, I actually do totally know this, it’s totally core to the way I operate, but I haven’t had that drawn out of me because I haven’t had to consciously stand up for that.”

RM: Exactly. [pause] So good to know!

MSL: Are there any past In-Sessions you haven’t already mentioned that really stand out to you, maybe because of a personal resonance they had, or the audience conversation, or an unexpected engagement with a text?

RM: Oh, gosh. I remember someone saying — and I’ve felt this before myself — that just being in the circle of one of the In-Sessions was an experience they didn’t even know that they needed. There have certainly been specific examples for me. A.J. McClenon closed out last season. Her In-Session was with Angel Bat Dawid, who’s a musician, and the moderator was Israel Pate. Angel plays many instruments but there was this really incredible moment where she was playing the saxophone in front of footage of former president Bill Clinton playing the saxophone. And it was just [pause] unforgettable. That was in response to Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow.” There was just something about that moment. But trying to think about things that have come up in conversation — there’s just been so many.

MSL: Or even things artists have shared with you after going through the experience.

RM: Little things will happen even inside of the internal communications between performers that they hadn’t discussed. [laughs] Just those very important nuances that, as a staff member, I become privy to. This process brings out a lot of sensitivities from everyone who’s involved, including the audience. I don’t think there’s a way to really prepare for that, as a performer or not. I’m always really inspired by the artists that are willing to go there! We talk a lot about “process,” you know, and “prioritizing process.” What I’ve learned is that it’s not always that attractive for an artist to share all of that! And so I think there’s a lot of sensitivity around acknowledging process. I think we have to ask what about process. What about process are we so enamored with? Especially in arts administration. Because I feel like it’s becoming so focused on “process over outcome” and all of that, where process is more important. But there’s something to be said about the intersection of vulnerability and mystery. For me, when I think about the artists that I’m inspired by, Bhanu being one of them, that intersection exists. And just because we’re talking about vulnerability doesn’t mean that we’re asking creative people to let go of, you know, the mysterious aspects of their practice that make their process what it is.

MSL: Mmm hmm. And vulnerability doesn’t mean an all-access-pass or an all-access-pass for everyone.

RM: Yeah! Sometimes I think that’s what we mistake it for, when we throw these words around in a way. Somewhere, that’s what someone’s expecting to come and get.

MSL: As if you go to an open studio and you’re allowed to completely go through everyone’s everything, as opposed to just what they have put out for you to see.

RM: That’s the other thing, being part of the support system that kind of houses all of it. I’ve learned, being here, that some people shirk away a bit from this notion of intimacy. Like, “Ehh, that’s not really for me,” or, “If I read the word ‘intimacy’ in the description of a program, I’m not really going to go to that.” So, you know, it’s just being sensitive to all of these factors and experiences. And then the privilege of working in a space that is run, on the staff, by 100% people of color. Which I’ve also never experienced before. And as a white-passing person myself, depending on the context I’m in, I’ve learned a lot about that too. And what it really means to be able to be here, with Jeffreen, right now, as she is defining leadership for herself in a way that is totally different from other things that I’ve experienced. Part of what I think enables us as a staff to figure out how to kind of move inside of these sensitivities is because of how Jeffreen cares for herself and us as a staff. “Self-care” is another trendy thing. She’s somebody who deeply embodies it for herself and for us as her staff. She truly does. I don’t think I’ve ever experienced anything like it — because it’s just not our culture. It’s not our culture to care for yourself in the context of work. Not really. Not systemically. That is something that is very, very real for her. And it’s necessary. I think that the artists we work with can feel that on us, that she’s prioritizing that for all of us. Which changes the expectations, I think, in general.

MSL: Yeah. This conversation makes me think about the idea of boundary-setting. And I think a lot of intimacy can be about boundary-setting. It’s saying this is and is not what is okay in this scenario. Whether that’s boundaries for relationships between staff and artists or an artist and an institution, between a person and their job, or between a person and their artist practice and the rest of their life.

RM: I’m glad you brought that up. Because boundaries is a word that I really struggle with. Jeffreen cares for me a lot in that way because I think she witnesses me struggle with those. I’m someone who sort of feels like true life is lived in between our responsibilities, like between work and whatever my responsibilities are for the day. So if a sincere relationship is possible, then, for me, I don’t always know how boundaries fit into that. Almost like I don’t really have them but I know when you’ve crossed one, or I know when one’s been crossed? And I’m not saying that that’s not a healthy way to have boundaries — because that might just be who I am — but I think this role really requires that I do have them. I think that’s something I’ll continue to learn way after this job.

MSL: Looking back at the In-Session program thus far, what are you most proud of? Or looking forward, what are you most excited about?

RM: I guess I’m proud that I’ve become comfortable being a part of developing it, almost like film in a dark room — because there are so many unknowns. And In-Session already existed before I got here, I’ve just had a major role in manifesting it. I’m proud that I haven’t been hard on myself for any of it. Like I’m really just letting it show me what it is, letting the artists show me what it is, letting Jeffreen support me in showing me what it is. I’m allowing for that. It feels like such an opportunity to aspire to meeting an expectation that is unknown. There’s not an expectation in the sky or that’s written on the wall somewhere. I remember an email that Jeffreen sent to Omar and me at the end of the first season that was just really warm, congratulating us and thanking us for bringing her vision to life. As a creative person, I’ve never been in this position where I’m part of the responsibility of bringing someone else’s vision to life, and it’s maybe more daunting than if I were bringing my own visions to life. [laughs] So I’m proud that I haven’t been hard on myself for any of what could be imagined as a shortcoming or a snag or whatever. I owe a lot of that to her. Because she allows for the solitude and the freedom but also she’s there to help form it. I’m proud of myself that I can be at peace with exactly where things are with it.

I got a text from an artist a couple of days ago, which was literally, “You have my back and a lot of artists feel the same way.” It was such a vague yet intimate text to get. [Marya laughs] I don’t know exactly what they were referring to but it meant a lot to me. I feel like having someone’s back, even in your personal life, can be a very elusive experience — because, again, of how the ego works and just primally how self-preservation is a thing. So even the notion of having someone’s back, there’s a lot of grey area there. There’s a lot at stake in having someone’s back. It becomes very familial in that way. Like the potential to have to have someone’s back when actually the integrity is off. Or, you know, when it is a clear case of potentially someone — anyone — trying to take advantage, maybe too far of a thing or across too far of a boundary, and still having the capacity or wherewithal to understand what “having someone’s back” means, in this context. Where there do have to be boundaries, where the creative process is sensitive, where vulnerability is maybe happening. It’s a very intuitive process. And there’s not any real getting it “right.” It’s just, “How did you feel after?” I’m very thankful that, predominantly, I think artists have felt good. If they don’t feel really, really good about it, maybe they really saw themselves or learned a lot from putting themselves in this position to do this.

And there have been other nice moments. For the first reading list, for “Migration,” Omar chose a poem by a locally-based poet, José Olivarez — who ended up coming to the In-Session and having a role in it because of how that process ended up moving once he learned his work was a part of it! [Marya laughs] That was very cool. That was, in fact, the second In-Session we ever did — Jose Luis Benavides with Nancy Sánchez, Amanda Cervantes, and Daniel Haddad. I think if Omar were sitting here, that would have been their proudest moment. They were proud of that synergy.

MSL: Was it unusual that Bhanu Kapil both wrote one of the guiding texts and then was part of the resulting piece?

RM: That’s never happened before — other than the time it happened accidentally, that I just mentioned. [pause] That’s what was incredible. Duh, that’s going to happen eventually, that someone who’s applying for this knows this person personally, can email this person and ask them to collaborate. And then I’m getting her W-9. [Marya laughs] It’s beautiful that already in our first three seasons that degree of synergy is coalescing. Because that’s, again, the dots connecting themselves, when it’s time to connect them. It feels really, really powerful when that happens.

So this program has a lot of legs and power inside of it. It comes together with the artist-led, experimental conversation and performance aspect, the moderator, the text, the theme. It’s a lot of ingredients that makes this stir. I’m thankful for this conversation because there are still so many ingredients to me, and being so up-close to it working with the artists I don’t have a like [snaps] “In-Session is this.” Yet. And I hate elevator pitches anyway. But conversations like this help me concentrate In-Session down into its most powerful aspects.

MSL: Not the grant speak, but the stuff that actually feels really important.

RM: I will never be the grant speaker. [laughs] I learned that about myself a long time ago. That’s another thing about Jeffreen — she really knows who she has working with her. Even when it becomes challenging how different we all are, she really has a way of honoring what we bring in a way that values the whole person. I don’t think I’ll again– [laughs] I’m always talking like life is over soon: “I’ll never experience this again.”

MSL: [laughs] You did say you were very nostalgic. I don’t know if that’s what you meant, being nostalgic about something happening in the present.

RM: I’m very nostalgic. Being nostalgic can be very dangerous because it’s denial of my future, really. But I’ve worked for a lot of different kinds of people and this is the most wide-open it’s felt in terms of the holistic care of myself. I’m never worried. If I’m ever worried about something, it’s that there’s just more to be done and somehow I’m too scattered to do it. But it’s not the other pressures that I think we tend to feel, in terms of performance. Everything is a conversation — that’s what In-Session is, too. And my role here is kind of like a cloud. It’s got to somehow figure out how to be direct and flexible at the same time, constantly.

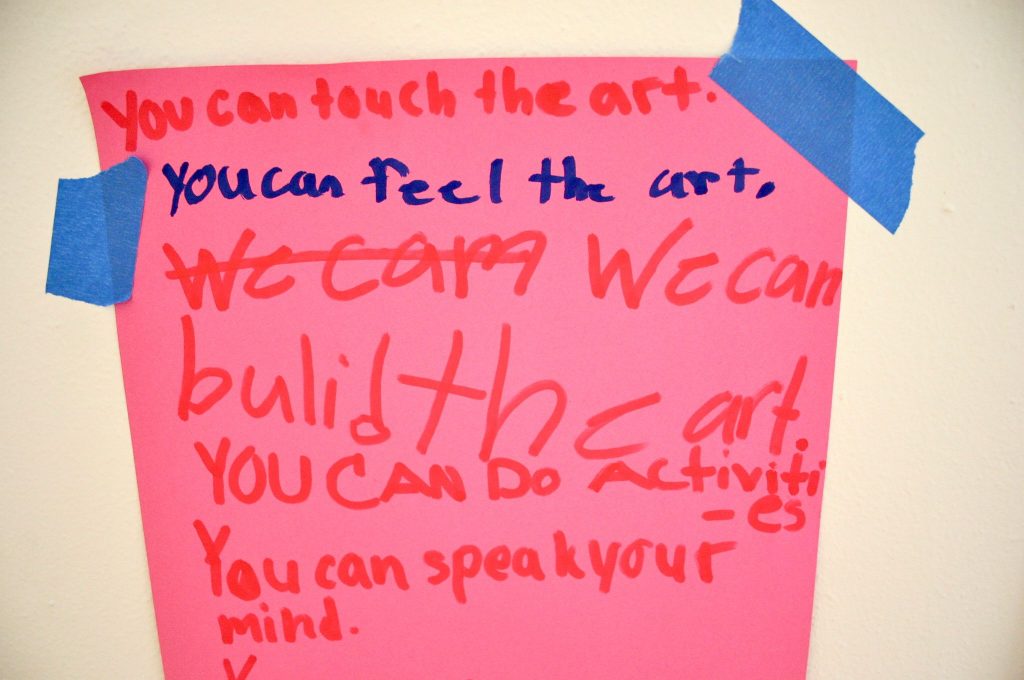

Featured image: Regina Martinez (center) at Threewalls in March 2019, participating in an In-Session by Maya Mackrandilal, with collaborators Udita Upadhyaya and Enid Muñoz and original performance for video by Bhanu Kapil, in response to the guiding work “Schizophrene” by Bhanu Kapil. In this wide shot, Martinez and more than a dozen audience members stand in the middle of the wood floor at Threewalls, as Mackrandilal and Muñoz stretch fluorescent pink ribbon around and between them all. The room is low-lit, with some additional fragments of light reflecting onto the audience members from a video projection off-camera. Martinez wears black and white and a long black sweater. Most audience members wear sweaters, scarves, boots, and/or hats. Photo by Milo Bosh. Courtesy of Threewalls.

Marya Spont-Lemus(she/her/hers/Ms.) is a fiction writer, interdisciplinary artist, and educator focused on teen creative, leadership, and professional development. She lives and works on the Southwest Side of Chicago. Find her on Twitter and Tumblr.

![[placeholder image]](https://sixtyinchesfromcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Quenna-Lené-Barrett_Headshot-300x99.png)