Featured image: An illustration of two pink figures wearing cat-like masks. One is tattooing the other. They are both in a red room with a model showing human anatomy in the background. Illustration by Sammi Crowley / @notcoolart.

Content warning: This essay recounts a personal experience regarding sex and trauma.

“Do you think it will be painful?” I already know the answer, but I ask anyway. I ask mostly because I’m acutely aware of how rigidly I’m lying on the leather chair, like a fresh corpse as rigor mortis onsets, and I want to distract myself by making conversation.

She sprays my bicep with isopropyl alcohol and uses a paper towel to wipe it dry. She starts at my shoulder and presses firmly down, repeating this motion several times. The alcohol’s stinging scent scalds my nostrils. She squints, inspecting the gleaming skin to make sure the stencil is completely transferred, and seemingly pleased, sets out three, small plastic cups, filling them with ink, one blue, one red, and one black. She prepares the tattoo gun, untangling the cord and testing the foot pedal to make sure it’s working properly. The gun itself looks like a thick index finger that’s been tightly wound in a black, fabric bandage. I avoid looking at the needle. This is not my first tattoo, but I joke to her that I always plan them with just enough time in between so that I forget the sensation. The first time Natallia tattooed me, I asked her how the tattoo gun works, and she indulged me, describing the different needles she uses in her thick Belarussian accent. This time I am afraid I’ll somehow spoil the ritual by acknowledging the blunt violence of it.

“This spot is usually less tender,” she explains and adds, “though, I have numbing spray if you need it.” Natallia adjusts the light on her work bench. “Alright, you ready?” I shake my head yes. She applies pressure to the foot pedal and the needle whirs, rising and falling in pitch like the faint buzzing of a mosquito hovering around your ear. As soon as the needle pierces my skin, I relax, recognizing the dull, persistent pain. I suppose I should have expected Natallia’s question. It’s the first thing everyone asks. It’s the first thing I’ve asked, putting friends, strangers and lovers in my crosshairs without pausing to consider that they may not have an answer. I didn’t have one when Natallia reclines in her rolling chair, holding the tattoo gun aloft like an open-ended threat, and poses the question to me, “What does it mean?”

As she presses the needle to my skin again, I think about all the times I’ve asked people this question, taking careful note of their response and thinking about how I might explain my own, and I remember asking Marco, an ex-lover, some variation of this question.

We were laying in his bed after sex, listening to Björk’s Vespertine and idly admiring each other’s bodies with post-coital raptness. I was taking inventory of his many tattoos. I lazily traced one on his abdomen with my finger, following the black panther’s lithe, exaggerated musculature as it stretched across his hip and ended just to the right of his mound of overgrown pubic hair. Except, where I expected to see a snarling feline head, I discovered the kittenish face of the animated character Betty Boop. Her wide, glossy eyes stared back at me, ringed by her triangular eyelashes like a child’s rudimentary drawing of the sun.

“How did I not notice this until now? You have to explain,” I insisted, suppressing laughter.

“Isn’t it obvious?” He took a deep breath and mimicked her affected, bubbly lilt, “Ain’t she cute. Boop-oop-a-doop. Sweet Betty.” I recognized the theme song from the animated shorts I used to watch as a child.

“Be serious,” I reprimanded, but he shook his head and pretended to zip his lips shut. He kissed me softly on my forehead, as if to chase the question from my head, but I persisted. I shimmied up on my elbows so I could look into his dark eyes. I pouted. “Please.”

“Don’t you think I could be Popeye?” He asked and furrowed his brow, flexing both of his biceps. I squeezed them and clucked my tongue, pretending to be unimpressed. I tried to think of one of Popeye’s iconic lines to quote back to him, but all I could remember is that his character eats spinach to gather his strength and rescue his girlfriend.

“You do have that same kind of rough-around-the-edges masculinity he does,” I said and rubbed his shaved head idly. He grinned at me, wrapping his arms around me and squeezing tightly, as if he thought I might be mocking him and needed to demonstrate his bearish strength. “Doesn’t Popeye cheat on his girlfriend with Betty Boop though?”

“What? Is that true?” He looked at me quizzically and relaxed his grip. He spoke slowly and deliberately, which emphasized his husky, smoker’s voice, and often waited so long before responding to a question that I worried he may not have heard me and asked the question again. “I always thought they were boyfriend and girlfriend.”

“No, I think his girlfriend was the other girl—the scrawny one that Shelley Duvall played in the live-action film. I’m not sure though. My knowledge of the Popeye universe is pretty minimal. We’d have to google it.” I looked around for my phone but didn’t see it anywhere in reach. His room was too dim, illuminated red and purple by two small orbs. It was probably in my tote bag somewhere on his bedroom floor. “But I don’t feel like getting up. I’m too comfortable, so you should tell me what it means. C’mon. I won’t make out with you again if you don’t tell me.”

“Is that so?” He asked and leaned in to kiss me, but I pulled away abruptly. The Björk album had stopped playing, leaving us with just the soft hiss of the record needle trailing along the vinyl. He stared at me, breathing softly. I could smell the musky, pungent scent of sex on his breath like the thick, yeasty scent of beer. I felt myself getting lightheaded, staring fixedly at his mouth, but I managed to shake my head. Yes, it is so.

“So, you really want to know what it means that bad. You’re gonna be disappointed.” He rolled his eyes. I inspected his face with interest as if I might find some sort of logical framework hidden in his doe-like eyes that would disclose some primal aspect of his character and allow me to understand him in perpetuity. I found nothing. “Well, the artist offered to give me a tattoo for free if he could do any design that he wanted, and I figured, ‘Why not? It’s a free tattoo.’ And that’s the full story.”

“Hmm.” I scrutinized his tattoo again as though I expected it to suddenly transform or reveal some new, hidden meaning. Except, Betty Boop’s expression remained playfully provocative and slightly eerie as though she was a cat that we forgot to shut out of the room who was now watching our intimate moment with mild disinterest. I broke eye contact and leaned down to kiss Betty Boop’s face before moving upward, kissing his neck for a moment and trailing my tongue along one of his protruding veins. I followed the vein to the base of his ear and whispered, “You know what you said earlier at dinner about there being no such thing as a bad tattoo. I’m starting to think you might be wrong.” I was deadly serious.

He gasped and flopped his head on the pillow, making a pained expression and clutching at his heart. “Ouch, you didn’t need to bring out your claws,” he accused and jabbed me in my ribs with his index and middle finger, “you’re such a brat.”

I laughed and kissed him again. We fucked for the second time that night. But, when he smacked my ass this time, he did not hesitate or slow the momentum of his hand before striking me out of fear that he might hurt me. I bit my own arm to avoid yelling out, worried that his roommates might hear. Afterwards, I put on my underwear and crept to the bathroom. I admired the crimson handprints imprinted in my skin as they slowly faded like fall leaves slowly losing their vibrant color before dropping to the earth.

What does it mean? This same question I doggedly asked Marco, Natallia poses to me while holding me at somewhat literal gunpoint. She had already begun tattooing when she asked me the question. She started at the center of the image, working her way outwards, carefully tracing the countless arched lines like a farmer meticulously tilling his fields. A pile of paper towels blotted with blood and ink accumulates on her worktable. It is too late. I can’t decide that I don’t want the design if she passes a similar judgment on my selection, so I anxiously try to think of an explanation that will make the tattoo sound more intentional and profound.

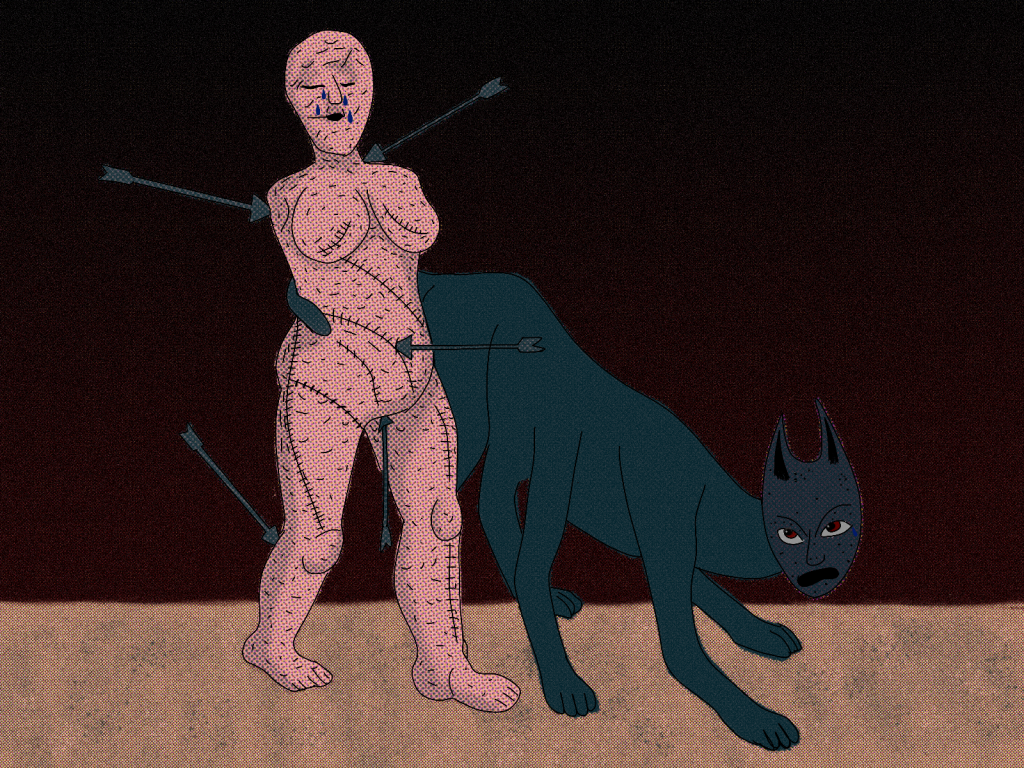

“It’s a drawing by the French artist Louise Bourgeois. It’s her interpretation of Saint Sebastian, who was martyred by a Roman emperor. I think in the story they shot him with 13 arrows.” Natallia inspects the tattoo stencil with her gloved fingers like a dermatologist fiercely scrutinizing a constellation of moles. She counts quietly under her breath. The sun beams through her studio’s western facing windows. Sweat beads on my forehead. She delivers her diagnosis.

“There’s only nine arrows.”

“Oh. Maybe it was nine,” I reply, feeling a rush of heat in my cheeks.

For a moment, I consider leaving, allowing her to continue tattooing until she sets the gun gingerly on her cart, stretches her arms above her head, and steps out of the studio to take a bathroom break. I would slip out of her studio undetected. I scheduled the appointment out of a sense of urgency. Natallia posted to Instagram that she was moving to Los Angeles at the end of the month, and I was determined to have her tattoo me again. I vaguely knew that I wanted a drawing by Louise Bourgeois, but I didn’t know which one, so I scrolled through every Bourgeois work available through MOMA’s online database—all 3,039 of them—before deciding on Sainte Sébastienne (1992).

I loved the shape of the figure, the way Bourgeois stretched breasts, hips and stomach, exaggerating these features the way a pubescent teenager does when they absentmindedly draw the female form in the margins of their notebook. I loved Bourgeois’ use of thin, organic lines to emphasize the meatiness of the body, the dragging weight of the breasts and the column-like strength of the thighs. I loved that the figure was headless. I loved the volley of arrows piercing the body and the delicate wounds wherever they struck the figure, rendered in blood red ink. I loved the drawing, but I knew nothing about it when I decided to inscribe it on my body.

“You said she’s a French artist?” Natallia asked, pressing the needle more firmly as she shaded one of the red wounds. I winced.

“Well, she was born in France, but she moved to New York after she married an American art historian. Her family owned a tapestry restoration business and she used to help repair the tapestries as a child, which is how she developed an interest in art.”

Tapestry making was Louise Bourgeois’ family tradition, their family business. Bourgeois’ mother, Joséphine, and grandmother, Henrietta, both spent their childhoods in Aubusson, a town in Central France founded by tapestry makers in the sixteenth century. Henrietta owned her own tapestry making atelier. Her eldest and most cherished son, Alex, was the atelier’s dessinateur (draftsman), making the drawings from which the tapestries would be made, while Joséphine helped with the dyeing and reparation of tapestries. Joséphine met Louis Bourgeois through her brother Emile. Louis and Emile both shared an interest in gliding and often invited Joséphine to accompany them as they rode their bikes to the flying fields. Emile teased Louis for pursuing his sister, calling him a kid and insisting that he shouldn’t court Joséphine, who was five years older than him.

But Joséphine loved Louis. The pair eloped in 1905 and had a daughter, who died shortly after birth. They had a second daughter, Henriette, and, on Christmas Day in 1911, they had their third daughter—Louise. Joséphine was embarrassed that she had produced three daughters, feeling that she was depriving her husband of a son, despite being a feminist. Yet, she cleverly insisted, “Don’t you see, this little girl, we are going to name her for you. Do you know that that child is your spitting image?” Their resemblance haunted Louise as she got older. She felt that her mother only loved her because she was handsome like her father and that she had to create ways of making herself likeable and useful to avoid being abandoned by her mother. Two years after Louise is born, her parents finally have a son.

When she was eight years old, Louise found a way to make herself useful and was employed in her grandmother’s Aubusson atelier to help her uncle as a dessinateur because there was so much work. This was highly unusual. Women were typically forbidden from working as draftsmen. But she was privileged as the owner’s granddaughter and started filling in on Thursdays and Sundays. She was only allowed to draw feet and legs when she first started and quickly became an expert at rendering these limbs.

In 1919, her parents purchased property in Choisy-le-Roi, a suburb of Paris, where they ran their own atelier for tapestry repair. Shortly after World War I, Joséphine and Louis hired a British au pair, Sadie Gordon Richmond, to teach their children English. She lived with their family for almost a decade and started sleeping with Louis, a fact that Joséphine willfully ignored to Louise’s bewilderment. Louise felt betrayed, betrayed by her father, who found another woman and introduced her to his children, breaking unspoken rules of family life; betrayed by her mother, who tolerated her husband’s infidelity and used Louise to keep track of him; and betrayed by Sadie, who was hired as Louise’s teacher and instead competed with Louise for her father’s attention. She reacted most violently towards her father’s betrayal, but she harbored resentment for Sadie her entire life. Bourgeois admitted that she dreamt of getting rid of her father’s mistress by twisting her neck, like wringing out a freshly washed tapestry, waiting for her neck to turn a dull shade of charcoal. Nearly 70 years after these events, Bourgeois contemptuously pointed out Sadie while describing a photograph of her family at Sunday brunch, deriding her for wearing all white—which she considered a bid for attention—and said, “You see that pussycat face on the right? …I’m right next to her.”

Anthropomorphized cats and people morphing into cats become a recurrent visual motif throughout Bourgeois’ career. While living with her husband and three sons in an 18th Street apartment in New York City during the 1950s, Bourgeois had two cats: Tyger and Champfleurette. The name Champfleurette was a joke, a feminization of the French writer and art critic Jules Champfleury, who authored “Les Chats,” a book of essays on cats with illustrations by artists such as Manet and Delacroix. Bourgeois used Champfleurette as a model for her drawing Champfleurette, the White Cat (1994). In the drawing, the cat sprawls languorously in an empty room. Her body is exaggerated and elongated. She kneels in a pair of heels, propping up her bulging rump, and holds her tail slightly aloft so that her dainty pussy is tantalizingly noticeable, like a keyhole through which movement in a separate room can be seen, tempting you to press your eye to the opening out of an insatiable curiosity to know what is happening beyond. The domestic cat broadcasts her sexual desire and becomes promiscuous, perverting the home. Champfleurette being a white cat is important. Louise Bourgeois loathed that Sadie often wore all white because she saw it as a desperate plea for attention and frequently used the color in order to allude to the mistress in her artwork. Perhaps this drawing represents Sadie’s betrayal, the self-interest of an interloper who embeds themselves within the family, which Bourgeois never forgot. And which she never forgave.

Coincidentally, Bourgeois depicts herself as becoming cat-like in an earlier version of Sainte Sébastienne completed in 1987. This was not the first time Bourgeois used Saint Sebastian as a subject. These later drawings reference an earlier, more abstract of the same title from 1947. She habitually fixated on various subjects, making drawings and sketches obsessively for several years until she exhausted herself and abandoned the idea. Yet, her obsession often reappeared years later with renewed fervor. And, forty years after her initial drawing, Bourgeois portrayed herself as a feminized version of the third-century Christian martyr again, running naked and armless as she is struck by a volley of arrows.

Except, she is not headless in this version. Her long hair streaks behind her and a cat’s face emerges faintly from beneath Bourgeois’ own; Her mouth doubles as the cat’s second eye. The image is like an inversion of Marco’s tattoo. Instead of Betty Boop’s head appearing on a prowling jaguar, a cat’s face is transmogrified onto Bourgeois’ hyper-feminized body. When asked to describe Sainte Sébastienne, Bourgeois explains, “This is a self-portrait of a person who is very happy and running and then suddenly realizes that she has antagonized certain people. She gets shot at. Then she is transformed from a nice, sweet creature into a mean, feline person… It’s a state of being under attack, of being anxious and afraid. What does a person do when they are under siege? You better understand why you are being attacked. Is it provoked? Is it revenge? Do you fight back, or do you run for cover and retreat into the protection of your own lair? That is the big question.”

Bourgeois was interested in transparency. She wanted to be transparent in her art. She felt that if people could see through her, they could not help loving her, forgiving her. As she got older, she felt that the problems she was interested in solving through her artwork were directed toward other people rather than toward ideas or objects. She thought fulfillment would come from communicating with another person. She made art as an attempt to communicate an intense experience. And she repeatedly felt that she had failed to do so.

For one of her more well-known sculptures The Destruction of the Father (1974), Bourgeois cast hunks of mutton and beef in plaster, later coating them with latex rubber, and placed the inedible, dismembered shapes on a table surrounded by breast-like bumps and phallic protuberances. She lit the womb-like installation with crimson lights. The artwork represented a childhood fantasy of Bourgeois where she and her family, tired of hearing their father boast and talk about himself, throw him onto the dinner table and cannibalize him. She wanted to purge this fear of her father, his authority, his betrayal, through violence. Bourgeois was relieved that she was able to expunge her aggression and confine it within her art.

I first discovered this sculpture by Bourgeois while reading Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father, a collection of the artist’s writings and interviews that I borrowed from my university’s library. I was taking meticulous notes in a marbled notebook that I bought from Walgreens with the idea of writing an essay about Bourgeois’ sweet tooth and her lifelong depressive episodes that never actually progressed beyond a list of bulleted quotations. Coincidentally, I was reading this book the summer Marco and I met and brought it with me everywhere, including to Hollywood Beach, where we had agreed to meet for a date one scorching August afternoon. I arrived early and laid my cheap polyester towel on the sand far from where the crowd congregated along the water’s edge, immersing myself in the book to pass time.

Occasionally, I set the book aside, carelessly resting it upside down in the sand, and observed the beachgoers. I watched a pair of older men sunbathing in pink neon thongs whose generous application of suntan lotion made them gleam like freshly polished bronze statues. One of them slowly flipped over onto his stomach like an overturned beetle righting itself. I returned to my book. I transcribed a 1973 entry from Bourgeois’ diary into my composition journal, carefully dating and noting the page number for when I eventually had to surrender the book: “I did not deserve to be loved so that I turned people against me. I did not deserve to be lovable, to be lovable means to be killed, to be fucked means to be killed.” Underneath this quote, I wrote a question, Do I deserve to be loved? Have I turned people against me?

I was so absorbed in my note taking that I didn’t notice the man approach until he was standing directly above me. I looked up expectantly, using my hand to block the sun’s glare. I expected it to be Marco, so I was shocked when I realized it was a middle-aged man. He was wearing an eggplant-colored long-sleeved shirt, a pair of black trousers, and monogram loafers. Most noticeably, he had a gaudy, crystal encrusted watch on his wrist that caught the sun and cast small rainbow prisms in every direction. He grinned at me with a mouthful of teeth as yellow as gouda cheese and said, “You are so beautiful.”

“Thank you.” I smiled politely and racked my brain, trying to figure out why he looked so familiar.

“What are you reading?” He asked.

“A book about the artist Louise Bourgeois.”

“Wow, so you’re beautiful and appreciate art. That’s so rare. Can I tell you something? I’m actually a gallery owner and, well, I just have to ask, have you ever considered selling art?” He spoke quickly, yet deliberately, like a well-rehearsed street fundraiser appealing to your sense of guilt while physically edging closer, blocking your path. I tried to look around surreptitiously to see if Marco was approaching. He continued talking, “What do you do for work? Can I ask—How much are they paying you? I can guarantee you its pennies compared to what I would pay you. Pull out your phone. No seriously. Pull out your phone. I want you to google something. Lookup ‘African Masterpieces.’ The first image that comes up is one of mine.”

I suddenly remembered why he seemed so familiar. He had dictated these instructions almost verbatim a few years earlier while sitting next me on the 147 Bus. He approached me while I was waiting for the bus. I had just finished a shift at my fast-food job and smelled vaguely of stale bread and anchovies. He complimented me and launched into his pitch, telling me about his gallery in Rogers Park. I nodded my head attentively to reassure him that I was listening closely. After two years of living in the city, I had grown used to such encounters. I figured I only had to entertain him until the bus arrived, but, when he followed me onto the bus and urged me to sit beside him, I became nervous. He insisted that I google “African Masterpieces.” When I didn’t immediately follow his instructions, he repeated himself more forcefully, “Take out your phone.” I did. When the search results came up, he pointed to the first image, a black marble bust of an African woman wearing a traditional headdress. “I own that.”

“Oh, wow, that’s beautiful,” I offered and made brief eye contact with the older woman who was sitting across from us and listening to our conversation with a curious expression. She quickly averted her gaze, returning to her phone.

He showed me his watch and implored, “Isn’t it beautiful? I bet you wish you had something this nice. You could afford something like this if you worked for me.”

“I don’t really wear watches.” I shrugged my shoulders and stood up, preparing to get off the bus.

He stood up with me, and I felt my pulse quicken, thumping loudly in my neck. He offered me a ride, telling me that his car was parked just down the street. He wanted to show me his gallery and take me for a ride in his luxury car, a make and model that meant nothing to me. I pretended to consider and invented a boyfriend, explaining that he was waiting for me. The man insisted, “We’ll only be there for a few minutes. Your boyfriend can’t wait?” I expanded the lie, adding that we had plans to meet other friends for dinner and therefore increasing the number of people who might find my absence worrisome. He gave me an exasperated look and sighed. I declined his offer several more times. Eventually, he surrendered and offered me his business card, which I politely pocketed. I walked past my apartment building and sat in a nearby café for a while before returning home.

Years after this incident, I couldn’t believe that he was standing above me. If he recognized me, he didn’t acknowledge it. But I recognized him.

He repeated himself. “C’mon, baby. Get your phone out of your bag and look up ‘African Masterpieces.’” I didn’t move. I confessed that I remembered him from before and explained that I already had a job in the arts, I wasn’t interested in working for him.

His mischievous smile faded and was replaced by a stony expression. “So, you think that you are hot shit now? Well, let me tell you something. I’m an important person in the art world and you? You’re a nobody and you’ll always be a nobody.” His voice coarsened and I felt increasingly aware of the fact that I was essentially naked as he loomed threateningly above me.

“Okay.” I replied. I wanted to call him delusional, explaining that I was intimately familiar with Chicago’s gallery owners and wealthy art patrons after years of working with them, but I restrained myself.

He scowled and stepped closer to me, kicking a small cloud of sand onto my towel. I swept it off perfunctorily. Marco arrived at this moment, rolling up with his bike. He greeted us both with a sheepish wave and looked expectantly between us, raising his thick eyebrows in confusion. I imagine he must have been trying to understand the exchange he interrupted as the man’s eyes darted aggressively between Marco and me. He asked us both, “How are you doing?”

The man stepped backwards as Marco approached, his presence becoming less menacing, but his face continued to curdle like souring milk, becoming misshapen and mottled. He didn’t look at Marco. “You’re disgusting. What are those spots on your skin? You look like you have herpes. You’re filthy. Fuckin’ fairy.” He spoke viciously, pointing at the small spots of discoloration dotting my chest and inner thighs.

“Okay.” I repeated, trying to end the encounter as quickly as possible. Without warning, the man spit on me, sucking in his cheeks like a hunter pulling back the string of their bow before launching a large glob of gravy-colored spittle at me. It landed on my stomach. He trudged off, muttering insults that I couldn’t hear over the ringing in my ears. I refused to look at Marco and hurriedly wiped the spit off with my hand, rubbing it into the rough fibers of my towel. I was shocked at how warm the spit was. It left a shiny wet streak. My hands were trembling uncontrollably, so I sat up and squeezed them between my thighs. Marco set his bike gingerly on the sand and flopped down next to me.

“Did you know him?” he asked. I shook my head.

“It’s not herpes,” I said dumbly. “It’s a harmless fungal infection. I’ve tried using that medicated soap that’s supposed to help, but it smelled like rotten eggs and didn’t really work.”

Marco gave me a sympathetic look and nodded as if to say that he understood. I felt lightheaded, like my head was a pot of water that had just started to boil, vibrating from the steady stream of air bubbles. Marco unbuttoned his shirt and dug a bottle of sunscreen out of his backpack. “Do you mind helping me put sunscreen on my back?” He had an egregious farmer’s tan. His torso was several shades lighter than his forearms and neck. I took the bottle and squirted a generous amount of sunscreen into the hand I had just used to wipe up the spit and pressed it to his furry back. I rubbed the sunscreen in wide circles.

I couldn’t believe that Marco was reacting so calmly. Had that really happened, or did I imagine it? How much of the conversation had Marco heard? Why didn’t he ask me if I was okay at the very least? Was he nervous to confront the man and draw attention to himself in front of all the beachgoers? He had already been a little skittish when we agreed to meet at the gay beach; I was the first trans person he had ever dated, a fact he confessed after the first time we had sex. Did he think that by acknowledging my shame and embarrassment he would somehow be contaminated by them? Did he subconsciously agree with the man’s judgement and was pretending otherwise as long as I continued to fuck him? My head was pounding, and my vision had gone blurry. I had a sudden fantasy of jumping up, wrapping my hands around Marco’s neck and squeezing with every ounce of force that I could muster, feeling the blunt edges of my fingernails break through the thin layer of skin, while screaming, “What the fuck is wrong with you? Do you not care about me at all?”

Instead, I asked him about his day. He complained about his job at a small tech start-up. He was irritated with his boss, who was pressuring him over some deadline, and fantasized about quitting his job, finally pursuing work he was passionate about. I waited for him to finish his rant, listening disinterestedly. I didn’t retain any of his story’s important details. He looked at me expectantly when he finally stopped talking. I replied dryly, “I don’t know. Why don’t you just quit now if you hate it so much? You can’t blame him for caring just because you don’t.”

“That’s not how the world works, Riley.” He snapped, and I felt his shoulders tense underneath my hands. I told him that I was done, wiped my palms off on my thighs and laid back down on my towel. He laid beside me and pulled his own book out of his backpack. He placed one of his hands on my thigh in a silent gesture as we sunbathed. Occasionally, he read a line from his book aloud, enunciating each word carefully like a spoken word poet. I pretended to read. I held my book above my face and let my eyes wander across the words, absorbing the faint blur of printed ink shapes until I reached the end of the page and flipped to the next one, repeating the mechanical action.

We decided to go back to my apartment after an hour. I rode on the pegs of his bike with my arms wrapped around his waist and pressed my hand against his hip where I knew his Betty Boop tattoo was beneath the thin layer of fabric. He suggested that we should take a shower. I agreed. I offered that he could wash himself first, but he placed his hand underneath the stream of water and winced, moaning that it was too hot. I laughed at him and made a show of luxuriating underneath the scalding spray. He rolled his eyes and offered to rub me down with soap. He started with my chest before motioning me to turn around. I obeyed. He massaged the soap gently into my shoulders and worked his way towards my ass. He cupped it with both hands and growled like an overenthusiastic porn star, which made me laugh.

“You like?”

“Yes,” he muttered and gently gripped my hips, applying pressure until I allowed my back to arch. I leaned forward further, pressing my head against the cool tile of the shower wall.

He murmured, “God… Can I fuck you like this?”

I nodded without opening my eyes. I braced myself. His cock was shaped like a baseball bat, thinner at the base and tapering to a wide, blunt head. He stood bowlegged for stability and eased himself inside. I gasped. He thrust several times before he accidentally slipped out. He struggled to reinsert himself. He was several inches shorter than me, which made the angle difficult. He put one of his feet on the edge of the tub and angled himself, sliding back inside. I winced and tried to position myself better, arching my back until I felt my spine grow tense, like an elastic band being pulled part, growing thin and white just before it snaps. He continued to fuck me. He grunted, seemingly struggling. I placed my left forearm on the wall and allowed the weight of my upper body to press against the wall. My feet slid backwards across the porcelain, squealing faintly, pushing him further into my ass. I put my fist in my mouth to stifle the sounds emanating from me. I wanted him to cum so that the moment would end. But I also needed the affirmation of his desire for my body more than anything in that moment as evidence that the man was wrong; I am not disgusting. I am wanted. I felt as though I was watching the scene unfold from the sidelines. I imagined myself as Champfleurette, my rotund rump raised in the air, my brazen cunt like a small split seam and Marco couldn’t resist the urge to tug at the loose thread, widening the injury until it became a gaping, irreparable gash.

“Stop.” I said and pushed on his hips, forcing him out of me. He moaned, his cock bouncing mercilessly.

“Does it hurt?”

“Yes.”

“Do you want to try a different position?”

“No, I don’t think I can.”

“Okay, do you mind if I finish?”

I said sure and rested my head against the wall again, listening as he finished himself with a grunt and came all over my back. I climbed out of the shower and used a wad of toilet paper to wipe myself off. His cum was the same shade as the man’s spit. I dropped it unceremoniously into the toilet and flushed it. Marco dried himself off, kissed the nape of my neck and asked, “That was so hot. Do you want to order some food?”

“No, I’m actually pretty tired. I think you should probably go home.”

“Oh, okay.” He got dressed slowly and I watched with folded arms as he double-checked to make sure that everything was inside his backpack. “I had a nice time today,” he said and kissed me. I barely responded, refusing to unfold my arms. He left. I closed the door behind him and waited until I heard his footsteps fade and the front door slam to turn the deadbolt. It clicked shut with a finality that made me feel a wave of exhaustion. I sat on the couch and stared at the opposite wall, watching as the sunlight waned and my apartment grew darker. Eventually, I stood up and turned on the living room light and unpacked my tote bag. I took my beach towel out to the back porch and briskly shook out the sand. An opaque cloud of dust drifted through the alley. As I folded the towel, my hand grazed the dried crust of his spit, which had mixed with the fine sand. I balked and felt a sudden wave of nausea. I descended the three flights of stairs and tucked the towel neatly into the dumpster, stuffing it between two distended trash bags.

I trudged back upstairs. I saw that I had a text from Marco. “Hey, I just wanted to say again that I had a nice time tonight. I couldn’t tell for sure, but you seemed a little upset when I left. If I did anything wrong, I’m sorry.” I dropped my phone on my kitchen table and paced around the living room. I straightened the books on the coffee table and returned to my phone. I started to draft a response and deleted it, making several other attempts, all of which I ended up deleting. I felt an overwhelming sense of failure, an inability to communicate the complex web of emotions I was feeling, so I left my phone on the kitchen table and went to bed. I never replied, and we never saw each other again.

Recently, during a skin cancer screening, I stripped off my clothes, folded them on the chair next to me and changed into a mint green paper gown. The dermatologist knocked on the door and I told her to come in. She asked me to sit on the examination chair and gingerly lifted the sleeve of the paper gown, noticing my Sainte Sébastienne tattoo. She ran her gloved fingers over the inked skin to check for irregular texture. “The linework is so fine,” she remarked and asked, “What does it mean?”

I responded without pause, “It represents pain.”

Acknowledgment

Thank you, Dad, for always reminding me that cracking a joke can be the most powerful remedy when life feels ugly and for teaching me the value of a good story. I love you to the moon and back.

Links

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/destruction-father-reconstruction-father

https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/42/675

Riley James Yaxley (they/them) is a writer, poet, and fundraiser based in Chicago, Illinois, living on unceded land of the Kickapoo, Peoria, Potawatomi, Miami, and Očhéthi Šakówiŋ peoples. They hold a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Writing, Rhetoric, and Discourse from DePaul University, specializing in professional writing and queer and feminist rhetorical histories. Riley started their career working at a number of arts organizations in Chicago, including Chicago Gallery News, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Wrightwood 659, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Riley is a regular contributor to Chicago Gallery News and ADF Web Magazine, aiming to uplift BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists and challenge systems of inequity within the art world through their writing.