“Go to Zhou B Art Center and check it out for me. Let me know what you think,” Mateo says.

“Alright, will do!”

Visiting Chicago with my younger brother Mateo means moving through the city like it’s our stage: darting into incense shops, snagging banana pudding ice cream when the bean pie runs out, browsing used bookstores, and catching golden-hour light on the train tracks. Mateo—half transit nerd, half philosopher—shifts easily between quoting infrastructure facts, clowning around, and dropping the perfect insight for the moment. I trail behind with my tote bag, equal parts deep thinking and sibling goofiness, happy to let him guide me. Together, our rhythm is earnest, playful, and reflective—a choreography that sets the scene for how I experienced this exhibition.

I got to the Halsted Orange Line first and perched on a ledge, earbuds in, halfway through an episode of Hunting Wives on Netflix. When Mateo finally appeared—collared shirt, slacks, leather messenger bag slung across his shoulder—he looked like the grown-up version of the kid I used to tease, mustache and soul patch still clinging to his baby face. I paused the show, tugged out my earbuds, and stood up, excited to tell him about my Bridgeport adventure he’d sent me on after my flight was delayed. We did a quick recap outside the station, then hopped on the train to Midway and fell into our usual rhythmic gabbing.

“How was it?” Teo asks expectantly. He loves telling stories in order, while I zigzag like the alleys he’s always dragging me through.

I look up and am momentarily transported to a massive white-wall gallery, alone, soaked from a torrential downpour. I begin to tell the story.

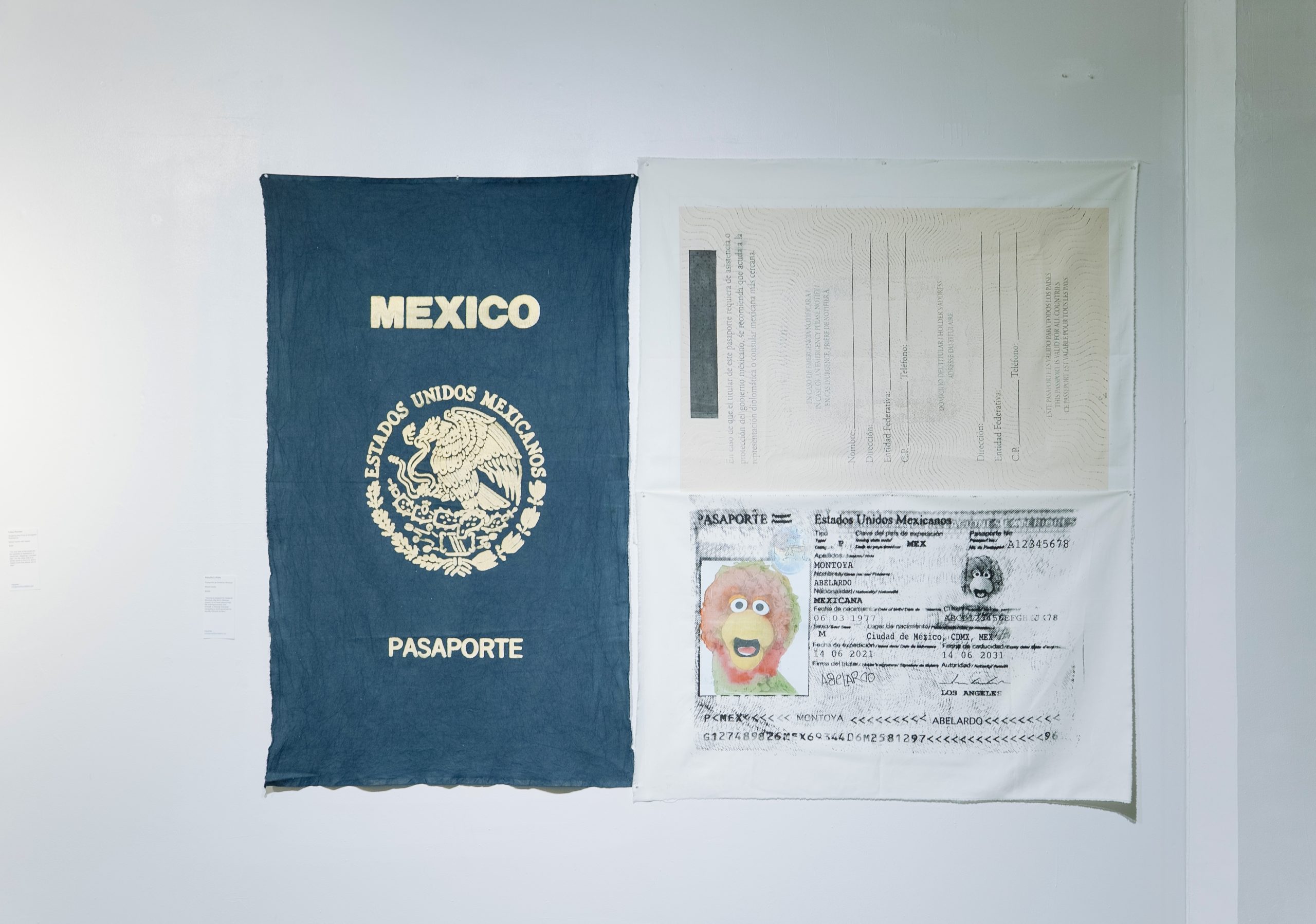

“There are so many immigration shows, and this won’t be the last,” I say. “But what stood out to me was how abstract it was—almost faceless—except for Big Bird.”

“Big Bird?” he grins.

“An artist silkscreened a passport of Big Bird onto a huge white sheet. Anyway, I digress. In this show, the material did most of the speaking.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Hmm, it may be easier if I put it this way: there was an artwork called Turn to Your Neighbor by Mason Brown, I say, smirking. We look at each other with deep knowing. I hand him my phone to look at the picture I took from the show. “What do you think?” I asked. Before he could answer, I jumped in, too excited about the work.

“It’s so Black church-coded, right? Ew, I sound so Gen Z, but you get me. It is a quilt pinned to the wall. It’s double-sided, but if I were a smartass, it would be called recto-verso. It was intriguing how an object could be pinned to the wall, and you could see both sides. Maybe hanging from the wall is a better assessment. On one side, it has adinkra symbols stitched in, and on the other side, it has these beaded appliques as brilliant as the brooches or patterns on dresses that church ladies wear. Like out of a page of the Ashro magazines, Mom used to get.” It’s just like me, asking his opinion, but then chiming in with my thoughts again.

Mateo zooms in on the photo. “That green pattern on the adinkra side—it’s tucked behind the fold.”

“Exactly. There’s this controlled reveal—showing both sides but deciding how much of each you see. A duality. Speaking of, there’s this Carina Yepez piece you’d like—Entre Espacios.” I hand him the phone.

He studies the photo: a large-scale weaving made of two photo transfers—one of a Cicero alley, the other of Mexican farmland—cut into strips and woven together.

“We are seeing two things at once,” he says, “But one blurs the other. It’s like teleportation. Wouldn’t that be a cool power, bro?” His nerdiness starts to flare in the best way.

“Yes,” I admit. I agree more than he knows, more than I articulate. My time in Chicago always has an expiration date. I am keenly aware of my own migration within the US (Syracuse to Pittsburgh to Boston to Philly); sometimes I feel like I’m always teleporting.

“For my internship,” he adds, “I studied the Chicago Green Alley program—permeable pavement to absorb stormwater. Did you know Chicago has more alleyways than any other US city?”

“Noted,” I smile. “Anyways…another work that I wanted to get your perspective on is Delaina Doshi’s work, which she refers to as a ‘tesserae quilt.’”

“Yeah, the ceramic shards are kinda meta,” Mateo says. “Like—fragments scavenged from different thrift spots, stitched back together. Migration as reconstruction.”

“You know, I have to bring up the first work I was gravitated to in the exhibition. Sorry, I know you hate when I jump around, but I’ll get back on track, I promise. But, I made a beeline for Rebecca Leal’s two-headed horse-monster with a snake-like tail, bat wings, and a sun-halo.”

Mateo questions, “What drew you to it?”

“The indigo, magenta, and mauve colors and the texture of it look so soft, yet it is a monster. I’ve always had a fascination with mythical creatures and monsters. It even reared its head in my Horror of Karen zine that I made because when I was in Lithuania, I was struck by a quote that asked if cultural diseases could be contagious and calling them chimeras– but of course I pronounced it ch-im-er-uhs one time and it haunts me.” I wait a beat before asking, “Do you think monsters are real?”

Mateo side-eyes me at first as if to say, What are you on right now. Then his gaze shifts into a smile. “You remember how, as kids, people have night lights because they are afraid of the dark, and how there are monsters under the bed. Try telling a kid that isn’t real. It’s the belief that is the real monster that you have to grapple with.”

“Very psychoanalytical, Teo! I like it, Picasso,” I giggle, referencing a viral phrase at some point. “On the label, it talked about how it is inspired by ‘pantasmic existence about the identity as being neither and both Mexican American.”

“Hmmm,” Mateo engages with the thought for a second, but it must drift away because there’s a pause.

I nod. “Now—let’s talk about the theme. What do you think We Built This Making Through Migration means?”

Mateo leans back like he’s about to deliver a TED Talk. “Well, obviously, it’s about people moving and making stuff.”

I roll my eyes. “Wow. Groundbreaking. Truly Pulitzer-worthy insight.”

He smirks. “Okay, okay—seriously? It’s like… migration isn’t just about moving your body from one place to another. It’s moving your skills, your traditions, your style. You’re building something new with all that you carry.

I chime in, “Like how Mom and I make collard greens with cannellini beans. I’ve cooked them with ham hocks or we do it with chicken bones or turkey legs, whatever’s available.”

“Yes! Food is art. And migration makes the recipe better. Same with quilts, ceramics, alleys—whatever. People bring their bricks, and together they build a city, a culture, a vibe.”

“Let’em cook.”

“Stop it. You can’t say that. It’s not you,” Mateo chides.

“What’chu mean? That’s what our generation says, don’t they?”

Teo shrugs me off and continues, “In this case, migration’s not just survival. Its contribution. You build a whole world from pieces you brought with you.”

I pause, genuinely impressed. “Alright… fine. That was good.”

He grins. “Told you. Mateo Baker—available for all your curatorial sidekick needs. Rates negotiable.”

I was so proud in that moment, listening to my brother casually analyzing art. It’s not his world like it is mine, but he meets me there—and that’s the joy of being his sister. Then, I report back, “After visiting Zhou B’s, I went to Stussy’s and got those triple-decker cinnamon roll pancakes.” As if I heard some of Mateo’s inner dialogue, I add, “I know, I know, I’m supposed to be gluten and sugar-conscious, but I couldn’t resist.”

“Yeah, those are great. I understand,” he replies knowingly. “Actually, it’s serendipitous that you found that place. It’s Black-owned. Did you know that it’s one of the few Black-owned spots in Bridgeport because it used to be a place that kept Black people out because of redlining?” This establishment felt like the point of the exhibition: reclaiming sites of exclusion and fostering one of making, nourishment, and belonging for all people.

*Note: This conversation is not verbatim, but a compilation of chats, real and imagined.*

About the author: Chenoa Baker (she/her) is a curator, wordsmith, and descendant of self-emancipators. She was the Associate Curator at ShowUp, an adjunct at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and a consultant on Gio Swaby: Fresh Up at PEM and Touching Roots: Black Ancestral Legacies in the Americas at MFA/Boston. In 2023, she received the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art (AICA) Young Art Critics Prize.

Currently, she teaches African American Craft History at the James Renwick Alliance, edits with Sixty Inches From Center, Pigment Magazine, The National Gallery of Art, Boston Public Art Triennial, and The Corning Museum of Glass, and writes for Hyperallergic, The Brooklyn Rail, Public Parking, Material Intelligence, and Studio Potter.