Featured image: Exhibition of view of small and medium-sized framed and illuminated artworks. Photo by Robert Chase Heishman, courtesy of table.

In education, the subjects that are deemed required and the subjects that are offered as electives directly reflect and influence what we value in our society. In the canon of western art history, the prescribed narrative has been defined by white men and their ponderings on art that reflected their experience. Those opinions have dominated the topic (and curriculum) for centuries and, as a result, our modern view of art history as a subject is skewed in a way that posits the works of some vastly above the works of others. In the show Soft Power Hard Margins at table, artist Nyeema Morgan layers reference upon reference to present the hierarchy very literally.

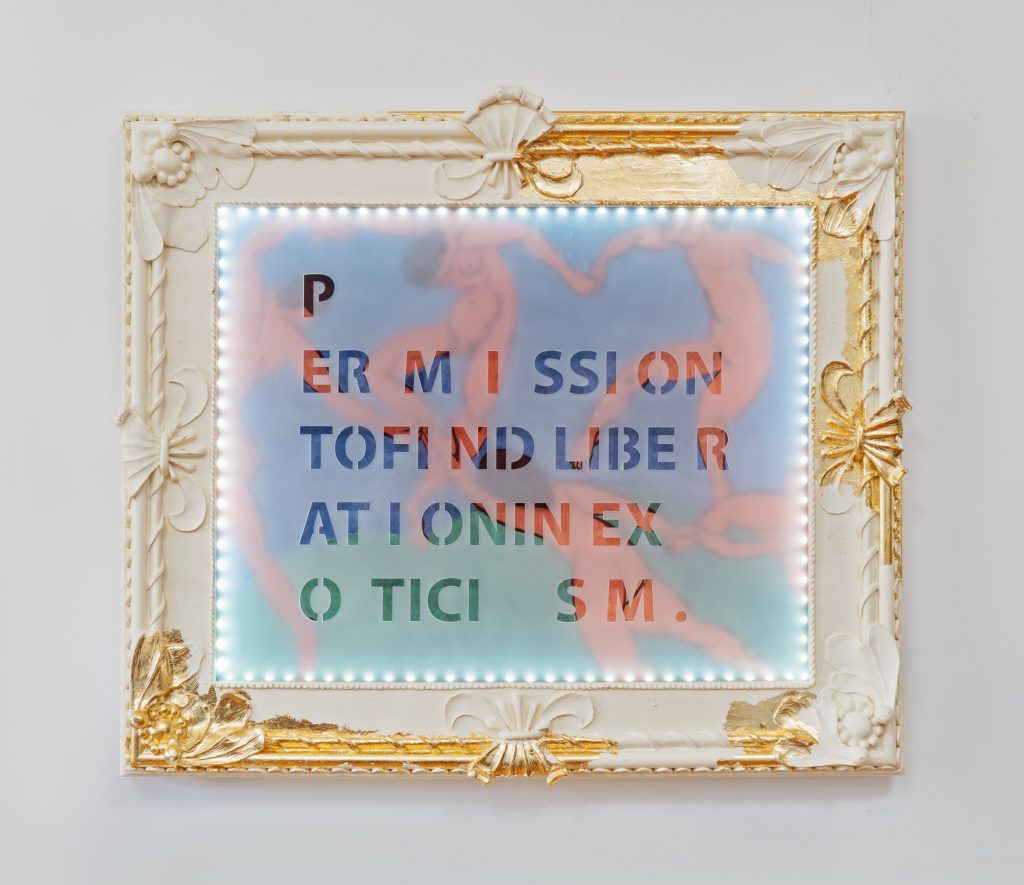

The pieces in the show appear as individual framed works, but they are actually a single series of sculptures. Comprised of 35 notable images of art, each piece is mounted in ornate white frames and illuminated internally by a border of twinkle lights. The frames that house the images are neoclassical in style yet artificial in production. Cast from resin, the frames are gilded, but not in the traditional sense. Instead of gold leaf just appearing on the frame, the artist has applied it in random bursts on the plexiglass, the frame, even the gallery wall. Placed over each image is a sheet of translucent plexiglass displaying a different message that grants the viewer certain permissions; permission to self objectify, permission to acknowledge the horror of everyday existence, in a sense, permission to engage with the pieces on a personal and real level.

Morgan describes the messages etched into each sculpture as “a reflection of the various internal permission we grant ourselves.” Each work proclaims something different. “Permission to challenge the power dynamics of class and gender” is written over Manet’s painting of Olympia and her Black Maid. We’re granted “permission to find liberation in exoticism” by the nude red bodies of La Danse by Henri Matisse. We have “permission to express political dissent” in Guernica by Pablo Picasso. The precise stencil-like lettering contrasts against the erratic spacing and misspellings, making them seem almost meme-like. Some of the messages are easy to read, others are at first glance nearly indecipherable, requiring a deeper engagement to understand the literal “meaning” assigned to the work. The show is ultra-modern in that sense. The current generation of creatives is no longer satisfied with what has been dictated to us for years and years. Through the proliferation of art history memes, more and more voices have been contributing to the conversation about art, and by doing so we are encouraged to reflect upon the meaning and value that has been assigned to the great works. Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. seems practically quaint compared to the way art is manipulated and shared online.

The pieces are hung in the small gallery salon-style and are presented in three different sizes. The larger sculptures are all images of the most famous, “greatest” works of art. The mid-sized works are slightly less famous with the smaller works being the most obscure. The star power of the most well-known images radiates through the larger works, even when hidden behind gold leaf and foggy plexiglass. The largest works featured included pieces like Mona Lisa, Starry Night, The Scream, and David–all so famous the name of the artist isn’t necessary for their identification. These monumental images take up so much space in the small three-walled gallery, a reflection of their outsized influence in western art history. As visually stunning and obviously masterful these prodigious pieces of art are, it’s a disservice to reduce art history down to just these works.

Morgan takes cues from different parts of art history by way of her neoclassical style frames, the ultra-modern laser cut, and the broad range of historical artworks she pulls from. The work as a whole is a lot to take in, as each piece is layered with reference upon reference. I consider myself relatively well versed in art history and yet there were plenty of things I did not recognize. I was very much struck by the take on Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World. Here, Morgan grants us the “permission to be nostalgic for American provincialism.” As a native midwesterner, I loved the message, but I was unable to place the work it was referencing when I saw it in person. Attempting to comprehend all of the messages in the work made me feel like an art history student again, looking at an image and desperately trying to grasp the meaning or understand what my professor was saying. The pieces are intimidating in that way. The multi-layered works both large and small demand that they are assessed in their entirety. Continued examination unveils the detailed concept that pulls you in; the sum greater than the individual pieces.

Jen Torwudzo-Stroh is an arts and culture professional and freelance writer based in Chicago, IL.