My bedroom started to smell like a marsh overnight: vegetal, damp, rotten. The 30-gallon planted aquarium on my desk was the source. Blue-green algae coated the glass walls, the spindly driftwood, and the thin layer of beige sand. This is an odd and frustrating development. I stabilized the tanks months prior and performed the same routine maintenance weekly, changing 10% of the tank’s water, replacing the CO2 canister and vacuuming the tank.

But winter is ending. The days lengthen and the overcast, gloomy weather recedes. Most mornings, a rectangle sunray illuminates the southwest corner of my room where my aquarium sits and slowly inches across until it lands on my bed, where I shimmy to the left and borrow a few more minutes of sleep. This subtle change in intensity, length, and brightness completely upends my tabletop ecosystem. To remedy or manage the issue, I track the arrival and departure of the sun each morning. I obsessively attempt to manipulate light, adjusting the automatic aquarium lights to work in tandem with the daylight, so that equilibrium returns and restores my algae-free aquatic garden.

While on a residency in coastal Maine, artist Ruby Que became attuned to the movement of light in their studio, too. Que developed a routine of recording the setting sun each day and projecting the image onto the wall during the night, recreating the illuminated shadow of the paned window as it slumps toward the floor and disappears in time for daybreak. They captured the subtle variations in the quality of light that would never happen again. It is an act of longing characterized by absence and idle time. Time becomes a source of pain, a measurement of distance from the object of desire—a lover, family, friends, or home. A banal routine of recording and re-projecting the sunset became a method of killing time, of feeling such absence less acutely by performing as if Que can recreate their exact experience from the evening prior. A reluctance to let things end. A nostalgia. The video itself also became one of the central images of Que’s exhibition Consider a Disappearance at the University of Illinois Springfield.

When Que emailed a still of Tired Light to Allison Lacher, who directs University of Illinois Springfield’s Visual Arts Gallery, Lacher recognized the shadow. She did the same residency at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation in 2022, a year prior. They are connected with the movement of light across space and time. Consider a Disappearance is characterized by such hauntings, coincidental and coordinated.

COME HERE I WANT YOU, a work fabricated from tempered glass and paper separated by magnets and mounted to the wall beside the entrance, offers a directive to audience members. The piece resembles a smartphone screen and reveals the last page of Ariana Reines’ Telephone when viewed from the right angle. Reines’ three-act play experiments with the unevenness and instability of communication mediated by telephones. The final act is a series of phone conversations that, when staged, takes place between three shadowed, faceless actors whose relationships are difficult to infer. Are they friends? Family? Lovers? The one unifying experience is that they are all frustrated by their inability to connect. The last two lines of the play read, “B: ‘Oh my god. Where are you?’ A: ‘I’m here baby. I’m right here,’” followed by a final stage direction, everything goes black. When I stepped away from the print and tilted my head, the words disappeared, replaced by a dark phone screen. This brief moment of connection felt thwarted or fleeting.

Impermanence emerges elsewhere in Que’s work. Que is a AV technician who compares their ‘day job’ to being a maintenance or caretaker who attends to the terminal lifespan of technology day after day. Projector bulbs always burn out, no matter the age of the projector. The image always fades. The room always darkens.

During the closing performance, Que pushes a projector around the room on a wire cart, using it to wash out other images with yellowish light or project the texture of celluloid film. But the film strip snags with a toothy, mechanical crunch and the bulb goes dark. The moment feels choreographed and punctuated, a built-in technological failing designed to enhance our sense of loss.

I recall the slide strips that moments before were visible on the wall—a lone figure walking on the beach (projected upside down), a photograph of partygoers beaming beside each other, and landscape stills. My memory recall extends the life of the image and embellishes it, remembering details real or imagined. In Bluets, Maggie Nelson writes, “On the other hand it must be admitted that there are aftereffects, impressions that linger long after the external cause has been removed, or has removed itself. If anyone looks at the sun, he may retain the image in his eyes for several days, Goethe wrote… ‘And who is to say this afterimage is not equally real?’“

When I imagine my aquarium before the algal bloom, I picture an aquatic, Edenic environment with white sand and pruned emerald foliage filling every crevice around the driftwood centerpiece. This is a wholly untruthful memory. It was, in reality, much less spectacular than the manufacturing of my memory. But the afterimage of it is so much more potent. It is unblemished and thus much easier to yearn after.

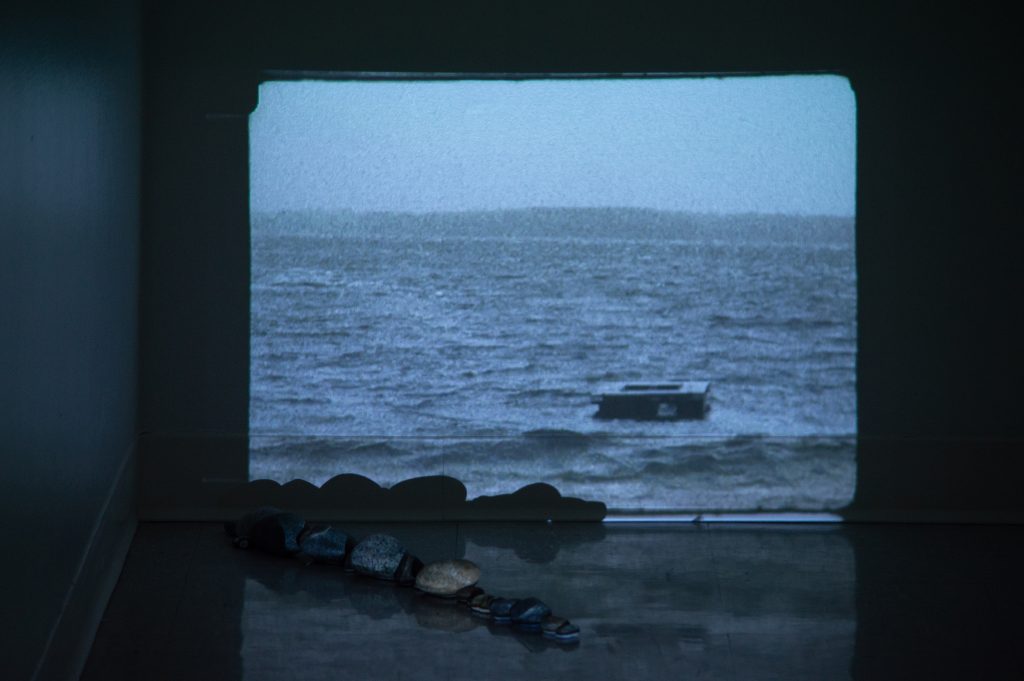

Over a midday glass of wine at Printers Row Wine Bar, Que explains they are often unable to develop their film for months. There is a forced distance to their process. In the far right corner of the gallery, Stranded is a digitized 16mm footage that Que took of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans while traveling. Que explains they were unable to differentiate between the two oceans while editing, but confesses that they felt more reflective while filming the Pacific shoreline; this ocean separates them from their home country. I understand. I frequently visit Lake Michigan and cannot help but remember that this body of water, which resembles an ocean, separates me from my family and hometown. And now nearly all bodies of water are imbued with the same sentimentality. Sometimes, I wonder if leaving means that I will forever be writing about something I have forgotten, that is now unfamiliar, that no longer exists. But I long for it anyway.

The artist Bas Jan Ader, who famously disappeared at sea while sailing across the Atlantic as part of In Search of the Miraculous, departed from Chatham, Massachusetts on July 19, 1975. The journey was supposed to take two to three months. He would’ve landed in England, then traveled to his final destination and homeland, the Netherlands. His boat was found adrift almost a year later. Ader’s body was never recovered. His students, perhaps unable to accept his disappearance, speculated that Ader was alive and well and started his life over. Neither his camera nor notebooks were recovered. His absence, and afterimage, became fodder for all kinds of miraculous fantasies and mythmaking. In his 2007 documentary on Bas Jan Ader, Dutch filmmaker Rene Daalder reflected on Ader’s journey homeward, “You can’t go home again, there is no such place after you’ve emigrated.” Que has not returned to Hong Kong since they left seven years ago to attend university in upstate New York. And until Que secures a new visa, they cannot leave the US without being barred from re-entry.

Que emailed me a link to the last few minutes of Wayne Wang’s Chan is Missing a few days after the closing performance. The 1982 film follows Jo, a taxi driver in San Francisco’s Chinatown neighborhood, who is trying to buy a cab license and pays his friend, Chan Hung, to facilitate the transaction. But Chan disappears and Jo, along with his nephew Steve, searches the city for Chan without luck, befuddled by the conflicting portrait of Chan and his motivations they uncover. Jo has a final monologue where he expresses his frustration: “This mystery is appropriately Chinese. What’s not there seems to have just as much meaning as what is there. Chan Hung is not there. Here’s a picture of Chan Hung, and I still can’t see him…”

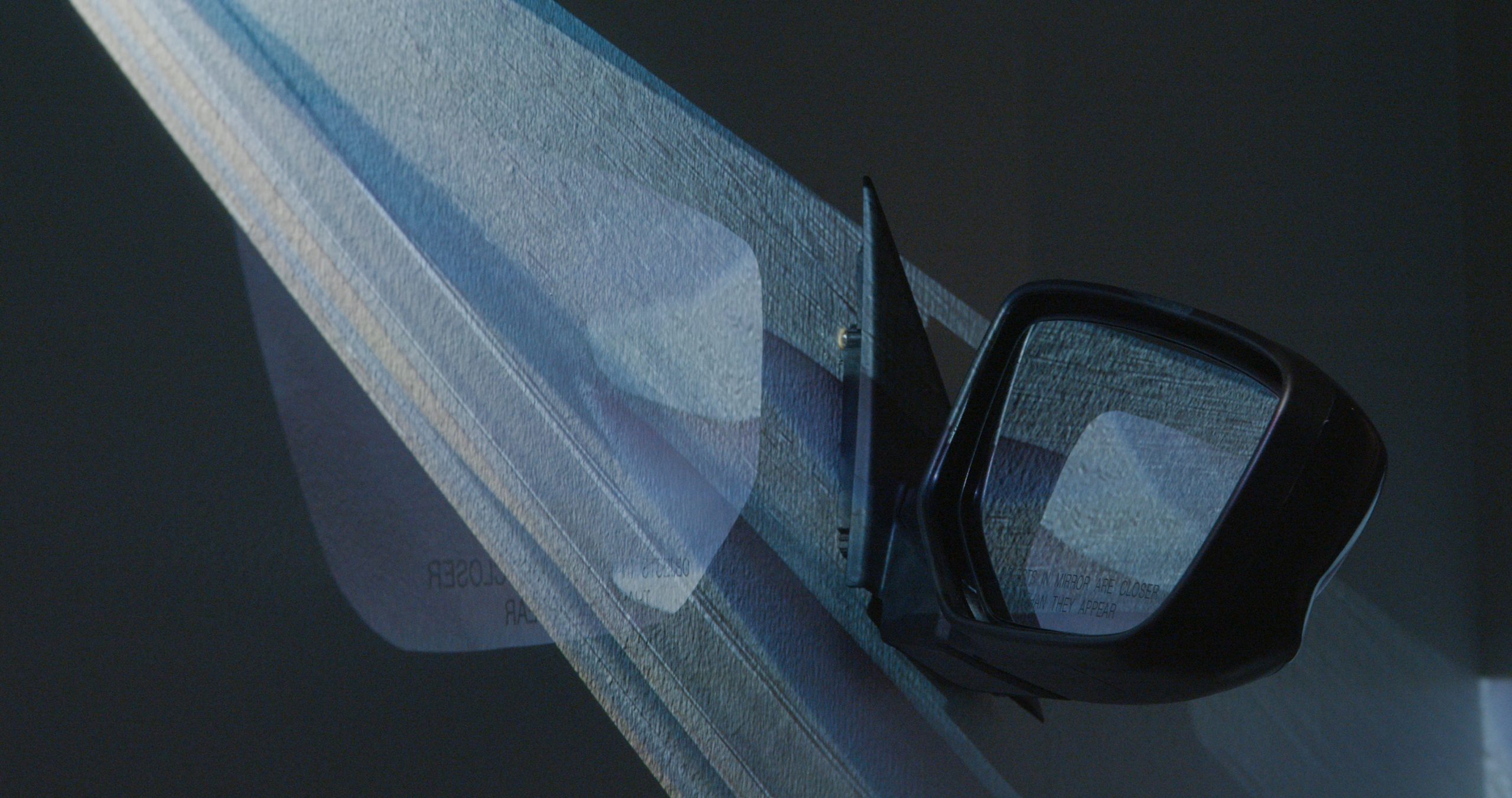

Absence is the most affecting and also the most difficult quality of Que’s work to comprehend, at least linguistically. Artist Bun Stout and I circle the topic on our drive from the La Quinta Inn and the University the morning after the closing. We attempt to describe our experience of Que’s work, both of us hedging our statements by saying, “I don’t know.” “Maybe.” This appears to be Que’s intention. Their videos are distorted by rearview mirrors, prisms, and mirrors. Familiar images become unrecognizable at first. As Ruby circles the gallery, armed with a flashlight or disco ball, I begin to recognize details, such as the illuminated shadow of the University’s gallery in Que’s site-specific video-work Nostalgia or the Midwestern landscape in Objects in Mirror are Closer than They Appear, a recording of the same route to the University we drove earlier that day. The images lack identifiable subjects beyond their documentation of quotidian patterns of light. But these spectral images mirror the loss of Bas Jan Ader or Chan Hung, whose disappearances become the site of meaning and myth-making. Their absence, this emptiness, contains as much meaning as their presence.

And Que attends to this perceived emptiness, noticing and capturing the smallest details with the kind of fondness often exhibited by the lovesick, those lonely souls who make a home out of nostalgia for an evening. A fortnight. A month. A year. A lifetime.

About the author: riley yaxley is most frequently a dinner party host, a fishkeeper, a homebody, a beach rat, a wallflower, a transgressor, a professional-email-sender, a progeny of “Midwestern Nice,” an amateur dancer, a flâneuse (if such a thing is possible), a glutton, an errant daughter who forgets to call her mom, a shameless navel gazer; and sometimes, she is also an essayist, memoirist, and art writer.