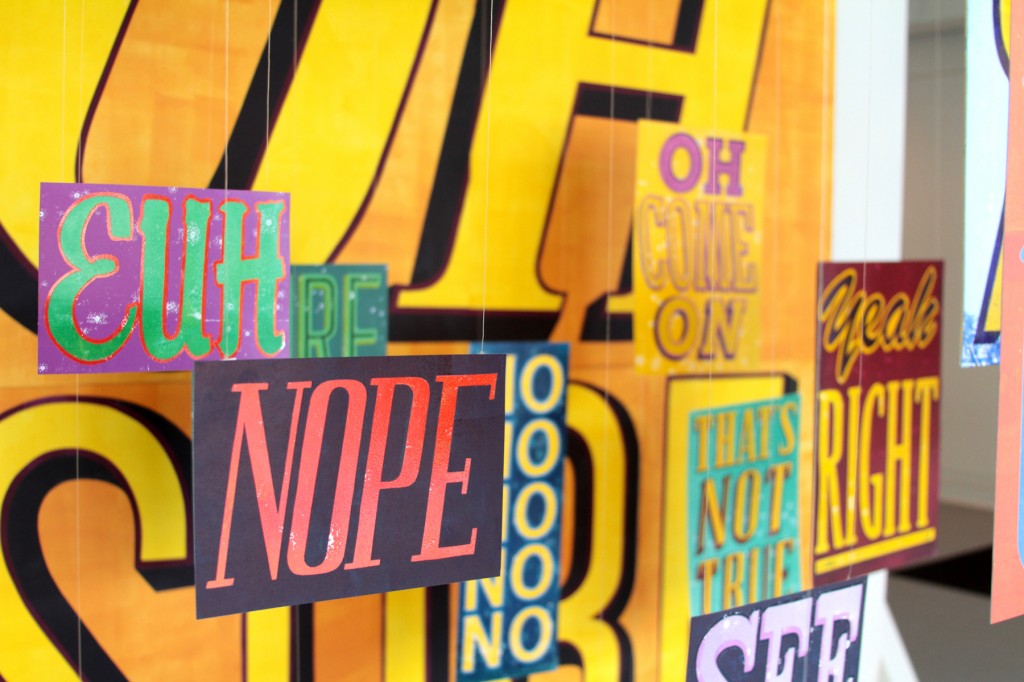

And The She’s Like/And He Goes, an exhibition at A+D Gallery,that juxtaposes text-based and sound-based art to expose the rich layers of the media and content. Chris Campe, artist and curator of the exhibition, recently returned to Germany after completing her Master of Art in Visual and Critical Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In this interview Campe sheds light on curating from abroad, the unique combination of artworks, German compound nouns, and the relationship of letterforms, text and sound in art.

Kate Korroch: First and foremost congratulations on the exhibition! Can you tell me a bit about your process in selecting the artists and their specific works?

Chris Campe: Thanks! I am very excited about the show – all the more because I moved back to Hamburg before it opened and I haven’t actually seen it yet!

The initial selection of the visual artists came about quite naturally – they are all my friends. I love their work and because we all use hand-rendered text in our images I felt that our work somehow resonated, and I wanted to see it all together in one space. Actually, Deb Sokolow wasn’t my friend yet, but like everyone else I really admired her work and wanted it to be in the show. So, I sent her an email and she immediately said “yes, sure, I’ll be in your show, why don’t you come by my studio sometime!”

I drafted a proposal and sent it out to a few galleries. A+D Gallery liked the idea of examining the audible aspects of hand-rendered text in art and when we started to talk about the show the idea came up to also include some sound-art pieces that sort of come from the other side and deal with the visual aspects of (language based) sound.

I don’t really see myself as much of a curator, but more as a fellow artist who took on organizing the show. I exhibit one of my pieces in it and the process of talking with the others about their work and the exhibition really had an impact on my own artistic work. When I first thought it would be great to see the work together, it seemed obvious to go and organize an exhibition myself rather than hoping for a curator to also like the idea and take on that task. Of course, it would have been super interesting if someone else had done it for me.

KK: Yes, the definition of “curator” does seem a bit tricky these days. On that note, as curator, what was it like doing the final installation from Germany?

CC: It was weird, and definitely a good exercise in not being in control. I went to the gallery with the artists a couple of times and we talked about what to put where and how, but I only made the final installation plan two weeks before the opening when I was already back in Hamburg. It was difficult to estimate remotely how something would look in the space just with the help of wall mock-ups made in Photoshop. I was not sure how precise the gallery needed the installation plan to be, so I specified half-inch-measurements for the positioning of the work. At some point Mark Smith (artist) said “that’s so cute!” so maybe it was unusual to give instructions to that point.

During install in early August I was expecting to get urgent transatlantic phone calls, but Megan Ross, the preparator for A+D Gallery, and her colleagues made some “executive decisions” about details that just didn’t look right, and the few questions they did have we clarified via email.

The advantage of not being there for the installation, besides avoiding some wrecked nerves, is that I will be able to walk into the gallery for the first time when I come back to Chicago in September and have a totally fresh look at it. I can’t wait!

KK: That will be a very unique view on your own exhibition. In your introduction to the exhibition you speak of four distinct players dictated by the title: she, he, the narrator, and the audience. You immediately identify the (literate) viewer as a performer in the exhibition. There is an immediate engagement because the viewer naturally or subconsciously starts to read. I think text, in a way, is more difficult to gloss over than an abstract painting, for example. Our brain naturally wants to dissect what’s there if the text is at all discernable. The same goes for sound, we can’t help listening. Is And Then She’s Like/And He Goes, in general, more accessible because the visual work in the show is composed of (mostly) readable text?

CC: That`s a great observation about an aspect that connects the visual work and the sound pieces in the show. I am not sure text is per se more accessible than, say, abstract images or images without text in general, but you are probably right that text like sound has a sort of “pull” that can hardly be avoided.

The intro for the exhibition catalog plays off of the fact that most of the work in And Then She’s Like/ And He Goes is really fragmented. To different degrees the pieces all tell stories and evoke specific situations, but it’s hard to pin down what those are so these stories, or the context of the text/image, depends on the viewer. In this show specifically this means that the text in the visual work resounds in the viewer’s mind and the sound-work conjures up mental images. In a way the pieces are completed only when the viewer sees them.

KK: You combine sound and text based pieces and their inherent connection. I especially enjoy the seemingly indistinct reverberations that force the viewer to think outside of discernible sound in works by Jeff Kolar, Jana Sotzko, and Elen Flügge. Can you talk about the relationship of sound and text?

CC: Most of the visual work already existed when I first started pulling together the show, but the sound pieces were developed specifically for this exhibition. I contacted the sound artists and talked with them about my ideas and then they developed their projects from there. I had in mind language-based sound pieces that quite literally do the opposite of what the visual work does – evoke visuals in the viewer’s mind through spoken language. I have not yet seen and listened to the final iteration of Jana and Elen’s and Mark Booth’s piece but my impression is that the sound pieces generally came out more abstract than what we first talked about. This is a good thing because it makes the entire exhibition more complex and less literal.

KK: The inclusion of the sound-art pieces definitely helps complicate the other work and actually think about the relationship of text and sound. I am also curious about the relationship of text and image, or the relationship between drawing and writing. Are my scribbled notes an image, text, a bit of both?

CC: I’d say your scribbles are text and image at the same time – much like the visual work in the show. It takes some effort to see the letters in the images as the arbitrary, abstract marks that they are. At the same time – like you said – if you know the language, or even if you don’t, it’s impossible not to read the text. Maybe if you don’t speak the language it makes seeing the text as an image easier, or maybe it is completely distracting because your attention is drawn towards figuring out what the words might mean. Either way, the content of the words adds to the image and distracts from it the same time and that’s what makes the image-text keep flipping back and forth.

KK: I keep thinking of this exhibition as an homage to the materiality and practice of the handcrafted—the trace of the artist’s hand. None of the text in your show is machine made, correct?

CC: Yes, none of the text is machine-made. That is partly due to personal preference, but in the context of this show my focus is the extra layer of meaning that the hand-rendered irregularities of the letters add to the meaning of the words. The traces of the handtakes away from the text’s linearity and its capacity to be a “transparent” vehicle of content. Those irregularities transmit something that would be hard to put across with the perfect shapes of neatly printed or laser-cut text.

KK: Language and audience accessibility was another thread I observed in And Then She’s Like/And He Goes. I know that English is not all of the artists’ first language yet most of the artwork, save for Anne Vagt’s, is in English. How was that choice made?

CC: Anne sometimes uses the English language, she spent some time in the U.S. (she’s the person who gave me the idea to apply for a Fulbright grant). But some of the work we chose for And Then She’s Like… happens to be in German. To Jana and Elen I suggested early on that it might be best to use English because the exhibition happens in an English-speaking country, but it was ultimately up to them.

The language-material I work with is mostly in English, because I just lived in Chicago for two years, but also because I am working with the offset between my mother tongue and the learned language, English. My grandma was a well of low-German proverbs and I have always been drawn to the conventionality of overused sayings, especially in low-German, a language I understand but hardly speak beyond those words of wisdom. In my current work I use very common American expressions –someone called it “non-language”– and even though I know what the phrases mean and how they translate to German, there is always a slight disconnect when dealing with them. For me their meanings remain a little “fuzzy around the edges” because I never quite know for sure all the connotations they carry and whether I use them in the appropriate context. Because they are so overused and almost devoid of meaning themselves, the context in which they are used becomes much more important.

KK: Speaking of which, Anne Vagt uses the word “Akquisetatigkeit” in one of her pieces. I could not find the definition online–do you know what it means?

CC: “Akquise” means “acquisition” in the sense of acquiring new customers or trying to get commissioned to do a job, and “Tätigkeit” means “activity” or “task”. It’s one of those famous German compound nouns. In German you can attach one noun to another to create a new word – pretty much endlessly. It often ends up sounding overblown and bureaucratic. “Akquisetätigkeit” is a good example for this phenomenon. It could just be “Akquise” because acquisition is already an activity or a task but then it would not be so strange of a word.

KK: If you were to curate a similar exhibition, working with the relationship of sound and text, to a very different audience—say, a non-English speaking one or even an audience who cannot read Roman letters—what would you do?

CC: Honestly, I have never been to a country that does not operate on Roman letters so I would try to do some more travelling first. If I could not expect the audience to read and understand English text the focus would shift toward the formal qualities of the letter forms and the sound in the pieces. Communicating the ideas of this show with the work of these artists would then be very difficult. I would come up with a different idea.

And The She’s Like/And He Goes includes artwork by Anne Vagt, Jana Sotzko & Elen Flügge, Deb Sokolow, Mark Addison Smith, Tony Lewis, Jeff Kolar, Chris Campe, and Mark Booth. The Closing reception for And The She’s Like/And He Goes will be at Columbia College’s A+D Gallery on September 6, 2012 from 5-8 pm as part of ColumbiaCrawl. The artists will be present for a gallery talk at 6 pm followed by a performance of Willhelm Scream by Jeff Kolar.

Featured Image at Top: Chris Campe, “Oh Sure” (Detail), 2012.

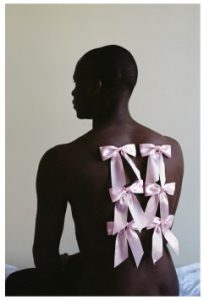

All photos were taken by Sophia Nahli. See more of her work by visiting www.sophianahli.com.