I grab a knife and puncture a small slit into what I consider to be the top of a watermelon. The knife stands erect, and I push it down as if it is a lever as it smoothly slices the fruit. I hack up the red, juicy contents inside, and begin to pick out tiny black seeds and discount them into a pile. As a kid, I worried that if I accidentally ate a seed, an entire watermelon would grow inside of me. I laugh about this fear now, but I can’t say that it was entirely irrational. This is a fear, or an intrigue, that most of us have experienced at least once back when we were brand new to the world. Even with our brains still folding and our understanding of the world expanding, we recognized the power and potential of a single seed.

The exhibition Seeds of Resistance at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, curated by Steven L. Bridges, features 12 globally diverse contemporary artists. The title alone makes me imagine rows upon rows of tiny seeds standing amongst one another working together as a militia. My next consideration is, who is on the other side of that battle field? Seeds of Resistance brings together the work of Antonio Ballester Moreno, Mel Chin, Beatriz Cortez, Dornith Doherty, Johannes Heldén, Håkan Jonson, Dylan Miner, Santiago Montoya, Claire Pentecost, Vivien Sansour, Jackie Sumell, Shinji Turner-Yamamoto, and Sam Van Aken in order to highlight the intrinsic relationship between humans and plants. There is also an emphasis on the concept of a seed’s life; seeds themselves are not only physical vessels of genetic information that spark plant growth, but can also take the form of a thought being planted into someone’s mind.

Stepping into the main gallery at the Broad, the first work I am confronted with is Antonio Ballester Moreno’s Live the Free Fields. I am looking at what appears to be hundreds of ceramic funghi sprouting up from the gallery floor in the shape of a circle. It is reminiscent of the sensation I feel when on a nature walk, and nearly stumble onto a vital piece of the ecosystem; there is a moment of panic at my realization that I almost bulldozed an essential player in the cycle of life. This moment of panic serves as a reminder that not all powerful and necessary elements of our environment are in plain view straight ahead, and most are, in fact, at your toes. Moreno’s piece grounds me into the soil, plants me into the exhibition. I begin to think about the thousands of tiny seeds that are underneath my feet at any given moment. The walls of the Broad begin to fall around me and I start to wonder what was here, what was on this soil, before this building was constructed.

In many ways, seeds serve as a container. A seed can be thought of as a time capsule in that they can be taken from one era, preserved, and planted in another. The oldest seed in the world, a date palm seed, is 2,000 years old. Consider the persistence required of a seed to last that many years. Seeds are one of the few things on earth that have a level of tenacity that allows them to exist that long. A faculty member from MSU, William J. Beal (1833–1924), started an experiment in 1885 called The Beal Seed Viability Experiment, which was created in order to find out how long a seed can remain viable, and has gone on to become the longest ongoing scientific experiment in history. Seeds of Resistance finds its roots in this experiment that started on the very same soil that the Broad now stands.

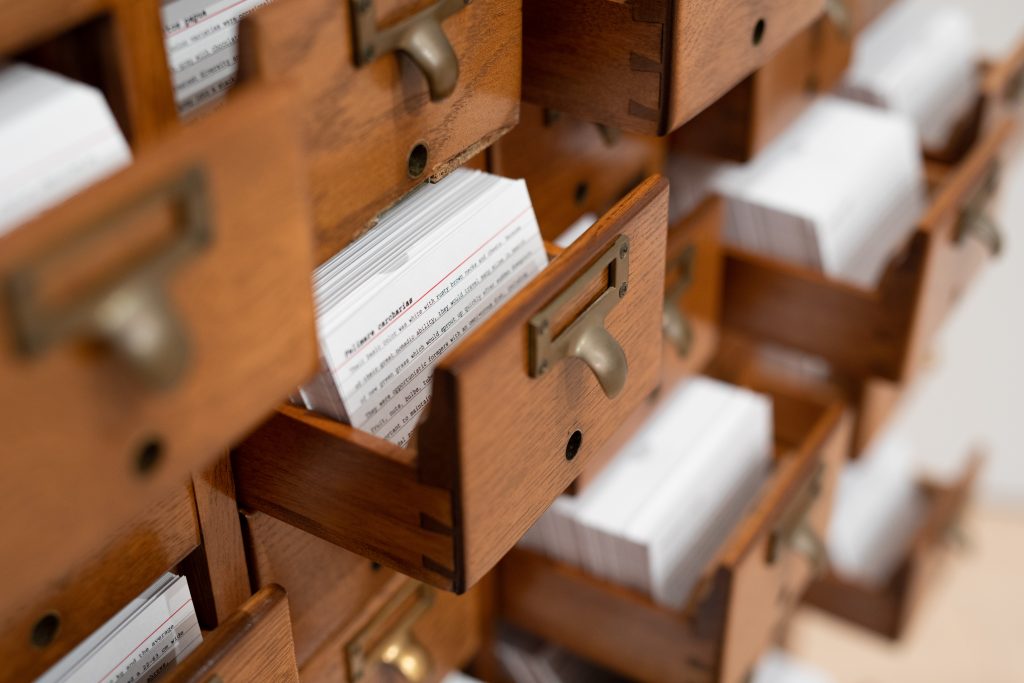

Rounding the corner into the second room of the gallery, I see a large chest full of 60 small drawers. Filled with stacks of notecards, a few drawers are pulled open haphazardly as if someone were recently rummaging through them. The piece, titled Encyclopedia, was created by collaborators Johannes Heldén and Håkan Jonson. Using artificial intelligence, the duo created a database of future species that have gone extinct, with the notecards reading the individual encyclopedic entries for each species. As strange as it is to conceptualize this enormous number of species going extinct, the reality is, we are not far off from experiencing this level of extinction ourselves. Seeing the seemingly endless stacks of note cards organized into each drawer is chilling. It is easy to ignore large figures, like the one-million species that face extinction today, but visualized in this way, the reality is sobering: future (and not too far in the future) generations could easily have a chest full of drawers exactly like Encyclopedia, only full of the species we know and love today.

A seed can also serve as a capsule of genetic and cultural information. In the middle of a room, there is a long wooden table with benches inviting viewers to take a seat. The table represents a piece of a larger project, The Palestinian Heriloom Seed Library, by Vivien Sansour. This project’s mission is to bring light to the histories surrounding Palestinian seeds by introducing them in a dinner table setting. Sansour invites guests to the table with the intention of cultivating conversations reminiscent of a dinner with loved ones. Rather than passing around dishes of food, the viewer can pass around stories from Palestinian farmers, artists, writers, foragers, and survivors, in the form of postcards. Each postcard connects to a different seed, and through this interactive piece, viewers can learn about both the genetic and cultural significance of that specific seed. Pairing the seed with a person’s story helps develop the idea that seeds have tremendous value in both furthering a healthy ecosystem as well as the symbolic power of planting a mental seed in others by sharing our life experience.

Seeds of Resistance works as an ecosystem in its own right. Explorations of biodiversity, sustainability, pollution, and other environmental concerns reverberate through more than just the seed. Also included in this exhibition are mineral-based work, such as Shinji Turner-Yamamoto’s Pentimenti #74, sculptures made from soil, like Clair Pentecost’s soil-erg, and work that actively preserves precious seeds, such as in Sam Van Aken’s Herbarium. Additional works in the exhibition comment on air pollution as well as the future of our planet. Though the emphasis relies on seeds, this show encompasses the complexities involved in biodiversity by incorporating works that touch on these other elements. Seeds of Resistance also succeeds in providing a global perspective on these issues by including artists from vastly different geographic and artistic backgrounds. The strength of this exhibition relies on the many different voices and perspectives being invited together to offer up their unique experiences. Biodiversity and ecological preservation are complex topics that affect every corner of the globe; there is no place on earth that is safe from the creeping doom of climate change. However, when artists are given a space to apply their lived experience as well as their creative take on the environment, there is hope for change.

Seeds of Resistance is one view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum through July 18, 2021.

Featured image: Seeds of Resistance installation view at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, 2021. Photo: Eat Pomegranate Photography. Image courtesy of the museum.

Ally Fouts is an artist, designer, and writer living in Chicago. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Art, Media, and Design from DePaul University. More information surrounding her artistic practice can be found on her website.