These poems were selected through Sixty Literary, a biannual call for literary writing from writers and artists based in the Midwest. You can learn more about Sixty Lit’s inaugural call for writing here.

A mobilization in five parts

Part One

I first meet you in class. What’s a bomb here or there, the professor says,

lacerating the question mark. You unfold the fist and place a sweet treat

in my hand. I unfold the shirt I had just folded and we study for the test

over the phone. At the end of the term I turn in the book with one page

missing. It’s ok, the TA says, it’s just someone with smoke on their face.

Part Two

After your funeral, I am unprepared to clean your apartment. Figurines,

your father’s cufflinks, photos, records upon records, books, clothes,

dishes, cups from every diner in the Midwest. I find the notes from your

attempted translation of the Iliad into Arabic. Hundreds and hundreds of

obsessive pages. The same Achilles and Hector scene over and over again

refracted through redacted words, lists of possible synonyms, annotations,

tea stains, food, blood on pages, dirt from shuffling feet. What can I do

with all this but pack it into a box and find everyone in the living room

crying? The quiet of us all watching each other is a translation of desire.

Part Three

There’s one with Achilles never actually killing Hector, instead both of

them walking away from each other into lives they were meant to live.

In the corner of the page you have written: no bodies dragged through the

street, no occupations. Another page: Achilles touching Hector’s face

saying my people will only sing my name if you die and King Priam

saying I want another name that doesn’t weigh more than my son’s body.

One page is in the form of a headline: tomorrow we will be burned,

tomorrow we will be news. So much longhand written as dialogue: You

must die for me to exist. I am Achilles because you are Hector. I exist

because of your body in the dirt. Please today let us be unfolded, unopened,

unbent corners. You and I have the same mouth. There’s one where

Andromache stabs Achilles in the arm with a dagger and backs up like a

wolf, blade out to protect her husband’s body. One where she is taunting

him: occupier, colonizer, annihilator. Throwing rocks at his soldiers. One

where her oldest child shouts from the balcony to him, You are not the

hero of this story. One where there is no stronger and tougher warrior, but

a cover up of the army’s murder. One ghazal where Achilles trades his armor

for a horse and with Hector rides to Mount Ararat to ask for the moon’s

blessing. One where NO is written over the printed text over and over.

Part Four

The translator explains we are taking one bus to the bomb site and I think

of the things you can’t hold with two hands. We move towards the rubble

and kneel in prayer. The way the priest and the imam ring the bell for us to

follow, you would think they were raising a garden of spirits. It’s like a

dinner time bell I tell you and you say oh kiddo the world has too many

poems about grief so I start writing about the bones with each name carved

into them. I mistake the translation and hear something about songs in

heaven but then realize she is reciting a list of names with yours on it.

Today is a dose of aspirin maybe half a tablet easing the pain for a few

hours. The dead find us the way you can only find things incongruous to

the landscape, like an open hand sitting in an absent fist. I want to tell the

priest and the imam they are less instruments of god than an instruments

of gravity not reading prayers in front of us, not asking for god’s love, but

for something closer to the ground. Sometimes I think grace eludes us

because gravity keeps us from our desire to finally float away and yet here

we are anchored, shaking the soil from our clothes in this rubble. Some of

us are gifted justice in the smallest box, no ribbon and no wrapping, just

warm earth and bones, and one more chance to hold you again.

Part Five

I pull my coat tight and extend hands in both directions reaching for other

hands, feeling twenty-seven bones in each as we move forward through

the police barricades, one willful step at a time. Before we are arrested and

thrown like so much unclean laundry onto the bus we offer a counterpoint:

an assembly of quiet faith. For a few hours we are framed as agents against

the government and almost call out to god. There are prayers in the air. They

are crackling drumbeats against our feet, gathering up again to walk in your

name. Someday, I will walk back where the bombs hit you and fold this poem

into the smallest box, neatly tucking it back into the earth.

.

An archive of seven movements, remembered, during your funeral procession through the city

You are taught as a child to recite the ocean’s prayer

Bless empty vessels after a storm

Bless the land for breaking promises in my arms

Bless the ships when they hear my voice and their faces awaken

Bless my waves when we slow dance to your destination

Bless water in the lungs of those turned away from arriving

Bless the moon in my arms laughing when the day is over

Bless my body at midnight, endlessly with and without moons

Your life is being measured in small rooms on stolen land

As soon as you can be seen as an adult body,

you are suddenly a danger in every port

After your assassination attempt your wife asks me

how could anyone with gentle hands fight a storm?

Your true name takes flight when chanted in the streets,

two syllables opening and closing like wings

Only you can sing a song to facilitate a city

to unclench its fist for the briefest of moments,

only you can tell us we are capable of such a thing

In your speech on the steps of parliament you say

when I come back, I want to be the ocean

perfectly full and empty

desired and misunderstood as only a body of color can be

.

Tandoori with spicy yogurt

Chicken

I had a dream about my auntie cooking again.

She said I want someone to paint my hands so I can see

them at rest at the exact moment when I am not

trying to hold the world with both hands, someone to paint my

hands, hands made by hands.

I thought about how my father held my hands

and told me he can’t remember the sunsets in Dar es Salaam anymore.

Water

I go to the store on Lake Street because they have the ginger chews I love

and because owner will always take time even from his favorite soap opera

to talk to me, awhile.

You want one for your car, he asks, nudging me a box of American flags.

Take one. These are the times we are in, brother.

We came here to bargain for our lives under a second sun.

His wife shouts to me from the aisle in Urdu.

I could try to translate it for you, but it wouldn’t make sense.

She shows me the bin of umbrellas

and says we arrived at an imaginary line in the soil that may have been a border

and fell on the cities like rain.

I tell her about my father, who never left the house in anything less than a button-down shirt,

and the angry woman at the bus stop yelling at us to speak English,

and how he shrugged off his coat and wrapped it around her.

For the rain, he said.

Salt

Chicago salt is different.

You must taste it on the tip of your tongue as if you were Gandhi at the water, fist in the air.

I suppose some mythologies are perpetuated (man is the myth, myth is the man).

Just a teaspoon.

Unless you are in Chicago—then to taste.

Add extra spice as needed

Which spice is it that tastes like pepper and rain?

Lemons

Preheat the oven

I confess I have never started a fire and not cried.

I don’t have an arsonist’s way of chronicling history.

We came to embody love the way sailors are reluctant to love animals on dry land.

For the marinade

Plain yogurt

Some mythologies need to be fermented.

Do you remember who it was that said Jazz is African music played on European instruments?

Onions

While the onions are being chopped the children will sit at the feet of the eldest queer member of

the family for stories and laughter.

Garlic and ginger

Of course

Directions

Rub the lemon juice over and salt into all of your emotional wounds.

Save half for the chicken.

Set aside for 20 minutes.

Combine a tablespoon or so of the yogurt, the onion, garlic, ginger, and garam masala in a

blender or food processor and blend until smooth and pour it over the men.

Cover with saran wrap or aluminum foil and refrigerate for at least one generation, (but

preferably two).

Save half for the chicken.

Discard the lemon seeds.

Discard the leftover marinade.

Wait.

Remove from American made oven.

Go to the basement.

Carry the food.

Nail the door shut.

Sit down.

Hold hands in prayer.

Before you eat the rice, remember.

Remember looking at the hands of an elder and the hands of a child.

Remember the power in those hands.

I think about how my father held my hands

and showed me how to look at a sunrise with both eyes wide open.

Remember to breathe.

Serve with lemon or lime wedges.

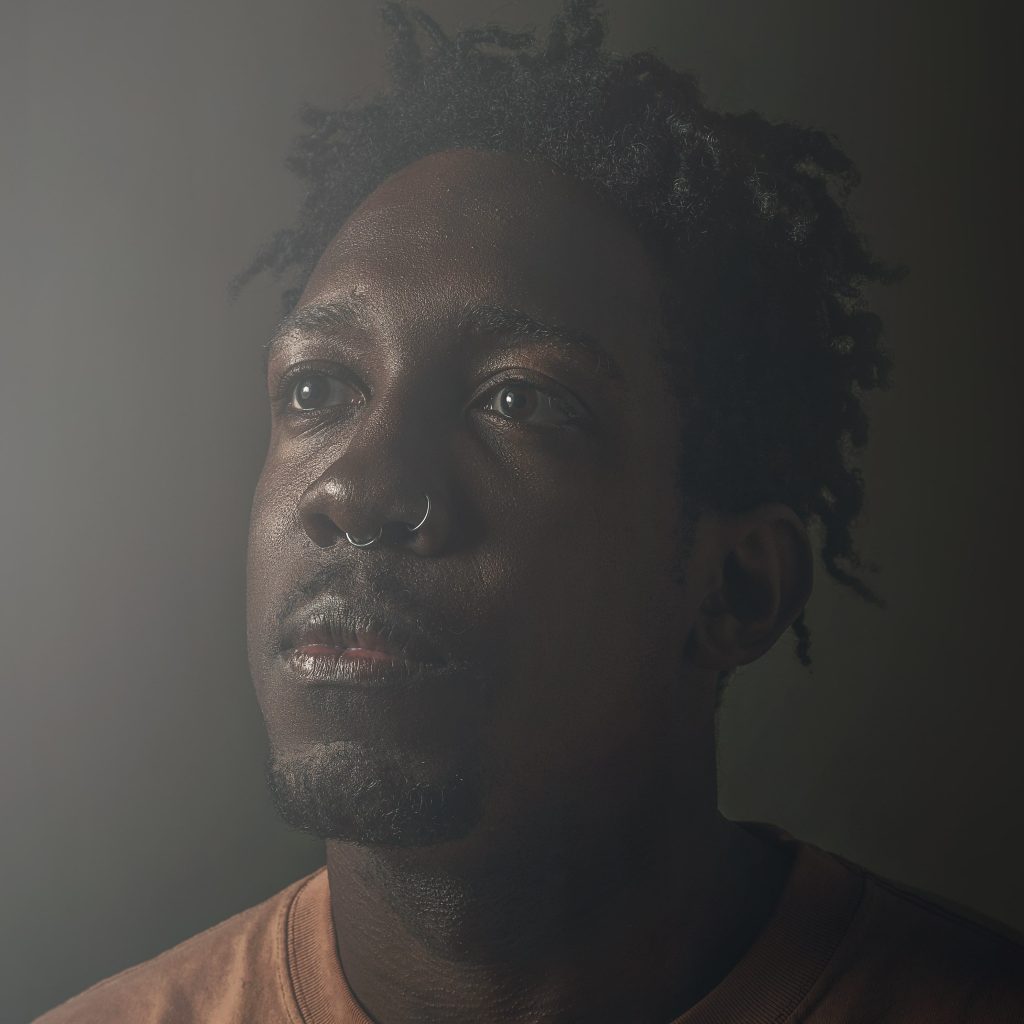

About the author: Hilesh Patel is a poet and member of the art group The Chicago ACT Collective (@thechicagoactcollective). He was born in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and has called Chicago home for most of his life. His work has been published in Relief Journal, Jaggery, AIOTB Magazine, and others. As a consultant, Hilesh works with nonprofits, small businesses, cooperatives, and collectives to guide and support strategic planning, infrastructure building, human resources, and leadership. He is also a mediator, facilitator, and teaches at the School of the Art Institute. You can find him on Instagram at @hilesh.

About the illustrator: NotaPlantShop (also known by his muggle name Damiane Nickles) is a painter and illustrator currently working out of Chicago, IL with roots in Brooklyn, NY. What started as a virtual plant shop selling potted plants with unique stories and running grassroots fundraisers for local organizations from his apt has since evolved into a creative practice that is not limited to one medium. From murals and painted ceramics to flat work and activations, Nickles continues to reinvent himself and bring credence to the chosen name NotaPlantShop. Regardless of which medium he works in, the focus is always on using form, color, and additive processes to explore communal memory and build community.