I attended the scent artist’s exhibition opening at Gallery 400 even though I lack a sense of smell.

My lifelong sensory deficiency induced a passive interest in scents, which was later encouraged by a close friend who collects fragrances and occasionally gifted me sample bottles they no longer wanted. I am drawn to unusual or overpowering scents because they are among the few I can detect; I purchased a bottle of Comme des Garçons’ CONCRETE, a creamy, woody perfume laced with metallic hints, while I was in San Francisco a few years ago and relished whenever someone complimented my smell, which another friend once described as a “lumber-yard-meets-airborne-concrete-dust,” elated that a commercially-produced fragrance could become a personal signature, like the open-ended “you” in a pop song. And when I was a teenager planning to study zoology at university, I considered my lifelong weakness an advantage because I would likely enjoy the stench of animal excrement and the variety of other unruly smells that spawned in the simulated habitats of zoos and aquariums simply because I could register them.

When I abandoned this career path, my poor sense of smell became an unremarkable characteristic I offhandedly shared with strangers during lackluster conversations as if this oddity would make me more remarkable. Now, I often avoid mentioning it because I worry someone might assume I am exhibiting a telltale symptom of COVID-19 and ignorantly flaunting my contagiousness.

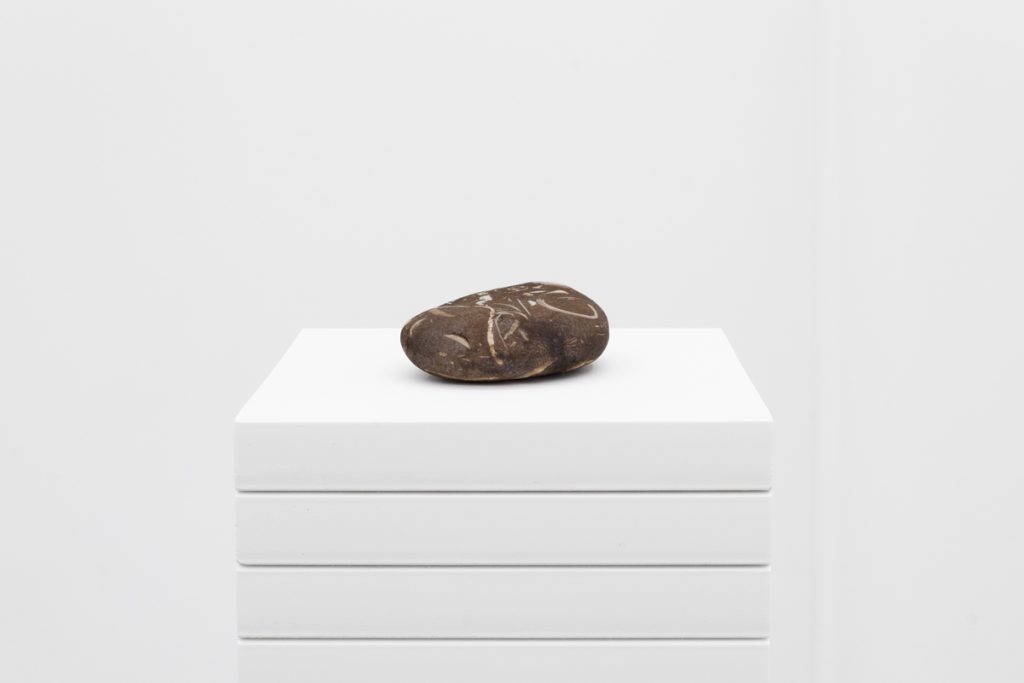

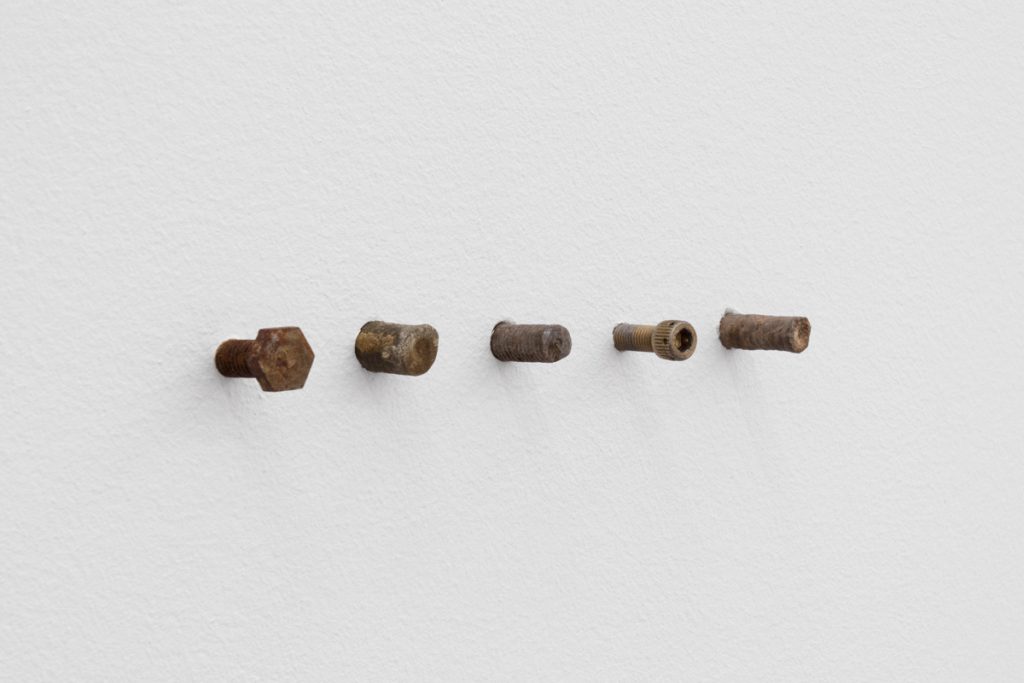

The same friend interested in fragrances recommended olfactory artist agustine zegers’ exhibition “(d)olor atemporal” at Prairie Gallery in 2024 because they knew I would be intrigued by the premise: zegers explored connections between ancient seabeds, modern petrochemical extraction, and plastic manufacturing, using scent to link these geological and manufacturing processes across time. Ultimately, I missed the show due to a flurry of work obligations and travel, but I admired zegers’ small sculptures on Prairie’s website—such as virtud petrificante (2024), transformación bentónica (2024), and temporeidad-extático-horizontal (2024), which repurposed used machine screws and fossils from ancient marine invertebrates by affixing them in short rows along the gallery walls, shavings of post-consumer plastics piled underneath the storefront windows, and a seabed stone containing fossil fragments with scent accords of microplastics, ocean debris, and seaweed resting on a white plinth.

In “(d)olor atemporal,” fossils signified the prehistoric plankton and algae that were buried underneath sediment and later transformed by heat, pressure, and time into petroleum and other fossil fuels. Both the fossils and plastics in the exhibition were morbid relics; skeletal remains of organic life that perished millions of years earlier during previous mass extinction events and plastic shavings piled together to form miniature landfills that remind us of the worsening human-caused climate crisis (a 2024 report from the World Economic Forum estimated an additional 14.5 million deaths from this crisis by 2050) and the near permanent contamination of natural environments by microplastic. zegers skilfully reimagined “ancientness” itself by demonstrating that these 60-million-year-old fossils are materially reconstituted as consumer plastics, whose glacial decomposition rate guarantees they will become artifacts of the Anthropocene. The long life of these plastics gesture toward an inconceivably vast future bookmarked by mass extinction. And between these geological eras? Humanity itself.

Not having experienced the show in person, I could not fully understand the scent aspect of the art. Yet, I wondered what I was really missing, and how essential it was to the premise of the art. Why scent? What effect would these accords of microplastics, seaweed, and ocean debris have on a gallery goer and their experience of these materially dependent artworks?

Despite never experiencing zegers’ scent-based work in person, I continued to admire their work through social media and later recalled “(d)olor atemporal” while listening to “Ten Minutes with Rachel Herz: On Smell,” a short podcast produced by MoMA Magazine. Herz, a neuroscientist who specializes in the science of smell, described the amygdala-hippocampal complex, which is a part of the interconnected brain structures, including the olfactory bulb, where the conscious perception of smell takes place, as well as the perception of emotions, memory, and associations. “No other sensory system has this direct and co-opted neuroanatomy where both a sensation is being produced and consciously experienced, and our ability to experience emotions and memory is also happening,” she explained, meaning smells consistently evoke an emotional response.

Through their use of scent, zegers was able to conjure layered memories and emotions, intrinsically enhancing and complicating each individual’s experience of and associations with these accords, whether they were repulsed by, attracted to, or ambivalent toward the sweet, chemical smell of plastic or the fishy stink of seaweed; zegers made petrochemical extraction an emotional affair. I remembered a classified ad I wrote searching for someone to visit zegers’ exhibition with, titled: Smell Ancient Life With Me? Perhaps I hoped to imbue these geological epochs with my infinitesimal human memories, the start of a new friendship or flirtation.

After missing zegers’ 2024 exhibition at Prairie, when their latest exhibition, “A toxin threatens, but it also beckons” at University of Illinois Chicago’s Gallery 400, was announced, I resolved to attend so I might finally experience their scent-based work. The title of zegers’ exhibition is a line borrowed from theorist Mel Y. Chen’s 2011 essay “Toxic Animacies, Inanimate Affections.” In this essay, Chen offered different examples of how human-generated toxins are experienced by nearly everyone, albeit most often by people living and working in U.S. poverty, or factory workers in China, Southeast Asia, India, Mexico, and so on—in order to question how so many of us can encounter this toxic world as benign or pleasurable and ultimately attempt to refigure toxicity as an extant queer bond that might unify people affected by toxins (read: everyone) and the inanimate objects that contain such toxins.

The second verb of this eponymous line from Chen’s essay caught my attention: beckons. Meaning “to summon or signal typically with a wave or nod” or “to appear attractive or inviting,” beckon implies toxins possess seductive qualities, including, I imagined, intriguing fragrances, like a carnivorous pitcher plant that attracts prey by replicating floral or fruity odors. Scent, and its accompanying associations, can also be a misrecognition.

In late September, I arrived promptly to the opening with a friend in tow. We started to read the wall text and were momentarily confused before we realized A toxin threatens, but it also beckons was one of three solo exhibitions accompanying Finnegan Shannon’s “Don’t mind if I do,” which brought to life Shannon’s lifelong fantasy for a show that met their access needs. My friend and I admired the elliptical conveyor belt in the central gallery space. We sat on opposite ends of the conveyor and inspected the series of slowly circling objects: bundles of multicolored yarn, a compact mirror, a house-shaped tissue box, a fragrance bottle with tester strips, and more.

As I walked along the length of the conveyor belt, zegers approached me and introduced themself. They were wearing a black button-down shirt cut into asymmetrical strips in the front. We made small talk about a mutual friend of ours who lived in New York, and whom I had a studio visit with earlier that afternoon. When I suggested I would find their work in the space, they offered to prepare a fragrance tester strip for me to sample, their scent accompaniment for both their exhibition and Shannon’s. I accepted and waited while they prepared the tester strip. I held it to my nose and was able to detect a faint smell through my KN95 mask. zegers encouraged me to briefly remove my mask so I might appreciate it properly, and I obliged; the scent immediately reminded me of pink, rubbery plastic, some childhood souvenir won from an arcade or purchased from one of those toy vending machines that used to live near the entrance of the supermarket alongside coin-operated horses and shopping cart corrals.

I excused myself from our conversation and walked the length of a hallway extending from the main gallery space to search for their work, occasionally holding the tester strip to the fabric of my mask and inhaling deeply through my nostrils. Other memories associated with the smell of plastic resurfaced; when I was a child, my siblings and I regularly filched odd bits of plastic from around the house to use as props in our imaginary sandbox games: thimble-sized caps from my father’s Pepsi bottles, serrated blue rings taken from the necks of 2% milk cartons, and multicolored shards of broken sand castle buckets bleached from exposure to the sun. Like many children, I often put these pieces of plastic into my mouth, enjoying how the plastic resisted before eventually yielding to my bite, like the child in Chen’s essay who licks a lead-contaminated toy. I could recall the taste of these plastic fragments even years later, slightly anesthetic yet sweet, like the aftertaste of a sugar-free soda.

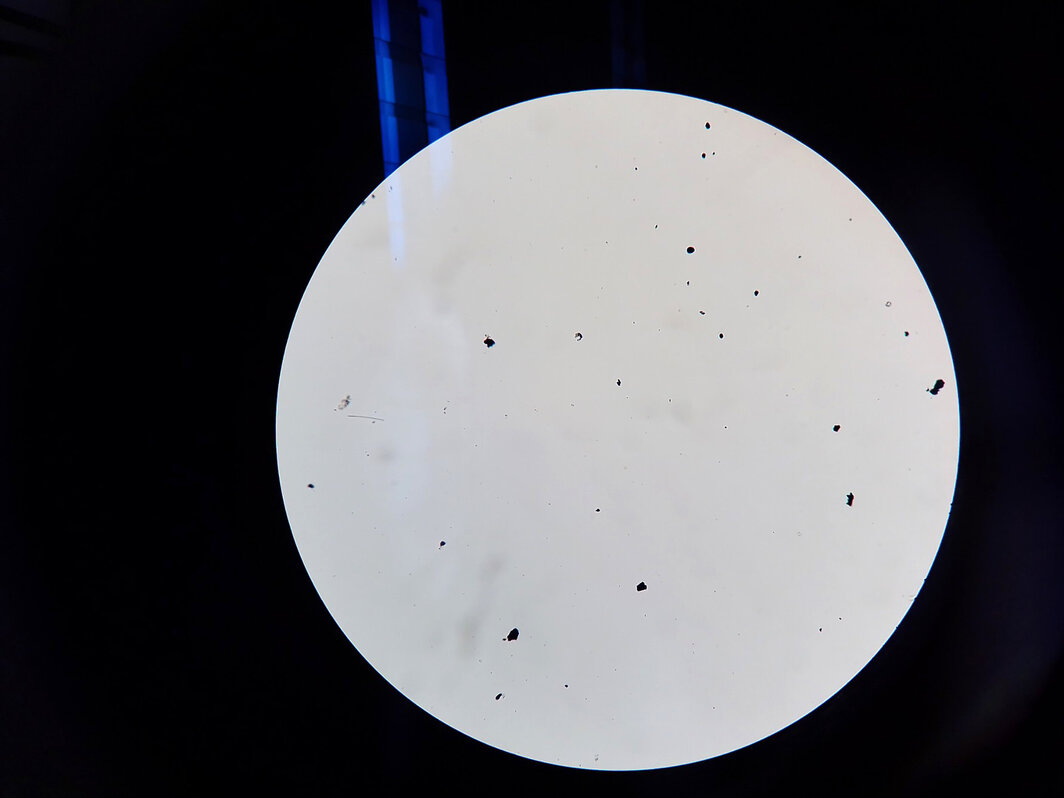

When I entered zegers’ exhibition at the end of the hallway, a small alcove with two windows overlooking a dry cleaners and parking lot, I was unsure whether there was any artwork on view, even though there was gallery text on the wall demarcating A toxin threatens, but it also beckons from the previous exhibitions. And then I noticed the small, opaque polymer puddles splattered on the windows resembling glue traps; however, instead of the corpses of tiny flying insects, the rubbery material was littered with similarly morbid fragments of microplastic.

Titled poli.etilena (2025) (read: polyethylene, or the most commonly manufactured plastic used in packaging), these oblong splatters shrink the physical scale of plastic’s presence in our lives and recast the detritus of its decay as a window decal. Since 1990, human consumption of microplastics has increased sixfold, with the average person ingesting at least 50,000 particles a year and inhaling a similar quantity. poli.etilena presents microplastic pollution as an unremarkable ornamentation we might otherwise overlook if not otherwise alerted to its presence by the gallery text.

zegers other work inter.densidad (2025) is similarly visually understated: More than a dozen white bottle caps are displayed along the length of both gallery walls. Mounted slightly above hip height, these found object sculptures require me to bend over in order to smell the plastic accord they are filled with, the same fragrance available on the conveyor belt in “Don’t mind if I do.”

As I continued to think about zegers’ work, I returned to an early passage from Chen’s essay, where they write: “A toxin requires an object against which its threat operates; this threatened object is an animate object—hence potentially also a kind of subject—whose ‘natural defenses’ will be put to the test, in detection, in ‘fighting off,’ and finally in submission and absorption.”

zegers’ inter.densidad are petri dishes where we might observe our own queer bond with petroleum and its byproducts, which pervade all aspects of our lives, including our own bodies as infiltrating toxins. In this context, Chen and I use queer to describe a type of relationship considered “forbidden” or quite literally “toxic” and damaging—to insist the ubiquity of plastic pollution means we all intimately experience this toxic material because of our porousness, ingesting and inhaling microplastics and excreting them as smaller fragments. Like lovers, we leave intoxicating marks on and reshape each other.

While I enjoyed how zegers’ work drew attention to our intimate relationships with toxic materials, I wished they had assumed the role of artist or educator rather than recondite scholar and explicitly addressed the biopolitical implications of our exposure to petrochemicals, perhaps through more didactic wall text or accessible descriptions of the materials used in their artwork.

Weeks after my friend and I attended the exhibition opening at Gallery 400, my friend found the fragrance tester strip with the inter.densidad plastic accord in their shirt pocket and returned it to me. While writing this essay, I occasionally lifted the tester strip underneath my deficient nose in order to experience scent again, even though its faded potency made it more difficult for me to detect. I tore the strip in half, hoping to agitate the remaining scent, and inhaled deeply, surprised to discover it evoked the same fond memories of plastic, the misremembered, saccharine nostalgia for childhood summer afternoons even as I realized the artifacts populating these scenes—the broken shards of plastic, bottle caps, or animal figurines purchased for cheap from a toy vending machine—would outlive me for more than half a millennia.

A toxin beckons, but it also threatens, reminding me of Mel Chin’s 1991 short-lived Revival Field, a conceptual land art project built atop Pig’s Eye Landfill, a superfund site near St. Paul. Chin partnered with soil remediation expert Dr. Rufus Chaney to design and stock a garden with “hyperaccumulators,” plants capable of growing in and extracting heavy metals from contaminated soil. Chin’s Revival Field confirmed the potential of “phytoremediation” as a low-tech alternative to costly and unsatisfactory methods for extracting contaminants from soil and groundwater. Chin and Chaney discovered pennycress, a member of the cabbage family, absorbed significant amounts of cadmium, a human carcinogen. Like zegers, Chin responded to human-generated toxicity through Revival Field, exploring the porosity of various plants to these heavy metals; Later, these hyperaccumulators could be burned in reclaiming furnaces, generating metal purer than mined ore (and, of course, climate-damaging carbon dioxide). These plants become a brief vessel for the reconstitution of these metals from one location to another before perishing.

However, unlike Chin, zegers does not offer a remediatory method for dealing with the catastrophic toxins produced by the petrochemical industry, perhaps indicative of an underlying cynicism about such cleanup efforts. Potential bioremediation methods, including a type of zooplankton found in marine and fresh water that can ingest and break down microplastics, don’t offer a sort of alluring deus ex machina for human-generated plastic waste: these zooplankton split the particles into thousands of smaller and potentially more dangerous nanoplastics that are introduced back to the global food chain and eventually make their way back to us. A 2024 University of New Mexico study found microplastics in the placentas of all 62 babies tested. We are now born toxic.

I pressed the torn scraps of the fragrance tester strip zegers prepared for me and inhaled deeply, comforted momentarily by its faltering sweet scent, which evoked again this layered bodily archive of memory and emotion that now includes scenes from my childhood alongside memories of walking through zegers’ exhibition with my friend and later writing this essay at my Ikea desk, wondering how so many of us continue to see our relationship with plastic as benign or even pleasurable. Is it possible we could feel affection for these man-made toxins for whom we find ourselves temporary hosts—that we envy their nearly immortal lifespans, which far exceed our own, naively hoping this quality might contaminate us too?

About the author: Riley Yaxley is most often a dinner party host, a fishkeeper, a beach rat, a flâneuse, a glutton, a dancer, a delinquent daughter who forgets to call her mom; and she is also a writer, editor, and arts administrator.

The middle child of seven, Riley was born and raised in a Detroit suburb and currently lives in Chicago on the stolen land of the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa peoples. She earned her BA and MA in Writing, Rhetoric and Discourse from DePaul University, was a member of the 2023 Muña Art Writing Residency cohort, a 2025 ACRE resident, and participated in the 2025 Tin House Winter Workshop. Her work has appeared in Sixty Inches from Center, Dopamine Books’ CLOWNS, A Great Gay Book, and Catapult. She is currently an editor for Sixty Inches from Center.